Unfair and Unjust Practices and Conditions Harm Hispanic and Latino People and Drive Health Disparities

Some U.S. historical policies and practices have led to mental and physical health risks and challenges, and related long-term health outcomes, for Hispanic/Latino people. For example:

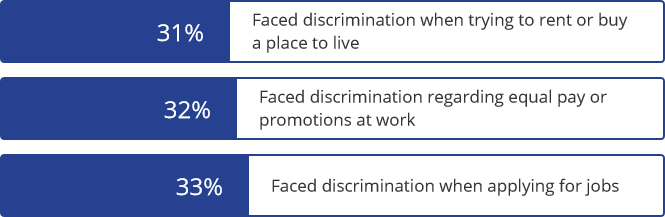

Historically, Hispanic/Latino people in the U.S. have faced racial, ethnic, and anti-immigrant prejudice, including discrimination in employment, housing, and education.13 Acts of violence and hate crimes have also caused injuries and deaths among Hispanic/Latino people in the U.S. 14,15

Hispanic/Latino people have also experienced discrimination and harm from systems meant to protect and improve health and well-being. Some examples of historical policies and practices that have important implications for the mental and physical health of Hispanic population groups include:

- State and federal programs in the 1920s sought to change diets of Mexican American families in the U.S. based on the mistaken belief that traditional Mexican foods were less nutritious than standard American diets.16 This resulted in negative effects on Mexican American health. Today, children of Mexican origin in the U.S. are more likely to experience obesity than other children in the U.S. and children who live in Mexico.17

- Harm and uneven treatment from healthcare systems, such as the sterilization of Hispanic/Latino women without their permission, leading to a mistrust of healthcare systems and medical providers by some Hispanic/Latino people.18,19

- Discrimination and distress related to immigration policies, such as the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, have led many people who live in immigrant communities to avoid interacting with public officials.20,21 As a result, many Hispanic/Latino people who are legally eligible for public health insurance coverage or health services do not enroll.20 Additionally, anti-immigrant public discourse, as well as decreased access to employment, has caused distress.22

There are also current reasons—like the ones explored below—that help explain why commercial tobacco* affects the health of Hispanic/Latino people.

The tobacco industry targets Hispanic/Latino communities with marketing and advertising.

Marketing plays a big role in whether people try or use commercial tobacco products. Commercial tobacco ads make smoking seem more appealing and increase the chance that someone will try smoking for the first time or start using commercial tobacco products regularly.11,23,24,25

Cigarillos and little cigars are often marketed and advertised to Hispanic and Latino people.

- Tobacco companies heavily advertise Spanish-language cigarette brand names such as “Rio” and “Dorado” to the Hispanic/Latino community, including ads in many Spanish-language publications.26

- Tobacco companies have donated to influential community groups, universities and colleges, and scholarship programs supporting Hispanic/Latino people.26 The tobacco industry has also provided significant support to Hispanic/Latino political organizations, cultural events, and the Hispanic/Latino art community.26

- Tobacco companies use price promotions such as discounts of products like cigarillos and little cigars in neighborhoods with a higher concentration of Hispanic/Latino people. In one study, little cigars and cigarillos were more likely to be sold by stores in communities with a majority of Hispanic/Latino residents (vs majority non-Hispanic White residents). In the same study, most stores surveyed in communities with a majority of Hispanic/Latino residents sold such products for less than $1.27

- A 2009 federal law prohibited cigarette and smokeless tobacco brand-sponsorship of cultural events, but other product types, like e-cigarettes and little cigars, are not covered by these restrictions. Tobacco companies are still promoting cultural events designed to bring in youth of color – like a recent campaign for little cigars that held pop-up concerts featuring hip-hop stars in convenience stores.28

To help protect Hispanic/Latino people from tobacco marketing and discourage tobacco product use, states and communities could consider increasing prices and prohibiting price discounts, prohibiting the sale of flavored tobacco products, and either allowing fewer stores in a neighborhood to sell commercial tobacco products or prohibiting tobacco product sales altogether.29

Healthcare itself can be a source of discrimination. Nearly 1 in 5 Hispanic people report they avoid medical care due to concern of being discriminated against or treated poorly.37

When people have severe or long-lasting stress, their bodies respond by raising stress hormones and keeping them raised. When this goes on for a long time, they may develop health problems like high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.38,39 Smoking cigarettes also leads to disease and disability and harms nearly every organ in the body.11

- Kaplan RC, Bangdiwala SI, Barnhart JM, et al. Smoking among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults: the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(5):496‐506 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022; 71:397–405

- Pérez-Stable EJ, Ramirez A, Villarea R, Talavera GA, Trapido E, et al. Cigarette smoking behavior among US Latino men and women from different countries of origin. American Journal of Public Health. 2001; 91(9):1424-1430 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Substance Abuse & Mental Health Data Archive. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2-Year RDAS (2018 to 2019) online analysis tool [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, et al. Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors Among Middle and High School Students — National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71(No. SS-5):1–29. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7105a1

- U.S. Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States and States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Release Date: June 2020 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- U.S. Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Release Date: December 2019 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Leading Causes of Death, Prevalence of Diseases and Risk Factors, and Use of Health Services Among Hispanics in the United States—2009–2013. MMWR Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 2015;64(17):469–78 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2010. [PDF - 5.1 MB] National Vital Statistics Reports, 2013; 62(6) [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: Final data for 2013. [PDF - 7.3 MB] National Vital Statistics Reports, 2016;64(2) [accessed 2022 Mar 1

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- 2018 National Health Interview Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Feagin, J.R., & Cobas, J.A. (2014). Latinos Facing Racism: Discrimination, Resistance, and Endurance (1st ed.). Routledge [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Carrigan WD, Clive W. The lynching of persons of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928. Journal of Social History. 2003: 411-438 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Langton L, Masucci M. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics 2017. Hate Crime Victimization, 2004-2015 [PDF - 588 KB] [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Ochoa EC. From Tortillas to Low-carb Wraps: Capitalism and Mexican Food in Los Angeles since the 1920s. Diálogo. 2015;18(1): 33-46 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Hernández-Valero MA, Bustamante-Montes LP, Hernández M, Halley-Castillo E, Wilkinson AV, Bondy ML, et al. Higher risk for obesity among Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant children and adolescents than among peers in Mexico. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012; 14(4): 517–522 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Armstrong, K, Ravenell KL, McMurphy S, Putt, M. Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007; 97(7): 1283–1289 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Novak NL, Lira N, O’Connor KE, Harlow SD, Kardia SL, Stern AM. Disproportionate sterilization of Latinos Under California’s Eugenic Sterilization Pprogram, 1920–1945. American Journal of Public Health. 2018; 108(5): 611-613 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Perreira, Krista M., and Juan M. Pedroza. Policies of exclusion: implications for the health of immigrants and their children. [PDF - 349 KB] Annual review of public health 40 (2019): 147-166 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Pedraza FI, Nichols VC, LeBrón AMW. Cautious citizenship: the deterring effect of immigration issue salience on health care use and bureaucratic interactions among Latino US citizens. J. Health Polit. Policy Law. 2017, 42(5):925–60 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hirsch JS. State-level Immigration and Immigrant-Focused Policies as Drivers of Latino Health Disparities in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2018; 1982(199): 29-38 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Carson NJ, Rodriguez D, Audrain-McGovern J. Investigation of mechanisms linking media exposure to smoking in high school students. Prev Med 2005;41(2): 511-20 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: A review. Pediatrics 2005;116(6): 1516-28 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. NIH Pub. No. 07-6242, June 2008.

- Robinson RG, Barry M, Bloch M, Glantz S, Jordan J, Murray KB, Popper E, et al. Report of the Tobacco Policy Research Group on Marketing and Promotions Targeted at African Americans, Latinos, and Women. Tobacco Control. 1992; 1 (Suppl 1): S24-S30 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Smiley SL, Kintz N, Rodriguez YL, Barahona R, Sussman S, Cruz TB, Chou CP, Pentz MA, et al. Disparities in Retail Marketing for Little Cigars and Cigarillos in Los Angeles, California. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2019; 9:100149[accessed 2021 Dec 8].

- Ganz O, Rose SW, Cantrell J. Swisher Sweets ‘Artist Project’: Using Musical Events to Promote Cigars. Tobacco Control. 2018; 27:e93-e95 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, Hoek J. A Systematic Review on the Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Promotion on Smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015:17(1): 2-17[accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Slopen N, Kontos EZ, Ryff CD, Ayanian JZ, Albert MA, Williams DR. Psychosocial stress and cigarette smoking persistence, cessation, and relapse over 9-10 years: a prospective study of middle-aged adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(10):1849-1863 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Slopen N, Dutra LM, Williams DR, et al. Psychosocial stressors and cigarette smoking among African American adults in midlife. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(10):1161-1169 [accessed 2022 Apr 28].

- Purnell JQ, Peppone LJ, Alcaraz K, et al. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress, and current smoking status: results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Reactions to Race module, 2004-2008. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):844-851 [accessed 2022 Apr 28].

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey, 2009 to 2020. Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2019, ERR-275, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Economic Research Service. 2020 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Slavich GM. Life Stress and Health: A Review of Conceptual Issues and Recent Findings. Teaching of Psychology. 2016; 43(4): 346-355[accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Discrimination in America: Experiences and Views on Effects of Discrimination Across Major Population Groups in the United States. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and National Public Radio. 2017 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Discrimination in America: Experiences and Views of Latinos [PDF-1.0 MB]; a 2017 poll developed by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and National Public Radio (NPR). [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35(1): 2-16 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Guyll M, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT. Discrimination and unfair treatment: relationship to cardiovascular reactivity among African American and European American women. Health Psychology. 2001;20(5): 315 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2018 [PDF - 148 KB] [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Wilson KM, Klein JD, Blumkin AK, Gottlieb M, Winickoff JP. Tobacco-smoke exposure in children who live in multiunit housing. Pediatrics. 2011; 127 (1): 85-92 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Merianos AL, Jandarov RA, Choi K, Mahabee-Gittens EM. Tobacco smoke exposure disparities persist in U.S. children: NHANES 1999-2014. Prev Med. 2019;123:138-142 [accessed 2022 Apr 28].

- Cancer Trends Progress Report. National Cancer Institute, NIH, DHHS, Bethesda, MD, July 2021 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Brody DJ, Lu Z, Tsai J. Secondhand Smoke Exposure Among Nonsmoking Youth: United States, 2013-2016. [PDF - 500 KB] NCHS Data Brief, 2019 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Pizacani BA, Maher JE, Rohde K, Drach L, and Stark MJ. Implementation of a smoke-free policy in subsidized multiunit housing: effects on smoking cessation and secondhand smoke exposure. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14(9): 1027-1034 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Shopland DR, Anderson CM, Burns DM, Gerlach KK. Disparities in smoke-free workplace policies among food service workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2004;46(4): 347-356 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Holmes LM, Ling PM. Workplace secondhand smoke exposure: a lingering hazard for young adults in California. Tobacco Control.2017; 26(e1): e79–e84 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Hafez AY, Gonzalez M, Kulik MC, Vijayaraghavan M, Glantz S. Uneven access to smoke-free laws and policies and its effect on health equity in the United States: 2000–2019. American Journal of Public Health. 2019; 109(11): 1568-1575 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Americans Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. Bridging the Gap: Status of Smokefree Air in the United States [PDF - 149 KB] [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2000-2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2017;65(52):1457-64 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2020 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Carter-Pokras OD, Feldman RH, Kanamori M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation among Latino adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(5):423– 431 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Babb S, Malarcher A, Asman K, Johns M, Caraballo R, VanFrank B, et al. Disparities in Cessation Behaviors Between Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Adult Cigarette Smokers in the United States, 2000–2015. Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17:190279 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Zhang L, Babb S, Johns M, Mann N, Thompson J, Shaikh A, et al. Impact of US antismoking TV ads on Spanish-language quitline calls. American Journal of Preventive Medicine.2018; 55(4): 480-487 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- DiGiulio A, Jump Z, Babb S, et al. State Medicaid Coverage for Tobacco Cessation Treatments and Barriers to Accessing Treatments — United States, 2008–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:155–160 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Lebrun-Harris LA, Fiore MC, Tomoyasu N, and Ngo-Metzger Q. Cigarette Smoking, Desire to Quit, and Tobacco-Related Counseling Among Patients at Adult Health Centers. American Journal of Public Health 2015; 105 (1): 180-188 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Flocke SA, Hoffman R, Eberth JM, Park H, Birkby G, Trapl E, et al. The Prevalence of Tobacco Use at Federally Qualified Health Centers in the United States, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2017; 14:160510 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Castro Y. Determinants of Smoking and Cessation Among Latinos: Challenges and Implications for Research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2016;10(7): 390-404 [accessed 2022 Mar 1].

- Borrelli B, McQuaid EL, Novak SP, Hammond SK, Becker B. Motivating Latino caregivers of children with asthma to quit smoking: a randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(1):34‐43 [accessed 2022 Mar1].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices User Guide: Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control. [5.04 MB] Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2015 [accessed 2022 Apr 28].F