Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP): Clinical Testing Algorithm for Coccidioidomycosis

This clinical testing algorithm was made in collaboration with the Mycoses Study Group Education & Research Consortium and the Coccidioidomycosis Study Group.

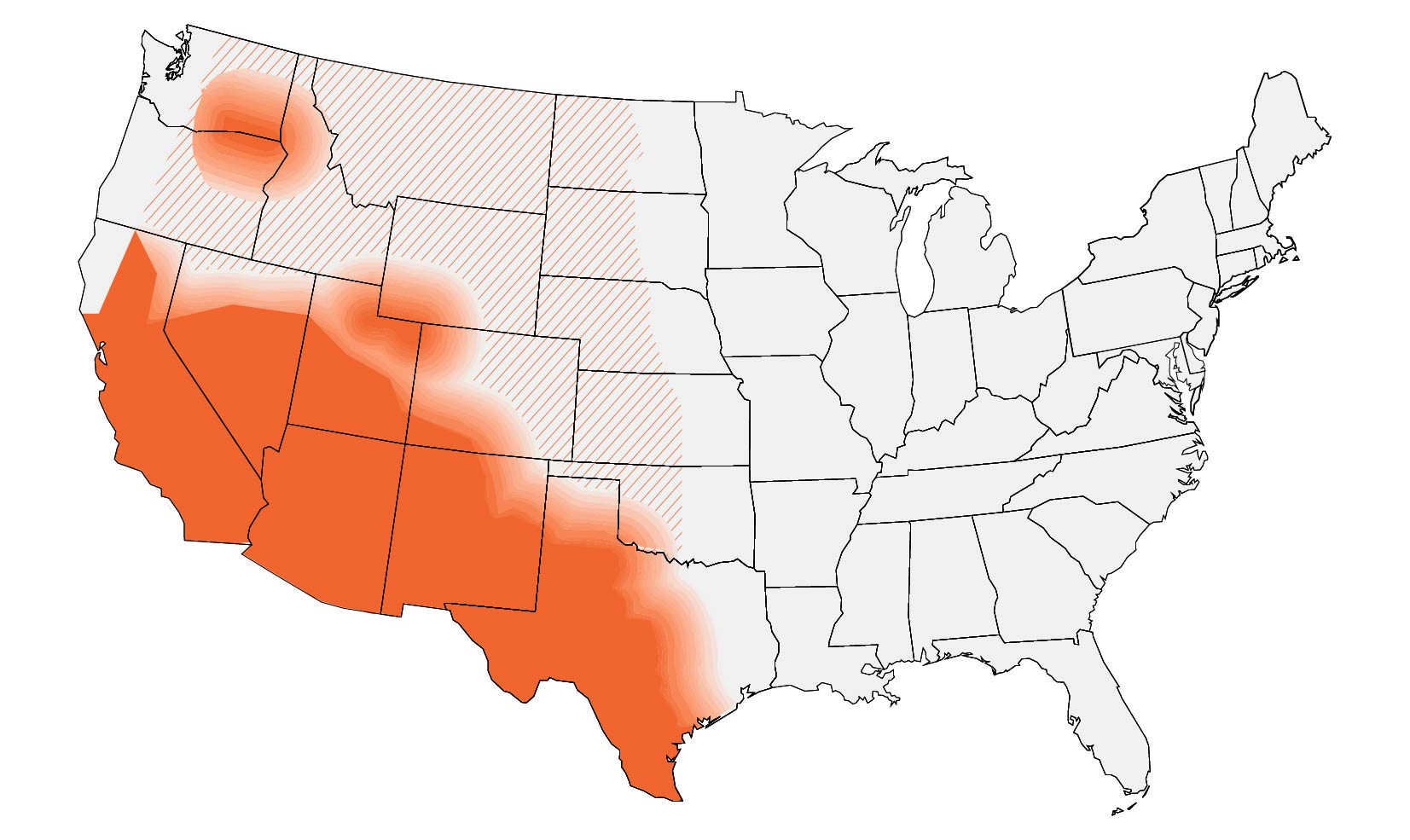

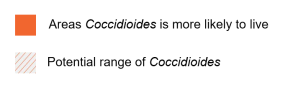

In the United States, coccidioidomycosis is endemic to the Southwest and parts of the Pacific. Globally, it is endemic in parts of South and Central America. These maps are approximations. Coccidioides is not distributed evenly and may not be present everywhere within the shaded areas. It may also be present outside of the areas indicated.

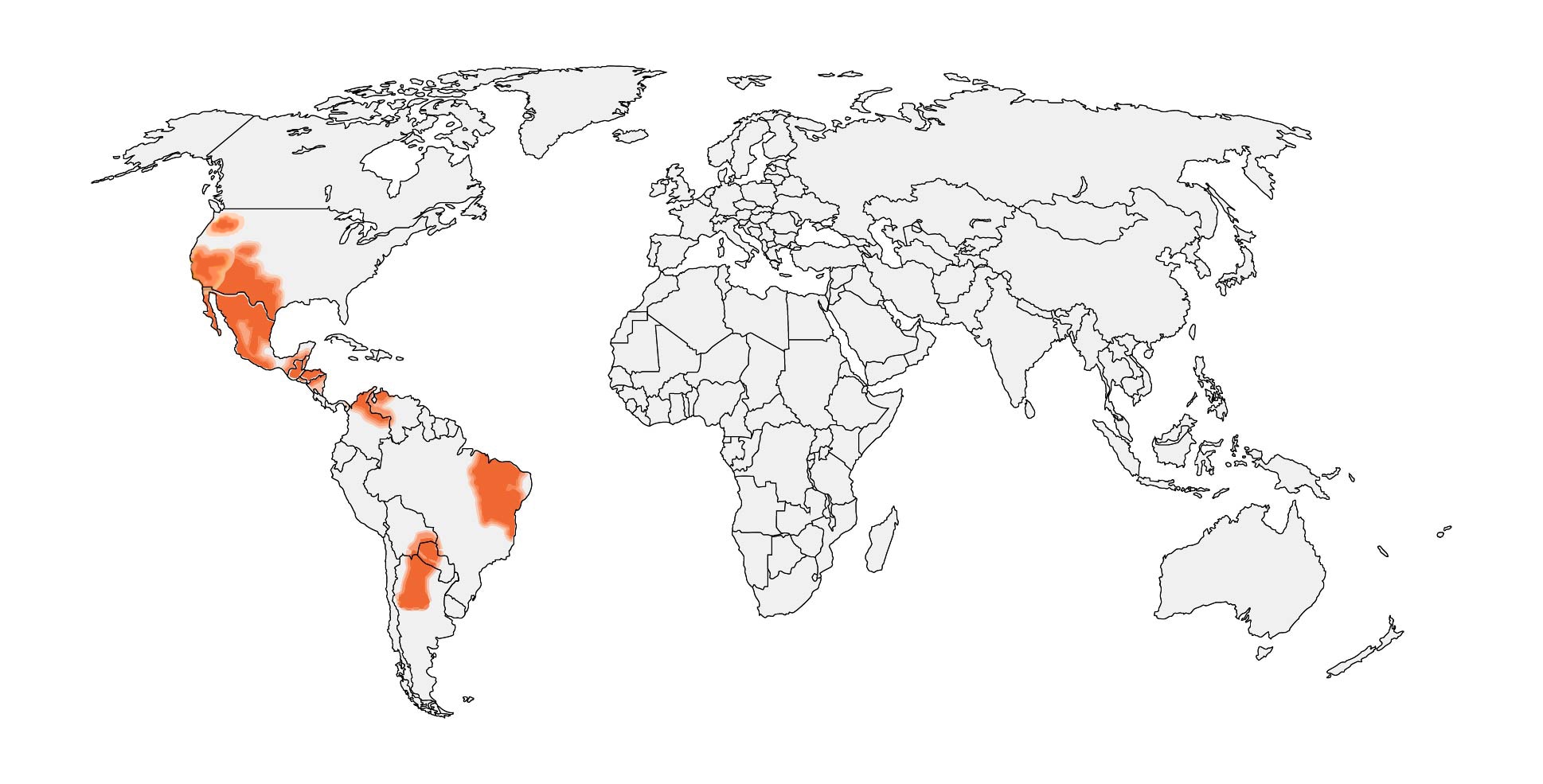

If a patient lives in or has traveled to a disease-endemic area and has:

1a. CAP of unknown etiology not responding to a course of empiric antibiotics

or

1b. Initial presentation of CAP (or erythema nodosum in the setting of recent respiratory symptoms) if people have:

- Lived in or traveled to highly endemic desert regions of Arizona (i.e. South-Central Arizona) or the San Joaquin Valley of California) OR

- Link to a known coccidioidomycosis outbreak

2. Consider serologic testing by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with immunodiffusion (ID) and complement fixation (CF)

- Note: initial testing with EIA or ID and CF may depend on availability and performance characteristics of test at facility

- IgM (+) or IgG (+): pulmonary coccidioidomycosis

- If an EIA test is positive, clinicians can consider follow-up testing with ID and CF to further establish the diagnosis. If ID and CF are negative after a positive EIA test, clinicians can consider repeat ID and CF 2-4 weeks later to confirm diagnosis. Patients with positive EIA results in highly endemic areas or with highly suggestive clinical findings (e.g., erythema nodosa), clinicians might start management for pulmonary coccidioidomycosis while awaiting results from ID or CF.

- IgM (-) and IgG (-): no infection OR immunosuppressed OR false negative

- False-negative results are possible. If clinical suspicion for coccidioidomycosis continues and if the patient is immunosuppressed or clinical illness is progressing rapidly, consider microscopy and culture of respiratory specimens from a bronchoscopy. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antigen detection can also be helpful but are done less frequently.

- Consider alternative diagnosis

- If high degree of suspicion remains, progression of illness, or recent symptom onset

- Repeat serology 2-6 weeks later

- Positive

- Pulmonary coccidiomycosis

- Positive

- Consider consulting infectious diseases or pulmonology

- Repeat serology 2-6 weeks later

Information About Coccidioidomycosis

See Clinical Infectious Diseases publication, Clinician Outreach and Communications Activity Call, and Medscape Article covering the coccidioidomycosis algorithm.

- Clinical Testing Guidance for Coccidioidomycosis, Histoplasmosis, and Blastomycosis in Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia for Primary and Urgent Care Providers | Clinical Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

- Webinar Thursday, September 21, 2023 – Algorithms for Diagnosing the Endemic Mycoses Blastomycosis, Coccidioidomycosis, and Histoplasmosis (cdc.gov)

- Three Cases of Community-Acquired Pneumonia (medscape.com)

About Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioidomycosis is an invasive fungal disease that often presents as community-acquired pneumonia in primary and urgent care settings. Coccidioidomycosis cannot be reliably distinguished from other causes of respiratory illness by signs or symptoms alone. Thus, the disease is commonly misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated with antibiotics—up to 70% of patients may receive inappropriate antibacterial drugs.1 In highlyendemic regions for coccidioidomycosis, erythema nodosum is commonly the presenting symptom.2 Climate change may be impacting the distribution in the United States, and travel-associated disease is common, particularly in people who have recently been to highly endemic areas like Arizona and California.1,2

When to Consider Testing for Coccidioidomycosis

Clinicians may consider testing for coccidioidomycosis in patients on an initial presentation of CAP (or erythema nodosum in the setting of recent respiratory symptoms) in patients who have lived in or have traveled to the highly endemic desert regions of Arizona (i.e., South-Central Arizona) or the San Joaquin Valley of California or a link to a known coccidiomycosis outbreak.

Clinicians may also consider testing for coccidioidomycosis in patients with CAP who have symptoms that did not improve following empiric antibiotics and have lived in or have traveled to generally endemic areas (Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, and Washington State, and Central and South America).4,5

How to Test for Coccidioidomycosis

We recommend ordering an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) antibody with immunodiffusion (ID) or complement fixation (CF) antibody test initially for coccidioidomycosis diagnosis. Initial testing with EIA or ID and CF may depend on availability and performance characteristics of test at facility. EIAs have a quicker turnaround time than ID and CF antibody testing. If the EIA is positive, clinicians may consider follow-up testing with ID and CF to rule out false positives and confirm the diagnosis. For patients in highly endemic areas or with highly suggestive clinical findings (e.g., erythema nodosa), clinicians might start management for pulmonary coccidioidomycosis while awaiting results from ID and CF. If the follow-up testing with ID or CF is negative, consider repeat ID or CF to rule out false negatives.

If the initial EIA test is negative, clinicians should consider alternative diagnoses. If a high degree of suspicion remains, progression of illness occurs, or if symptom onset was recent, repeat serology may be considered 2 to 6 weeks after the initial EIA test, or you may consult a specialist in infectious diseases or a pulmonologist. Note that antibody testing may be negative early in the illness course.

Antigen testing is available; however, it has primarily been studied in immunocompromised patients with moderately severe or disseminated disease or in meningitis.6 PCR and LFA can be helpful in diagnosing patients, but it is not readily available in many clinical settings.

Clinicians should refer to the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s coccidioidomycosis treatment guidelines or consult a specialist in infectious diseases when selecting therapy after a positive result.6

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | Population studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody tests | |||

| EIA (IgM & IgG) antibody7–9 | 59%–88% | 68%–96% (Cross reacts with other dimorphic fungi) | General patient population, immunocompromised population, patients with disseminated disease |

| Complement fixation (CF) antibody7,10,11 | 65%–83% | High | General patient population, immunocompromised population, patients with disseminated disease |

| Immunodiffusion (ID) antibody7 | 60% | 99% | General patient population, immunocompromised population, patients with disseminated disease |

| Lateral flow assay (LFA) antibody12 | 31% | 92% | General patient population |

| Antigen tests | |||

| EIA urine antigen15,16 | 37%–71% | High (but does cross-react with other dimorphic fungi) | General patient population, immunocompromised population, patients with disseminated disease |

| EIA serum antigen16,17 | 51%–73% | High (but does cross-react with other dimorphic fungi) | General patient population, immunocompromised population, patients with disseminated disease |

| Other tests | |||

| Histopathology5 | 23%–84% | High | General patient population, patients with diabetes, patients with disseminated disease |

| Cytology5 | 15%–75% | High | General patient population, patients with diabetes, patients with disseminated disease |

| PCR13,14 | 56%–75% | 99%–100% | General patient population |

- Benedict K, Ireland M, Weinberg MP, et al. Enhanced surveillance for coccidioidomycosis, 14 US states, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(8):1444-1452. doi:10.3201/eid208.171595

- Pu J, Miranda J, Minior D, Reynolds S, Rayhorn B, Ellingson KD, Galgiani JN. Improving Early Recognition of Coccidioidomycosis in Urgent Care Clinics Analysis of an Implemented Education Program. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. Accepted November 22, 2022.

- Gorris ME, Treseder KK, Zender CS, Randerson JT. Expansion of coccidioidomycosis endemic regions in the United States in response to climate change. GeoHealth. 2019;3(10):308-327. doi:10.1029/2019GH000209

- Marsden-Haug N, Goldoft M, Ralston C, et al. Coccidioidomycosis acquired in Washington State. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):847-850. doi:10.1093/cid/cis1028

- Smith CE, Beard RR. Varieties of coccidioidal infection in relation to the epidemiology and control of the diseases. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1946;36(12):1394-1402. doi:10.2105/AJPH.36.12.1394

- Wheat LJ, Knox KS, Hage CA. Approach to the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, blastomycosis and coccidioidomycosis. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2014;6(3):337-351. doi:10.1007/s40506-014-0020-6

- Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):e112-e146. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw360

- Malo J, Holbrook E, Zangeneh T, et al. Enhanced antibody detection and diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis with the MiraVista IgG and IgM detection enzyme immunoassay. Diekema DJ, ed. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(3):893-901. doi:10.1128/JCM.01880-16

- Malo J, Holbrook E, Zangeneh T, et al. Comparison of three anti-coccidioides antibody enzyme immunoassay kits for the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. Med Mycol. 2020;58(6):774-778. doi:10.1093/mmy/myz125

- Grys TE, Brighton A, Chang YH, Liesman R, Bolster LaSalle C, Blair JE. Comparison of two FDA-cleared EIA assays for the detection of Coccidioides antibodies against a composite clinical standard. Med Mycol. 2019;57(5):595-600. doi:10.1093/mmy/myy094

- Huppert M. Serology of coccidioidomycosis. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1970;41(1-2):107-113. doi:10.1007/BF02051487

- Blair JE, Coakley B, Santelli AC, Hentz JG, Wengenack NL. Serologic testing for symptomatic coccidioidomycosis in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts. Mycopathologia. 2006;162(5):317. doi:10.1007/s11046-006-0062-5

- Donovan FM, Ramadan FA, Khan SA, et al. Comparison of a novel rapid lateral flow assay to enzyme immunoassay results for early diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):e2746-e2753. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1205

- Dizon D, Mitchell M, Dizon B, Libke R, Peterson MW. The utility of real-time polymerase chain reaction in detecting Coccidioides immitis among clinical specimens in the Central California San Joaquin Valley. Med Mycol. 2019;57(6):688-693. doi:10.1093/mmy/myy111

- Vucicevic D, Blair JE, Binnicker MJ, et al. The utility of Coccidioides polymerase chain reaction testing in the clinical setting. Mycopathologia. 2010;170(5):345-351. doi:10.1007/s11046-010-9327-0

- Durkin M, Connolly P, Kuberski T, et al. Diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis with use of the Coccidioides antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(8):e69-e73. doi:10.1086/592073

- Kassis C, Durkin M, Holbrook E, Myers R, Wheat L. Advances in diagnosis of progressive pulmonary and disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(6):968-975. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa188

- Durkin M, Estok L, Hospenthal D, et al. Detection of Coccidioides antigenemia following dissociation of immune complexes. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16(10):1453-1456. doi:10.1128/CVI.00227-09