4.10 Abdominal wall defects

Omphalocele

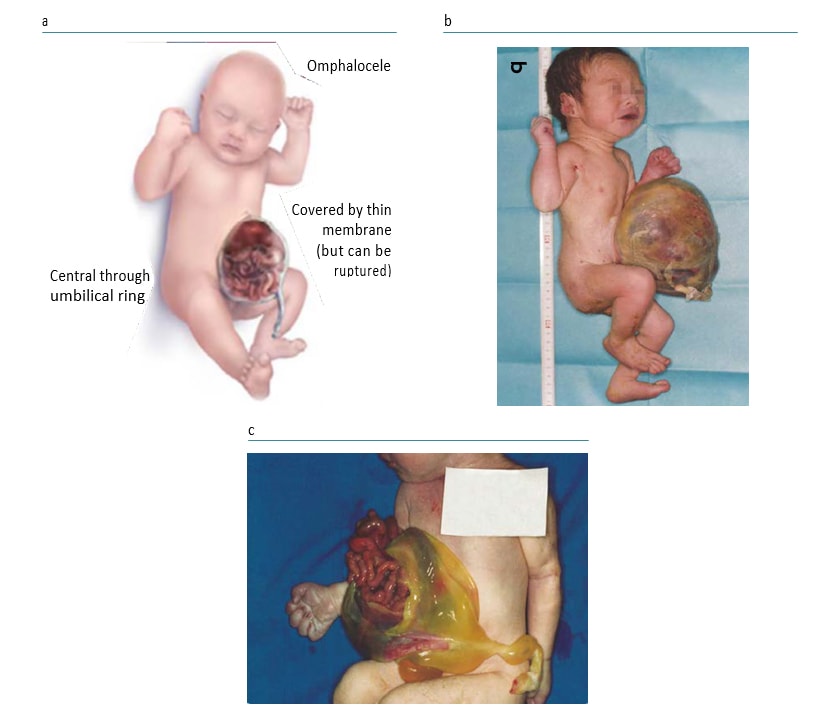

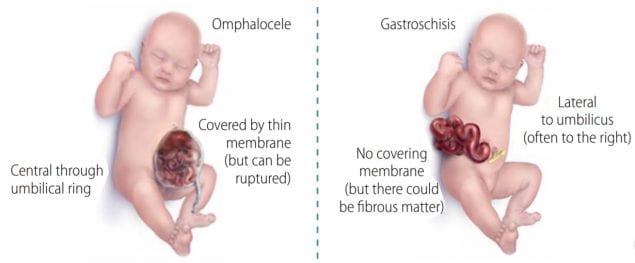

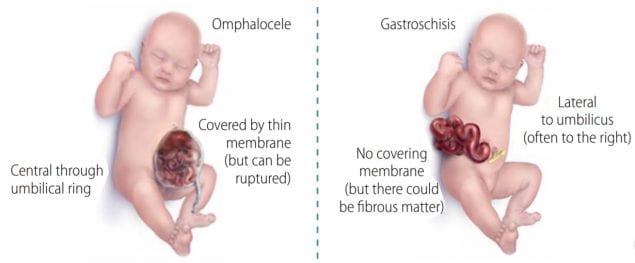

Omphalocele or exomphalos is a birth defect of the central portion of the anterior abdomen in which the herniated organs (intestines and sometimes other abdominal organs such as liver) are covered by a thin membrane (Fig. 4.42, panels a, b). At times, the membrane – which consists of the peritoneum and amnion – might be ruptured (panel c) or matted. The key finding in omphalocele is that the herniation occurs centrally – the organs herniate through an enlarged umbilical ring, with the umbilical cord inserting in the distal part of the membrane covering the defect (panels a, b). This presentation is in contrast to what is seen in gastroschisis, in which the abdominal defect is lateral to the umbilical cord and herniated organs are never covered by membrane.

Fig. 4.42. Omphalocele (Exomphalos)

Photograph source: CDC–Beijing Medical University collaborative project.

Relevant ICD-10 codes

Q79.2 Omphalocele (exomphalos)

Note: Avoid using the generic Q79 code for congenital malformations of the musculoskeletal system not elsewhere classified. This generic code includes other anomalies that must be distinguished from omphalocele.

Diagnosis

Prenatal. Omphalocele might be diagnosed prenatally and distinguished from gastroschisis, but it can be missed and the distinction from gastroschisis is difficult and error-prone. For this reason, a prenatal diagnosis should always be confirmed postnatally.

When this is not possible (e.g. termination of pregnancy or unexamined fetal death), the programme should have criteria in place to determine whether to accept or not accept a case based solely on prenatal data.

Postnatal. Careful examination of the newborn can confirm the diagnosis of omphalocele and help distinguish omphalocele from gastroschisis as well as from several rarer similar phenotypes (e.g. limb-body wall defects). Typically the membrane covering an omphalocele is thin and translucent, but at times this membrane will rupture during or shortly after birth and the surface of the membrane might appear matted and covered by fibrous material as a result of prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid in utero.

Clinical and epidemiologic notes

Distinguishing omphalocele from gastroschisis is important because these conditions have different causes, associated anomalies, approaches to treatments and outcomes.

On the mild end of the spectrum, omphalocele can be occasionally confused with umbilical hernia. To differentiate, an umbilical hernia is completely covered by skin, unlike an omphalocele which is covered by a thin translucent membrane. On the more severe end of the spectrum, omphalocele must be distinguished from rarer anomalies such as bladder exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy, as well as from the very rare limb-body wall defects and pentalogy of Cantrell. It is crucial to report all findings and obtain good clinical photographs for the expert reviewer.

Omphalocele is frequently (50% of cases or more) associated with additional birth defects (particularly cardiac, urogenital, brain, spina bifida), with certain complex anomaly patterns (pentalogy of Cantrell, OEIS), or with genetic syndromes (e.g. trisomies 13 and 18, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Donnai-Barrow syndrome). Omphalocele can occur with related anomalies that should also be identified and reported, such as intestinal malrotation and pulmonary hypoplasia.

Clinically, the size of the omphalocele correlates with the risk of associated anomalies and syndromes (the larger the omphalocele the higher the risk). Large omphaloceles require more complex surgeries, have a higher surgical risk, and are associated with higher mortality (e.g. due to respiratory insufficiency).

The birth prevalence of omphalocele is approximately 2–3 per 10 000 births (might be lower in Asian populations and higher in non-Hispanic blacks in the USA). Suggested non-genetic risk factors include folic acid insufficiency or deficiency, maternal obesity and pregestational diabetes, and possibly second-hand smoking and certain medications (e.g. methimazole).

Inclusions

Q79.2 Omphalocele (exomphalos)

Exclusions

Q79.3 Gastroschisis

Q79.8 Umbilical hernia

P02.69 Newborn affected by other conditions of umbilical cord

Checklist for high-quality reporting of omphalocele

| Omphalocele – Documentation Checklist |

Describe in detail. Avoid using just the term “omphalocele”; add further details:

Report whether specialty consultation(s) were done (including genetics, surgery), and if so, report the results. |

Suggested data quality indicators

| Category | Suggested Practices and Quality Indicators |

| Description and documentation | Review sample for documentation of key descriptors:

|

| Coding |

|

| Clinical classification |

|

| Prevalence |

|

| Key visuals | Distinguishing omphalocele from gastroschisis (side-by-side comparison):

|

Gastroschisis

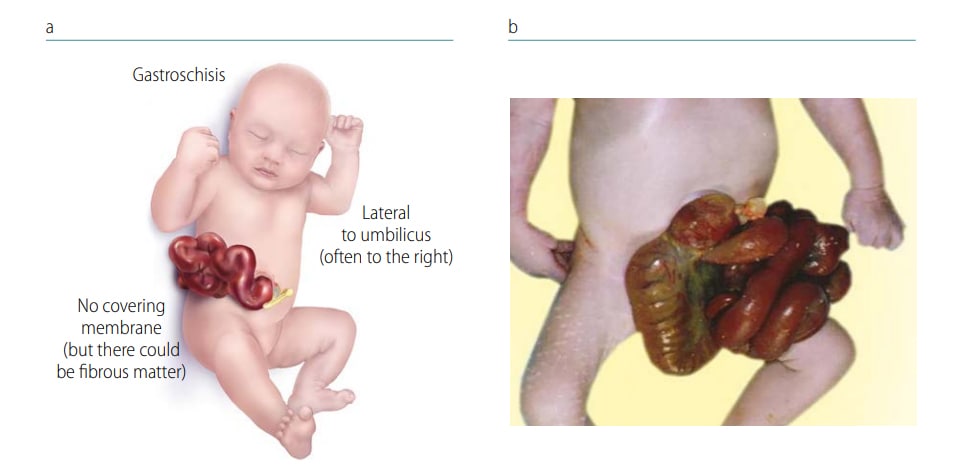

Gastroschisis is a birth defect of the anterior abdominal wall accompanied by herniation of the small intestine and part of the large intestine, and occasionally other abdominal organs. Two key findings in gastroschisis (Fig. 4.43, panels a, b) are location – the defect is lateral to the inserted umbilical cord (generally to the right) – and covering – there is an absence of a covering membrane, though the herniated organs might at times be covered by fibrous material due to in utero exposure to fluids. This presentation is in contrast to what is seen in omphalocele, in which the organs herniate centrally through a widened umbilical ring, and are covered by a thin, often translucent membrane (when intact).

Fig. 4.43. Gastroschisis

Photograph source: CDC–Beijing Medical University collaborative project.

Relevant ICD-10 codes

Q79.3 Gastroschisis Note:

Avoid using the generic Q79 code for congenital malformations of the musculoskeletal system not elsewhere classified. This generic code includes other anomalies such as omphalocele that must be distinguished from gastroschisis.

Diagnosis

Prenatal. Gastroschisis might be diagnosed or strongly suspected prenatally; however, it can be missed. Moreover, the distinction from omphalocele prenatally is difficult and error-prone. Also, in early pregnancy there is a normal physiologic hernia that might be confused with gastroschisis. For this reason, a prenatal diagnosis should always be confirmed postnatally. When this is not possible (e.g. termination of pregnancy or unexamined fetal death), the programme should have criteria in place to determine whether to accept or not accept a case based solely on prenatal data.

Postnatal. Careful examination of the newborn can confirm the diagnosis of gastroschisis and distinguish it from omphalocele and some other rare anomalies that might involve the anterior abdominal wall (e.g. limb-body wall defects, pentalogy of Cantrell). Note that sometimes the organs herniated in gastroschisis might be covered by fibrous material, which is thought to result from prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid in utero.

Clinical and epidemiologic notes

Distinguishing gastroschisis from omphalocele is important because these conditions have different risk factors, associated anomalies, approaches to treatments and outcomes.

With careful examination, the diagnosis of gastroschisis is usually straightforward. Rare conditions that might engender diagnostic confusion include limb-body wall defects and pentalogy of Cantrell. In these cases, several other anomalies are present. In limb- body wall defects, one can find atypical exencephaly/encephalocele, atypical facial clefts, and at times amniotic bands. For this reason, it is crucial to report all findings and obtain good clinical photographs for the expert reviewer.

Gastroschisis is frequently (80% or more of cases) an isolated, non-syndromic anomaly. Syndromes are very rare. However, gastroschisis often co-occurs with related anomalies, most often of the gut. These include intestinal malrotation, small intestinal atresia, microcolon, and several others. Pulmonary hypoplasia might also occur. These related anomalies can affect survival and long-term function.

The birth prevalence of gastroschisis varies widely, as much as between 0.5 to 10 per 10 000 births. Prevalence is several-fold higher in young mothers (especially < 19 years of age, but also < 29 years, compared to women 25–29 years). The prevalence has been increasing in several countries for unclear reasons. In addition to young maternal age, other suggested non-genetic risk factors include low body mass index, genitourinary tract infections, smoking, illicit drug use, possibly some medications (e.g. aspirin, antidepressants), and some other factors (e.g. change in paternity). The protective role of folic acid has been suggested but not proven.

Inclusions

Q79.3 Gastroschisis

Exclusions

Q79.2 Omphalocele (exomphalos)

Q89.81 Limb-body wall complex

Related codes

Q41 and sub-codes Intestinal atresia (e.g. Q41.2, atresia of the ileum)

Checklist for high-quality reporting

| Gastroschisis – Documentation Checklist |

Describe in detail. Avoid using only the term“gastroschisis” and specify the following details:

Take and report photographs: Show clearly the umbilical cord; can be crucial for review. Describe evaluations to find or rule out related and associated anomalies: If present, describe these anomalies. Report whether specialty consultation(s) were done (particularly surgery), and if so, report the results. |

Suggested data quality indicators

| Category | Suggested Practices and Quality Indicators |

| Description and documentation | Review sample for documentation of key descriptors:

|

| Coding |

|

| Clinical classification |

|

| Prevalence |

|

| Key visuals | Distinguishing omphalocele from gastroschisis (side-by-side comparison):

|