Congenital Zika Syndrome

Background

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a flavivirus (family Flaviviridae), an RNA virus primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. These mosquitoes generally bite during the day, with peak times in the morning and early evening. These mosquitoes also transmit dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever viruses. Transplacental (vertical) and sexual transmission of the virus have been documented, as well as transmission by blood transfusion. Although Zika virus has been recovered in human milk, transmission through breastfeeding has not been definitively demonstrated.

Main clinical manifestations in the mother

The risk of a pregnant woman acquiring a primary infection is the same as that of other adults. Symptoms of ZIKV infection are generally mild, non-specific and self-limited, lasting two to seven days. Symptoms vary and might include maculopapular rash, low-grade fever, conjunctivitis, muscle and joint pain, arthritis, malaise and headache. However, a large percentage of infections are asymptomatic.

The most concerning feature of ZIKV infection is maternal infection during pregnancy that poses a risk of congenital ZIKV and resultant birth defects in the fetus. ZIKV infection should be suspected based upon symptoms and exposure (residence in or travel to an area with active ZIKV transmission) or sexual contact with a person who has been exposed, with confirmatory laboratory testing whenever possible.

Main clinical manifestations in the infant

Congenital ZIKV infection can lead to a spectrum of birth defects. Severe manifestations can result in a recognized pattern of birth defects known as CZS. Although many of the components of this syndrome – such as cognitive, sensory and motor disabilities – are shared by other congenital infections, there are five features that are rarely seen with other congenital syndromes or are unique to congenital ZIKV infection:

- severe microcephaly with partially collapsed skull and redundant scalp with rugae (extra skin folds);

- thin cerebral cortices with subcortical calcifications;

- macular scarring and focal pigmentary retinal mottling;

- congenital contractures of major joints (arthrogryposis)*; and

- marked early hypertonia or spasticity and symptoms of extrapyramidal involvement*.

* Noted in infants with structural brain anomalies only.

Since initial clinical descriptions were published, three additional features that appear to be unique to congenital infection with ZIKV compared with other established STORCH infections include paralysis of the diaphragm, neurogenic bladder and hypertensive hydrocephalus following severe microcephaly.

Other anomalies that are commonly reported with congenital ZIKV infection can be seen with congenital CMV but less so with other congenital infections, including cortical atrophy, corpus callosal agenesis/hypoplasia, cerebellar (or cerebellar vermis) hypoplasia, neuronal migration defects such as gyral anomalies or heterotopia, periventricular calcifications, hydrocephalus ex vacuo, glaucoma, and postnatal-onset microcephaly. Additional anomalies that are common to a number of congenital infections (including CZS) are microcephaly, hydrocephaly/ventriculomegaly/colpocephaly, calcifications of basal ganglia or unspecified regions, hearing loss, porencephaly, hydranencephaly, microphthalmia/anophthalmia, optic nerve hypoplasia, coloboma, and cataracts – these anomalies cannot reliably be used to differentiate among congenital infections.

Primary ZIKV infection during the first and early-second trimesters of pregnancy is more commonly reported in infants with more adverse outcomes. Infection in the third trimester is associated with less severe defects of the brain and eyes. Milder cognitive effects such as learning disabilities have also been reported but are not yet linked to a specific trimester of exposure. Congenital ZIKV infection has been associated with other adverse birth outcomes such as miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death.

Fig.56. Clinical findings in the infant

Lateral views showing collapse of the cranium and extreme reduction in height of the cranial vault.

Photograph source: Moore et al., 2017; Ritter et al., 2017

Posterior scalp view showing redundant scalp with folds (rugae).

Photograph source: Moore et al., 2017.

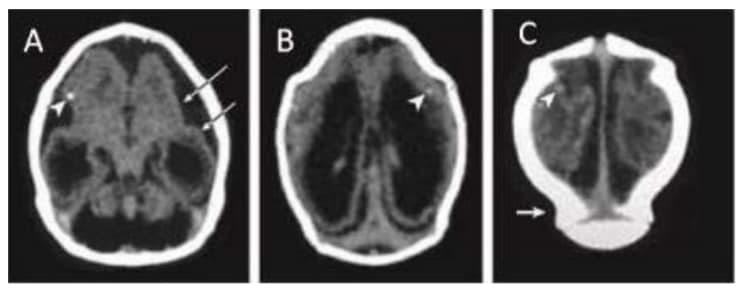

Computed tomographic (CT) scan in one infant with prenatal ZIKV exposure shows scattered punctate calcifications (A, B and C; white arrowheads), striking volume loss shown by enlarged extra-axial space and ventriculomegaly (A, B and C), poor gyral development with few and shallow sulci (A; long white arrows). The occipital “shelf” caused by skull collapse (C; white arrow).

Photograph source: Moore et al., 2017 .

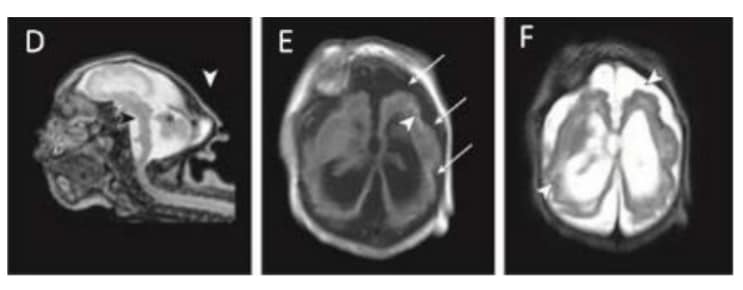

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in infant with prenatal Zika exposure shows scattered punctate calcifications (E; white arrowheads), very low forehead and small cranial vault (D), striking volume loss shown by enlarged extra- axial space and ventriculomegaly (D, E and F), poor gyral development with few and shallow sulci (E; long white arrows), poor gyral development with irregular “beaded” cortex most consistent with polymicrogyria (F; white arrowheads), flattened pons and small cerebellum (D; black arrowhead and asterisk). The occipital “shelf” caused by skull collapse is seen in both infants (D; white arrowhead).

Photograph source: Moore et al., 2017.

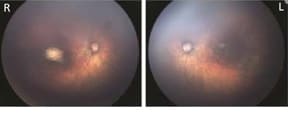

Fundus images of right and left eye: Optic nerve hypoplasia with the double-ring sign, gross pigmentary mottling, and chorioretinal scar in the macular region.

Photograph source: Moore et al., 2017; Ritter et al., 2017

Left: Newborn infant with bilateral contractures of the hips and knees, bilateral talipes calcaneovalgus, and anterior dislocation of the knees. Right: Newborn infant with bilateral contractures of the shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and right talipes equinovarus. Hips are bilaterally dislocated in both infants.

Photograph source: Moore et al., 2017 .

Relevant ICD-10 codes

P35.8 Other congenital viral diseases

Q02 Microcephaly

Checklist

| Checklist |

|