HIV and People Who Inject Drugs

Data for 2020 should be interpreted with caution due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to HIV testing, care-related services, and case surveillance activities in state and local jurisdictions. While 2020 data on HIV diagnoses and prevention and care outcomes are available, we are not updating this web content with data from these reports.

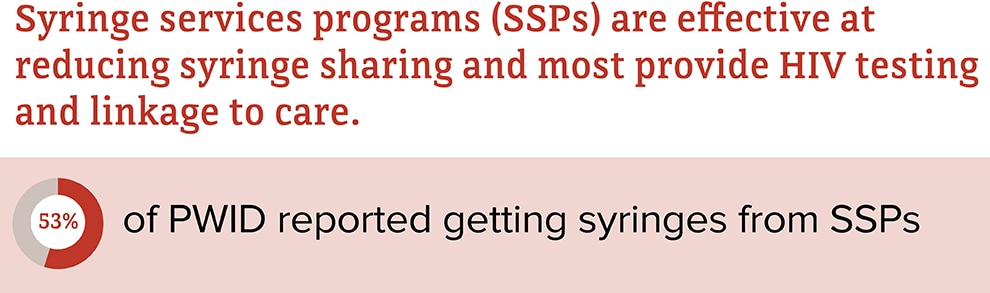

Although HIV diagnoses among PWID have remained stable in recent years, injection drug use in some areas of the United States have created prevention challenges and placed new populations at risk for HIV. This highlights the need for strengthened HIV prevention efforts for PWID, such as expanding coverage and support for comprehensive syringe services programs (SSPs).

HIV Risk Behaviors

The risk of getting or transmitting HIV varies widely depending on the type of exposure or behavior. Most commonly, people get or transmit HIV through anal or vaginal sex, or sharing needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment—for example, cookers.

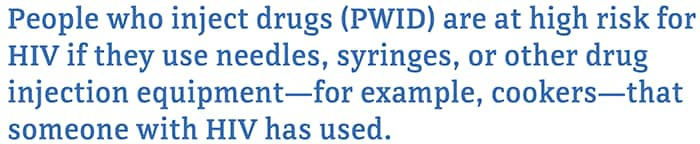

Syringe Sharing

Sharing needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment means using a needle or syringe after someone else used it to inject drugs or medicine or for tattoos or piercings.

Source: CDC. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: injection drug use – 23 U.S. Cities, 2018 [PDF – 2 MB]. HIV Surveillance Special Report 2020; 24.

HIV Prevention

Syringe Services Programs

Syringe services programs (SSPs) are community-based prevention programs that provide a range of services, including access to sterile needles and syringes, facilitation of safe disposal of used syringes, and provide and link people to other important services and programs, such as substance use disorder treatment, vaccination, testing, and linkage to care and treatment for infectious diseases.

Source: CDC. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: injection drug use – 23 U.S. Cities, 2018 [PDF – 2 MB]. HIV Surveillance Special Report 2020; 24.

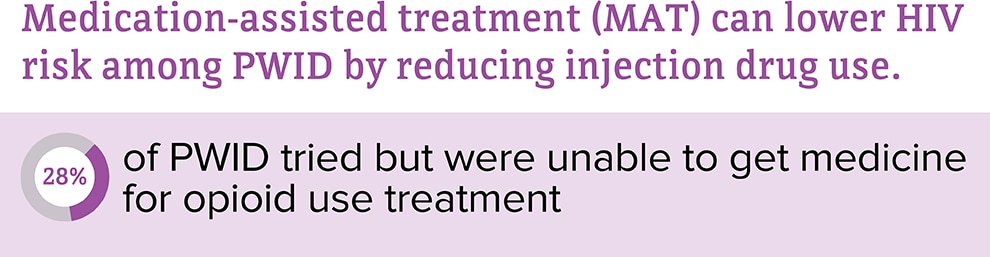

Medication-Assisted Treatment

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) combines medications and behavioral therapy to treat substance use disorders and prevent overdose.

Source: CDC. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: injection drug use – 23 U.S. Cities, 2018 [PDF – 2 MB]. HIV Surveillance Special Report 2020; 24.

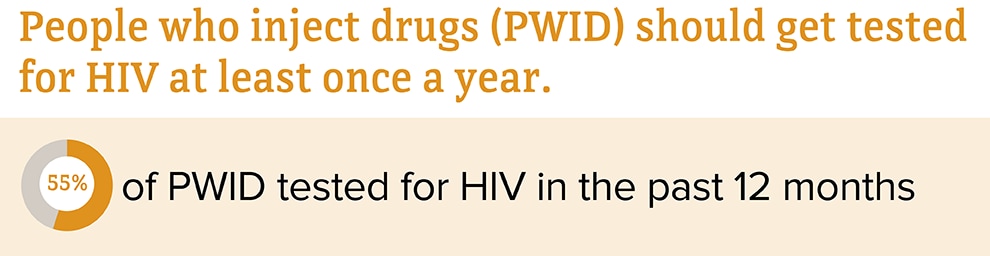

HIV Testing

HIV testing tells you whether or not you have HIV. CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. People with certain risk factors should get tested at least once a year.

Source: CDC. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: injection drug use – 23 U.S. Cities, 2018 [PDF – 2 MB]. HIV Surveillance Special Report 2020; 24.

HIV Diagnoses

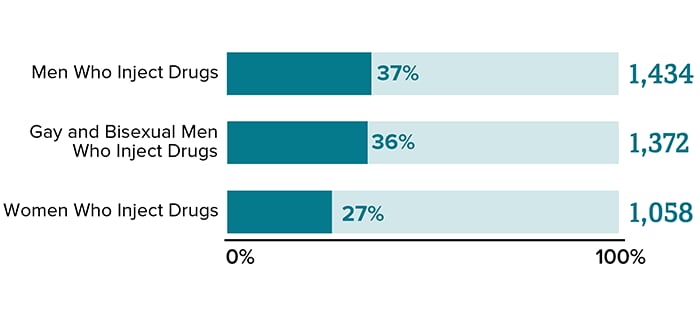

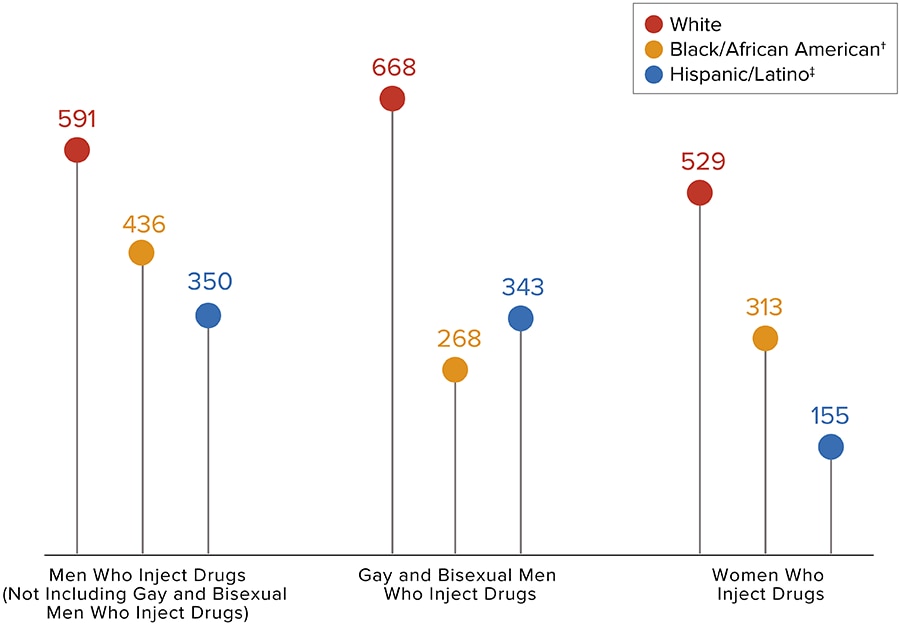

Diagnoses refers to the number of people who received an HIV diagnosis during a given year. Adult and adolescent PWIDa accounted for 10% (3,864)b of the 37,968 new HIV diagnoses in the United States (US) and dependent areasc in 2018 (2,492 cases were attributed to injection drug use and 1,372 to male-to-male sexual contactd and injection drug use).

Source: CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (updated). HIV Surveillance Report 2020;31.

* Includes infections attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use (men who reported both risk factors).

† Black refers to people having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa. African American is a term often used for people of African descent with ancestry in North America.

‡ Hispanic/Latino people can be of any race.

Source: CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (updated). HIV Surveillance Report 2020;31.

The numbers have been statistically adjusted to account for missing transmission categories. Values may not equal the total number of PWID who received an HIV diagnosis in 2018.

* Includes infections attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use (men who reported both risk factors).

Source: CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (updated). HIV Surveillance Report 2020;31

* Based on sex assigned at birth and includes transgender people.

† Black refers to people having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa. African American is a term often used for people of African descent with ancestry in North America.

‡ Hispanic/Latino people can be of any race.

Source: CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (updated). HIV Surveillance Report 2020;31.

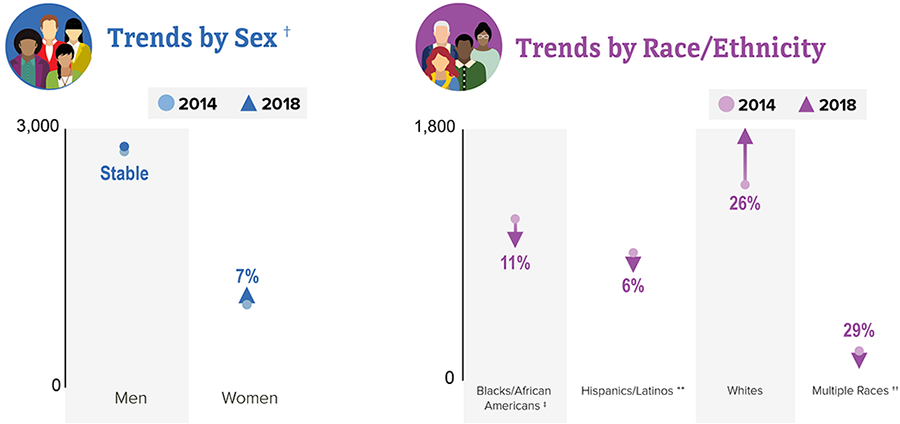

From 2014 to 2018, HIV diagnoses remained stable among PWID overall. While progress has been made with reducing HIV diagnoses among some groups of PWID, efforts will continue to focus on lowering diagnoses among all PWID.

This chart does not include subpopulations representing 2% or less of all PWID who received an HIV diagnosis in 2018.

* Includes infections attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use (men who reported both risk factors).

† Based on sex assigned at birth and includes transgender people.

‡ Black refers to people having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa. African American is a term often used for people of African descent with ancestry in North America.

** Hispanic/Latino people can be of any race.

†† Changes in subpopulations with fewer HIV diagnoses can lead to a large percentage increase or decrease.

Source: CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (updated). HIV Surveillance Report 2020;31.

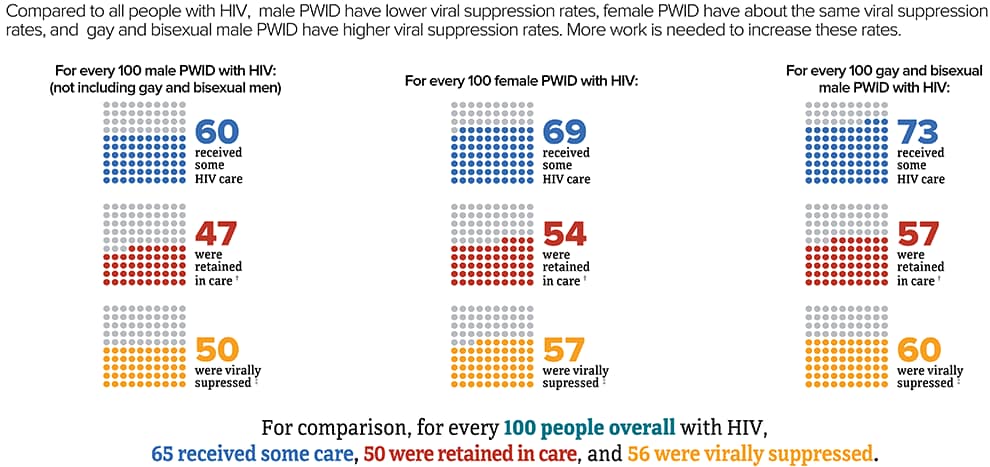

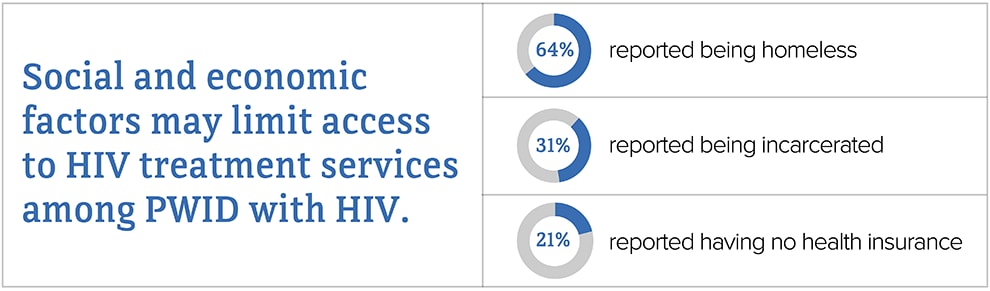

PWID With HIV

People with HIV who take HIV medicine as prescribed can live long, healthy lives and help prevent HIV transmission.

It is important for PWID to know their HIV status so they can take medicine to treat HIV if they have the virus. Taking HIV medicine every day can make the viral load undetectable. People who get and keep an undetectable viral load (or remain virally suppressed) can stay healthy for many years and will not transmit HIV to their sex partners.

Keeping an undetectable viral load also likely reduces the risk of transmitting HIV through shared needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment, though we don’t know by how much.

* Includes infections attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use (men who reported both risk factors).

† Had 2 viral load or CD4 tests at least 3 months apart in a year.

‡ Based on most recent viral load test.

Source: CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States 2014–2018 [PDF – 3 MB]. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2020;25(1).

Source: CDC. Selected national HIV prevention and care outcomes [PDF – 2 MB] (slides).

Source: CDC. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: injection drug use – 23 U.S. Cities, 2018 [PDF – 2 MB]. HIV Surveillance Special Report 2020; 24.

Deaths

In 2018, there were 4,905 deaths among PWID with diagnosed HIV in the US and dependent areas. These deaths could be from any cause.

Prevention Challenges

Many communities do not have the resources or support to establish effective syringe services programs (SSPs). Barriers to SSPs include legal and regulatory issues, insufficient funding, and misunderstandings about the effectiveness and safety of SSPs.

The prescription opioid and heroin crisis has led to increased numbers of PWID, placing new populations at risk for HIV. The crisis has disproportionately affected nonurban areas, where HIV prevalence rates have been low historically. These areas have limited services for HIV prevention and treatment and substance use disorder treatment.

PWID may also engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as having sex without protection (like condoms or medicine to prevent or treat HIV), having sex with multiple partners, or trading sex for money or drugs. Studies have found that young PWID are more likely than older PWID to have sex without a condom, have more than one sex partner, and have sex partners who also inject drugs.

PWID may face stigma and discrimination. Although substance use disorder is a health issue that requires treatment, it is often viewed as a criminal activity. Stigma and mistrust of the health care system may prevent PWID from seeking HIV testing, care, and treatment.

PWID may not have access to substance use disorder treatment, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD). MAT and MOUD can lower HIV risk among PWID by reducing injection drug use. Also, PWID who have HIV are more likely to take HIV medicine as prescribed if they are on MAT or MOUD. Barriers may include lack of prescribers, legal and regulatory issues, insurance coverage, and confusion about the use of MAT and MOUD.

PWID are also at risk for getting other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), blood-borne diseases, and bacterial infections. Having another STD can greatly increase the likelihood of getting or transmitting HIV through sex. For people with HIV, getting hepatitis B or C can put them at increased risk for serious, life-threatening complications. PWID can also have other bacterial infections, such as endocarditis and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus.

What CDC Is Doing

CDC is pursuing a high-impact HIV prevention approach to maximize the effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions and strategies. Funding state, territorial, and local health departments and community-based organizations (CBOs) to develop and implement tailored programs is CDC’s largest investment in HIV prevention. This includes longstanding successful programs and new efforts funded through the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative. In addition to funding health departments and CBOs, CDC is also strengthening the HIV prevention workforce and developing HIV communication resources for consumers and health care providers.

- Under the integrated HIV surveillance and prevention cooperative agreement, CDC awards around $400 million per year to health departments for HIV data collection and prevention efforts. This award directs resources to the populations and geographic areas of greatest need, while supporting core HIV surveillance and prevention efforts across the US.

- In 2019, CDC awarded $12 million to support the development of state and local Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. plans in the nation’s 57 priority areas. To further enhance capacity building efforts, CDC uses HIV prevention resources to fund the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) with $1.5 million per year to support strategic partnerships, community engagement, peer-to-peer technical assistance, and planning efforts.

- In 2020, CDC awarded$109 million to 32 state and local health departments that represent the 57 jurisdictions across the United States prioritized in the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative. This award supports the implementation of state and local Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. plans.

- Under the flagship community-based organization cooperative agreement, CDC awards about $42 million per year to community organizations. This award directs resources to support the delivery of effective HIV prevention strategies to key populations.

- In 2019, CDC awarded a cooperative agreement to strengthen the capacity and improve the performance of the nation’s HIV prevention workforce. New elements include dedicated providers for web-based and classroom-based national training, and technical assistance tailored within four geographic regions.

- CDC supports intervention programs that deliver services to PWID such as Community PROMISE, a community-level HIV prevention program that uses role-model stories and peer advocates to distribute prevention materials within social networks.

- CDC provides guidance on SSP activities that can be supported with CDC funds and how CDC-funded programs may request to direct resources to support SSPs.

- CDC provides technical assistance on SSP implementation. SSPs are proven and effective community-based prevention programs that provide a range of services, including access to and disposal of sterile syringes and injection equipment, vaccination, testing, and linkage to infectious disease care and substance use treatment. SSPs play a key role in preventing HIV and other health problems among PWID.

- CDC uses cutting-edge technology to detect and respond to clusters of HIV transmission, and supports state and local responses to HIV outbreaks traced to injection drug use.

- CDC supports programs to deliver biomedical approaches to HIV prevention and treatment for PWID such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for people at risk, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to lower the chances of getting HIV after an exposure, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) or medicines to treat HIV.

- CDC maintains the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance(NHBS) system among populations at risk for HIV. Every three years, NHBS collects information on HIV infection and behaviors from PWID in jurisdictions with high HIV prevalence, including drug use and sexual risk behaviors, testing behaviors, and use of HIV prevention services.

- Through its Let’s Stop HIV Together campaign, CDC offers resources about HIV stigma, testing, prevention, and treatment. This campaign is part of the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative.

a Adult and adolescent PWID aged 13 and older.

b Includes infections attributed to injection drug use and those attributed to male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use (men who reported both risk factors).

c Unless otherwise noted, the term United States (US) includes the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the 6 dependent areas of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, the Republic of Palau, and the US Virgin Islands.

d The term male-to-male sexual contact is used in CDC surveillance systems. It indicates a behavior that transmits HIV infection, not how people self-identify in terms of their sexuality. This web content uses the term gay and bisexual men to represent gay, bisexual, and other men who reported male-to-male sexual contact.

- CDC-INFO 1-800-CDC-INFO (232-4636)

- CDC HIV Website

- Let’s Stop HIV Together

- CDC HIV Risk Reduction Tool

- Find Testing Sites Near You

- CDC. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among persons who inject drugs–National HIV Behavioral Surveillance: injection drug use – 23 U.S. Cities, 2018 [PDF – 2 MB]. HIV Surveillance Special Report 2020; 24.

- CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 [PDF – 7 MB]. HIV Surveillance Report 2020;31.

- CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2014-2018 [PDF – 3 MB]. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2020;25(1).

- CDC. HIV risk behaviors. Accessed January 28, 2020.

- CDC. Selected national HIV prevention and care outcomes [PDF – 2 MB] [slides].

- CDC. Summary of information on the safety and effectiveness of syringe services programs (SSPs). Accessed January 28, 2020.