Viral Hepatitis Surveillance – United States, 2010

Introduction

As part of CDC’s National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS), viral hepatitis case-reports are received electronically from state health departments via CDC’s National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance (NETSS), a computerized public health surveillance system that provides CDC with data regarding cases of nationally notifiable diseases on a weekly basis. Although surveillance infrastructure is in place for reporting of acute infection, reports of chronic hepatitis B and C, which account for the greatest burden of disease, are not submitted by most states. As noted in the 2010 report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (1), surveillance capacity to monitor both acute and chronic viral hepatitis is limited at the state and local levels, resulting in incomplete and variable data.

Background

Viral hepatitis is caused by infection with any of at least five distinct viruses: hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV), and hepatitis E virus (HEV). Most viral hepatitis infections in the United States are attributable to HAV, HBV, and HCV. All three of these unrelated viruses can produce an acute illness characterized by nausea, malaise, abdominal pain, and jaundice, although many of these acute infections are asymptomatic or cause only mild disease. Many persons infected with HBV or HCV are unaware they are infected. Both viruses can produce chronic infections that often remain clinically silent for decades while increasing risk for liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatitis A

Transmitted through the fecal-oral route, HAV is acquired primarily through close personal contact and foodborne outbreaks. Since 1995, effective vaccines to prevent hepatitis A virus infection have been available in the United States, increasing the feasibility of eliminating indigenous transmission. In 1996, CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of hepatitis A vaccine to persons at increased risk for the disease, including international travelers, men who have sex with men (MSM), non-injection and injection-drug users (IDUs), and children living in communities with high rates of disease (2,3). In 1999, ACIP also recommended routine vaccination for children living in 11 Western states with average hepatitis A rates of >20 cases per 100,000 population and recommended that vaccination be considered for children in an additional six states with rates of 10–20 cases per 100,000 population (4). ACIP expanded these recommendations in 2006 to include routine vaccination of children in all 50 states (5).

Hepatitis B

HBV is transmitted by percutaneous or mucosal exposure to the blood or body fluids of an infected person, most often through injection-drug use, from sexual contact with an infected person, or from an infected mother to her newborn during childbirth. Transmission of HBV also can occur among persons who have prolonged but nonsexual interpersonal contact with someone who is HBV-infected (e.g., household contacts).

The risk for chronic HBV infection decreases with increasing age at infection. Among infants who acquire HBV infection from their mothers at birth, as many as 90% become chronically infected, whereas 30%–50% of children infected at age 1–5 years become chronically infected. This percentage is smaller among adults, in whom approximately 5% of all acute HBV infections progress to chronic infection ( 6). Effective hepatitis B vaccines have been available in the United States since 1981. Ten years later, a comprehensive strategy was recommended for the elimination of HBV transmission in the United States ( 7, 8). This strategy encompassed the following four components:

- universal vaccination of infants beginning at birth;

- prevention of perinatal HBV infection through routine screening of all pregnant women for HBV infection and the provision of immunoprophylaxis to infants born either to infected women or to women of unknown infection status;

- routine vaccination of previously unvaccinated children and adolescents; and

- vaccination of adults at increased risk for infection (including health-care workers, dialysis patients, household contacts and sex partners of persons with chronic HBV infection, recipients of certain blood products, persons with a recent history of having multiple sex partners concurrently, those with a sexually transmitted disease, MSM, and IDUs).

In addition to hepatitis B vaccination, efforts have been made to improve care and treatment for persons who are living with hepatitis B. In the United States, 804,000-1.4 million persons are estimated to be infected with the virus (9), most of whom are unaware of their infection status. To improve health outcomes for these persons, in 2008, CDC issued recommendations to guide hepatitis B testing and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection (9). These guidelines stress the need for testing persons at high risk for infection, conducting contact management, educating patients, and administering FDA-approved therapies for treating hepatitis B. Since publication of the 2008 guidelines, treatment options for HBV infection have expanded. Several drugs are now administered orally (a major advancement in how treatments are administered for this infection), leading to viral suppression in 90% of patients taking one of these new oral medications.

Hepatitis C

HCV is transmitted primarily through percutaneous exposure, which can result from injection-drug use, needle-stick injuries, receipt of blood or blood products before the availability of a standard screening test (1992) and inadequate infection control in health-care settings (10). Much less often, HCV transmission occurs among HIV-positive MSM as a result of sexual contact with an HIV-infected partner (11,12) and among infants born to HCV-infected mothers. With an estimated 3.2 million chronically infected persons nationwide, HCV infection is the most common blood-borne infection in the United States (13).

No laboratory distinction can be made between acute and chronic (past or present) HCV infection. Diagnosis of chronic infection is made on the basis of anti-HCV positive results upon repeat testing. Approximately 75%-85% of newly infected persons develop chronic infection (14).

Because of the high burden of chronic HCV infection in the United States and because no vaccine is available for preventing infection, national recommendations (15) emphasize other primary prevention activities, including screening and testing blood donors, inactivating HCV in plasma-derived products, testing persons at risk for HCV infection and providing them with risk-reduction counseling, and consistently implementing and practicing infection control in health-care settings. Since publication of these recommendations in 1998, progress has been made in HCV testing; FDA recently approved point-of-care tests for HCV infection, which can facilitate testing, notification of results and post-test counseling, and referral to care at the time of the testing visit (16).

Linkage to care and treatment is critical to improving health outcomes for persons found to be infected with HCV. Such linkage is particularly important in light of the major advancements that have been made in treatment of hepatitis C. Treatment success rates are now being improved with the addition of polymerase and protease inhibitors to standard pegylated interferon/ribavirin combination therapy ( 17).

References

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2010.

- CDC. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, eds. 11th ed. Washington DC: Public Health Foundation, 2009.

- CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR 1996; 45(No. RR-15).

- CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization. MMWR 1999; 48(No. RR-12).

- CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2006;55(No. RR-7).

- CDC. Overview of Viral Hepatitis for Health Care Professionals.

- CDC. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR 2005; 54(No. RR–16).

- CDC. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Part 2: immunization of adults. MMWR 2006; 55(No. RR–16).

- CDC. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR 2008;57(No. RR-08).

- Thompson ND, Perz JF, Moorman AC, Holmberg SD. Nonhospital health care-associated hepatitis B and C virus transmission: United States, 1998- 2008. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:33-9.

- Tohme RA, Holmberg SD. Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C transmission? Hepatol 2010; 52:1497–1505

- CDC. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among HIV-infected men who have sex with men—New York City, 2005-2010. MMWR 2011;60:945-950.

- Armstrong GL, Wasley AM, Simard EP, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:705–14.

- CDC. National hepatitis C prevention strategy: a comprehensive strategy for the prevention and control of hepatitis C virus infection and its consequences. 2001.

- CDC. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR 1998;47(No. RR–19).

- Lee SR, Yearwood GD, Guillon GB, et al. Evaluation of a rapid, point-of-care test device for the diagnosis of hepatitis C infection. J Clin Virol 2010;48(1):15-7.

- Vachon ML, Dieterich DT. The era of direct-acting antivirals has begun: the beginning of the end for HCV? Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:399-409.

Technical Notes

Investigations

Recent investigations of viral hepatitis outbreaks in the United States demonstrate the continued risk posed by lapses in infection-control practices, particularly in health-care settings (1). Distinguishing cases of health-care-acquired viral hepatitis from those transmitted outside the health-care setting often depends on the quality of case reporting and therefore varies by state and locality. Investigation of suspected cases of health-care-associated viral hepatitis is multi-faceted, and labor intensive involving surveillance, epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory components. State and local health departments generally consult CDC’s DVH and the Division of Health care Quality Promotion (DHQP) for technical assistance and support regarding the proper approach to investigating a possible health care-associated transmission event.

As of 2010, CDC increased the number of tools available to investigate potential health care-associated transmission of viral hepatitis (https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Outbreaks/index.htm). Outbreaks reported and investigated (2-6) through 2011 are now available as Table 1 at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Outbreaks/HealthcareHepOutbreakTable.htm.

Data regarding viral hepatitis outbreaks obtained through current surveillance mechanisms are subject to limitations. Because not all outbreaks are identified or investigated at the state and local level or reported to CDC, the number of reported outbreaks for 2010 likely is an underestimate of the actual number of viral hepatitis outbreaks that occurred in health-care or other congregant living facilities.

References

- Thompson ND, Perz JF, Moorman AC, Holmberg SD. Nonhospital health care-associated hepatitis B and C virus transmission: United States, 1998-2008. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:33-39.

- Bancroft E, Hathaway S. Hepatitis B Outbreak in an Assisted Living Facility. Acute Communicable Diseases Program, Special Studies Report 2010, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Available at: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/acd/HepInfo.htm

- CDC. Deaths from acute hepatitis B virus infection associated with assisted blood glucose monitoring in an assisted-living facility — North Carolina, August–October 2010. MMWR 2011; 60:182.

- Tohme R, Awosika-Olumoc D, Nielsenb C, Khuwajac S, Scott J, Xing J, Drobeniuc J, Hu D, Turner C, Wafee T, Sharapov U, Spradling P. Evaluation of hepatitis B vaccine immunogenicity among older adults during an outbreak response in assisted living facilities. Vaccine 2011; 29: 9316-9320.

- Bancroft E, Hathaway S, Itano A. Pain Clinic Hepatitis Investigation Report. Acute Communicable Diseases Program, Special Studies Report 2010, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Available at: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/wwwfiles/ph/dcp/acd/SpecialStudiesReport2010.pdf [PDF – 94 pages]

- Hellinger WC, Bacalis LP, Kay RS, Thompson ND, Xia GL, Lin Y, Khudyakov YE, Perz JF. Health care–associated hepatitis C virus infections attributed to narcotic diversion. Manuscript submitted.

National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System

Background

Each week, state and territorial health departments report cases of acute, symptomatic viral hepatitis to CDC’s NNDSS. Since 1990, states have been electronically submitting individual case reports (absent of personal identifiers) to CDC via NETSS, a computerized public health surveillance information system. States’ participation in reporting nationally notifiable diseases, including viral hepatitis, is voluntary.

National surveillance for viral hepatitis (including acute hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C; chronic hepatitis B; and chronic [past or present] hepatitis C) is based on case definitions developed and approved by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and CDC. In 2010, health departments were asked to report cases of acute and chronic viral hepatitis meeting CSTE-defined clinical and laboratory criteria (available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/#h).

Case Definitions

Acute Viral Hepatitis

Clinical Criteria

Acute hepatitis is defined as acute illness with 1) discrete onset of symptoms (e.g., nausea, anorexia, fever, malaise, and abdominal pain) and 2) jaundice or elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. For acute hepatitis C, elevated ALT levels are defined as >400 IU/L.

Laboratory Criteria

Because all types of acute viral hepatitis have the same clinical characteristics, identifying the specific viral cause of illness requires laboratory testing. The following laboratory criteria are used to determine the cause of each suspected case of acute viral hepatitis:

Acute hepatitis A

- Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to hepatitis A virus (anti-HAV) positive.

Acute hepatitis B

- IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) positive or hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive

AND

- IgM anti-HAV negative (if performed).

Acute hepatitis C

- IgM anti-HAV negative and IgM anti-HBc negative

AND

- One of the following:

- Antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) positive, with a signal-to-cut-off ratio predictive of a true positive for the particular assay as defined by CDC (signal to cut-off ratios available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/LabTesting.htm#section1)

OR

- Hepatitis C virus recombinant immunoblot assay (HCV RIBA) positive

OR

- Nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA positive.

Chronic Hepatitis B

Clinical Criteria

No symptoms are required. Persons with chronic HBV infection may have no evidence of liver disease or may have a spectrum of disease ranging from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Laboratory criteria for diagnosis

- IgM anti-HBc negative

AND

- a positive result on one of the following tests: HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) or HBV DNA

OR

- Two positive tests for HBsAg, HBV DNA, or HBeAg when tests are performed at least 6 months apart (any combination of these tests performed 6 months apart is acceptable).

Chronic Hepatitis C, past or present

Because current laboratory diagnostic tests do not distinguish current active infections (present) from resolved infections (past), the term “past or present” is used to describe HCV positive results after repeat testing.

Clinical description

No symptoms are required. Most HCV-infected persons are asymptomatic. However, many have mild-to-severe chronic liver disease, which can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Laboratory Criteria

- Anti-HCV positive (repeat reactive) by EIA, verified by an additional, more specific assay (e.g., RIBA for anti-HCV or nucleic acid testing for HCV RNA)

OR

- HCV RIBA positive

OR

- Nucleic acid test for HCV RNA positive

OR

- Report of HCV genotype

OR

- Antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) positive, with a signal-to-cut-off ratio predictive of a true positive for the particular assay as defined by CDC (signal to cut-off ratios available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/LabTesting.htm#section1)

Case Classification

For analysis at the national level, cases of viral hepatitis are considered “confirmed” if they meet both the clinical case definition and laboratory criteria for diagnosis; however, these criteria are determined at the state or local level and are not validated by CDC. For hepatitis A, cases also are considered confirmed if they meet the clinical case definition and involve a person who is epidemiologically linked to someone with laboratory-confirmed hepatitis A (e.g., through household or sexual contact with an infected person during the 15–50 days before symptom onset). In this report, Hispanics could be of any race and persons categorized by race were not Hispanic or Latino.

Incidence Calculations

For this report, crude national rates per 100,000 population were calculated using 2010 Census estimates of the U.S. resident population. State-specific rates were calculated using 2010 Census population estimates for each state.

Limitations

NNDSS is a passive surveillance system and is subject to several limitations regarding acute and chronic viral hepatitis reporting. First, NNDSS was designed for reporting acute infectious disease for which a single laboratory test (e.g., culture positivity) confirms a diagnosis. This limitation is especially problematic for cases of HBV and HCV infection; for example, an average of four documents or reports must be reviewed to identify each new case of acute hepatitis C virus infection (1). Further, follow-up of patients is difficult. With the exception of selected, specially funded sites, states and localities do not receive federal funding to support viral hepatitis surveillance.

Although rate calculations using NNDSS data substantially underestimate the incidence of acute viral hepatitis in the United States ( 2-4), methods used to determine incidence rates have remained consistent since 1990 (CDC, unpublished data, 2007). Therefore, data from NNDSS are useful to assess trends in viral hepatitis over time. National trends in acute disease published in this report are consistent with those demonstrated in CDC’s Sentinel Counties Study of Acute Viral Hepatitis, in which the accuracy and completeness of reporting were assessed and known to be high ( 4). As noted, accuracy is less certain for chronic hepatitis B and past or present hepatitis C cases, as many states lack resources to conduct surveillance for chronic viral hepatitis, follow-up potential cases, and evaluate the data.

References

- Klevens RM, Miller J, Vonderwahl C, et al. Population-based surveillance for hepatitis C virus, United States, 2006–2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:1499–1502.

- Doyle TJ, Glynn MK, Groseclose SL. Completeness of notifiable infectious disease reporting in the United States: an analytical literature review. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:866–74.

- Armstrong GL, Bell BP. Hepatitis A virus infections in the United States: model-based estimates and implications for childhood immunization. Pediatrics 2002;109:839–45.

- Alter MJ, Mares A, Hadler SC, Maynard JE. The effect of underreporting on the apparent incidence and epidemiology of acute viral hepatitis. Am J Epidemiol 1987;125:133–9.

Estimation Procedures

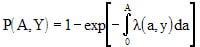

CDC’s DVH employs catalytic and general linear models to estimate acute viral hepatitis infection rates (1). The accuracy of these estimates is contingent on the quality of the data and the primary assumption that hepatitis prevalence can be modeled as a function of hepatitis incidence. The general catalytic model is expressed as:

where P(A,Y) denotes disease prevalence for a specific age (A), and survey year (Y); λ(a,y) denotes age-specific disease incidence in a susceptible population (2).

Estimates of acute hepatitis infection rates are adjusted for the possible effects of underreporting and the exclusion of asymptomatic infections from the number of reported acute, symptomatic infections. For at least the past 5 years, adjustment multipliers have remained unchanged, although DVH is currently collaborating with state viral hepatitis programs to collect the necessary data required to update both adjustment multipliers.

Consistent with past surveillance reports, the following adjustments were applied to the 2010 data:

- for each newly reported HAV symptomatic infection, approximately 10.4 new HAV infections (of which 4.3 and 6.1 cases were symptomatic and asymptomatic, respectively) are estimated to occur in the general population;

- for each newly reported HBV symptomatic infection, approximately 10.5 new HBV infections (of which 2.8 and 7.7 cases were symptomatic and asymptomatic, respectively) are estimated to occur in the general population; and

- for each new reported HCV symptomatic infection, approximately 20.0 new HCV infections (of which 3.3 and 16.7 cases were symptomatic and asymptomatic, respectively) are estimated to occur in the general population.

References

- Armstrong GL, Bell BP. Hepatitis A virus infections in the United States: model-based estimates and implications for childhood immunization. Pediatrics 2002;109:839–45.

- Muench H. Catalytic models in epidemiology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 1959.

Enhanced Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Sites

Background

CDC funds select sites for more active viral hepatitis surveillance through the Emerging Infections Program (EIP), a network involving CDC, state health departments, academic institutions, and local health departments. Since 2004, participating EIP sites have conducted routine surveillance for chronic HBV and chronic (past or present) HCV infections. All chronic cases of viral hepatitis obtained through these sites are de-duplicated; additionally, for a percentage of cases, follow-up is conducted to obtain clinical and laboratory data and information regarding risk behaviors/exposures. Each month, a dataset of cumulative cases from each site is sent to CDC via a secure electronic file transfer protocol (FTP).

Methods

Data Collection

).

Methods

Data Collection

In 2010, CDC funded five states (Colorado, Connecticut, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York and Oregon), and two cities (New York City and San Francisco) to conduct viral hepatitis surveillance, representing a combined population of approximately 40 million persons. In each of these jurisdictions, clinical laboratories are mandated to submit reports from persons with positive HBV and HCV test results. Participating health departments routinely review each report to assess whether the current case definition was met as established by CSTE and CDC. To determine whether a report reflects a new case, each site matches reports to existing cases in the surveillance registry using personal identifying information. Any new cases are added to an electronic registry, whereas new reports on existing cases are used to update previous reports. Most health departments collect basic demographic information (e.g., age, sex, and race/ethnicity) from the laboratory reports. Efforts vary by site regarding the level of investigation undertaken to collect supplemental information (e.g., risk factor data) from patients or their providers.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted on all serologically confirmed cases of chronic hepatitis B and chronic (past or present) hepatitis C infection reported by EIP sites during 2010 and submitted to CDC by November 30, 2011. Rates were calculated using appropriate jurisdiction-specific (state, county, or city) 2010 population estimates obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Limitations

The numbers presented here reflect chronic cases newly reported to participating sites during 2010; persons who are infected may be asymptomatic but not tested or diagnosed and thus not reported to surveillance. New reports may not represent new diagnoses. Participating sites may not be representative of the U.S. population, and finally, because sites conduct follow-up as feasible, data regarding race/ethnicity, place of birth, and risk are missing for some case reports.

Mortality/Death Certificates

Background

Death certificates are completed for all deaths registered in the United States. Information from death certificates is provided by funeral directors, attending physicians, medical examiners, and coroners, and certificates are filed in vital statistics offices within each state and the District of Columbia. Through a program called the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) (1), information from death certificates is compiled by CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to produce national, multiple-cause-of-death (MCOD) data (2); causes of death are coded in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) (3). MCOD data are used to determine the national burden of mortality associated with viral hepatitis infections and to describe the demographic characteristics of decedents (4).

Methods

We analyzed national multiple-cause mortality data collected during 2004–2008 (the most recent years available) obtained from NCHS. The following case definitions were used to identify a death associated with hepatitis A, B, and C.

Any death record with a report of

- hepatitis A (ICD-10: B15),

- hepatitis B (ICD-10: B16, B17.0, B18.0, and B18.1), or

- hepatitis C (ICD-10: B17.1 and B18.2) listed as the underlying or one of the multiple (e.g., contributing) causes of death in the record axis.

Demographic information on age, race, and sex were examined. Deaths were divided into six age categories: 0–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and >75 years. Race categories consisted of white (Hispanic and non-Hispanic), black (Hispanic and non-Hispanic), and non-black, non-white (which included all other racial and ethnic groups).

To calculate annual national mortality rates, the number of deaths was divided by the total U.S. Census population for each demographic subgroup. Rates on race, sex, and overall total were standardized to the age distribution of the standard U.S. population in 2000 ( 5). Data were analyzed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

Interpretation of Mortality Data

- Differences in recording practices of death certificate information may cause misclassification of ICD-10 codes and demographic information.

- Certain racial/ethnic populations likely are underrepresented in U.S. Census data (the denominator for calculating rates), potentially causing overestimated rates for these populations.

- Analyses do not adjust for deaths resulting from undiagnosed viral hepatitis infections.

- Death records listing more than one type of viral hepatitis infection were counted once for each type of infection. For example, a death with ICD-10 codes for both hepatitis B and C virus infections is counted once as a hepatitis B death and once as a hepatitis C death.

- The race category designated as “non-white/non-black” includes all other race groups (e.g., APIs, AI/ANs, and persons who are Hispanic). This lack of specificity limits race-specific interpretation of mortality data.

References:

- Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Report 2010;58(19):1–73.

- National Center for Health Statitistics. Mortality data. Accessed July 1 2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/deaths.htm.

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th Revision, Version for 2007. Accessed April 23 2010. Available at: http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/.

- Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156:271-8.

- Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001;20:1–10.

Highlights of Analyses

Investigations

Outbreaks reported through 2011, including 11 in 2010, are now available as Table 1 at: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Outbreaks/HealthcareHepOutbreakTable.htm

Acute Hepatitis A

Historically, acute hepatitis A rates vary cyclically, with nationwide increases every 10–15 years. The last peak was in 1995; since that time, rates of hepatitis A have steadily declined. In 2009, a total of 1,987 acute cases of hepatitis A were reported nationwide to CDC (Table 2.1). The overall incidence rate for 2009 was 0.6 cases per 100,000 population, ranging from 0.1 case per 100,000 population in Louisiana and Maine to 1.4 cases per 100,000 population in South Carolina (Table 2.2). After asymptomatic infection and underreporting were taken into account, an estimated 21,000 new infections occurred in 2009 (see Estimation Procedures).

Table 2.1. Reported cases of acute hepatitis A, nationally and by state ― United States, 2006-2010

- The number of acute hepatitis A cases reported in the United States declined by approximately 53%, from 3,579 in 2006 to 1,670 in 2010.

- The rate of acute hepatitis A declined from 1.2 cases per 100,000 population to 0.5 cases per 100,000 population during 2006–2010.

- In 2010, the rate ranged from 0.1 case per 100,000 population (Arkansas, Mississippi, and South Dakota) to 1.0 case per 100,000 population in Arizona.

Table 2.2. Clinical characteristics of reported cases of acute hepatitis A ― United States, 2010

Of the 1,670 case reports of hepatitis A received during 2010, 56.8% included information about whether the patient had jaundice, 61.1% had information regarding hospitalization caused by hepatitis A, and 56.1% included data for hepatitis A-associated death.

- In 2010, of all case reports with information regarding clinical characteristics,

- 68.1% indicated the patient had jaundice;

- 42.5% indicated the patient was hospitalized as a result of hepatitis A; and

- 1.0% indicated the patient died from hepatitis A.

Figure 2.1. Reported number of acute hepatitis A cases – United States, 2000–2010

- The number of reported cases of hepatitis A declined by approximately 88%, from 13,397 in 2000 to 1,670 in 2010.

Figure 2.2. Incidence of acute hepatitis A, by age group – United States, 2000–2010

- Rates of hepatitis A declined for all age groups.

- Rates were similar and low among persons in all age groups in 2010 (<1.0 case per 100,000 population; range: 0.31–0.81).

Figure 2.3. Incidence of acute hepatitis A, by sex — United States, 2000–2010

- From 2000-2002, rates of acute hepatitis A were higher among males than females.

- The ratio of male to female rates was 1.9 in 2001; however, from 2006 through 2010, overall rates declined more among males than among females.

- In 2010, the incidence rate among males (0.6 cases per 100,000 population) was similar to that among females (0.5 cases per 100,000 population).

Figure 2.4. – Incidence of acute hepatitis A, by race/ethnicity — United States, 2000–2010

- During 2003–2008, rates among AI/ANs were lower than or similar to those among persons in other races. The 2010 rate of hepatitis A among AI/ANs was the lowest ever recorded (0.2 cases per 100,000 population).

- Beginning in 2008, rates among API were higher than those among all other racial/ethnic populations.

Figure 2.5. Distribution of risk behaviors/exposures associated with acute hepatitis A — United States, 2010

- Of the 1,670 case reports of acute hepatitis A received by CDC during 2010, a total of 639 (38%) cases did not include a response (i.e., a “yes” or “no” response to any of the questions about risk behaviors and exposures) to enable assessment of risk behaviors or exposures.

- Of the 1,031 case reports that had a response:

- 75% (n=774) indicated no risk behaviors/exposures for hepatitis A; and

- 25% (n=257) indicated at least one risk behavior/exposure for hepatitis A during the 2–6 weeks prior to onset of illness.

Figure 2.6a. and 2.6b. – Acute hepatitis A reports, by risk behavior/exposure — United States, 2010

Patients were asked about engagement in selected risk behaviors and exposures during the incubation period, 2–6 weeks prior to onset of symptoms.

- Of the 687 case reports that contained information about contact, 7.3% (n=50) involved persons who had sexual or household contact with a person confirmed or suspected of having hepatitis A.

- Of the 932 case reports that included information about employment or attendance at a nursery, day-care center, or preschool, 3.1% (n=29) involved persons who worked at or attended a nursery, day-care center, or preschool.

- Of the 832 case reports that included information about household contact with an employee of or a child attending a nursery, day-care center, or preschool, 4.0% (n=33) indicated such contact.

- Of the 711 case reports that had information about linkage to an outbreak, 10.4% (n=74) indicated exposure that may have been linked to a common-source foodborne or waterborne outbreak.

- Of the 687 case reports that included information about additional contact (i.e., other than household or sexual contact) with someone confirmed or suspected of having hepatitis A, 1.6% (n=11) of persons reported such contact.

- Of the 611 case reports that had information about travel, 14.1% (n= 86) involved persons who had traveled outside the United States or Canada.

- Of the 597 case reports that included information about injection-drug use, 2.0% (n=12) indicated use of these drugs.

- Of the 61 case reports from males that included information about sexual preference/practices, 4.9% (n=3) indicated sex with another man.

Table 2.3. Number and rate of deaths with hepatitis A listed as a cause of death, by demographic characteristics and year — United States, 2004–2008

- In 2008, the mortality rate of hepatitis A was 0.02 per 100,000 population (n=83).

- During all 5 years, mortality rates were highest among persons aged ≥75 years compared with other age groups (in 2008 the rate was 0.12 deaths per 100,000 population).

- In 2008, hepatitis A mortality rates were similar among blacks and non-whites/non-blacks; persons whose race was classified as white had lower rates.

- From 2004 through 2008, the hepatitis A mortality rate was consistently higher among males than among females.

Acute Hepatitis B

In 2010, a total of 3,350 acute cases of hepatitis B were reported nationwide to CDC (Table 3.1). The overall incidence rate for 2010 was 1.1 cases per 100,000 population, ranging from no cases in Montana to 4.7 cases per 100,000 population in West Virginia. After adjusting for asymptomatic infections and under-reporting, the estimated number of new HBV infections in 2010 was 35,000 (see Estimation Procedures).

Table 3.1. Reported cases of acute hepatitis B, nationally and by state ― United States, 2006–2010

- The number of acute cases of hepatitis B decreased by 29% overall during 2006–2010, from 4,713 cases to 3,350 cases.

- Of the 48 states that reported acute hepatitis B cases in 2010, 27 had rates below the national rate of 1.1 per 100,000 population.

- Rates of reported acute hepatitis B cases in 2010 ranged from 0 cases (Montana) to 4.7 cases per 100,000 population (West Virginia).

Table 3.2. Clinical characteristics of reported cases of acute hepatitis B ― United States, 2010

- Of the 3,350 case reports of acute hepatitis B received in 2010, 55.0% included information regarding whether the patient had jaundice, 60.1% had information regarding hospitalization caused by hepatitis B, and 55.9% included data for hepatitis B-associated deaths.

- In 2010, of all case reports with information about clinical characteristics,

- 76.7% indicated the patient had jaundice;

- 49.8% indicated the patient was hospitalized as a result of hepatitis B; and

- 1.5% indicated the patient died from hepatitis B.

Figure 3.1. Reported number of acute hepatitis B cases — United States, 2000–2010

- The number of reported cases of acute hepatitis B decreased 58.3%, from 8,036 in 2000 to 3,350 in 2010.

Figure 3.2. Incidence of acute hepatitis B, by age group — United States, 2000–2010

- The incidence of acute hepatitis B declined in all age groups.

- In 2010,

- the highest rate was among persons aged 30–39 years (2.33 cases/100,000 population),

- the lowest rate was among adolescents and children aged <19 years (0.06 cases/100,000 population).

Figure 3.3. Incidence of acute hepatitis B, by sex — United States, 2000–2010

- Incidence rates of acute hepatitis B decreased for both males and females from 2000 through 2009, and appeared stable through 2010.

- The gap in acute hepatitis B incidence rates between males and females narrowed between 2000 and 2010.

- In 2010, the rate for males was approximately 1.6 times higher than that for females (1.36 cases and 0.83 cases per 100, 000 population, respectively).

Figure 3.4. Incidence of acute hepatitis B, by race/ethnicity — United States, 2000–2010

- The incidence rate of acute hepatitis B was <4.3 cases per 100,000 population for all race/ethnic populations from 2002 through 2010.

- In 2010, the rate of acute hepatitis B was lowest for APIs and Hispanics (0.6 cases per 100,000 population for each group) and highest for non-Hispanic blacks (1.7 cases per 100,000 population).

Figure 3.5. Distribution of risk behaviors/exposures associated with acute hepatitis B — United States, 2010

- Of the 3,350 case reports of acute hepatitis B received by CDC during 2010, a total of 1,566 (47%) did not include a response (i.e., a “yes” or “no” response to any of the questions about risk behaviors and exposures) to enable assessment of risk behaviors or exposures.

- Of the 1,784 case reports that had complete information, 63.5% (n=1,133) indicated no risk behaviors/exposures for hepatitis B, and 36.4% (n=651) indicated at least one risk behavior/exposure for hepatitis B during the 6 weeks to 6 months prior to illness onset.

Figure 3.6a. and Figure 3.6b. Reported cases of acute hepatitis B, by risk behavior/exposure — United States, 2010

Patients were asked about engagement in selected risk behaviors and exposures during the incubation period, 6 weeks to 6 months prior to onset of symptoms.

- Of the 1,459 case reports that contained information about occupational exposures, 0.7% (n=10) indicated employment in a medical, dental, or other field involving contact with human blood.

- Of the 1,129 case reports that included information about receipt of dialysis or kidney transplant, 0.4% (n=4) reported receipt of dialysis or a kidney transplant.

- Of the 1,378 case reports that had information about receipt of blood transfusion, 0.4% (n=6) noted receipt of a blood transfusion.

- Of the 1,333 case reports that had information about recent surgery, 9.8% (n=131) reported such surgery.

- Of the 1,295 case reports that had information about needlesticks, 4.2% (n=54) reported a needlestick.

- Of the 1,251 case reports that had information about injection-drug use, 15.8% (n=198) noted use of these drugs.

- Of the 922 case reports that had information about sexual contact, 8.0% (n=74) indicated sexual contact with a person with confirmed or suspected hepatitis B infection.

- Of the 244 case reports from males that included information about sexual preference/practices, 17.2% (n=42) indicated sex with another man.

- Of the 948 case reports that had information about number of sex partners, 28.0% (n=265) were among persons with ≥2 sex partners.

- Of the 922 case reports that had information about household contact, 2.0% (n=18) indicated household contact with someone with confirmed or suspected hepatitis B infection.

Chronic Hepatitis B

Table 3.3. Number of laboratory-confirmed, chronic hepatitis B* case reports† — National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS), 2010

- 11 states agreed to publication of NNDSS data for chronic hepatitis B in 2010.

- In 2010, the greatest number of reports was received from Massachusetts (n=614), representing 28.3% of the 2,168 reports; the least number of reports was received from Wyoming (n=24).

Table 3.4. Reported cases of laboratory-confirmed, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and case criteria — Enhanced Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Sites, 2010

- A total of 10,515 chronic hepatitis B cases were reported by eight sites in 2010.

- New York City reported the greatest number of cases (n=7,286; 69.3%) compared with other sites.

- San Francisco reported the highest rate of chronic HBV infection, with 110 cases per 100,000 population.

- The percentage of male cases at the six sites ranged from 48% – 57%.

- Among cases for whom race/ethnicity was known, Asian/Pacific Islanders accounted for the highest proportion of chronic HBV cases reported from all sites.

- For all sites, the highest proportion of cases (n=7,470; 62.5%) were among persons aged 25–54 years.

- HBsAg was the most common HBV laboratory marker used to confirm a case of chronic hepatitis B (83.4%); however, HBV DNA positive test results were also reported for 60.2% of cases.

Table 3.5. Number and rate of deaths with hepatitis B listed as a cause of death, by demographic characteristics and year — United States, 2004–2008

- From 2004–2008, hepatitis B accounted for more deaths than hepatitis A but fewer deaths than hepatitis C.

- In 2008, the mortality rate for hepatitis B was 0.5 deaths per 100,000 population (n=1,788).

- From 2007–2008, mortality rates were highest among persons aged 55–64 years compared with other age groups (in 2008 the rate was 1.6 deaths per 100,000 population).

- From 2004–2007, the mortality rate increased among persons aged 55–64 years, from 1.4 deaths per 100,000 population in 2004 to 1.7 deaths per 100,000 population in 2007 and then decreased slightly to 1.6 deaths per 100,000 population in 2008.

- In 2008, the highest mortality rates were observed among persons aged 55–64 years (1.6 deaths per 100,000 population), among those in the “non-white, non-black” race category (2.1 deaths per 100,000 population), and among males (0.9 deaths per 100,000 population).

Acute Hepatitis C

In 2010, a total of 40 states and the District of Columbia submitted 850 reports of acute hepatitis C to CDC (Table 4.1). The incidence rate for 2010 was 0.3 cases per 100,000 population and has increased approximately 6% since 2006. After adjusting for asymptomatic infections and underreporting, an estimated 17,000 new infections of HCV occurred in 2010 (see Estimation Procedures).

Table 4.1. Reported cases of acute hepatitis C, nationally and by state ― United States, 2006–2010

- The number of acute cases of hepatitis C reported in the United States increased about 6%, from 802 in 2006 to 850 in 2010.

- The national rate of acute cases of hepatitis C remained stable, at 0.3 cases per 100,000 population from 2006 through 2010.

- Of the 40 states and the District of Columbia that submitted reports of acute hepatitis C in 2010, 14 states had rates below the national rate (0.3 cases per 100,000 population).

- Rates of acute hepatitis C ranged from 0 cases per 100,000 population (Arkansas, Illinois, and South Carolina) to 2.5 cases per 100,000 population (Kentucky).

Table 4.2. Clinical characteristics of reported cases of acute hepatitis C ― United States, 2010

- Of the 850 case reports of acute hepatitis C received in 2010, 65.6% included information regarding whether the patient had jaundice, 67.9% had data regarding hospitalization caused by hepatitis C, and 59.6% included data for hepatitis C-associated deaths.

- In 2010, of all case reports with information regarding clinical characteristics,

- 74.4% indicated the patient had jaundice;

- 57.5% indicated the patient was hospitalized as a result of hepatitis C;

- 0.6% indicated the patient died from hepatitis C.

Figure 4.1. Reported number of acute hepatitis C cases — United States, 2000–2010

- The number of reported cases of acute hepatitis C declined rapidly through 2002 and has remained relatively stable for the past 8 years.

Figure 4.2. Incidence of acute hepatitis C, by age group — United States, 2000–2010

- Prior to 2002, incidence rates for acute hepatitis C decreased for all age groups (excluding the 0–19 year age group); rates remained fairly constant from 2002 through 2010.

- In 2010, rates were highest among persons aged 20–29 years (0.8 cases per 100,000 population) and lowest among persons 0-19 and ≥60 years of age (<0.1 cases per 100,000 population).

Figure 4.3. Incidence of acute hepatitis C, by sex — United States, 2000–2010

- Incidence rates of acute hepatitis C decreased dramatically for both males and females through 2003 and remained relatively stable from 2004 through 2010.

- Rates for males declined faster than rates for females and by 2004, the rates were nearly equal.

- In 2010, rates for males and females were both estimated at 0.3 cases per 100,000 population.

Figure 4.4. Incidence of acute hepatitis C, by race/ethnicity — United States, 2000–2010

- Rates for acute hepatitis C decreased for all racial/ethnic populations through 2003.

- During 2002–2010, the incidence rate of acute hepatitis C remained below 0.5 cases per 100,000 for all racial/ethnic populations except AI/ANs.

- In 2010 the rate for hepatitis C was lowest among APIs (0 cases per 100,000 population) and highest among AI/ANs (0.5 case per 100,000 population).

Figure 4.5. Distribution of risk behaviors/exposures associated with acute hepatitis C — United States, 2010

- Of the 850 case reports of acute hepatitis C received by CDC during 2010, 324 (38%) did not include a response (i.e., a “yes” or “no” response to any of the questions about risk behaviors and exposures) to enable assessment of risk behaviors or exposures.

- Of the 522 (61%) case reports that had complete information, 38% (n=198) indicated no risk behaviors/exposures for hepatitis C infection, and 62% (n=324) indicated at least one risk behavior/exposure for hepatitis C infection during the 6 weeks to 6 months prior to illness onset.

Figure 4.6a. and Figure 4.6b. Reported cases of acute hepatitis C, by risk behavior/exposure — United States, 2010

Patients were asked about engagement in selected risk behaviors and exposures during the incubation period, 2 weeks to 6 months prior to onset of symptoms.

- Of the 413 case reports that contained information about occupational exposures, 1.7% (n=7) involved persons employed in a medical, dental, or other field involving contact with human blood.

- Of the 321 case reports that had information about receipt of dialysis or a kidney transplant, 0.3% (n=1) indicated patient receipt of dialysis or a kidney transplant.

- Of the 320 case reports that had information about surgery, 12.2% (n=39) were among persons who had undergone surgery.

- Of the 325 case reports that included information about needle sticks, 7.7% (n=25) indicated accidental needle stick/puncture.

- Of the 381 case reports that had information about injection-drug use, 53.0% (n=202) noted use of these drugs.

- Of the 68 case reports from males that included information about sexual preferences/practices, 10.3% (n=7) indicated sex with another man.

- Of the 117 case reports that had information about sexual contact, 17.9% (n=21) involved persons reporting sexual contact with a person with confirmed or suspected hepatitis C infection.

- Of the 328 case reports that had information about number of sex partners, 33.2% (n=109) involved persons with ≥2 sex partners.

- Of the 117 case reports that had information about household contact, 1.7% (n=2) indicated household contact with someone with confirmed or suspected hepatitis C infection.

Hepatitis C, past or present

Table 4.3. Number of laboratory confirmed, chronic (past or present) hepatitis C case reports — National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS), 2010

- 8 states agreed to publication of their NNDSS data for chronic hepatitis C in 2010.

- Of the 8 states, the greatest number of reports was received from New Jersey (n=6,972), representing 26.8% of the 25,974 approved reports; the least number of reports was received from South Dakota (n=349).

Table 4.4. Reported cases of laboratory-confirmed, chronic (past or present) hepatitis C infection, by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and case criteria — Enhanced Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Sites, 2010

- A total of 33,699 chronic hepatitis C cases were reported by eight sites.

- More cases were reported by New York City (n=10,021; 29.7%) compared with other sites.

- San Francisco had the highest rate of chronic HCV infection, with 210 cases per 100,000 population.

- Overall, two-thirds (64.7%) of reported cases were among males. In each site, males made up at least 60% of all cases.

- Among all cases for whom race/ethnicity was known, non-Hispanic whites accounted for the highest proportion (25.6%) of chronic HCV case reports.

- Among all cases, 40.6% were among persons aged 40–54 years.

- Cases were most frequently reported with a positive anti-HCV test and high signal-to-cutoff ratio (52.5%); however, RNA was reported among 45.7% of cases.

Table 4.5. Number and rate of deaths with hepatitis C listed as a cause of death, by demographic characteristics and year — United States, 2004–2008.

- Of the three types of viral hepatitis (hepatitis A, B, and C), hepatitis C accounted for the most deaths and had the highest death rate.

- From 2004 through 2008, the mortality rate of hepatitis C increased from 3.7 deaths per 100,000 population in 2004 to 4.7 deaths per 100,000 population in 2008.

- From 2004 through 2006, the highest mortality rates were observed among persons aged 45–54 years.

- In 2007 and 2008, the highest mortality rates (15.7 and 17.7 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively) were observed for persons aged 55–64 years.

- From 2004 through 2008, the highest mortality rates were observed among blacks (range 6.5- 7.8 deaths per 100,000 population) and males (range 5.4-6.8 deaths per 100,000 population).

Discussion

National surveillance data for viral hepatitis provide essential information for developing prevention strategies and monitoring their effectiveness. National rates for acute hepatitis A and B have been published since 1966, and national rates for acute hepatitis C/non-A, non-B have been published since 1992. Major changes in the epidemiology of these diseases have occurred over these time periods, largely resulting from implementation of prevention strategies for each disease, including the introduction of effective vaccines against hepatitis A and hepatitis B.

Nationally notifiable diseases data are collected and compiled from reports sent voluntarily by state health departments, the District of Columbia, and territories to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). Although NNDSS represents the core of viral hepatitis surveillance, disease reporting is likely incomplete and can vary by jurisdiction. To better count and characterize cases of viral hepatitis and estimate the burden of disease, CDC currently supplements NNDSS data with those obtained from select enhanced surveillance sites, national surveys, and vital statistics.

Data from NNDSS indicate declining rates of acute hepatitis A and acute hepatitis B during 2006 –2009; rates of acute hepatitis C were stable. However, new infections with HAV, HBV, and HCV remain common. In 2010, after adjusting for asymptomatic cases and underreporting, the estimated incidence of HAV, HBV, and HCV infections was 17,000, 35,000, and 17,000 cases, respectively. Despite decreases in acute viral hepatitis, chronic infection continues to affect millions of Americans. In the United States, an estimated 805,000–1.4 million persons are living with chronic hepatitis B infection (1), and an estimated 2.7–3.9 million persons are chronically infected with hepatitis C (2).

In 2010, CDC received 2,168 reports of chronic hepatitis B infection confirmed by 11 states and 25,974 reports of chronic hepatitis C infections confirmed by 8 states. An additional 10,515 case reports of chronic hepatitis B and 32,587 case reports of chronic hepatitis C were received from 8 enhanced surveillance sites during the same year.

Trends in mortality data from 1999-2007 reveal the serious health consequences associated with viral hepatitis. Deaths from HCV increased such that the number exceeded deaths from HIV infection (3). In 2008, viral-hepatitis-associated death rates were highest among persons infected with HCV (4.7 deaths per 100,000 population), followed by HBV (0.5 deaths per 100,000 population), and HAV (0.02 deaths per 100,000 population).

CDC and state health departments rely on surveillance data to track the incidence of acute infection, guide development and evaluation of programs and policies designed to prevent infection and minimize the public health impact of viral hepatitis and related disease, and monitor progress towards achieving goals established for these programs and policies. Effective systems for conducting surveillance for chronic HBV and HCV infections are needed to ensure accurate reporting of all cases and to support and evaluate prevention activities. Additional investments in surveillance at the local, state, and national levels are essential to building strong prevention programs that interrupt transmission of viral hepatitis and improve the health of persons living with viral hepatitis.

References

- Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR 2008;57(RR-8):2

- Armstrong GL, Wasley AM, Simard EP, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:705–14.

- Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:271-8.

Additional Resources

Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. The Pink Book: Course Textbook. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/index.html

Hepatitis A: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/hepa.pdf [PDF – 14 Pages]

Hepatitis B: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/hepb.pdf [PDF – 24 Pages]

Viral Hepatitis Outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Outbreaks/index.htm

Prevention of Hepatitis A through Active or Passive Immunization: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP): https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5507.pdf [PDF – 30 Pages]

A Comprehensive Immunization Strategy to Eliminate Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States — Part I: Immunization of Infants, Children, and Adolescents: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5416.pdf [PDF – 39 Pages]

A Comprehensive Immunization Strategy to Eliminate Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States — Part II: Immunization of Adults: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5516.pdf [PDF – 40 Pages]

Recommendations for Identification and Public Health Management of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5708.pdf [PDF – 28 Pages]

Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection and HCV-Related Chronic Disease: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/RR/RR4719.pdf [PDF – 54 Pages]

2005 Guidelines for Viral Hepatitis Surveillance and Case Management: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics/SurveillanceGuidelines.htm