Diagnosis and Treatment of Malaria in the Malaria-Endemic World

Note: This page describes malaria diagnosis and treatment in malaria-endemic areas. For information about malaria diagnosis and treatment in the United States, click here.

Malaria must be diagnosed and treated promptly with a recommended antimalarial drug to keep the illness from progressing and to help prevent further spread of infection in the community.

In the malaria-endemic world, diagnosis of malaria can be difficult for several reasons:

- Malaria’s clinical symptoms are shared with other diseases and conditions, and many malaria-endemic countries lack resources, such as microscopes and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), to make a definitive diagnosis.

- Health personnel in these areas are often undertrained, underequipped and underpaid.

- Health personnel in the malaria-endemic world often face excessive patient loads, and must divide their attention between malaria and other equally severe infectious diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhea, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS.

Malaria may be “uncomplicated” or “severe.”

- Uncomplicated malaria: Symptoms may include fever, chills, sweats, headaches, muscle pains, nausea and vomiting.

- Severe malaria: Symptoms may include confusion, coma, focal neurologic signs, severe anemia, and respiratory difficulties. A patient with symptoms of severe malaria should be assessed quickly and treated immediately. Severe malaria is most often caused by the most dangerous parasite, Plasmodium falciparum.

Diagnosis of Malaria

When a patient with fever is brought to a health facility in the malaria-endemic world, a health worker may suspect that the patient has malaria based on the patient’s symptoms, although these symptoms are not specific to malaria. For many years, national malaria control programs recommended treating children under 5 years with fever for malaria, based on symptoms alone, because most health facilities did not have working microscopes, a trained microscopist, and necessary equipment (e.g., slides, stains) to perform a laboratory test. Malaria was extremely common and potentially fatal, and providing treatment based on clinical diagnosis alone could save the child’s life. However, if the child had an illness other than malaria, it would go untreated.

As malaria interventions have been scaled up in sub-Saharan Africa in the last decade, rapid diagnostic tests for malaria have become available in health facilities, microscopes have been provided, and microscopists have been trained.

In 2010, the World Health Organization recommended that all suspected cases of malaria be confirmed with a diagnostic test prior to treatment. The Roll Back Malaria Partnership has set new targets of universal access to malaria diagnostic testing in public and private sectors as well as at the community level. In many countries, community health workers (CHWs) have been trained on integrated community case management of common childhood illnesses, including malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea. Many CHWs are being trained to use rapid diagnostic tests for febrile children and to treat them with recommended antimalarials if they are positive.

Diagnosis Based on Laboratory Methods

Microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests can be used to make a definitive diagnosis of malaria.

Microscopy

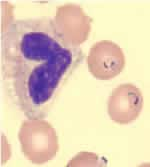

Malaria parasites can be identified by examining a drop of the patient’s blood under the microscope. This drop is spread out as a “blood smear” on a microscope slide. Before the slide is examined, the blood specimen is stained (most often with the Giemsa stain) to give the parasites a distinctive appearance. This technique is the gold standard for laboratory confirmation of malaria. However, it depends on the quality of the reagents, the quality of the microscope, and the experience of the laboratory technician.

More on: Malaria Microscopy

Rapid Diagnostic Tests

Over the last fifteen years, test kits have become available that can detect antigens derived from malaria parasites in a person’s blood. These immunologic (“immunochromatographic”) tests are referred to as RDTs and provide results quickly—depending on the test, in about 20 minutes.

RDTs offer a useful alternative to microscopy in situations where reliable microscopic diagnosis is not available. Malaria RDTs are currently used in many clinical settings and programs in countries where malaria is transmitted. CDC and others are conducting operational research to help optimize their use.

Blood smear stained with Giemsa, showing a white blood cell (on left side) and several red blood cells, two of which are infected with Plasmodium falciparum (on right side).

The WHO Malaria RDT Product Testing Programme, coordinated by WHO/TDR and the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) and executed in collaboration with CDC, provides comparative data on the performance of various RDTs available in the market to assist in procurement. Since 2008, more than 290 products have been evaluated over seven rounds of the WHO Malaria RDT Product Testing Programme.

More on: Rapid Diagnostic Tests

Treatment

The World Health Organization recommends that patients in malaria-endemic areas be treated within 24 hours after their first symptoms appear.

Treatment of a patient with malaria depends on the country’s national guidelines, which typically take the following into consideration:

- Type (species) of the infecting parasite

- Clinical status of the patient

- Any accompanying illness(es) or condition(s)

- Pregnancy

- Drug allergies, or other medications taken by the patient

- Where the infection was acquired and the presence of antimalarial drug resistance there.

Uncomplicated Malaria

Patients who have uncomplicated malaria can be treated on an outpatient basis; however, patients with severe malaria should be hospitalized.

Most drugs recommended for treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases in the malaria-endemic world are active against the parasite forms in the blood (the form that causes disease). Listed below are some of the drugs approved by the World Health Organization and those most commonly recommended by national malaria control programs in the malaria-endemic world:

- Artemesinin-based combination treatments, (e.g, artemether-lumefantrine, artesunate-amodiaquine)

- Chloroquine*

- Doxycycline

- Mefloquine*

- Quinine

*Two of these drugs, chloroquine and mefloquine, are no longer effective in some or many parts of the world.

More on: Treatment in the United States

Another drug, primaquine, is used as an adjunct for certain species of malaria (e.g., P. falciparum, P. vivax, and P. ovale). It is active against the dormant parasite liver forms (hypnozoites) and can prevent relapses of P. vivax and P. ovale. Primaquine should not be taken by pregnant women or by people who are deficient in G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase). Patients should not take primaquine until a screening test has excluded G6PD deficiency or unless the risk of deficiency in the surrounding population is known to be low, because primaquine given to people with G6PD deficiency can cause hemolytic anemia. In some countries, primaquine is also used in a single dose to prevent secondary transmission of P. falciparum.

Counterfeit and substandard drugs are sold in some areas and should be avoided.

Severe Malaria

Severe malaria occurs when an infection is complicated by serious organ failure or abnormalities in the patient’s blood or metabolism.

More on: Malaria Symptoms – Severe Malaria

Patients who have severe P. falciparum malaria or who cannot take oral medications should be given treatment by continuous parenteral infusion in a hospital. The World Health OrganizationExternal

Intravenous treatment must be followed up with a complete course of oral antimalarial drugs, usually an artemisinin-based combination therapy or, when the preceding is not available, quinine plus doxycycline or quinine plus clindamycin.

In severe malaria (caused by Plasmodium falciparum) the drug quinine must be administered by intravenous perfusion. Emergency room of the St Marc Hospital in Kingasani, outskirts of Kinshasa, DR Congo.