Flu, Tdap, and COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women – United States, April 2022

Note: Minor corrections have been made to some estimates in this report since its original publication.

Summary

Vaccination of pregnant women* with influenza (flu) vaccine, tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap), and COVID-19 vaccine can decrease the risk for flu, pertussis (whooping cough), and COVID-19 among pregnant women and their infants. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all women who are or might be pregnant during the flu season receive flu vaccine, which can be administered at any time during pregnancy [1]. ACIP also recommends that women receive Tdap during each pregnancy, preferably during the early part of gestational weeks 27–36 [2, 3]. In addition, COVID-19 vaccines have been available in the United States since December 2020 and are currently recommended for all people aged ≥ 6 months, including women who are pregnant, breastfeeding, or trying to get pregnant now, or might become pregnant [4, 5]. To assess flu, Tdap, and COVID-19 vaccination coverage among women pregnant during the 2021–22 flu season, CDC analyzed data from an Internet panel survey conducted during April 2022. Among 2,015 survey respondents who were pregnant anytime during October 2021–January 2022, 48.4% reported receiving flu vaccine before or during their pregnancy. Among 838 respondents who had a live birth by their survey date, 45.8% reported receiving Tdap during pregnancy. Among 1,392 women pregnant at the time of survey completion, 60.5% received ≥ 1 dose of COVID-19 vaccine and 54.4% had completed their COVID-19 vaccine primary series. Flu and Tdap vaccination coverage was highest among women who reported receiving a provider offer or referral for vaccination (62.3% and 63.7%, respectively). Similarly, COVID-19 vaccination coverage was high among pregnant women who had received a provider recommendation (≥1 dose: 75.5%; series completion: 68.1%). Flu and COVID-19 vaccination coverage was similar among non-Hispanic Black (Black) and non-Hispanic White (White) women, but racial and ethnic disparities in Tdap coverage among pregnant women persist [6]: Black women had lower Tdap coverage than White women; Hispanic women had higher flu and COVID-19 vaccination coverage but similar Tdap coverage, compared with White women. Provider offers or referrals for vaccination in combination with tailored conversations to educate patients and address their concerns could help increase flu, Tdap, and COVID-19 vaccination coverage among pregnant women.

Methods

An Internet panel survey was conducted to assess end-of-season flu, Tdap, and COVID-19 vaccination coverage among women pregnant during the 2021–22 flu season; similar surveys have been conducted since April 2011. The survey was conducted during March 29–April 16, 2022, among women aged 18–49 years who reported being pregnant anytime since August 1, 2021, through the date of their survey. Participants were recruited from a large, pre-existing, opt-in Internet panel of the general population operated by Dynata (https://www.dynata.com) through both Dynata’s GenPop and Dynamix systems. Among 14,792 women who elected to answer the screening questions, 2,692 were eligible, and of these, 2,513 completed the survey (completion rate† = 93.4%). Data were weighted to reflect pregnancy status and outcome at the time of interview, age, race and ethnicity, and geographic distribution of the total U.S. population of pregnant women. Analysis of flu vaccination coverage was limited to 2,015 women pregnant anytime during October 2021–January 2022. A woman was considered to have been vaccinated against flu if she reported having received a dose of flu vaccine since July 1, 2021, and before or during her most recent pregnancy. To accommodate the optimal timing for Tdap vaccination during 27–36 weeks’ gestation, analysis of Tdap coverage was limited to women pregnant anytime since August 1, 2021, who had a live birth by their survey date. A woman was considered to have received Tdap if she reported receiving a dose of Tdap during her most recent pregnancy. Among 954 women with a recent live birth, 116 (12.2%) were excluded because they did not know whether they had ever received Tdap (10.1%) or did not know whether they received it during their pregnancy (2.1%), leaving a final analytic sample of 838; the proportion of pregnant women who received both flu and Tdap vaccines was assessed among these same 838 women. COVID-19 vaccination coverage was assessed among 1,392 women who reported being pregnant at the time of survey completion. A woman was considered to have received ≥ 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine if she reported receiving ≥1 dose of any brand of COVID-19 vaccine. A woman was considered to have completed the COVID-19 vaccine primary series if she reported receiving 2 doses of the Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines or a single dose of the Janssen vaccine; for women who reported being immunocompromised‡ (n=38), an additional dose was required to be considered to have completed their primary series. We also assessed COVID-19 vaccine booster dose coverage among 748 women who completed their primary series; receipt of at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine beyond the primary series was considered receipt of a booster. Finally, we assessed place of flu, Tdap, first (or only) COVID-19, and COVID-19 booster vaccination. It should be noted that among 301 respondents who we determined to have received a COVID-19 booster, 56 (18.6%) were excluded from place of vaccination analyses because they were not asked about place of booster vaccination due to the following: 1) they were early responders who encountered an erroneous skip pattern (n=22), which was later corrected in the survey, or 2) they indicated not receiving a booster (n=34). SAS-callable SUDAAN software (version 11.0.1; RTI International) was used to conduct all analyses. Differences between groups were determined using t-tests with significance set at p<0.05. Increases or decreases noted in this report represent statistically significant differences.

Results

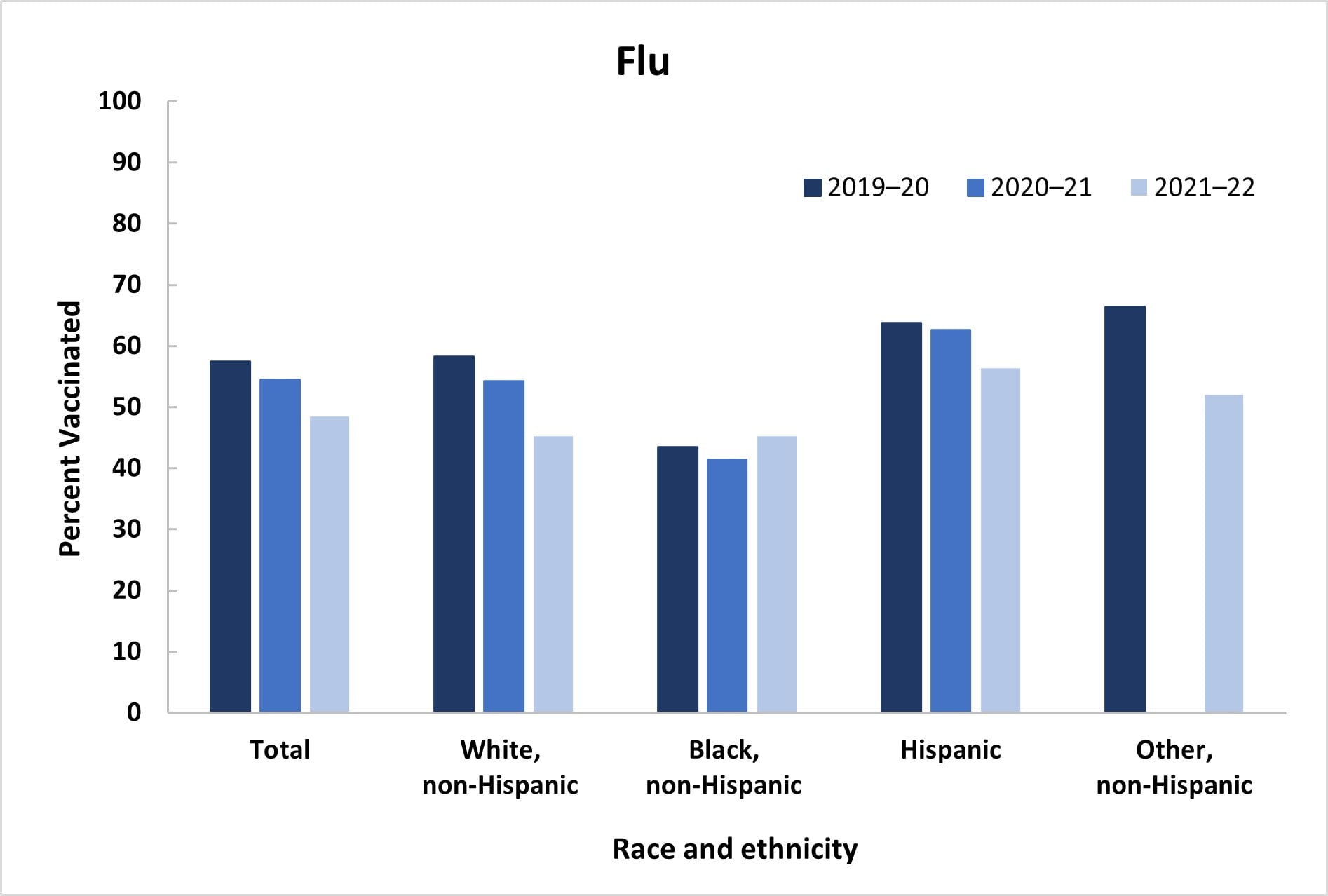

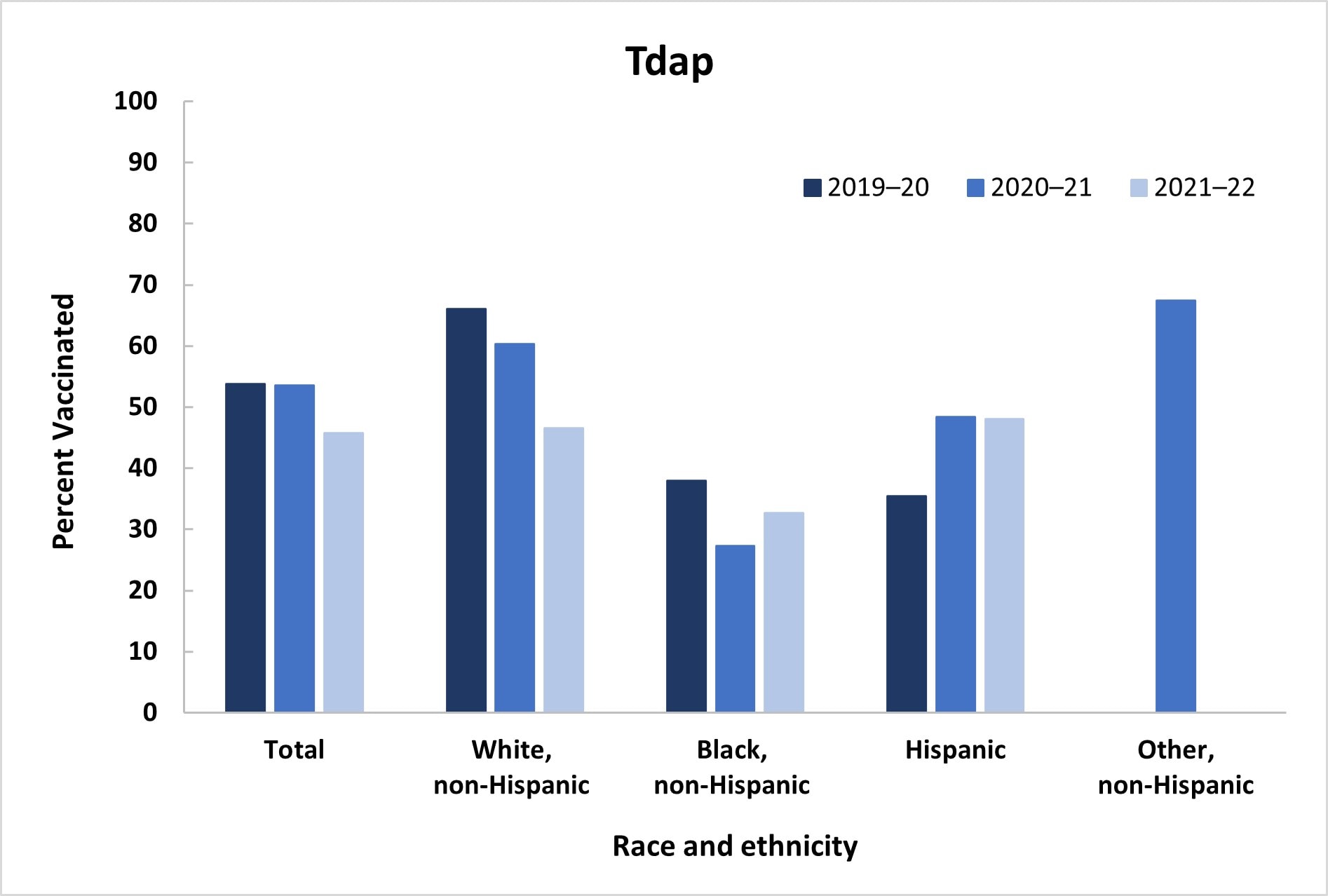

Among women pregnant anytime during October 2021–January 2022, 48.4% reported receiving a dose of flu vaccine since July 1, 2021, a decrease from 54.5% during the previous season; Tdap coverage during pregnancy among women with a recent live birth also decreased, from 53.5% in 2020–21 to 45.8% in 2021–22 (Table 1, Figure 1). Receipt of both flu and Tdap vaccines was reported by 22.6% of women with a recent live birth, a decrease from the previous season (30.7%). Flu vaccination coverage was highest among Hispanic women (56.3%), while Black women (45.2%) and women of non-Hispanic Other race and ethnicity (Other) (52.0%) had coverage similar to that of White women (45.2%). Tdap coverage was lowest among Black women (32.7%), whereas coverage among Hispanic (48.1%) women was similar to coverage among White women (46.6%). Flu and Tdap vaccination coverage decreased for White women compared with coverage during the previous season (Flu: 54.2% to 45.2%; Tdap: 60.3% to 46.6%); no other differences in coverage by race and ethnicity over the past three seasons were observed (Figure 1). Lower flu vaccination coverage was observed among those with less education, who were not working, were living below poverty, living in a rural area, living in the South, had 1–5 provider visits, and did not have high-risk conditions for flu, compared with referent groups. Higher Tdap coverage was observed among women aged 25–34 years and those who were not working, compared with referent groups.

A provider offer or referral for flu vaccination during the 2021–22 flu season was reported by 70.2% of respondents pregnant between October and January; 6.4% reported receiving a provider recommendation but no offer or referral, and 23.3% reported not receiving a provider recommendation for flu vaccine (Table 1). Flu vaccination was highest among those with a provider offer or referral for vaccination (62.3%) compared with those who reported receiving a provider recommendation but no offer or referral (31.8%) and no recommendation (12.2%). Among Tdap-eligible respondents, 70.1% reported receipt of an offer or referral for Tdap, while 5.8% received a provider recommendation with no offer or referral, and 24.1% did not receive a recommendation for Tdap. Coverage with Tdap was higher among women with an offer or referral (63.7%) than those without a recommendation (1.2%); a stable coverage estimate could not be calculated for those with a provider recommendation for Tdap but no offer or referral due to small numbers.

Among women who were pregnant at the time they completed the survey, 60.5% reported receiving ≥ 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and 54.4% reported completing their primary COVID-19 vaccine series; among those who had completed their primary series, 41.0% reported receiving a COVID-19 booster (Table 2). COVID-19 vaccination coverage was highest among Hispanic women (series completion: 63.3%), compared with White women (series completion: 49.4%), who had coverage similar to Black women (series completion: 52.4%) and Other women (series completion: 62.9%). Lower COVID-19 vaccination coverage was observed among women who were less educated, not working, living below poverty, living in rural areas, living in the South, had no prenatal insurance, no high-risk conditions for COVID-19, and had not received an influenza vaccination during the 2021–22 season, compared with reference groups. COVID-19 booster vaccination coverage was similar across most characteristics studied, but was lower among women living in the South, and West compared with those living in the Northeast. Receipt of a provider recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination was reported by 70.5% of women. Similar to flu and Tdap vaccination coverage, COVID-19 vaccination coverage was higher among women with a provider recommendation than those without a recommendation (series completion: 68.1% vs. 22.0%); the survey did not include questions about offer or referral for COVID-9 vaccination, nor related questions pertaining to COVID-19 booster receipt.

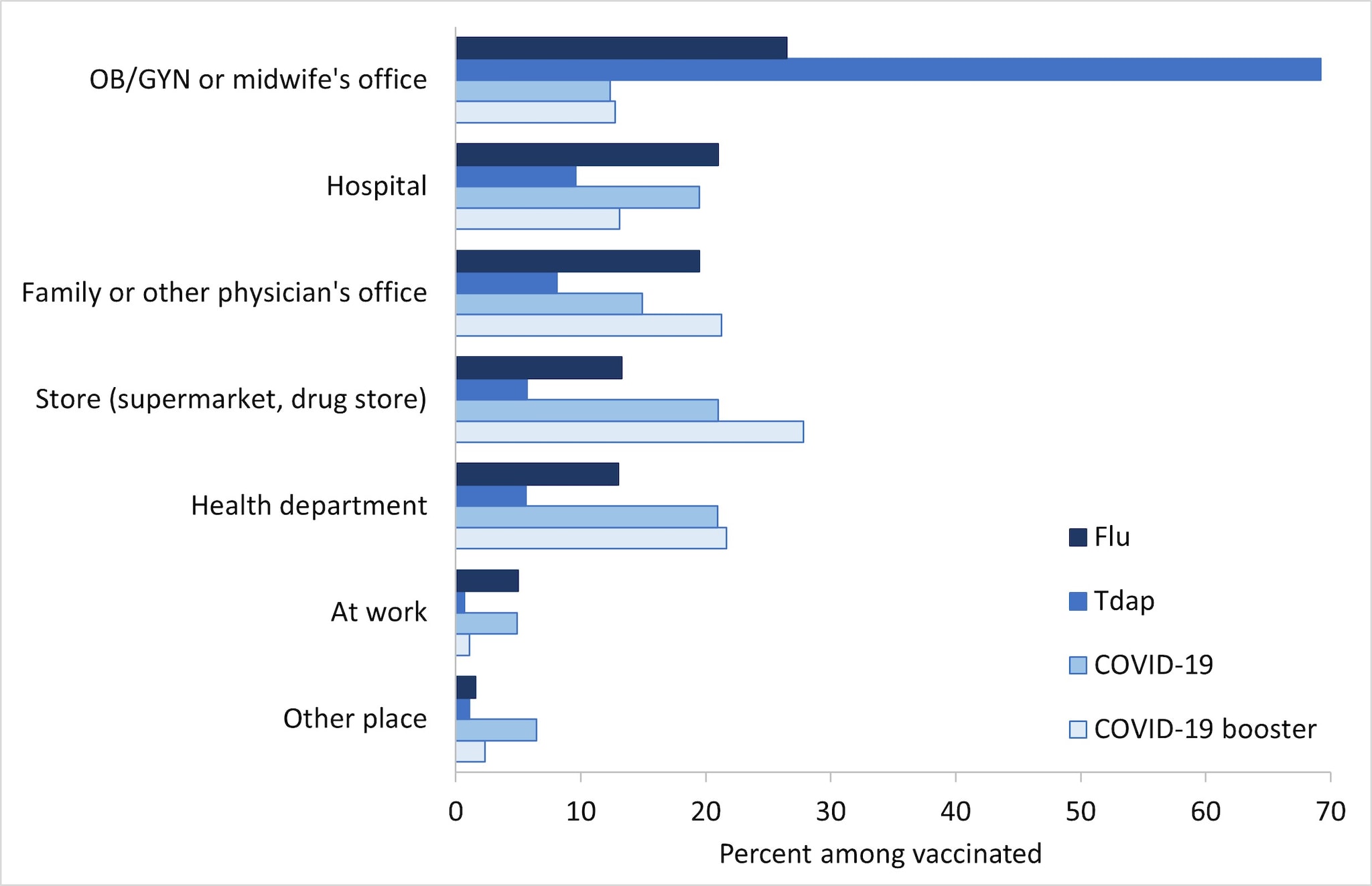

Place of flu vaccination among pregnant women in the 2021–22 flu season was most often the office of an obstetrician/gynecologist (OB/GYN) or midwife (26.5%), followed by a hospital (21.0%), family or other physician’s office (19.5%), store (supermarket, drug store, pharmacy) (13.3%), and health department (13.0%) (Figure 2). The most commonly reported place of Tdap vaccination among women with a live birth was an OB/GYN or midwife’s office (69.2%), followed by a hospital (9.6%), and family or other physician’s office (8.1%). Place of COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women was most often a store (21.0%), followed by a health department clinic (20.9%), hospital (19.5%), family or other physician’s office (14.9%), and an office of an obstetrician/gynecologist (OB/GYN) or midwife (12.4%). The most commonly reported place of COVID-19 booster vaccination among pregnant women was a store (27.8%), followed by a health department clinic (21.7%), family or other physician’s office (21.2%), hospital (13.1%), and an OB/GYN or midwife’s office (12.8%).

Discussion

Findings from this survey indicate that maternal flu and Tdap vaccination coverage has decreased, and that approximately half of pregnant women did not receive a flu vaccine and more than half did not receive a Tdap vaccine. In addition, 45% of pregnant women had not completed their COVID-19 vaccine primary series, and of those who did complete their primary series approximately 60% did not receive a booster. Not receiving these recommended vaccines leaves pregnant women and their infants more vulnerable to flu, whooping cough, and COVID-19 and potentially serious complications including adverse birth outcomes, hospitalization, and death [7-11]. As seen in previous reports, flu and Tdap vaccination coverage was highest among pregnant women with a provider offer or referral for vaccination [6]. Similarly, higher COVID-19 vaccination coverage was associated with receipt of a provider recommendation, which has been reported previously [12, 13]. Yet approximately one-quarter of women indicated not receiving a provider recommendation for vaccination for either flu or Tdap vaccine, and nearly 30% reported not receiving a provider recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination. Providers are encouraged to follow the Standards for Adult Immunization Practice by assessing vaccination status at every clinical encounter, strongly recommending vaccines that their patients need, administering needed vaccines or referring patients to a vaccination provider, and documenting vaccines administered in the immunization information system [14]. CDC has resources to assist providers in effectively communicating the importance of vaccination, such as sharing specific reasons why the recommended vaccines are right for the patient and highlighting positive experiences with vaccines (personally or in their practice) [14]. Another available resource is the ACOG immunization toolkit, which includes communication strategies for providers, as well as extensive information on vaccine financing and coding that could address perceived financial barriers, a commonly reported barrier to stocking vaccines in provider offices [15, 16].

The observed decrease in maternal flu and Tdap vaccination coverage is concerning. In the April 2021 Internet Panel Survey, we found that nearly half of pregnant women surveyed reported being somewhat or very hesitant about either influenza or Tdap vaccination during pregnancy, and those who reported being hesitant or not confident about maternal vaccines were less likely to report receiving influenza and Tdap vaccines [17]. In addition, previous examination of reasons for non-vaccination have highlighted maternal concerns about the safety of flu, Tdap, and COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy, particularly with regard to safety risks to the baby, and lack of knowledge about the recommendation to receive Tdap during every pregnancy [6, 12, 18]. Providers can tailor patient communications and education accordingly to help strengthen their recommendations for vaccination. ACIP recommendations for maternal flu and Tdap vaccination are well established, and studies have consistently affirmed the safety and effectiveness of maternal vaccination for women, fetuses, and infants [1, 2, 19]. Data also support the safety of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy [20]. Providers can share this information with their pregnant patients in an effort to alleviate vaccine hesitancy and increase acceptance of recommended vaccines.

Flu and Tdap vaccination coverage for both Black and Hispanic women has been stagnant for three seasons and has now decreased for White women in the 2021–22 season [6, 21]. Disparities in Tdap coverage continue to be observed for Black women, who had the lowest coverage, but for Hispanic women coverage was similar to that of White women due to the drop in coverage among White women [6, 21]. Unlike in previous seasons, Black women had similar flu vaccination coverage to that of White women during the 2021–22 season, also due to the drop in coverage among White women. As seen previously, Hispanic women had the highest flu vaccination coverage; the same pattern in coverage by race and ethnicity was observed for maternal COVID-19 vaccination [6, 21]. Factors such as knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about vaccines, including mistrust as a result of past medical racism and experimentation, and structural barriers related to accessing vaccines such as not having regular access have been shown to contribute to lower vaccination rates in Black adults generally [22-24]. In the April 2021 Internet panel survey, we found that Black women were more likely to report being hesitant about flu and Tdap vaccines [17].

A decrease in flu and Tdap vaccination coverage among White women has not been observed previously [6, 21]. Data from national surveys of adults have found that White adults are less likely than Black and Hispanic adults to report being concerned about getting COVID-19 or thinking COVID-19 vaccination is important [25, 26]. White adults are more likely than Black and Hispanic adults to report that they probably or definitely will not get a COVID vaccine [25-27]. These behavioral and social drivers of COVID-19 vaccination might influence their feelings about other vaccines as well, including flu and Tdap.

Estimates for COVID-19 vaccination coverage among pregnant women from the Internet panel survey are lower than from other data sources. From the nationally representative National Immunization Survey-Adult COVID Module, as of March 26, 2022, ≥ 1 dose COVID-19 vaccine coverage was 74.8% compared with 60.5% from the Internet panel survey, and 73.4% were fully vaccinated compared with 54.4% from the Internet panel survey [25]. In addition, based on data from the Vaccine Safety Datalink, a collaboration between CDC and multiple integrated health systems, Covid-19 booster vaccine coverage was 49.6% among fully vaccinated individuals who were pregnant during the week ending February 26, 2022, compared with 41.0% from the Internet panel survey [28]. Therefore, caution should be used when considering these estimates.

Despite longstanding ACIP recommendations, maternal vaccination with flu and Tdap vaccines is suboptimal, and missed opportunities to vaccinate are common; especially concerning is the drop in coverage since the previous season, particularly among White women, which needs to be further explored. COVID-19 vaccination coverage is suboptimal as well. Findings in this report reinforce the strong association between provider recommendation and offer of or referral for vaccination, and maternal vaccination. During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it is more important than ever for pregnant women to receive recommended vaccines, as pregnant women are at increased risk for severe illness from both flu and COVID-19, and health care resources could become limited as both flu and SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) viruses may be circulating simultaneously this fall. Providers should take the opportunity to ensure that pregnant women are vaccinated against flu, Tdap, and COVID-19. Vaccination coverage of pregnant women with all recommended vaccines can be increased through implementation of patient education about ACIP vaccination recommendations and safety and benefits of maternal vaccination in combination with evidence-based practices, such as screening patients for recommended vaccinations at every opportunity, reminders to notify providers that their patients need vaccinations, and system-level changes that make vaccinations part of the routine workflow, as well as having a culture of vaccination in the office [8]. Racial disparities in vaccination coverage could decrease with consistent provider offers or referrals for vaccination, in combination with multicomponent health system and community-based interventions [14, 29-31].

Limitations

Interpretation of the results in this report should take into account several limitations of the estimates produced from the Internet panel survey. First, the sample may not be representative of all pregnant women in the United States because the survey was conducted among a smaller group of volunteers who were already enrolled in a preexisting, national, opt-in, general-population Internet panel rather than a randomly selected sample of all pregnant women in the United States. Some bias might remain after weighting adjustments, for example, due to the exclusion of women with no Internet access and/or the self-selection processes for entry into the panel and participation in the survey. Estimates might be biased if the selection processes for entry into the Internet panel and a woman’s decision to participate in this survey were related to receipt of vaccination. Second, due to small sample size, we were not able to assess vaccination coverage separately among some racial and ethnic groups such as American Indian/Alaska Native persons, who are less likely to receive recommended vaccinations [32]. Third, all results are based on self-report and not validated by medical record review; therefore, coverage estimates might be subject to recall or social desirability bias and could be over- or underestimates. Fourth, for Tdap, coverage estimates might be subject to uncertainty, given the exclusion of 12.2% of women with unknown Tdap vaccination status. Sensitivity analysis showed that actual Tdap coverage could have ranged from 40.2% to 52.5% in 2022. Finally, formal statistics were used to determine differences in vaccination coverage between groups in this non-probability sample and results should be interpreted with caution [33]. Despite these limitations, Internet panel surveys are considered a useful assessment tool for timely evaluation of maternal vaccination coverage among pregnant women.

* The authors acknowledge that not every person who can become pregnant identifies as a woman. However, this survey was conducted among people who self-reported as female gender. Therefore, we use ‘pregnant women’ throughout.

† A survey response rate requires specification of the denominator at each stage of sampling. During recruitment of an online opt-in survey sample, such as the Internet panels described in this report, these numbers are not available; therefore, a response rate cannot be calculated. Instead, the survey completion rate is provided.

‡ Women were considered immunocompromised if they reported the following medical conditions: 1) immunocompromised state (weakened immune system) from solid organ transplant, or 2) immunocompromised state (weakened immune system) from blood or bone marrow transplant, immune deficiencies, HIV, use of corticosteroids, or use of other immune weakening medicines.

Authors

Katherine E. Kahn, MPH1,2; Hilda Razzaghi, PhD2; Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD2; Tami H. Skoff, MS3; Sascha R. Ellington, PhD4; Carla L. Black, PhD2

1Leidos, Inc., Atlanta, GA; 2Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; 3Division of Bacterial Disease, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases; 4 Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC

Abbreviations: Ref=referent group

* Respondents pregnant anytime during October 2021–January 2022 were included in the analyses to assess influenza vaccination coverage for the 2021–22 season. Women who reported receiving an influenza vaccination since July 1, 2021, before or during their pregnancy, were considered vaccinated.

† Respondents pregnant since August 1, 2021, and had recently delivered a live birth were included in the analyses to assess Tdap vaccination coverage. Women who reported receiving a Tdap vaccination during their pregnancy were considered vaccinated.

‡ Korn-Graubard 95% confidence interval.

§ Statistically significant difference compared with referent group

|| Race/ethnicity was self-reported. Respondents identified as Hispanic might be of any race. The “Other” race category included Asians, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders, and women who selected “other” or multiple races.

¶ Poverty status was defined based on the reported number of persons living in the household and annual household income, according to U.S. Census poverty thresholds. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html

** Rurality was defined using ZIP codes where >50% of the population resides in a nonmetropolitan county, a rural U.S. Census tract, or both, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration’s definition of rural population. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html

†† Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

‡‡ Respondents pregnant on their survey date were asked what medical insurance or medical care coverage they had; respondents who had already delivered were asked what they had during their most recent pregnancy. Women considered to have public insurance selected at least one of the following: Medicaid, Medicare, state-sponsored medical plan, or other government plan. Respondents considered to have private/military insurance selected private medical insurance and/or military medical care and did not select any type of public insurance.

§§ Estimates do not meet the NCHS standards of reliability. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_175.pdf

|||| Excluded women from influenza vaccination analyses who did not report having a provider visit since July 2021 (n=12).

¶¶ Received provider offer/referral for both influenza and Tdap vaccines.

*** Received a combination of provider offer/referral, recommendation with no referral, or no recommendation for influenza or Tdap vaccines that does not include receipt of offer/referral for both vaccines or no recommendation received for both vaccines. For example, the respondent might have received an offer/referral for influenza vaccine and a recommendation with no referral for Tdap.

††† Did not receive a provider recommendation for influenza or Tdap vaccine.

‡‡‡ Conditions other than pregnancy associated with increased risk for serious medical complications of influenza include chronic asthma, a lung condition other than asthma, a heart condition, diabetes, a kidney condition, a liver condition, obesity, or a weakened immune system caused by a chronic illness or by medicines taken for a chronic illness. Women who were missing information were excluded from analysis (n=28).

- The IPS weighting methodology changed in April 2021; estimates for 2019–20 have been re-calculated with the new survey weights.

- For women of Other race/ethnicity, the 2020–21 flu estimate and 2019–20 and 2021–22 Tdap estimates did not meet the NCHS standards of reliability. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_175.pdf

- The only statistically significant differences in coverage by race and ethnicity across seasons were a decrease in vaccination coverage among White women from 2020–21 to 2021–22 for both flu (54.2% to 45.2%) and Tdap (60.3% to 46.6%).

| Abbreviations: Ref=referent group |

| * Respondents who reported being pregnant at the time of the survey were included in the analysis. Those who reported receiving at least 1 dose of COVID-19 vaccine before or during their current pregnancy were considered vaccinated. To be considered fully vaccinated, respondents must have received at least 2 doses of a 2-dose vaccine (i.e., Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, or brand that requires two shots) or 1 dose of a 1-dose vaccine (i.e., Johnson and Johnson (Janssen) (requires 1 shot)); if a respondent reported being immunocompromised, she should also have received at least one additional booster dose to be considered fully vaccinated. |

| † Respondents who reported being pregnant at the time of the survey and being fully vaccinated against COVID-19, as described above, were included in the booster analysis. Respondents were considered to have received a COVID-19 booster vaccine if they reported receiving at least 1 dose of COVID-19 vaccine beyond what is required to be considered fully vaccinated. |

| ‡ The total unweighted number and weighted proportion of respondents in the sample. |

| § Korn-Graubard 95% confidence interval. |

| || Statistically significant difference compared with referent group. |

| ¶ Race/ethnicity was self-reported. Respondents identified as Hispanic might be of any race. The “Other” race category included Asians, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders, and women who selected “other” or multiple races. |

| ** Respondents were asked about their current work/volunteer activities. Those who reported being a healthcare worker working directly or not working directly with patients, frontline essential worker (not in healthcare), essential worker (not in healthcare and not frontline), or non-essential worker or volunteer were considered to be working. Respondents who indicated that they were not currently working or volunteering were considered to be not working. |

| †† Poverty status was defined based on the reported number of persons living in the household and annual household income, according to U.S. Census poverty thresholds. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html |

| ‡‡ Rurality was defined using ZIP codes where >50% of the population resides in a nonmetropolitan county, a rural U.S. Census tract, or both, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration’s definition of rural population. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html |

| §§ Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. |

| |||| Respondents pregnant on their survey date were asked what medical insurance or medical care coverage they had; respondents who had already delivered were asked what they had during their most recent pregnancy. Women considered to have public insurance selected at least one of the following: Medicaid, Medicare, state-sponsored medical plan, or other government plan. Respondents considered to have private/military insurance selected private medical insurance and/or military medical care and did not select any type of public insurance. |

| ¶¶ Estimates do not meet the NCHS standards of reliability. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_175.pdf |

| *** Respondents were asked, “Has your doctor, nurse, or another medical professional recommended that you get a COVID-19 vaccination?” |

| ††† For this analysis, conditions other than pregnancy that were included as those that could increase risk for serious medical complications of COVID-19 were asthma, chronic bronchitis or COPD, cancer, diabetes, heart attack/disease/condition, chronic liver disease, kidney disease, Down syndrome, weakened immune system from solid organ transplant or from blood or bone marrow transplant/immune deficiencies/HIV/use of corticosteroids or other immune weakening medicines, Sickle cell disease, obesity, neurological/neuromuscular conditions, or being a current smoker. Respondents missing information were excluded from analysis (n=13 in COVID-19 analysis, n=5 in COVID-19 booster analysis). Some conditions currently considered to be high risk for severe COVID-19 illness were not assessed by the survey. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html |

| ‡‡‡ Respondents were asked if they lived with anyone who had chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, chronic lung disease, asthma, a neurologic or neuromuscular disease, immune system problems, kidney disease, sickle cell disease, or hemophilia, or if they lived with anyone who was currently pregnant. |

| §§§ Receipt of influenza vaccination since July 1, 2021, before or during most recent pregnancy. |

| |||||| Timing of receipt of first/only dose of vaccine was calculated only among respondents who reported receiving at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine (n=825) and among those who had received a booster dose (n=237), as described above, with known timing. Timing of first dose of COVID-19 vaccine was missing for 25 respondents who skipped the questions on timing. Timing of booster dose was missing for 64 respondents due to the following: 1) 22 early responders encountered an erroneous skip pattern in the survey and were not asked about boosters, 2) 34 respondents we determined to receive a booster indicated that they had not received one so were not asked follow up questions such as timing, and 3) 8 respondents skipped the questions about timing; in addition, one respondent who received a booster during pregnancy was unsure about during which trimester.

¶¶¶ Suppressed to avoid risk of disclosure. |

Place of Flu (n=1,031), Tdap (n=362), First (or Only) COVID-19 (n=850), and COVID-19 Booster Vaccination (n=245) among Pregnant Women, United States, Internet Panel Survey, April 2022

- Place of booster dose was missing and excluded for 56 respondents due to the following: 1) 22 early responders encountered an erroneous skip pattern in the survey and were not asked about boosters, and 2) 34 respondents we determined to receive a booster indicated that they had not received one so were not asked follow-up questions such as place.

- “Other place” of vaccination includes other medically or non-medically related places, including a school or special site set up for COVID-19 vaccination.

References

- Grohskopf, L.A., et al., Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2022-23 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2022. 71(1): p. 1-28.

- Liang, J.L., et al., Prevention of Pertussis, Tetanus, and Diphtheria with Vaccines in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep, 2018. 67(2): p. 1-44.

- Havers, F.P., et al., Use of Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccines: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(3): p. 77-83.

- CDC. COVID-19 ACIP Vaccine Recommendations. 2022; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/covid-19.html.

- CDC. COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding. 2022; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/pregnancy.html.

- Kahn, K.E., et al., Flu and Tdap Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women – United States, April 2021. 2021; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/pregnant-women-apr2021.htm.

- Zambrano, L.D., et al., Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status – United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(44): p. 1641-1647.

- Allotey, J., et al., Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj, 2020. 370: p. m3320.

- Wei, S.Q., et al., The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cmaj, 2021. 193(16): p. E540-e548.

- Woodworth, K.R., et al., Birth and Infant Outcomes Following Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pregnancy – SET-NET, 16 Jurisdictions, March 29-October 14, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(44): p. 1635-1640.

- Lindley, M.C., et al., Vital Signs: Burden and Prevention of Influenza and Pertussis Among Pregnant Women and Infants – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2019. 68(40): p. 885-892.

- Razzaghi, H., et al., COVID-19 Vaccination and Intent Among Pregnant Women, United States, April 2021. Public Health Rep, 2022. 137(5): p. 988-999.

- Razzaghi, H., et al., COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among women aged 18-49 years by pregnancy status, United States, April-November 2021. Vaccine, 2022. 40(32): p. 4554-4563.

- Orenstein, W.A., et al., Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory committee: standards for adult immunization practice. Public Health Rep, 2014. 129(2): p. 115-23.

- O’Leary, S.T., et al., Immunization Practices of U.S. Obstetrician/Gynecologists for Pregnant Patients. Am J Prev Med, 2018. 54(2): p. 205-213.

- ACOG. Immunization for Women, Physician Tools. 2021 [cited 2021 08/23/2021]; Available from: https://www.acog.org/programs/immunization-for-women/physician-tools?utm_source=redirect&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=int.

- Kahn, K.E., H. Razzaghi, and K.H. Nguyen, Prevalence of maternal vaccine hesitancy in the United States, and association with maternal influenza and Tdap vaccination uptake, 2019–20 and 2020–21 influenza seasons. in CityMatCH Leadership and MCH Epidemiology Conference. 2021. Virtual.

- Kahn, K.E., et al., Influenza and Tdap Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women – United States, April 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2018. 67(38): p. 1055-1059.

- Nunes, M.C. and S.A. Madhi, Influenza vaccination during pregnancy for prevention of influenza confirmed illness in the infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2018. 14(3): p. 758-766.

- Prasad, S., et al., Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 2414.

- Razzaghi, H., et al., Influenza and Tdap Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women – United States, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020. 69(39): p. 1391-1397.

- Brewer, L.I., et al., Structural inequities in seasonal influenza vaccination rates. BMC Public Health, 2021. 21(1): p. 1166.

- Lu, P.J., et al., Trends in racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination coverage among adults during the 2007-08 through 2011-12 seasons. Am J Infect Control, 2014. 42(7): p. 763-9.

- Uscher-Pines, L., J. Maurer, and K.M. Harris, Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Uptake and Location of Vaccination for 2009-H1N1 and Seasonal Influenza. American Journal of Public Health, 2011. 101(7): p. 1252-1255.

- CDC. CovidVaxView Interactive. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Vaccine Confidence Among Adults. 2022; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/covidvaxview/interactive/adults.html.

- Kriss, J.L., et al., Intent to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine and Behavioral and Social Drivers of Vaccination by Race and Ethnicity, National Immunization Survey Adult COVID Module — United States, October 31–December 31, 2021. 2022; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/covidvaxview/pubs-resources/intent-receive-covid19-vaccine-behavioral-social-drivers.html.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. 2022; Available from: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/dashboard/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-dashboard/.

- Razzaghi, H., et al., Receipt of COVID-19 Booster Dose Among Fully Vaccinated Pregnant Individuals Aged 18 to 49 Years by Key Demographics. Jama, 2022. 327(23): p. 2351-2354.

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. 2016 [cited 2021 08/23/2021]; Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination.

- Galea, S., S. Sisco, and D. Vlahov, Reducing disparities in vaccination rates between different racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups: the potential of community-based multilevel interventions. J Ambul Care Manage, 2005. 28(1): p. 49-59.

- Jarrett, C., et al., Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy – A systematic review. Vaccine, 2015. 33(34): p. 4180-90.

- Office of Minority Health. Immunizations and American Indians/Alaska Natives. 2020 [cited 2021 09/28/2021]; Available from: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlID=37.

- APORR, AAPOR Guidance on Reporting Precision for Nonprobability Samples. 2015.