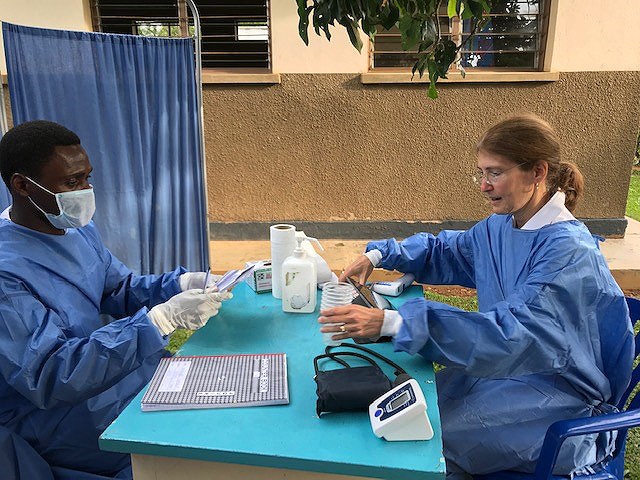

Long flights, long days mark vaccine campaign

CDC’s Rosalind Carter, right, and a Ugandan colleague prepare to give the Ebola vaccine to health workers in northwestern Uganda in July 2019.

Since the current outbreak of Ebola emerged in August 2018, nearly 400 CDC volunteers have deployed to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), neighboring countries, and Geneva to help fight the disease.

Some have deployed three, four, or a half-dozen times.

And then there’s Rosalind Carter, an epidemiologist and one of CDC’s leading vaccine experts. Carter has packed her bags and taken off 12 times so far, making her the response’s most frequent flyer.

“It sounds very elegant to be going all around the world saving lives, but the actual day-to-day is pretty physically demanding,” she says. “Even if you’re sitting in meetings, it’s mentally and emotionally draining, especially if the work requires delicate diplomacy.”

Carter has been advising preventive vaccination campaigns in the DRC’s neighboring countries of Uganda and South Sudan, preparing them for the chance that Ebola might slip across the borders of the DRC. The work is aimed at doctors, nurses, and other frontline healthcare workers who might be exposed to the virus while treating patients.

In those deployments, Carter built trust between CDC and its partner agencies, including the World Health Organization and the health ministries in Uganda and South Sudan. She built relationships and ensured continuity as they rolled out vaccination campaigns to prepare for possible introduction of the disease.

“The team members continued to innovate and improve vaccine delivery to the point where I was learning from them on subsequent deployments,” she says. “I could not have been more proud.”

That preparation was put to the test last summer, when a sick child crossed into Uganda with relatives from the DRC. Three cases were identified among the family, and Ugandan authorities worked quickly to vaccinate the sick people’s contacts and people those contacts had encountered.

“The fact that the Ugandan teams had already vaccinated 5,000 healthcare workers made all the difference in quickly being able to shift gears and take the same skills and now apply them to a different population,” Carter says.

After logging nearly 200 deployment days overseas, Carter says her family—a husband and three grown children—are “less patient than they were” at the outset. But she’s learned to balance the deployments with planned vacation time afterwards, which helps her reconnect with her family when she returns.

In Africa, the work means a lot of early mornings and late nights. There’s often a long drive to wherever the vaccinations are taking place, setting up a workstation, and giving shots from 8 am to 6 pm.

After the drive back, there’s a meeting to discuss the next day’s plans and a call back to headquarters in Atlanta. Lunch breaks can be rare, so bringing food is essential, she says.

“Some of the most precious moments have been with the local staff, sharing their snacks,” Carter says. “I swear by instant coffee or bringing ground coffee in a portable French press. That’s my most important travel companion.”

She also has developed a fondness for dressing like a local. Not only is it more practical for the warm climate, it’s an icebreaker.

“I’m always going to stand out because of what I look like. But people are intrigued that I wear local clothes, and it gives us something to talk about,” Carter says. “I’ve had a lot of opportunity to observe beautiful fabrics and different styles. I love going to fabric markets.”

Her interest in public health emerged as she was preparing for medical school. She studied social science, biology, and statistics as an undergraduate—then took a course on epidemiology, “and decided that was all of my favorite things in one place.” She decided to focus on that discipline instead, earned a PhD and joined the “disease detectives” of CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service in 1994.

Carter was assigned to the New York City Health Department at the height of the AIDS epidemic, when treatments were still developing. Some of the people she worked with were infected or dying, and Carter says the experience taught her to see the humanity behind the statistics.

“Each case was a person with a family and a unique outlook on life,” she says. “You could never forget that every data point on a graph represented a person.”

That’s true of Ebola as well, Carter adds.

“Behind the bar charts, I can picture so many of the thousands of doctors, nurses, and cleaners we vaccinated,” she says. “I remember the stories they told me about previous Ebola outbreaks and why they were motivated to take a vaccine that was now available to them.”