4.7 Congenital Malformations of the Digestive System

CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM OESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA/TRACHEO-OESOPHAGEAL FISTULA (Q39.0–Q39.2)

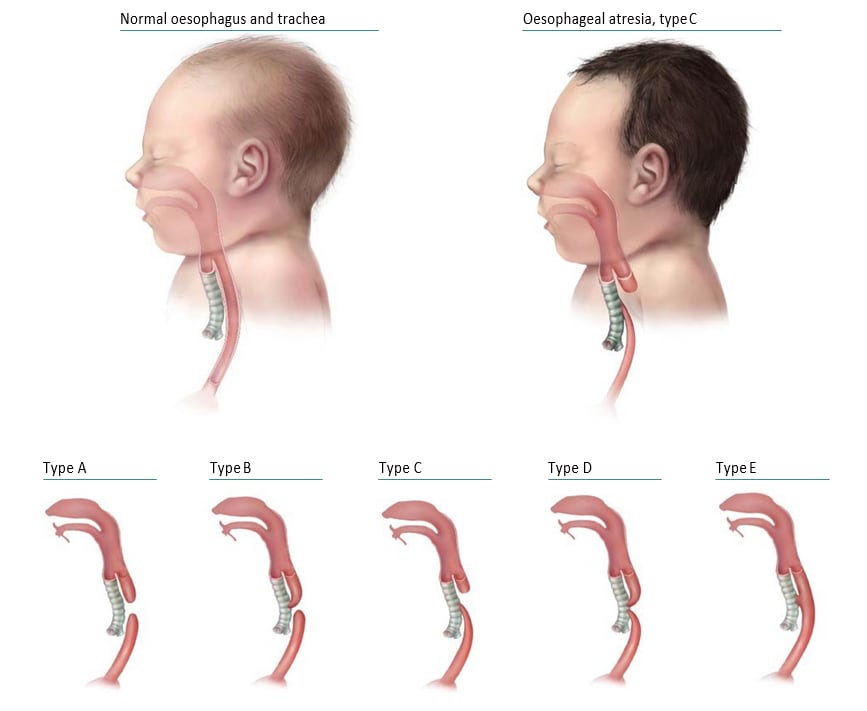

Oesophageal (esophageal) atresia is a congenital malformation characterized by the oesophagus ending in a blind pouch that does not connect to the stomach (see Fig. 4.28). Tracheo-oesophageal fistula (TEF or TOF) consists of a communication between the oesophagus and the trachea that is not normally present. Although it might occur alone, TEF is commonly associated with oesophageal atresia.

Fig. 4.28. Oesophageal atresia/tracheo-oesophageal fistula

The anatomical types of oesophageal atresia are:

- Type A: Oesophageal atresia without TEF

- Type B: Oesophageal atresia with proximal TEF

- Type C: Oesophageal atresia with distal TEF

- Type D: Oesophageal atresia with proximal and distal TEF

- Type E: TEF without oesophageal atresia.

Types A–D are typically recognized oesophageal atresia, with type C being by far the most common. Type E is a fistula without atresia and is variably ascertained by surveillance programmes.

Relevant ICD-10 codes

Q39.0 Atresia of oesophagus without fistula

Q39.1 Atresia of oesophagus with trachea-oesophageal fistula

Q39.2 Congenital trachea-oesophageal fistula without atresia

Diagnosis

Prenatal. Oesophageal atresia is rarely diagnosed prenatally but can be suspected if the stomach or stomach bubble cannot be visualized or if there is polyhydramnios (however, such excessive amniotic fluid has many causes). A prenatal diagnosis should always be confirmed postnatally. When this is not possible (e.g. termination of pregnancy or unexamined fetal death), the programme should have criteria in place to determine whether to accept or not accept a case based solely on prenatal data.

Postnatal. At birth, signs of oesophageal atresia include vomiting immediately after feeding, excessive drooling or mucus, and, if TEF is present, respiratory distress. Oesophageal atresia can be diagnosed radiographically when a feeding tube cannot pass from the pharynx into the stomach and, if there is no TEF, by an absence of air in the stomach.

TEF can be diagnosed by CT or MRI scan, surgery or autopsy. Because of the variability in symptoms, the diagnosis of TEF without oesophageal atresia might be delayed for weeks, months or even years.

Clinical and epidemiologic notes

Oesophageal atresia is frequently (55%) associated with additional birth defects (particularly cardiac, anorectal, skeletal/vertebral, and urogenital). Oesophageal atresia can occur in association with other structural anomalies, anomaly complexes (e.g. OAVS – Q87.04, VATER/VACTERL association – Q87.26) or genetic syndromes (e.g. trisomy 18 – Q91, trisomy 21 – Q90, CHARGE syndrome – Q30.01, Feingold syndrome – Q87.8, several others).

The birth prevalence of oesophageal atresia is approximately 1 per 3000 to 5000 births. No non-genetic risk factors have been consistently associated with oesophageal atresia with or without TEF. Advanced paternal age and assisted reproductive technologies have been associated with oesophageal atresia, but these associations require further study.

Inclusions

Oesophageal atresia with or without trachea-oesophageal fistula

Q39.0 Atresia of oesophagus without fistula

Q39.1 Atresia of oesophagus with trachea-oesophageal fistula

Q39.2 Congenital trachea-oesophageal fistula without atresia

Exclusions

(if occurring in the absence of oesophageal atresia or trachea-oesophageal fistula)

J39.8 Stenosis/stricture of trachea

Q32.1 Congenital malformations of trachea and bronchus (including absent/agenesis/atresia of trachea)

Q32.2 Congenital bronchomalacia

Q39.3 Congenital stenosis and stricture of oesophagus

Q39.4 Congenital oesophageal web

Checklist for high-quality reporting of oesophageal atresia with or without TEF

| Oesophageal Atresia with or without TEF – Documentation Checklist |

Describe in detail:

Describe evaluations to rule out additional malformations/associations/syndromes:

Take and report photographs: Show clearly oesophageal atresia and if present, TEF type; can be crucial for review. Report whether autopsy (pathology) findings are available and if so, report the results. |

Suggested data quality indicators

| Category | Suggested Practices and Quality Indicators |

| Description and documentation | Review sample of clinical description for documentation of key descriptors:

|

| Coding |

|

| Clinical classification |

|

| Prevalence |

|

LARGE INTESTINAL ATRESIA/STENOSIS (Q42.8–Q42.9)

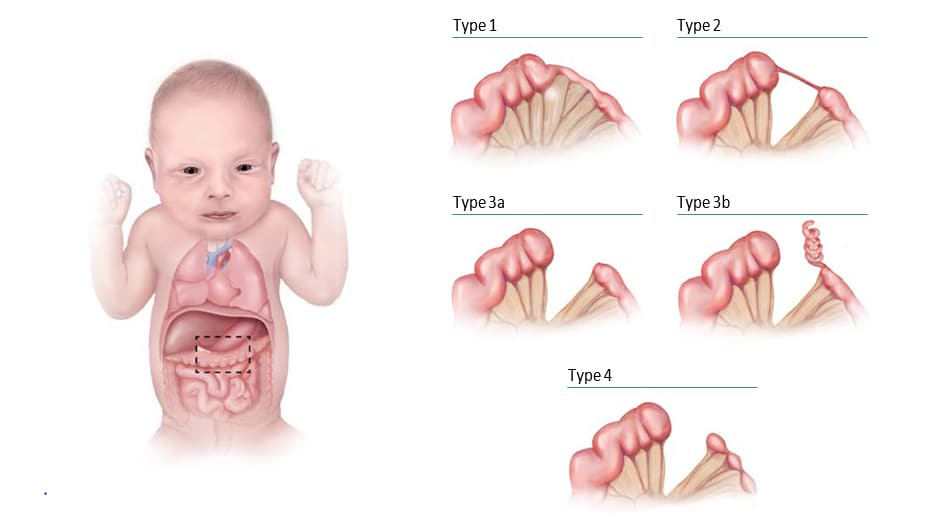

Fig. 4.29. Main types of large intestinal atresia

Large intestinal atresia or stenosis – also known as colonic atresia – is characterized by the complete (atresia) or partial obstruction of the opening (lumen) within the colon. The large intestine includes the ascending, transverse and descending portions of the colon and the sigmoid region.

Four types have been recognized (see Fig. 4.29). In type 1, the lumen is occluded by internal tissue (mucosal web) with intact mesentery. In type 2, the atretic segment is a fibrous cord, and connects the two ends of the large intestine. In type 3, the atretic segment occurs with a V-shaped mesenteric gap defect (in type 3b, there is an “apple peel” appearance of a portion of the gut). In type 4, the atresia involves two or more regions of the colon, with an appearance described as a string of sausages (approximately one third of all large intestinal atresias are type 4).

Congenital stenosis of the large intestine occurs less frequently than atresia and should be distinguished from acquired stenosis. Though extremely rare, total absence of the colon might occur.

Relevant ICD-10 codes

Q42 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of large intestine

(Note: Q42 is the generic ICD-10 code for atresia and stenosis of the large intestine. Avoid using this general code if more specific information is available.)

Q42.8 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of large intestine

Q42.9 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of large intestine, part unspecified

Diagnosis

Prenatal. These conditions are challenging to diagnose by prenatal ultrasound. If large intestinal atresia or stenosis is suspected, it should be confirmed postnatally.

Postnatal. Large intestinal atresia or stenosis should be suspected in the newborn infant who fails to pass meconium or stool, has abdominal distention and/or bilious vomiting. Symptoms of atresia might be delayed in the newborn but will usually appear within the first few days of life. Diagnosis is confirmed through direct imaging of the bowel by x-ray, barium enema, surgery or autopsy. Depending on the degree of obstruction, partial colonic stenosis might be diagnosed later, even weeks after delivery.

Clinical and epidemiologic notes

Compared to small intestinal atresia and anorectal atresia, large intestinal atresia is rare. Its prevalence is estimated to be approximately 1 in 20 000 births, and it represents less than 10% of all intestinal atresias.

Non-genetic risk factors include maternal varicella infection and possibly prenatal exposure to vasoconstrictive compounds, such as cocaine.

Inclusions

Q42.8 Large intestinal atresia or stenosis

Q42.8 Sigmoid atresia or stenosis

Q42.8 Agenesis of the recto-sigmoid portion of the colon

Q42.90 Colonic atresia or stenosis

Exclusions

Q41 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of small intestine

Q41.0 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of duodenum

Q41.1 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of jejunum

Q41.2 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of ileum

Q41.8 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of other specified parts of small intestine

Q41.9 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of small intestine, part unspecified

Q43.1 Hirschsprung’s disease

Q79.3 Gastroschisis with intestinal atresia

Apple peel intestinal atresia

Acquired colonic stenosis

Microcolon

Checklist for high-quality reporting

| Large Intestinal Atresia/Stenosis – Documentation Checklist |

Describe the anatomy in detail, using a combination of clinical, imaging, and surgical reports; specifically include information on the following elements:

Describe procedures to assess further additional malformations:

Copy and attach key imaging. Report findings of surgery or autopsy. Report whether specialty consultation(s) done, and if so, report the results. |

Suggested data quality indicators

| Category | Suggested Practices and Quality Indicators |

| Description and documentation | Review sample of clinical description for documentation of key descriptors:

|

| Coding |

|

| Clinical classification |

|

| Prevalence |

|

ANORECTAL ATRESIA/STENOSIS (Q42.0–Q42.3)

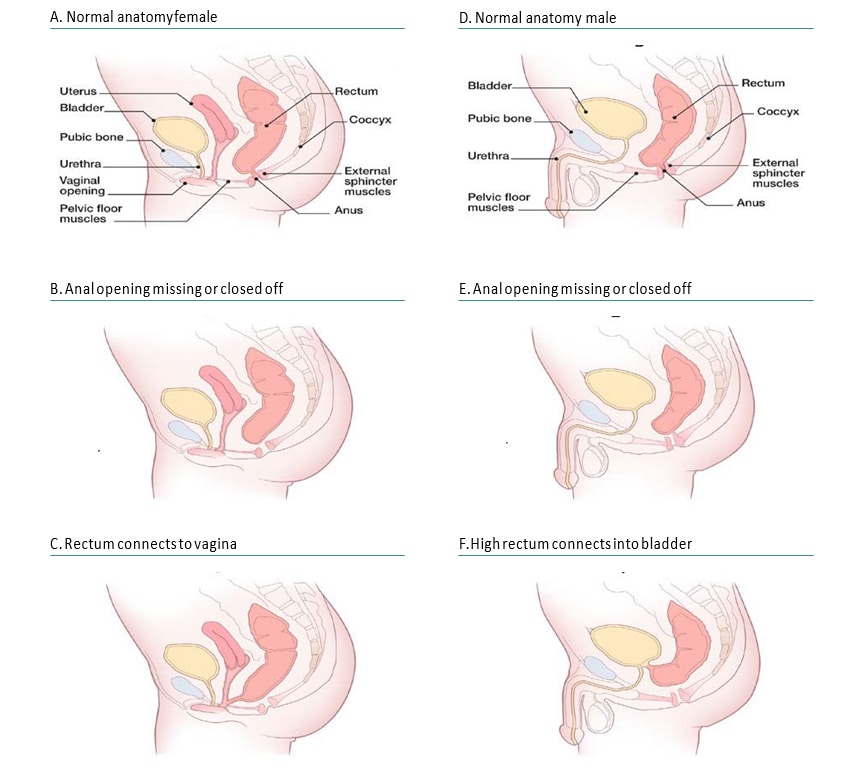

Anorectal anomalies include a wide spectrum of anomalies in which the atresia or stenosis involves the anus alone or an additional segment of the rectum. Imperforate anus is a term that properly reflects the outward appearance in the physical examination of a child, but internally the anomaly can be much more complex, involving the rectum, and is often associated with fistulas (e.g. Fig. 4.30, panel C – rectovaginal fistula in a girl, panel F – rectovesical fistula in a boy).

Fig. 4.30. Anorectal atresia/stenosis

Anorectal anomalies have been classified in different ways. A simple and practical approach classifies them as “low” or “high” lesions, depending on whether or not the rectum has descended into the sphincter complex (e.g. compare panel E – low lesion – with panel F – high lesion). Low and high lesions tend to vary by clinical presentations (e.g. presence or not of a dimple in the area of the anus), frequency of associated malformations (greater in high lesions), and surgical complexity.

Relevant ICD-10 codes

Q42.0 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of rectum with fistula

Q42.1 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of rectum without fistula

Q42.2 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of anus with fistula

Q42.3 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of anus without fistula

| Fistula present | Fistula absent | |

| Anorectal anomaly

(High) |

Q42.0 | Q42.1 |

| Anal anomaly

(Low) |

Q42.2 | Q42.3 |

Diagnosis

Prenatal. Anorectal anomalies might be difficult to diagnose prenatally by ultrasonography and might be missed if isolated. If an anal dimple is demonstrated or the bowel is dilated on ultrasound, this suggests an anorectal anomaly. For this reason, a prenatal diagnosis of anorectal anomalies should always be confirmed postnatally. When this is not possible (e.g. termination of pregnancy or unexamined fetal death), the programme should have criteria in place to determine whether to accept or not accept a case based solely on prenatal data.

Postnatal. Anal atresia or stenosis is usually easily recognized at birth by visual inspection during the newborn physical examination. If missed at birth, rectal atresia or stenosis might be suspected in the first 24 hours when the newborn develops abdominal distension; does not pass meconium or stool; or, when a fistula is present, if meconium is passed through the urethra or vagina. The diagnosis of rectal atresia or stenosis is confirmed through direct imaging of the bowel by radiography, barium enema, surgery or autopsy. As discussed, the external examination does not predict the level of the lesion.

Clinical and epidemiologic notes

Because only one third of anorectal anomalies are isolated, infants must be evaluated for the presence of additional anomalies. These include structural anomalies of the urinary tract, of the vertebrae or sacrum with tethered cord (the association of anorectal atresia with sacral defect and presacral mass forms the Currarino triad, often an autosomal dominant condition), and in females, with anomalies of the vagina and uterus (e.g. bicornuate uterus or uterus didelphys). In general, associated anomalies are more prevalent with higher rectal pouches.

Anorectal atresia is also part of some non-syndromic multiple congenital anomaly patterns, including caudal regression (Q89.80), exstrophy of the cloaca (Q64.10), OEIS (Q79.52; omphalocele, cloacal exstrophy, imperforate anus, spinal defects) and the VATER or VACTERL association (vertebral, anus, cardiac, trachea, oesophagus, renal, limb; Q87.26). Anorectal atresia is also seen in more than 100 genetic syndromes, including Townes-Brocks syndrome (autosomal dominant, SALL1 gene), cat-eye syndrome (tetrasomy 22q11), Opitz G-BBB syndrome (X-linked, MID1 gene), among many others.

Suggested non-genetic risk factors for anorectal atresia include thalidomide exposure and maternal pregestational diabetes.

Anorectal atresias as a group affect approximately 1 in 1000 to 5000 births, more commonly in males than females. Rectal atresia alone is very rare. Low-level lesions are more common than high-level lesions.

Inclusions

Rectal atresia or stenosis with or without fistula Anal atresia or stenosis with or without fistula

Q42.0 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of rectum with fistula

Q42.1 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of rectum without fistula

Q42.2 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of anus with fistula

Q42.3 Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of anus without fistula

Q42.3 Imperforate anus

Exclusions

Q43.5 Ectopic anus (e.g. anteriorly displaced anus)

Q43.7 Persistent cloaca

Notes: Several complex conditions have anorectal malformations as obligate (e.g. cloacal exstrophy) or frequently occurring (e.g. sirenomelia) components. Because they are so different clinically and epidemiologically from the simple or isolated forms of anorectal atresia, it is recommended that cases with these conditions be coded with the specific malformation complex code (e.g. cloacal exstrophy) in addition to the code for anorectal atresia (if present). This approach will help clarify whether there is a pattern such as OEIS (see Clinical and epidemiologic notes).

Q64.10 Bladder exstrophy

Q64.12 Cloacal exstrophy

Q43.7 Cloacal malformation including persistent cloaca

Q76.49 Sacral agenesis

Q87.2 Sirenomelia

Checklist for high-quality reporting

| Anorectal Atresia – Documentation Checklist |

Describe in detail, including:

Describe procedures to assess further additional malformations (e.g. spine radiographs, echocardiogram) and if one or more is present, describe these. Take and store photographs of anomaly and infant. Find and store key diagnostic imaging. Report findings of surgery or autopsy. Report whether specialty consultation(s) done, and if so, report the results. |

Suggested data quality indicators

| Category | Suggested Practices and Quality Indicators |

| Description and documentation | Review sample of clinical description for documentation of key descriptors:

|

| Coding |

|

| Clinical classification |

|

| Prevalence |

|