Cluster Review and Prioritization

Reviewing and prioritizing clusters can help health departments understand the level of investigation and response needed. It can also help determine where to focus resources.

Convene group to review and prioritize clusters

Health departments should convene a CDR leadership and coordination group (LCG) to review and prioritize clusters. The group should meet at least monthly, unless there are no new clusters and no clusters being monitored, and should:

- Review available data

- Prioritize clusters

- Determine the amount and type of additional information needed to guide response

- Decide on and implement response actions

The CDR LCG can scale response activities up or down based on their level of concern, local epidemiology, and available capacity and resources. During scaled up response activities, consider including additional staff in CDR LCG meetings. CDC can also provide technical assistance with prioritizing clusters. Health departments should contact their assigned Detection and Response Branch epidemiologists for assistance.

Compile and review available data

Health departments should compile and review data from multiple sources to determine their level of concern. The potential for cluster growth and negative health outcomes are important factors in prioritizing clusters for response. Health departments can use their comprehensive HIV CDR plan to guide the review process. The plan should include which staff will lead the process and which data sources are available.

Monitoring and reviewing clusters should be an ongoing process. New information collected during an investigation and response might change the level of concern. During review, health departments can consider which response approaches to prioritize to improve HIV care and prevention and reduce transmission. Ongoing review will also help determine whether a cluster response should continue. Even after response efforts end, continued monitoring can determine whether response efforts should resume.

Cluster case definition

When planning to review and prioritize a cluster, it is helpful to create a cluster case definition. A cluster case definition describes specific criteria for including someone in a cluster. Criteria can include a variety of information, such as year of diagnosis, race or ethnicity, or geographic area. A cluster case definition helps with estimating and assessing the cluster’s size and growth, and prioritizing response.

Cluster case definitions can be especially important for time-space clusters because the inclusion criteria are often less specific than for molecular clusters. Cluster case definitions are also helpful for molecular clusters. In this case, they can include people who are part of a network but not identified in the molecular cluster. Cluster case definitions may change as more data become available.

Example Cluster Case Definitions

- Molecular cluster case definition: A person with a confirmed HIV diagnosis on or after January 1, 20XX who:

- is a member of XXX molecular HIV cluster using a 0.5% genetic distance threshold; OR

- has had sex or shared drug injection equipment with a cluster member.

- Time-space cluster case definition: Confirmed HIV diagnosis on or after January 1, 20XX in a person who:

- has a history of injection drug use; AND

- lived in X county at the time of diagnosis; AND

- has had sex or shared drug injection equipment with a cluster member.

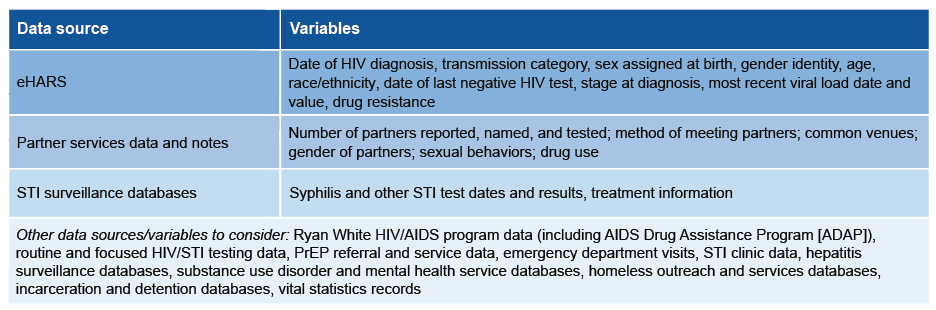

Data sources

Relevant data sources include HIV surveillance, prevention, and care; partner services; sexually transmitted infections (STI); and other related program data. Health departments should have a plan to securely compile the existing data. This can be done manually or by creating a process or product that automatically combines data from different sources. Health departments can implement a dashboard or other method that allows for analysis, integration, visualization, and secure data sharing. Because compiling data can be complex, staff might need to consult with their data management or IT programs for support.

Examples of Data Sources and Variables to Include During Review

Summarize cluster data

Once the data are compiled, the CDR LCG should review and discuss the information. Consider creating a narrative description or a line list for the cluster to summarize the data.

Cluster narrative

It is often helpful to create a narrative from the compiled data to better understand the network, what people in the cluster have in common, and what additional information would be most useful. This can help guide cluster prioritization.

Example Cluster Narrative

- We identified a molecular cluster of 12 people with HIV, within the 18-month period ending December 2023. The cluster primarily included young Black gay and bisexual men in a rural part of State X. Among people in the cluster:

- 7 of 12 people with testing history data have evidence of infection within 12 months of diagnosis.

- All sequences have K103N mutation.

- 6 of 12 people have no evidence of viral suppression.

- Partner services conducted for 8 of 12 people in the molecular cluster identified 3 named partners: 1 person with newly diagnosed HIV, 1 person with previously diagnosed HIV, and 1 person who tested negative.

- People in the cluster identified large numbers of anonymous or marginal partners. Multiple cluster members identified a dating app X as the primary way they meet partners.

- The scope of the cluster and network are likely much larger than identified through molecular analysis and available partner services information.

Line lists

Line lists are tables with key information about each person in a cluster or associated network. Typically, each row represents one person, and each column represents the data variables included in the review process. This helps summarize information and guide prioritization. However, health departments must limit access to ensure that individual-level information is not shared inappropriately. Even line lists that don’t include personally identifiable information can include sensitive information.

Prioritize clusters for response

Once the data have been summarized, health departments should prioritize clusters to determine whether investigation and response is warranted. The questions to consider may vary depending on how cluster detection occurred—through time-space analysis, molecular detection, or other methods. Health departments should prepare criteria in advance to guide prioritization and describe potential investigation and response actions.

Questions to consider when developing prioritization criteria

What is the local epidemiology?

Factors to consider include:

- How significant is the increase in new diagnoses compared to the baseline?

- Are diagnoses occurring in a certain geographic area?

Are there alternative explanations for an increase in diagnoses?

This is important for clusters detected through time-space or other non-molecular methods. Consider other potential reasons for observed increases in diagnoses, such as:

- Changes in data quality

- Increases in testing

- Demographic changes

- Policy changes

What is the potential for ongoing transmission?

Factors that raise concern for ongoing transmission include:

- Social determinants of health that might limit access to HIV prevention and care (for example, unstable housing, history of incarceration)

- Injection drug use

- Large numbers of sex partners

- People who have high viral loads or are not in care

- Multiple people who have acquired HIV recently (for example, acute or stage 0 infection at diagnosis)

- Limited or inadequate HIV prevention and care services in the area

- Coinfection with other STIs or hepatitis

Is there a strong understanding of the network involved in this cluster?

Further investigation may be warranted if:

- The health department is experiencing challenges interviewing people in clusters and conducting partner services

- People in clusters report large numbers of anonymous partners

- HIV testing is limited, suggesting that the network is substantially larger than what has been detected

- For molecular clusters, sequence completeness is low, meaning the cluster is likely much larger than it appears

Do people in the cluster have the potential of experiencing poor health outcomes?

Factors that can indicate potential for poor health outcomes among cluster members include:

- Medically underserved populations (for example, youth or people experiencing homelessness)

- People experiencing discrimination due to race or ethnicity, sexual or gender identity, or immigration status

- Women of child-bearing age

- Late diagnoses due to limited testing and care access

- Diagnoses at locations such as emergency departments or correctional institutions

- Identified HIV drug resistance

The CDR LCG should establish, implement, and revise criteria for levels of concern and associated responses.

Clusters and networks often cross jurisdictional borders. Someone may live in one jurisdiction and have partners or seek care elsewhere. Cluster review, investigation, and response should include all people linked to the network, regardless of where they live. This may require collaboration across multiple health departments.

Ongoing reporting, review, and prioritization

The CDR LCG should discuss and review clusters at least monthly. As more data become available, clusters may increase or decrease in priority. As the priority level for a cluster changes, investigation and response can be scaled up or down. Low-priority clusters may warrant monitoring even if they do not need active investigation and response efforts initially.

Health departments should report cluster investigation and response activities to CDC by submitting cluster report forms (CRFs) quarterly. These forms can facilitate structured communication with Detection and Response Branch epidemiologists about ongoing response efforts. These reports are also important for national evaluation of CDR. If a cluster remains consistently low priority over time, the health department can end response activities and stop submitting CRFs.