Venereal Disease Program

An Agency to Serve the Public

Next, the exhibit explores how CDC became an agency to serve the public through the “Great Society” program started by President Lyndon B. Johnson. For this program, Congress passed legislation that fought against poverty; protected civil rights; and aimed to improve education, health, and mass transit.

This legislation reflected an expanding belief in social progress – essentially building a greater society in the U.S. In this social context, CDC expanded its public health programs in the 1960s and early 1970s. While surveillance of infectious diseases was still central to CDC’s work, disease prevention was also emphasized. By 1970, the agency’s work included chronic disease prevention, environmental health, injury control, and workplace safety.

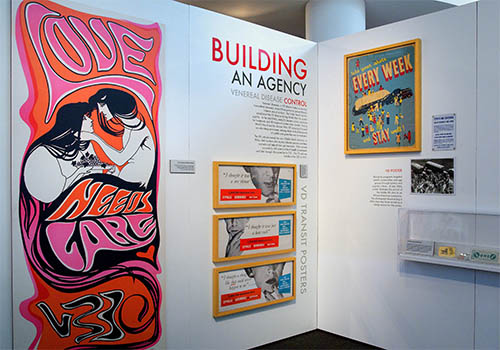

Building an Agency: Venereal Disease Control

In 1957, the Public Health Service, CDC’s parent agency, transferred its Venereal Disease Division to CDC. Venereal disease, or VD, is the older term for what now is referred to as sexually transmitted diseases, or STDs.

While CDC currently studies many STDs, during the 1950s and 1960s the primary focus was on syphilis and gonorrhea. Each of the two diseases is caused by a different bacterium and is spread through sexual contact.

Public Health Advisors

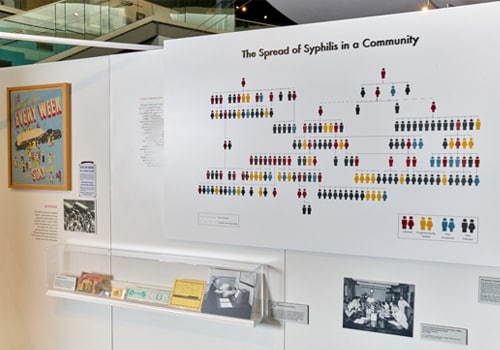

Tasked with stopping the spread of STDs in the U.S., CDC created a new role: the Public Health Advisor, or PHA. PHAs were a corps of college graduates with liberal arts backgrounds who were assigned to state health departments to help organize programs for disease prevention and control. Their jobs were to work in communities to determine which people had venereal diseases, and to encourage those who tested positive for VDs to seek treatment. Once PHAs identified a case of VD, they would ask that person if they would be willing to share information about their sexual and close social contacts. The PHAs would then speak to the contacts to see if they would be willing to get tested for VDs as well. This method of using a confirmed case of a disease’s contacts to find other cases of a disease was called “contact epidemiology.” To this day, CDC frequently uses contact epidemiology to track the spread of diseases, but it is now sometimes referred to as contact tracing.

Shown here is a 1950s contact tracing chart that demonstrates how syphilis spreads in a community. The chart includes people without syphilis, those with unknown disease status, those receiving preventative treatment, and those who do have syphilis. The chart also shows if individuals have a sexual relationship or a close social relationship. Contact tracing charts like these were one of the epidemiological tools the PHAs used to track the health of people in their assigned communities and remain a useful tool for CDC.

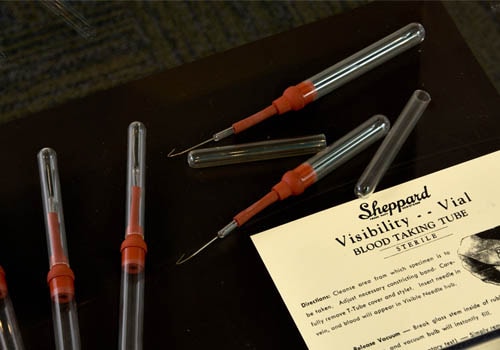

Sheppard Tubes

Pictured here are Sheppard Tubes, which were used by PHAs to collect blood samples to then test for venereal diseases. Sheppard tubes are glass tubes approximately one-half inch in diameter and four inches in length. The tubes were vacuum packed, helping draw blood into the tube from the patient’s vein once the needle was inserted. The tubes allowed for quick blood sample collection by PHAs.