Ebola outbreak becomes a “class” act for EIS officers

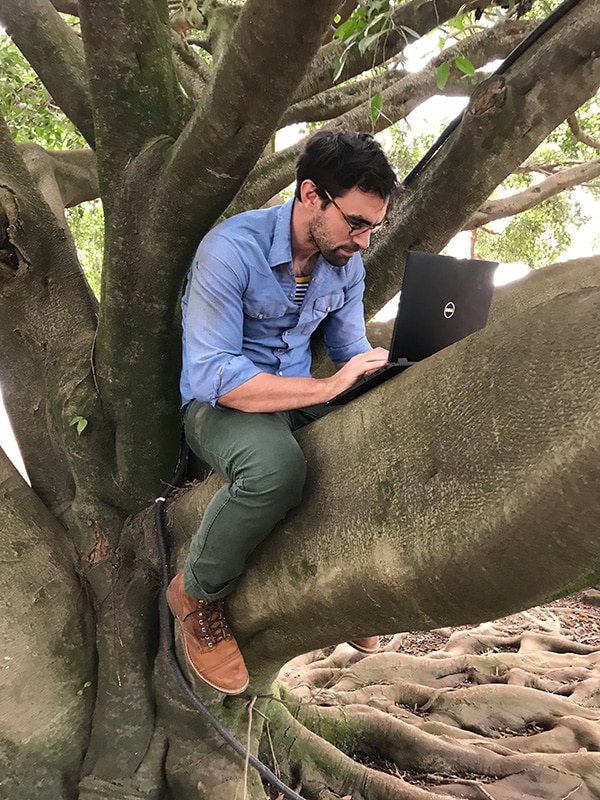

EIS Officer Dean Sayre finds an alternative workspace outside the CDC office in Goma during his July-August deployment to the DRC

Credit: Nathan Furukawa, CDC

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the “disease detectives” of CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) are proving their worth as they work to stop the second-largest Ebola outbreak in history.

EIS officers spend two years on the front lines of public health to protect Americans and the global community. As part of their service fellowship, they get on-the-job training with seasoned veterans while working to identify and control a disease outbreak and recommend practical approaches to prevent future epidemics.

Of the 131 current EIS officers, 33 have volunteered to support CDC’s response in the DRC and neighboring countries thus far. They work hard to prevent travelers from spreading Ebola, to keep it from gaining a foothold in healthcare facilities, and track down the contacts of people who have contracted the disease.

“Even though there were a lot of things that were challenging about it, it was a pretty valuable experience to have,” says Dean Sayre, of the EIS Class of 2018, who returned from the DRC in September 2019.

EIS officers helped eliminate smallpox in the 1970s, fought the first known Ebola outbreak in 1976 and helped probe the anthrax attacks in 2001. More than 3,600 have served in the globally recognized program since it began in 1951.

“From the moment CDC announced it was scaling up a workforce to support the Ebola response in the DRC, we had EIS officers lining up at the door asking how they could get out and contribute,” says Public Health Service CAPT Eric Pevzner, chief of the EIS. “We’re always fortunate in that we attract really exceptional, bright, dedicated people committed to service so when we have these really challenging situations, the EIS officers are often the first to volunteer and be deployed.”

Sayre’s 2018 classmate Nirma Bustamante came to the EIS after working as an emergency medicine physician specializing in humanitarian emergencies, including working with Syrian refugees at a camp in Greece. “I don’t think I ever could have imagined a more incredible or more meaningful public health experience,” she says. “I’ve been very fortunate to have an incredible experience internationally, but this has been by far one of the more intensive, complex and intriguing experiences I’ve had.”

In three deployments so far, Bustamante has helped set up the CDC’s response headquarters in Goma, worked with the World Health Organization in Geneva and tracked Ebola cases in a remote mountain village. The day she arrived in Goma on her second deployment over the summer was the same day a second case of Ebola had been confirmed in that major regional hub.

“We went straight to the WHO office and stayed until 1 am, and the next morning we were out in the field, setting up vaccination sites with the team,” she says. “We hit the ground running.”

Sayre traces interest in the field to a medical school class on population health—a big-picture field that looks at patterns of illness in large groups of people. “I remember sitting in the back of the class and wondering how the lecturer got that job,” he says. “It seemed like the coolest job and coolest way to use their medical training and look at some of these bigger issues.”

Sayre specialized in pathology during his residency, “but you don’t necessarily get that gratification of being on the front lines.” So when one of his supervisors recommended EIS, “it just seemed to click.”

“It was essentially the work that I always wanted to do, but I didn’t know the role existed,” he says.

After going back to school for a master’s in epidemiology, Sayre applied for EIS and was assigned to the CDC division that fights malaria. When the current Ebola outbreak emerged, he had experience working in Africa and spoke French, so he decided to volunteer.

In the DRC, he found himself working alongside responders from the WHO and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, poring over data on cases, contacts and deaths. Those statistics revealed gaps that needed to be addressed to help Congolese health authorities stop the epidemic. He says he “learned a ton” of new tricks from the experience.

EIS Officer Nirma Bustamante on a trip to trace contacts of an Ebola patient in the village of Chowe, south of Goma, in August.

Credit: Nirma Bustamante, CDC

“It’s a challenge to make sure we have reliable data while we’re there,” he says. But he adds, “Everyone has something to add, and a lot of things these different organizations can add is valuable.”

Nearly every EIS class has faced some defining event right out of the gate, Pevzner says. For his 2005 cohort, it was Hurricane Katrina. During the West Africa Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016, all 158 officers at the time were deployed at some point, “some of them many times over.” EIS grads in 2016 also found themselves on the front lines of the investigation and response to the Zika virus epidemic in Latin America and the Caribbean.

But the classes of 2018—and now, 2019—are involved in a number of high-profile responses. Besides Ebola, they’re investigating new measles outbreaks and lung injuries from use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products; deploying to support the Polio eradication efforts; and helping with the response to the ongoing epidemic of opioid drug related deaths.

“I’ll be interested to see how they’re remembered considering they’re responding to so many high-profile and really complicated public health issues at once,” Pevzner says. “But certainly, they’ll be remembered for their willingness to volunteer and be of service to the agency and all our partners in addressing a number of important and memorable public health challenges.”