Anorectal Atresia/Stenosis

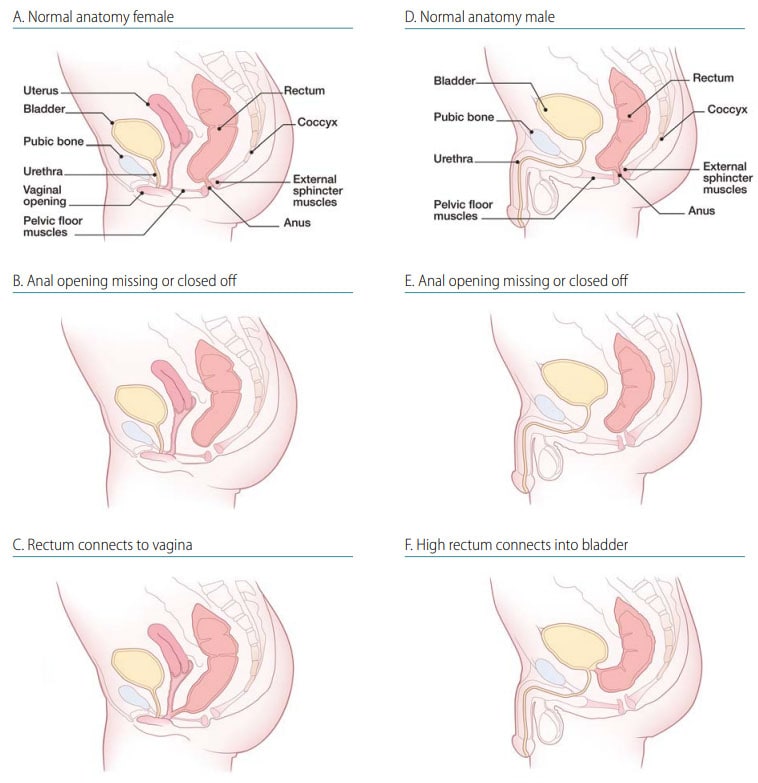

Anorectal anomalies include a wide spectrum of anomalies in which the atresia or stenosis can involve the anus alone or also a segment of the rectum. Imperforate anus is a term that properly reflects the outward appearance in the physical examination of a child, but internally the anomaly may be much more complex, involving the rectum and often associated with fistulas (e.g. Fig. 31, panel C – rectovaginal fistula in a girl; panel F – rectovesical fistula in a boy).

Fig. 31. Anorectal atresia/stenosis

- Location: “Low” or “high” lesions, depending on whether or not the rectum has descended into the sphincter complex (e.g.compare panel E [low lesion] –with panel F [high lesion]).

- Fistula: Presence or absence.

- Associated findings: Low and high lesions tend to vary by clinical presentations and frequency of associated malformations (greater in high lesions).

Diagnosis

Prenatal. Anorectal anomalies might be difficult to diagnose prenatally by ultrasonography and might be missed if an isolated anomaly. A prenatal diagnosis of anorectal anomalies should always be confirmed postnatally.

Postnatal. Anal atresia or stenosis is usually easily recognized at birth by visual inspection during the newborn physical examination. The external examination does not predict the level of the lesion. If missed at birth, rectal atresia or stenosis may be suspected in the first 24 hours when the newborn develops abdominal distension, does not pass meconium or stool, or when a fistula is present (meconium is passed through the urethra or vagina). The diagnosis of rectal atresia or stenosis is confirmed through direct imaging of the bowel by radiography, barium enema, surgery, or autopsy.

Clinical and epidemiologic notes

- urinary tract;

- vertebrae or sacrum with tethered cord (the association of anorectal atresia, sacral defect and presacral mass forms the Currarino triad, often an autosomal dominant condition); and

- vagina and uterus (e.g. bicornuate uterus or uterus didelphys) in females.

- Non-syndromic multiple congenital anomaly patterns include caudal regression, cloacal exstrophy, OEIS (omphalocele, bladder exstrophy, imperforate anus, spinal defects) and VATER/VACTERL (vertebral, anus, cardiac, trachea, oesophagus, renal, limb) association.

- More than 100 genetic syndromes are known to include anorectal anomalies, including Townes-Brock syndrome (autosomal dominant, SALL1 gene), cat-eye syndrome (tetrasomy 22q11), Opitz G-BBB syndrome (X linked, MID1 gene), among many others.

Checklist for high-quality reporting

| Anorectal Atresia – Documentation Checklist |

Describe in detail, including;

|