Flu Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women – United States, 2015-16 Flu Season

Pregnant women and infants are at increased risk for complications and hospitalization from influenza (flu). Flu vaccination can reduce the risk of flu-related illness for pregnant women and their infants (1). Since 2004, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended flu vaccination for all women who are or will be pregnant during the flu season, regardless of trimester (1).

To assess flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women during the 2015–16 flu season, CDC analyzed data from an Internet panel survey conducted during March 29–April 7, 2016. This report provides end of flu season estimates of vaccine uptake by pregnant women for 2015-16 flu season. Differences of at least five percentage points between estimates are noted (please see below for details of the methodology).

Key Findings

- As of early April 2016, flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women (before and during pregnancy) was 49.9%.

- 14.1% were vaccinated before pregnancy and 35.8% were vaccinated during pregnancy.

- The overall vaccination coverage was similar to that in the 2014-15 (50.3%), 2013–14 (52.2%) and 2012–13 (50.5%) flu seasons, but higher than that in the 2010–11 season (44.0%).

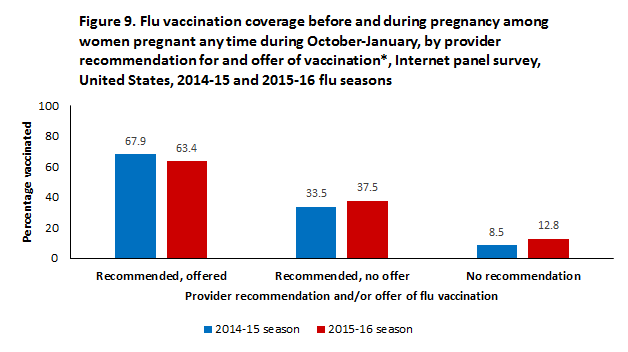

- Most pregnant women (99.4%) reported visiting a doctor or other medical professional at least once since July 1, 2015; among these women, 67.6% reported receiving a recommendation for and offer of vaccination from a doctor or other medical professional, 12.5% received only a recommendation for and no offer of vaccination, and 19.9% did not receive a recommendation for flu vaccination.

- The proportion of pregnant women who reported receiving a provider recommendation and offer of vaccination was similar to the past three seasons.

- Pregnant women who received a recommendation for and an offer of vaccination from a doctor or other medical professional were more likely to be vaccinated compared with women who received only a recommendation but no offer, or received no recommendation.

- Self-reported vaccination coverage among these women was 63.4%, 37.5%, and 12.8%, respectively.

Conclusion/Recommendation:

Implementing the Standards for Adult Immunization Practice (3), which state that all health care providers should assess, recommend, administer or refer, and document vaccinations, can reduce missed opportunities for vaccination and increase vaccination coverage among pregnant women.

Who Was Vaccinated?

- Coverage by Health Care Provider Recommendation and Offer

- Coverage by Attitude Toward Effectiveness of Flu Vaccination

- Coverage by Attitude Toward Safety of Flu Vaccination

- Coverage by Attitude Toward Flu Infection

- Place of Vaccination

- Main Reason for Receiving Vaccination

- Main Reason for Not Receiving Vaccination

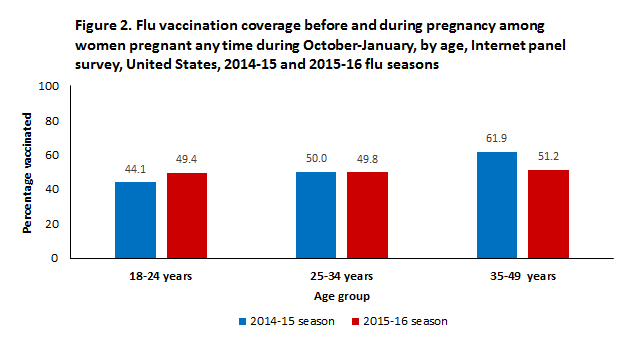

Coverage by Age Group

- There were no differences in vaccination coverage by age in the 2015-16 flu season.

- Vaccination coverage among pregnant women 18-24 years increased from 44.1% in the 2014-15 season to 49.4% in the 2015-16 season, and coverage among women 35-49 years decreased from 61.9% in 2014-15 to 51.2% in 2015-16 among women 35-49 years. Coverage was similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16 among women 25-34 years.

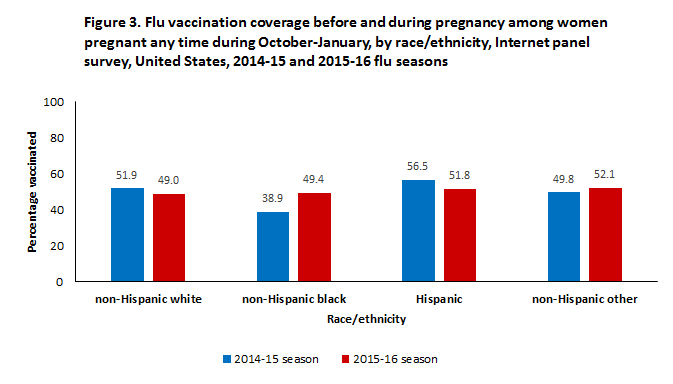

Coverage by Race/Ethnicity

- There were no differences in vaccination coverage by race/ethnicity in the 2015-16 flu season.

- Vaccination coverage among pregnant black women increased from 38.9% in the 2014-15 season to 49.4% in the 2015-16 season. Coverage was similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16 among women in all other racial/ethnic groups.

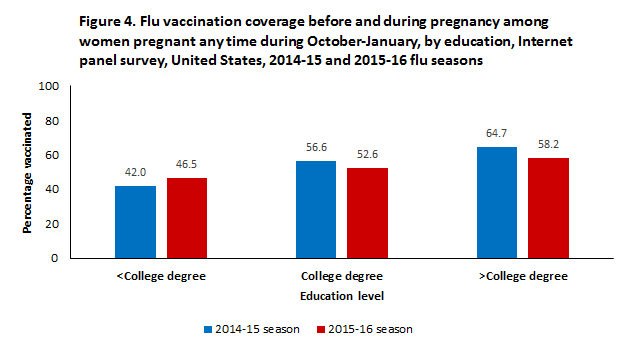

Coverage by Education

- In the 2015-16 flu season, vaccination coverage was lowest among pregnant women with less than a college degree (46.5%) and higher among women with a college degree (52.6%) or more than a college degree (58.2%).

- Vaccination coverage among women with more than a college degree decreased from 64.7% in 2014-15 to 58.2% in 2015-16. Vaccination coverage among women in all other education categories was similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16.

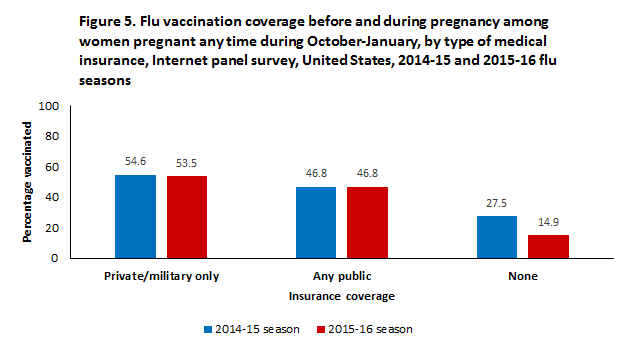

Coverage by Type of Medical Insurance

- In the 2015-16 flu season, pregnant women who reported having only private (including military) insurance during pregnancy had higher vaccination coverage (53.5%) than pregnant women who reported having any type of public medical insurance (46.8%) and those who reported not having insurance (14.9%).

- Vaccination coverage among women without medical insurance decreased from 27.5% in 2014-15 to 14.9% in 2015-16. Coverage among women with private and public insurance was similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16

- Very few pregnant women reported not having medical insurance (approximately 2% in 2015-16).

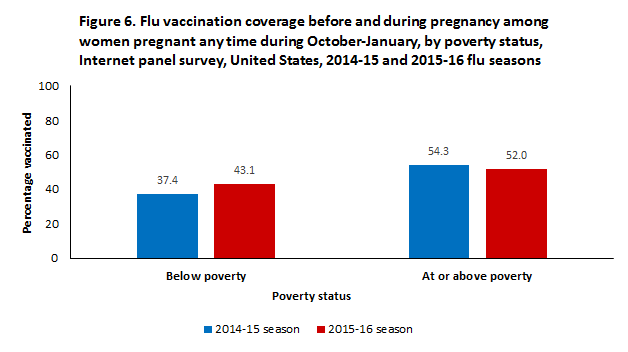

Coverage by Poverty Status

- In the 2015-16 flu season, pregnant women living at or above poverty had higher vaccination coverage (52.0%) compared with women living below the poverty level (43.1%).

- Vaccination coverage among women below the poverty level increased from 37.4% in 2014-15 to 43.1% in 2015-16.

Coverage by Other High-Risk Conditions‡

- In the 2015-16 flu season, pregnant women with a high-risk condition (in addition to pregnancy) that increases the risk of severe flu had higher vaccination coverage (55.6%) than women with no additional high-risk conditions (45.7%).

- These results were similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16.

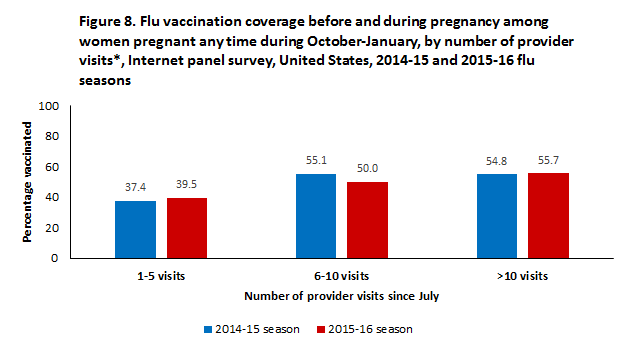

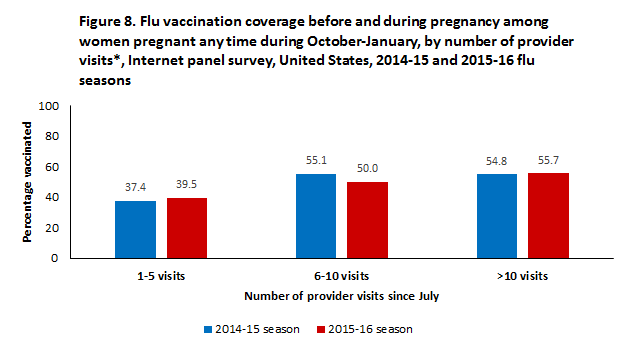

Coverage by Number of Provider Visits Since July*

- In the 2015-16 flu season, pregnant women with more than 10 visits to a medical provider since July 2015 had higher vaccination coverage (55.7%) compared with women who had 6-10 visits (50.0%) and 1-5 visits (39.5%).

- Vaccination coverage among women with 6-10 provider visits decreased from 55.1% in 2014-15 to 50.0% in 2015-16

Coverage by Health Care Provider Recommendation and Offer*

- Most pregnant women (99.4%) reported visiting a doctor or other medical professional at least once since July 1, 2015; among these women, 67.6% reported receiving a recommendation for and offer of flu vaccination from a doctor or other medical professional, 12.5% received only a recommendation but were not offered the vaccine, and 19.9% did not receive a recommendation for flu vaccination. These results were similar to the 2014-15 flu season. ( Table 1 [245 KB, 3 pages] )

- In the 2015-16 season, flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women was highest (63.4%) among women who reported their doctor or other medical professional recommended and offered the vaccination.

- 37.5% of pregnant women were vaccinated among those that reported they received only a recommendation for but no offer of vaccination from their doctor or other medical professional.

- Only 12.8% of pregnant women were vaccinated among those that reported they did not receive a recommendation for vaccination from their doctor or other medical professional.

- Of the women in the 2015-16 season who reported that their provider recommended but did not offer vaccination, 50.9% received a referral§ to go someplace else to get the vaccination.

- Of these women referred elsewhere, 47.3% were vaccinated compared with 27.3% of women who received a provider recommendation but no referral.

- The relationship between vaccination coverage among pregnant women and receipt of a health care provider recommendation for and offer of flu vaccination was similar in the 2015-16 season compared with the 2014-15 season.

- The percentage of pregnant women who received a provider recommendation or offer of vaccination [233 KB, 3 pages] varied by demographic characteristics.

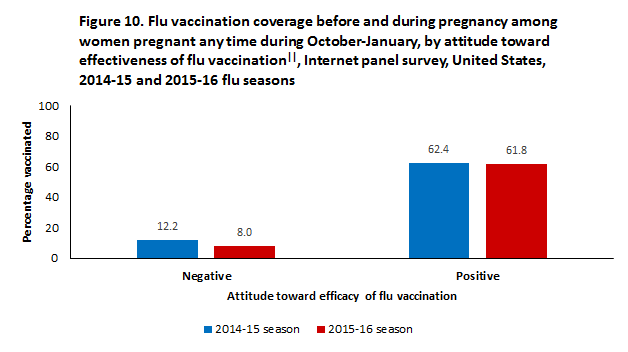

Coverage by Attitude Toward Effectiveness of Flu Vaccination||

- In the 2015-16 flu season, pregnant women with a positive attitude toward the effectiveness of flu vaccination had higher vaccination coverage (61.8%) than women with a negative attitude toward the effectiveness of flu vaccination (8.0%).

- These results were similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16.

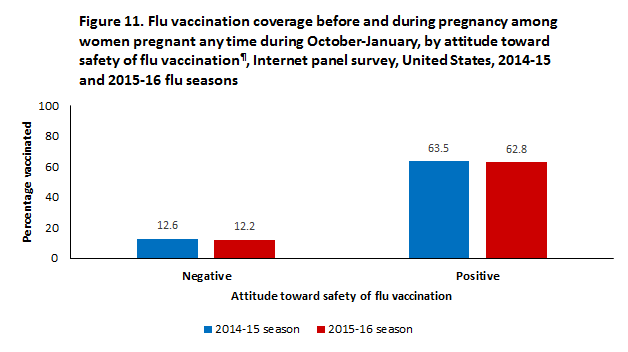

Coverage by Attitude Toward Safety of Flu Vaccination¶

- In the 2015-16 flu season, pregnant women with a positive attitude toward the safety of flu vaccination had higher vaccination coverage (62.8%) than women with a negative attitude toward the safety of flu vaccination (12.2%).

- These results were similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16.

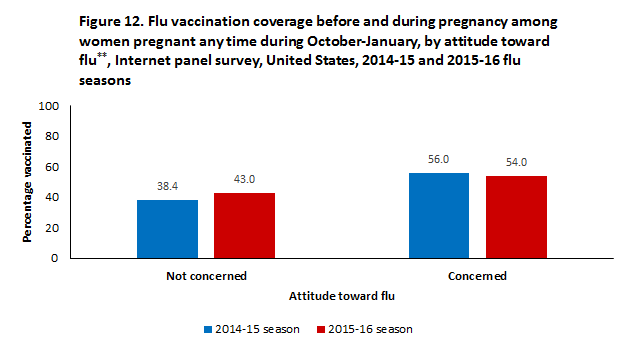

Coverage by Attitude Toward Flu Infection**

- In the 2015-16 flu season, pregnant women who were concerned about flu inflection had higher vaccination coverage (54.0%) than women who were not concerned about flu infection (43.0%).

- These results were similar in 2014-15 and 2015-16.

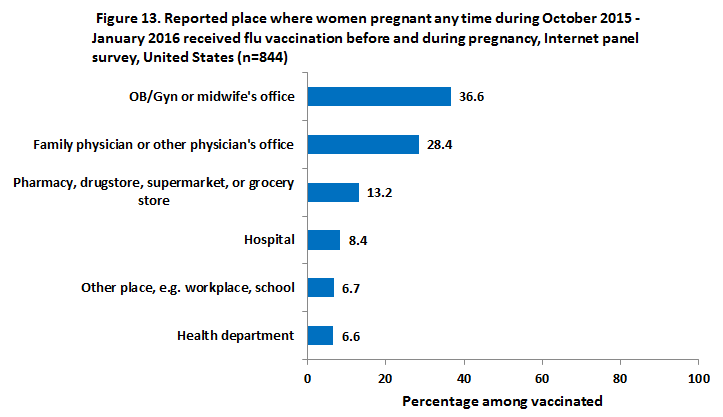

Place of Vaccination

- The most commonly reported places for receiving flu vaccination among pregnant women in the 2015-16 flu season were in the office of an obstetrician/gynecologist or midwife (36.6%) or family physician or other physician (28.4%).

- 13.2% of pregnant women were vaccinated in a pharmacy or store.

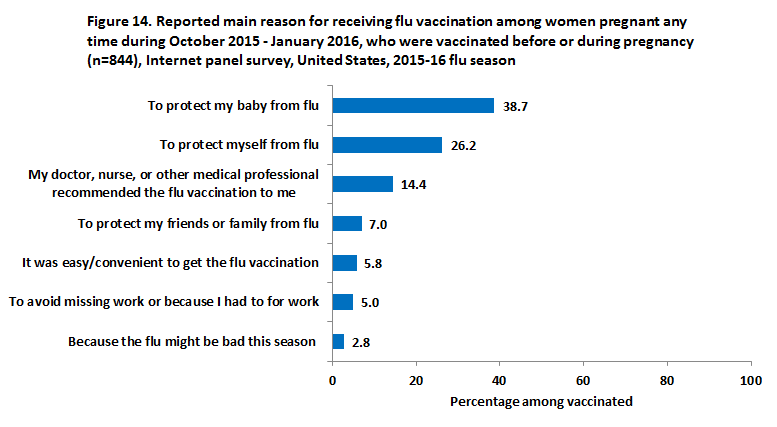

Main Reason for Receiving Vaccination

- The most common main reason reported by pregnant women for receiving a flu shot was to protect their baby from flu (38.7%).

- The second most commonly reported main reason was to protect herself from flu (26.2%).

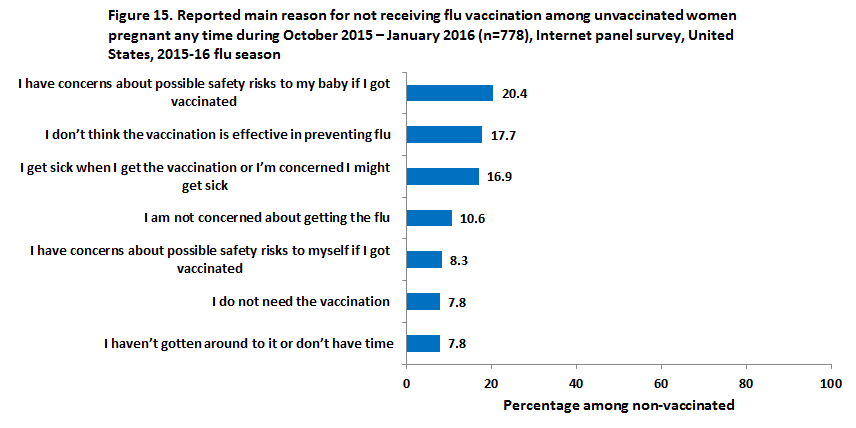

Main Reason for Not Receiving Vaccination

- The most common main reason reported by pregnant women for not receiving a flu shot was concern about possible safety risks to their baby if they got vaccinated (20.4%).

- The second and third most commonly reported main reasons for not receiving a flu shot were belief that the vaccine was not effective in preventing the flu (17.7%) and concern about getting sick from the flu vaccine (16.9%).

- Barriers to vaccination access, such as lack of medical insurance or cost, unavailability of the vaccine, and lack of knowledge regarding where to get the vaccine were rarely reported as a main reason for not receiving a flu shot.

What can be done?

During the 2015–16 flu season, flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women remained stable at approximately 50% compared with the previous four seasons. Although the Standards for Adult Immunization Practice (3) support recommendation and offer of flu vaccination, the percentage of women who reported receiving a provider offer and recommendation has not increased in the last three flu seasons. This might be partly attributable to differences in the perception of what constitutes a recommendation for vaccination between patients and providers. In a recent survey of obstetric care providers conducted by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, all surveyed providers reported that they recommend flu vaccine to their pregnant patients, compared with 85% of patients surveyed at the same practices who reported receiving a recommendation for vaccination (4). Additionally, obstetric providers have reported barriers to vaccinating adult patients, most notably the costs associated with stocking vaccines, lack of time and lack of patient interest (5).

Findings in this report indicate that a provider’s recommendation and offer of flu vaccination to pregnant patients is associated with higher rates of patients receiving flu vaccination. However, prevalence of provider recommending and offering flu vaccination to pregnant women has not increased over the past three flu seasons. Missed opportunities for provider recommendations can be reduced by implementing provider reminders and standing orders for vaccination to ensure that flu vaccination is recommended and offered at each visit before and during pregnancy (6,7). Also, among women who were not offered vaccination, those who were referred to another provider were more likely to be vaccinated than women who received a recommendation without an offer or referral for vaccination. The National Vaccine Advisory Committee’s Standards for Adult Immunization Practices include guidance for all providers to strongly recommend needed vaccines and either administer vaccines or refer patients to a provider who can immunize (3). Fully implementing these standards in health care settings serving pregnant women could increase flu vaccination coverage, protecting both the mother and the infant.

There were no reported differences in vaccination coverage by race/ethnicity in the 2015-16 flu season. In previous seasons, non-Hispanic black women consistently had lower vaccination coverage compared with non-Hispanic white women, despite similar percentages of black and white women reporting a provider recommendation and offer of vaccination (2). Prior studies have found that the long-standing lower coverage among non-Hispanic black women might be due to weaker or less effective provider recommendations, differences in sociocultural norms, misperception of effectiveness and safety of vaccination, and vaccination resistance and hesitancy (8,9). Future rounds of this survey will provide information as to whether the closing of this gap is sustained.

Continued efforts are needed to improve flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women, including:

Increasing the proportion of pregnant women who receive a recommendation for and offer of flu vaccination from their doctor or other medical professional:

- Implementing and strengthening the systems that support provider ability to recommend and offer vaccination to pregnant women:

- Standing orders;

- Provider reminder systems;

- Expanded access to vaccination services in multiple health care settings (e.g., pharmacies).

Health care providers should inform pregnant women about the risk of flu infection for them and their babies and about the benefits and risks of flu vaccination:

- Health care providers and immunization programs should provide pregnant women with accurate information on the following topics:

- The risk of the flu and related complications, including hospitalization and death, for pregnant women and their babies;

- The benefits and risks of flu vaccination for mothers and their babies;

- The protection transferred to unborn babies by vaccination during pregnancy, since infants younger than 6 months old cannot be vaccinated themselves.

- Clinic-based education for patients in combination with standing orders and provider reminders can increase vaccination coverage(6).

- Clinic-based education can be supplemented by increasing patient awareness with messages delivered through social media and text messaging (e.g. https://text4baby.org).

- Related resources:

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Flu shot for pregnant patients: frequently asked questions. 2013. [970 KB, 2 pages]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Physician script on influenza immunization during pregnancy. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013. [946 KB, 2 pages]

- CDC. Pregnant Women and Influenza (Flu).

- CDC. Pregnant Women Need a Flu Shot. [780 KB, 2 pages]

- CDC. Questions and Answers About Vaccines During Pregnancy…

- CDC. Information for Health Professionals.

- Text4baby. Texts to keep you and baby healthy.

Data Sources and Methods

The Internet panel survey was conducted for CDC by Abt Associates, Inc. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) during March 29 – April 7, 2016 to 1) provide end-of-season estimates of flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women for the 2015–16 flu season; 2) assess respondent-reported provider recommendation and offer of flu vaccination; and 3) obtain updated information on pregnant women’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to flu vaccination. Women aged 18–49 years who reported being pregnant at any time since August 1, 2015 through the date of the survey were eligible to participate. Participants were recruited from a pre-existing, national, opt-in, general population Internet panel operated by Survey Sampling International, which provides panel members with online survey opportunities in exchange for nominal incentives.†† Pregnant women panelists were recruited using two methods: 1) an email invitation was sent to female panel members aged 18–49 years living in the United States and 2) a message on the panel website invited panel members to answer a series of screening questions and, if eligible, to take the survey. Of 10,667 women who entered the survey site, 2,201 were determined to be eligible and 2,104 completed the survey (a cooperation rate of 95.6%).‡‡ Data were weighted to reflect the age, race/ethnicity, and geographic distribution of the total U.S. pregnant women population. The analysis was limited to the 1,692 women who reported being pregnant any time during the peak flu vaccination period (October 2015–January 2016). A woman was considered to be vaccinated if 1) vaccination was received during July 1, 2015–April 6, 2016 and 2) vaccination was received before or during the most recent pregnancy. Vaccination coverage estimates from Internet panel surveys conducted during the preceding five seasons were compared to assess trends over time. Similar survey methodology was used in all six seasons (2).

Survey respondents were asked about their vaccination status, whether their provider recommended and/or offered flu vaccination, their attitudes regarding flu and flu vaccination, and their reasons for receiving or not receiving flu vaccination. Because the opt-in Internet panel sample is not probability-based, no statistical tests were performed.§§ A difference was noted as an increase or decrease when there was a ≥5 percentage-point difference between any values being compared.

Sample demographics

A total of 1,692 women pregnant any time during October 1, 2015-January 31, 2016 were included in the 2015-16 season survey, and a total of 1,702 women pregnant any time during October 1, 2014-January 31, 2015 were included in the 2014-15 season survey. Sample sizes by demographic characteristics, along with additional information about flu vaccination coverage by demographic characteristics, are given in Table 1 [245 KB, 3 pages].

Limitations

The findings in the report are subject to several limitations:

- Vaccination was self-reported and not validated by medical record review.

- The study sample did not include women without Internet access. Therefore, results might not be generalizable to all pregnant women in the United States.

- Estimates might be biased if a woman’s decision to join the Internet panel or participate in this particular survey were related to receipt of vaccination.

- The composite variables computed for attitudes toward flu vaccination and infection were not validated.

Despite these limitations, the opt-in Internet panel survey provides timely estimates of flu vaccination coverage and in-depth information about knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and barriers related to flu vaccination among pregnant women. Trends in vaccination coverage reported from the Internet panel surveys have been consistent with those reported from less timely probability sampling surveys (10).

Authors

Helen Ding, MD1,MSPH ; Carla L. Black, PhD2; Sarah Ball, ScD3; Sara Donahue, DrPH3; Rebecca V. Fink, MPH3;Walter W. Williams, MD, MPH2; Amy Parker Fiebelkorn, MSN, MPH2; Peng-Jun Lu, MD, PhD2; Katherine E. Kahn, MPH4; Denise D’Angelo, MPH5; Indu B. Ahluwalia, PhD6; Rebecca Devlin, MA7; Charles DiSogra, DrPH7; Deborah K. Walker, EdD3; Stacie M. Greby, DVM, MPH2

1CFD Research Corporation, Huntsville, AL;

2Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC;

3Abt Associates, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts;

4Leidos, Atlanta, GA; CDC;

5Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC;

6Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 7Abt SRBI, New York, New York

(Corresponding author: Helen Ding, hding@cdc.gov, 404-639-8513)

Related Links

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Flu shot for pregnant patients: frequently asked questions. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013.

- CDC. Standards for Adults Immunization Practice. 2016.

- CDC. FluVaxView: Influenza vaccination coverage. 2016.

- CDC. Pregnant Women and Flu Vaccination, Internet Panel Survey, United States, November 2015. 2016.

- CDC. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women — United States, 2014–15 Influenza Season. 2015.

- CDC. Pregnant Women and Flu Vaccination, Internet Panel Survey, United States, November 2014. 2014.

- CDC. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women — United States, 2013–14 Influenza Season. 2014.

- CDC. Pregnant Women and Flu Vaccination, Internet Panel Survey, United States, November 2013. 2013.

- CDC. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women — United States, 2012–13 Influenza Season. 2013.

- CDC. Pregnant Women and Flu Shots, Internet Panel Survey, United States, November 2012. 2012.

- CDC. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women — 2011–12 Influenza Season, United States. 2012.

- CDC. Pregnant Women and Flu Shots, Internet Panel Survey, United States November 2011. 2011.

- CDC. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women — United States, 2010–11 Influenza Season. 2011.

- 2010-2011 early season online report for vaccination coverage among pregnant women. [427 KB, 6 pages]

- AAPS. Flu Vaccine Accepted by Pregnant Women, Not Linked to Miscarriage. 2011.

- CDC. PRAMS: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System.

- CDC. Prevention and Control of Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2015–16 Influenza Season

- Text4Baby

- SSI: Survey Sampling International

- SurveySpot

- Follow CDC Flu on Twitter: @CDCFlu

References

1. CDC. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), United States, 2013–14. MMWR 2013; 62(No. RR-07).

2. Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, 2014–15, Influenza season. MMWR 2015;64:1000-5.

3. National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: Standards for Adult Immunization Practice. Public Health Rep 2014;129:115-23.

4. Stark LM, Power ML, Turrentine M, et al. Influenza vaccination among pregnant women: patient beliefs and medical provider practices. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016;2016(ID#3281975):1-8.

5. Jones KM, Carroll S, Hawks D, McElwain CA, Schulkin J. Efforts to improve immunization coverage during pregnancy among ob-gyns. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016;2016(ID #6120701):1-9.

6. The Guide to Community Preventive Services: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/healthsysteminterventions.html. Accessed August 8, 2016.

7. Mazzoni SE, Brewer SE, Pyrzanowski JL, et al. Effect of a multi-modal intervention on immunization rates in obstetrics and gynecology clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 241; 617.e1-7.

8. Lindley MC, Wortley PM, Winston CA, Bardenheier BH. The role of attitudes in understanding disparities in adult influenza vaccination. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:281-5.

9. Fiscella K. Anatomy of racial disparity in influenza vaccination. Health Serv Res 2005;40:539-49.

10. CDC. Surveillance of influenza vaccination coverage—United States, 2007–2008 through 2011–12 influenza seasons. MMWR 2013;62(No. SS-04).

Footnotes

*Among women who reported having at least one visit to a provider since July.

†Vaccination coverage estimates for the 2012-13 through 2015-16 flu seasons were based on vaccination given from July to mid-April; coverage estimates for 2010-11 and 2011-12 flu season were based on vaccination given from August to mid-April.

‡Conditions associated with increased risk for serious medical complications from flu, including chronic asthma, a lung condition other than asthma, a heart condition, diabetes, a kidney condition, a liver condition, obesity, or a weakened immune system caused by a chronic illness or by medicines taken for a chronic illness.

§Referral is defined based on a “yes” response to the question “Did any doctor, nurse, or medical professional suggest that you go someplace else to get the flu vaccination?”

||Created based on two questions regarding attitudes toward the effectiveness of flu vaccination: 1) “Flu vaccine is somewhat/very effective in preventing flu,” and 2) “Flu vaccine a pregnant women received is somewhat/very effective in protecting her baby from the flu.” A 1-point score was given for each “yes” answer for either of the two questions. “Positive” attitude = summary score of 1 or 2; “negative” attitude = summary score of 0.

¶Created based on three questions regarding attitudes toward the safety of flu vaccination: 1)”Flu vaccination is somewhat/very/completely safe for most adult women”; 2) “Flu vaccination is somewhat/very/completely safe for pregnant women”; and 3) “Flu vaccination that a pregnant woman receives is somewhat/very/completely safe for her baby.” 1 point was given for each “yes” answer for any of the 3 questions. “Positive attitude” = summary score of 2 or 3; “negative attitude” = summary score of 0 or 1.

**Created based on three questions regarding attitude toward flu 1) “If a pregnant woman gets the flu, it is somewhat/very likely to harm the baby”; 2) “Flu infection during pregnancy somewhat/very likely harms pregnant women”; and 3) “somewhat/very worried about getting sick with the flu this season .” 1 point was given for each “yes” answer for any of the 3 questions. “Concerned” = summary score of 2 or 3; “Not concerned” = summary score of 1 or 0.

††Additional information on the online survey and incentives for participants is available at: http://www.surveysampling.com.

‡‡An opt-in Internet panel survey is a nonprobability sampling survey. The denominator for a response rate calculation cannot be determined because no sampling frame with a selection probability is involved at the recruitment stage. Instead, the survey cooperation rate is provided.

§§Additional information on obstacles to inference in non-probability samples is available at: Report of the AAPOR Task Force On Non-probability Sampling.