4.5e Pulmonary Valve Atresia (Q22.0)

Pulmonary valve atresia is a structural heart anomaly characterized clinically by cyanosis and anatomically by an imperforate pulmonary valve that blocks the flow of blood through the right ventricular outflow tract completely. The imperforate pulmonary valve can look like a membrane, or – because it failed to form altogether – the atresia takes the form of a muscular atretic segment.

Two main forms must be distinguished, based on whether or not a ventricular septal defect is present. These two forms differ in presentation, epidemiology and risk factors.

- In most cases, pulmonary valve atresia with a ventricular septal defect is considered as a conotruncal defect – specifically the more severe end of the spectrum of tetralogy of Fallot.

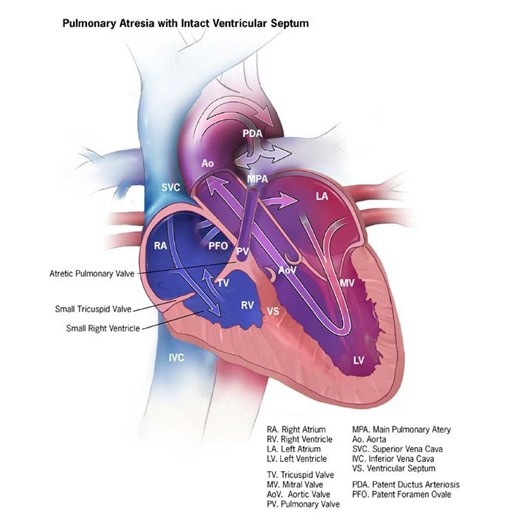

- Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum is a different entity (see Fig. 4.18) unrelated to conotruncal heart defects.

Fig. 4.18. Pulmonary valve atresia

Relevant ICD-10 codes

Q22.0 Pulmonary valve atresia

(Q21.0 Ventricular septal defect)

Diagnosis

Prenatal. Pulmonary valve atresiacan be suspected prenatally on a second trimester obstetrican atomic scan, using a combination of four-chamber and outflow tract views, and further characterized by fetal echocardiography. Because of diagnostic challenges, however, postnatal confirmation is necessary for a firm diagnosis.

Postnatal. Infants with pulmonary atresia (with or without ventricular septal defect) typically present early in the neonatal period with cyanosis and hypoxemia that worsens as the ductus closes. Echocardiography is the key diagnostic procedure, although other imaging techniques, including catheterization, might be necessary to better guide management and care.

Clinical and epidemiologic notes

Infants with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum typically present with cyanosis; massive cardiomegaly might also occur.

Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect can be associated with deletion 22q11, unlike the form with an intact ventricular septum.

The overall birth prevalence of pulmonary atresia is estimated to be approximately 1 in 7500 births. The birth prevalence of pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum is approximately 1 in 15 000 live births (more frequent among stillbirths).

Inclusions

Q22.0 Pulmonary valve atresia (without ventricular septal defect)

Q22.0 Pulmonary valve atresia with Q21.0 (ventricular septal defect)

Exclusions

Q22.1 Congenital pulmonary valve stenosis

Note:

- Some surveillance programmes group together pulmonary valve stenosis (Q22.1) and atresia (Q22.0). This is not recommended. Whereas severe pulmonary stenosis might present similarly to pulmonary atresia, mild forms of pulmonary stenosis are much more common, such that lumping stenosis with atresia generates a heterogeneous group of cardiac defects in which the severe forms cannot be accurately assessed and tracked.

- Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect is in most cases a conotruncal defect and should be grouped with tetralogy of Fallot and not with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum.

Checklist for high-quality reporting

| Pulmonary Atresia – Documentation Checklist |

Describe in detail the clinical and echocardiographic findings:

Look for and document extracardiac birth defects: In deletion 22q11, the heart anomaly can be associated with several internal and external anomalies, including cleft palate, spina bifida, vertebral anomalies or other defects. Report whether specialty consultation(s) were done: Report whether the diagnosis was made by a paediatric cardiologist, and whether the patient was seen by a geneticist. Report any genetic testing and results(e.g. chromosomal studies, genomic microarray, genomic sequencing). |

Suggested data quality indicators

| Category | Suggested Practices and Quality indicators |

| Description and documentation | Review sample of clinical descriptions for documentation of key elements:

|

| Coding |

|

| Clinical classification |

|

| Prevalence |

|