Continue to check our website for further updates on when we will reopen. When the museum reopens, all visitors will need to make reservations at least a week in advance. Walk-in visits are no longer permitted.

Teen Newsletter: Asthma

December 2022

The David J. Sencer CDC Museum (CDCM) Public Health Academy Teen Newsletter was created to introduce teens to public health topics. Each newsletter focuses on a different public health topic that CDC studies. Newsletter sections include: Introduction, CDC’s Work, The Public Health Approach, Out of the CDC Museum Collection, and Teen Talk.

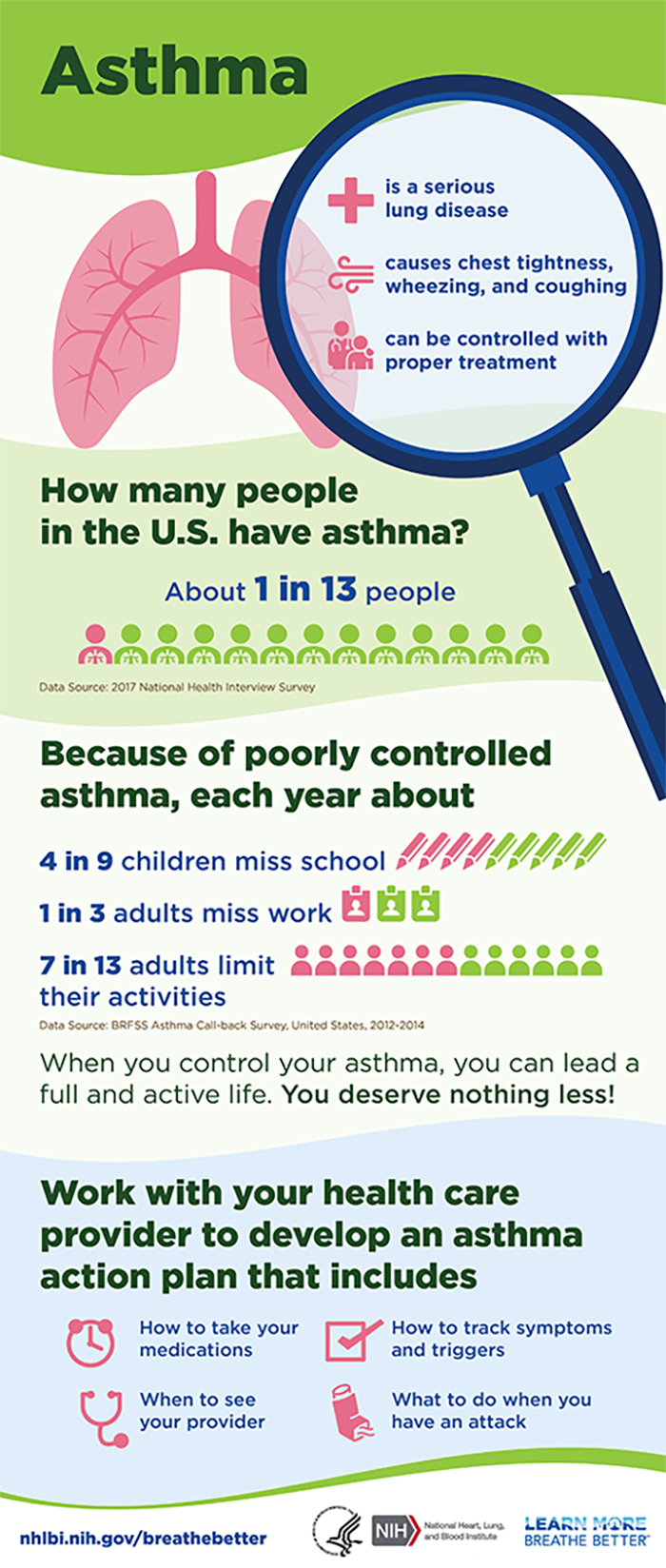

Asthma is a chronic disease that affects the airways in the lungs. It causes repeated episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and nighttime or early morning coughing. During an asthma attack, airways become inflamed, making it hard to breathe. Asthma attacks can be mild, moderate, or severe—and even life-threatening. It is one of the most common long-term diseases of children, but adults can have asthma, too.

An asthma attack happens in the airways that carry air to your lungs. During an asthma attack, the sides of the airways in your lungs swell and the airways shrink. Less air gets in and out of your lungs, and mucous that your body makes clogs up the airways, making it harder and harder to breathe.

An asthma attack can happen when you are exposed to “asthma triggers.” The most common triggers are tobacco smoke, dust mites, outdoor air pollution, cockroach allergen, pets, mold, smoke from burning wood or grass, and infections like flu.

Genetic, environmental, and occupational factors have been linked to a person developing asthma. If someone in your immediate family has asthma, you are more likely to have it.

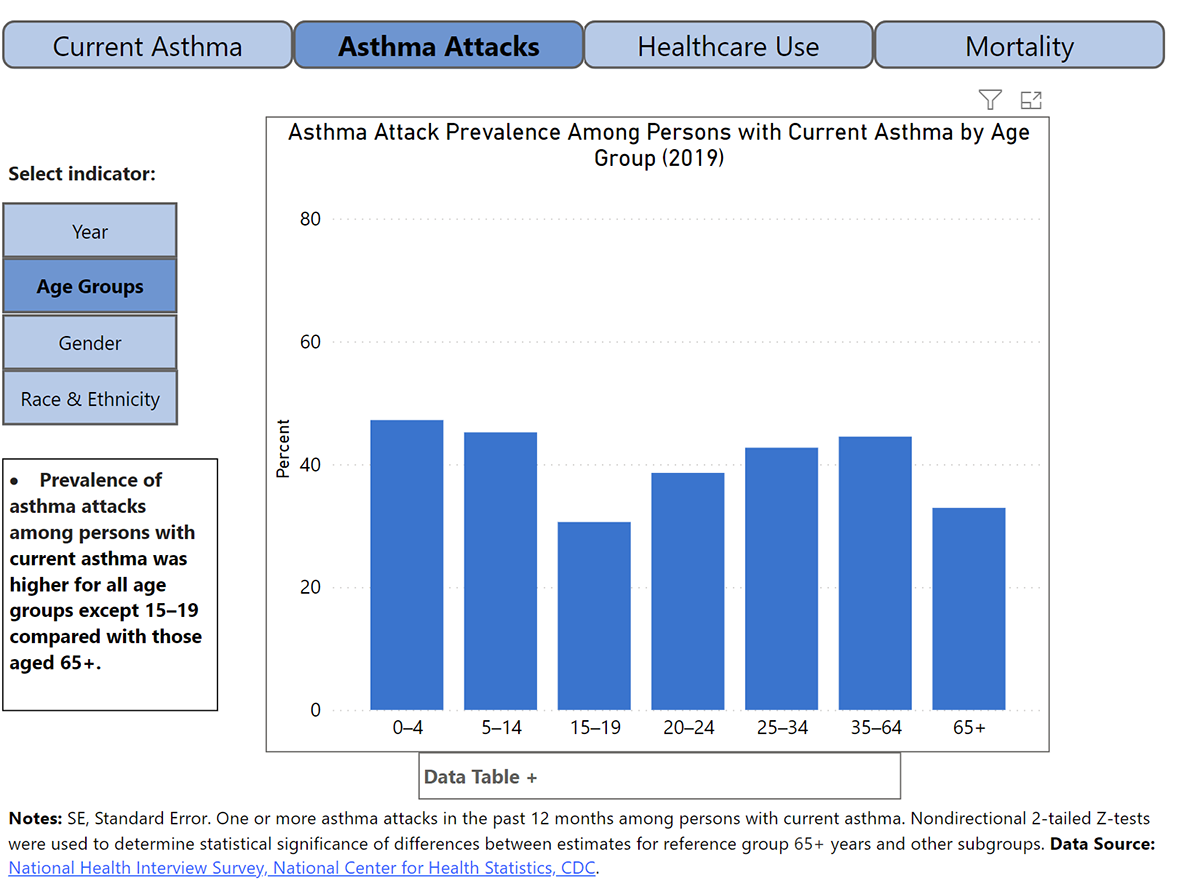

Asthma is one of many health disparities for minorities. About 16% of Black children and 7% of White children have asthma. Black children are twice as likely to have asthma compared to White children. In 2016, children ages 0-4 years and non-Hispanic Black children were most likely to visit the emergency department and urgent care centers due to asthma attacks.

Asthma has had a tremendous economic impact. From 2002-2007, medical expenditures due to asthma hospitalizations and emergency room visits increased from $48.6 billion to $50.1 billion or about $3,300 per person with asthma each year. When indirect costs due to days missed at school and work are factored in, that number climbs to $56 billion. In 2013, the total cost of asthma, including costs incurred by missing school or work and mortality, climbed to $81.9 billion.

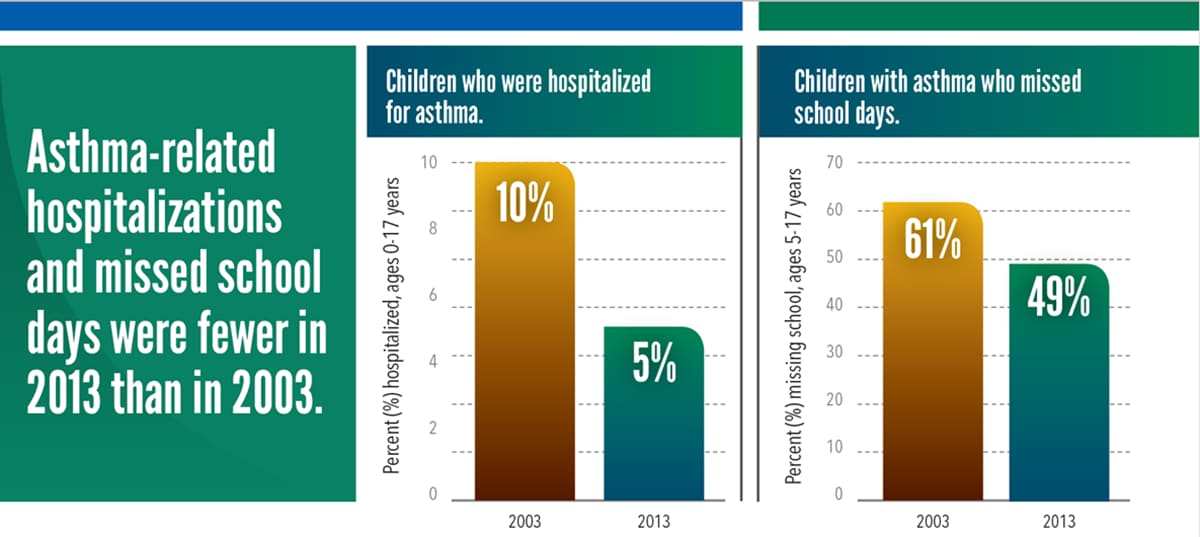

Despite all of these concerning statistics, there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic. Today, children with asthma and their caregivers report fewer attacks, missed school days, and hospital visits. More children with asthma are learning to control their asthma using an asthma action plan. Still, more than half of children with asthma had one or more attacks in 2016. Every year, 1 in 6 children with asthma visits the emergency department with about 1 in 20 children with asthma hospitalized for asthma.

There are three centers at CDC that work on asthma

- The National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH) protects the American people from environmental hazards by promoting a healthy environment and preventing premature death, avoidable illness, and disability caused by environmental and related factors. The Asthma and Community Health branch of NCEH focuses on asthma, air quality, carbon monoxide poisoning, climate and health, mold, and wildfires. The Environmental Public Health Tracking Program tracks asthma hospital stays, emergency department visits for asthma, and asthma prevalence (the number of people diagnosed with and living with asthma).

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) studies worker safety and health. NIOSH conducts asthma research and prevention of work-related asthma studies to better understand work-exacerbated asthma and contribute to the prevention of work-related asthma.

- CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) helps people and communities prevent chronic diseases and promotes health and wellness for all. Through collaboration with the Division of Population Health (DPH), CDC’s NCCDPHP measures and reports how asthma and asthma risk factors affect individuals and populations in the United States.

Public health problems are diverse and can include infectious diseases, chronic diseases, emergencies, injuries, environmental health problems, as well as other health threats. Regardless of the topic, we take the same systematic, science-based approach to a public health problem by following four general steps.

Due to the prevalence and potential lethality of asthma, it is important for heavy surveillance, risk factor identification, intervention evaluation, and implementation of the interventions to be put in place. Many surveys have been performed to carry out this task, and they have shown that children are far more likely to have asthma than any other age group. This section will explain how the Wee Wheezers Asthma Education program assists parents to meet the needs of their asthmatic children.

- Surveillance (What is the problem?). In public health, we identify the problem by using surveillance systems to monitor health events and behaviors occurring among a population.

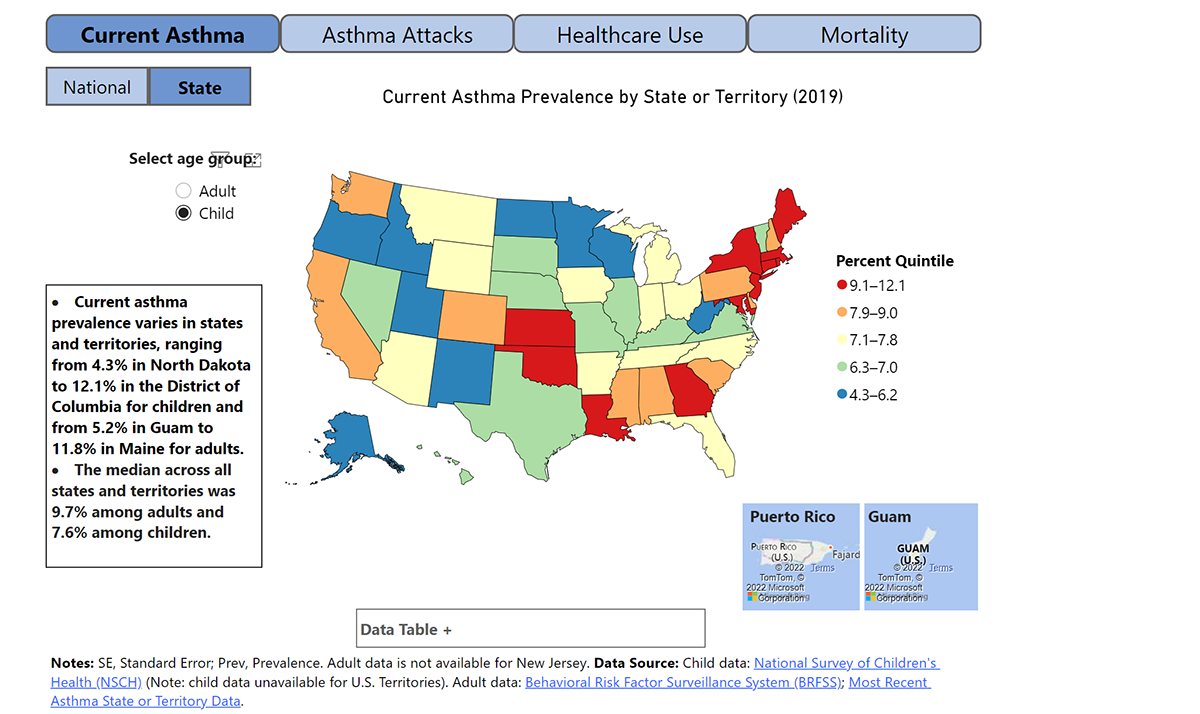

Since 1997, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) has gathered information about lifetime asthma and asthma attacks or episodes from the Sample Adult Core and Sample Child Core questionnaires. The survey asks questions like, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had asthma? During the past 12 months, have you had an episode of asthma or an asthma attack? Do you still have asthma?” This allows researchers to determine rates of asthma, prevalence of asthma episodes or attacks, and ongoing asthma. Results showed that current asthma was higher among boys aged <18 years, women aged ≥18 years, non-Hispanic Black persons, non-Hispanic multiple-race persons, and Puerto Rican persons. Furthermore, asthma attacks were more prevalent among children, females, and multiple-race persons. All asthma-related outcomes were prevalent among lower-income families.

- Risk Factor Identification (What is the cause?). After we’ve identified the problem, the next question is, “What is the cause of the problem?” For example, are there factors that might make certain populations more susceptible to diseases, such as something in the environment or certain behaviors that people are practicing?

Socioeconomic and demographic factors as well as health care use might influence health patterns in urban and rural areas related to asthma (Reporting Period: 2006–2018). Risk factors for developing asthma include poverty status, the education level of parents, location, smoking or being in the presence of smokers, and access to medical care/coverage. Pre- and post-natal exposures to cigarette smoking are associated with asthma and asthma morbidity in childhood. In utero smoke exposure varies widely among ethnic minorities: 20% in American Indians, 16% in Whites, 10% in Puerto Ricans and non-Hispanic blacks, 5% in Japanese, 3% Mexicans, and 1.5% in Central/South Americans. In utero smoke exposure also varies by insurance type and education status. During childhood, the prevalence of tobacco smoke exposure is higher in children with asthma symptoms and doctor-diagnosed asthma, with a larger difference in children from lower socio-economic status. Smoke exposure increases asthma morbidity. Smoke-free laws have been associated with fewer asthma ER visits both in children and in adults.

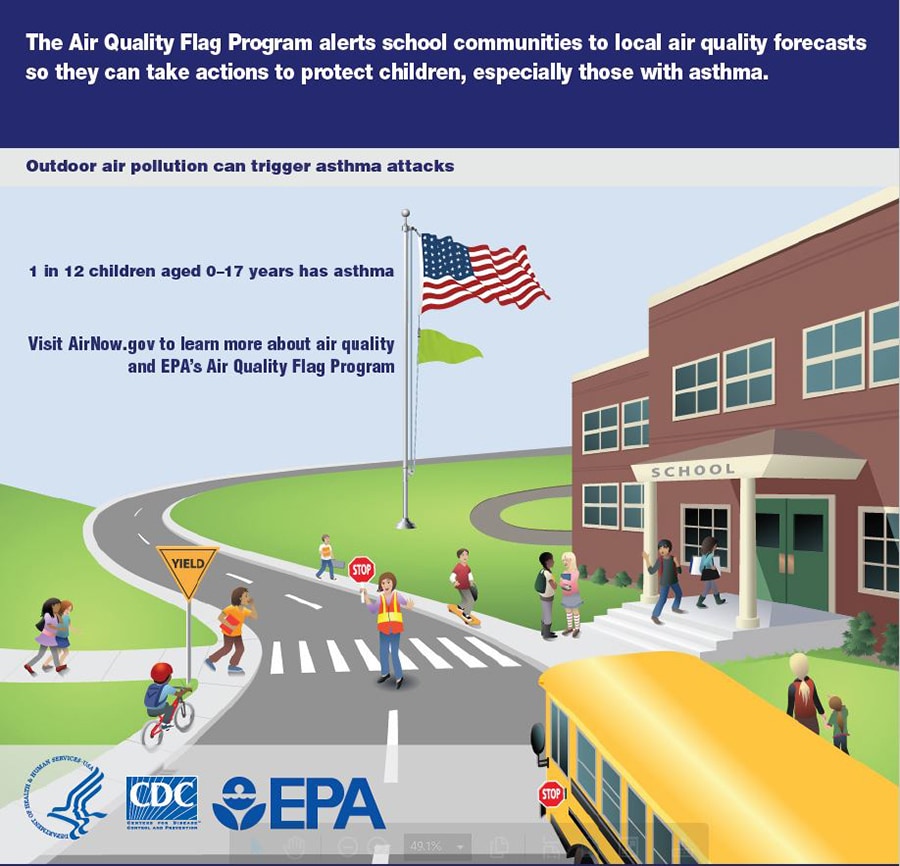

Outdoor pollutants can trigger asthma exacerbations and may play a role in developing asthma. Non-whites are more likely to live in areas with elevated levels of air pollutants, including particulates, carbon monoxide, ozone and sulfur dioxide. A study in New York City showed higher rates of asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations in children from highly polluted areas such as the Bronx, which also has a high percentage of residents from minority populations.

Many families of very young children experience significant stress related to the child’s asthma. Families need help in coping with the asthma when the disease first becomes apparent.

- Intervention Evaluation (What works?). Once we’ve identified the risk factors related to the problem, we ask, “What intervention works to address the problem?” We look at what has worked in the past in addressing this same problem and if a proposed intervention makes sense with our affected population.

As part of CDC’s National Asthma Control Program (NACP), CDC funds 25 state, territorial, and municipal health departments to improve the quality of asthma care and management. Through NACP, the Wee Wheezers Asthma Education Program was implemented in Ft. Hood, Texas. The program grew out of original asthma research, and it has been fully developed into a complete educational package. The program targets parents of children under the age of seven years who have asthma. It is designed as a community-based asthma initiative. Through this program, several of the following risk factors were identified that relate to ineffective asthma management practices of parents of asthmatic children:

- Denial of the child’s illness by one or both parents

- Fear about routine use of medications

- Not avoiding common asthma triggers, such as pet dander

- lacking awareness on asthma management, causing the family and parents to experience significant stress for managing the child’s asthma

To address some of these risk factors, the program provided educational lessons and included participant feedback and discussion about their experiences with asthma. The program had homework assignments to help engage parents in learning activities that support becoming effective managers of their child’s asthma. Additionally, children received asthma education, preparing them to effectively manage their disease. Homework for children included practicing belly breathing and completing an asthma diary with their parents’ assistance. In the diary, they recorded taking medications, informing a parent when they were having an asthma symptom, doing belly breathing, and recording peak flow results. Lastly, the program included an evaluation form to be completed by the instructors and course participants. The results of this evaluation were used to document and assess the need for course improvements.

Successful results reported from the Wee Wheezers program were 1) reductions in the number of hospitalizations; 2) reductions in the number of emergency department visits for asthma; 3) improvement in the affected child’s quality of life as reported by the family; 4) cost-savings to the community hospital resulting from better asthma patient self-management.

- Implementation (How did we do it?). In the last step, we ask, “How can we implement the intervention? Given the resources we have and what we know about the affected population, will this work?”

Initially, the Wee Wheezers Asthma Education Program was established in Darnell Army Community Hospital, Ft. Hood, Texas. However, the program has rapidly spread and has now been implemented in hospitals, clinics, and primary care physicians’ offices. The shift in expanding the program to additional locations represents the program’s primary goal of delivering the Wee Wheezers Program’s educational materials to a large number of children with asthma and their parents. As many of the program’s staff include department chiefs, the program has combined patient education with new standards for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma as well as improving asthma care for families. The Wee Wheezers Program was implemented as a large-scale educational program modeling a community-based public health intervention. It was reported as a successful intervention that showed improvements in asthma care and treatment.

Using The Public Health Approach helps public health professionals identify a problem, find out what is causing it, and determine what solutions/interventions work.

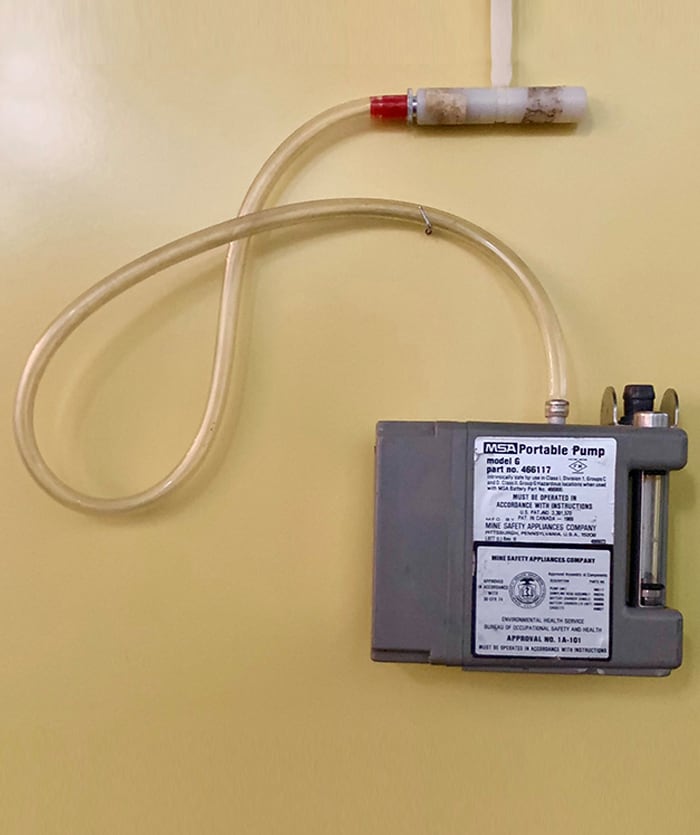

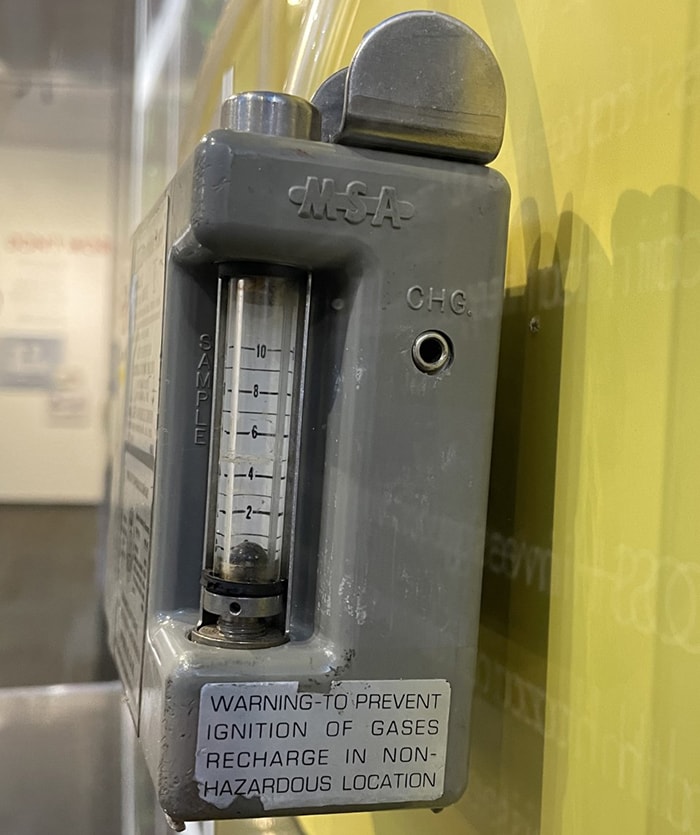

This month’s Out of the CDC Museum Collection features a revolutionary device: The MSA Portable Pump Model G, Part No. 466117. This device was developed to ensure safe, clean air in the workplace. Good air quality is essential for improving health conditions of all factory workers and laborers, especially those with respiratory diseases.

The MSA Portable Pump Model G Part No. 466117 captured air samples and is a part of the CDC Museum collection. This grey pump was worn on the worker’s waist, and its long tube was stretched out and attached to their clothing at mouth level. This technique obtained samples of the air workers were actually breathing, as opposed to an air sampler just being mounted on the wall of the factory.

Photographs of original air sampler device used by CDC’s NIOSH in 1973, MSA Portable Pump Model G Part No. 466117

This first model that factory workers could wear was used by CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) to investigate worker over-exposure to solvent vapors at the General Electric Company facility in 1973. Since then, the device has led to the development of additional air sampling devices used to collect data that better inform factory workers, labor unions, and manufacturers about air quality.