PART 1 Summaries of Notifiable Diseases in the United States, 2011

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Summary of Notifiable Diseases — United States, 2011

Please note: An erratum has been published for this article. To view the erratum, please click here.

Division of Notifiable Diseases and Healthcare Information, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, CDC

Preface

The Summary of Notifiable Diseases — United States, 2011 contains the official statistics, in tabular and graphic form, for the reported occurrence of nationally notifiable infectious diseases in the United States for 2011. Unless otherwise noted, the data are final totals for 2011 reported as of June 30, 2012. These statistics are collected and compiled from reports sent by state health departments and territories to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS), which is operated by CDC in collaboration with the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE). The Summary is available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/mmwr_nd/index.html. This site also includes Summary publications from previous years.

The Highlights section presents noteworthy epidemiologic and prevention information for 2011 for selected diseases and additional information to aid in the interpretation of surveillance and disease-trend data. Part 1 contains tables showing incidence data for the nationally notifiable infectious diseases reported during 2011.* The tables provide the number of cases reported to CDC for 2011 and the distribution of cases by month, geographic location, and patients' demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race, and ethnicity). Part 2 contains graphs and maps that depict summary data for certain notifiable infectious diseases described in tabular form in Part 1. Part 3 contains tables that list the number of cases of notifiable diseases reported to CDC since 1980. This section also includes a table enumerating deaths associated with specified notifiable diseases reported to CDC's National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) during 2003–2009. The Selected Reading section presents general and disease-specific references for notifiable infectious diseases. These references provide additional information on surveillance and epidemiologic concerns, diagnostic concerns, and disease-control activities.

Comments and suggestions from readers are welcome. To increase the usefulness of future editions, comments regarding the current report and descriptions of how information is or could be used are invited. Comments should be sent to Data Operations Team–NNDSS at NNDSSweb@cdc.gov.

* No cases of diphtheria; eastern equine encephalitis virus disease, nonneuroinvasive; poliomyelitis, paralytic; poliovirus infection, nonparalytic; rubella, congenital syndrome; severe acute respiratory syndrome–associated coronavirus disease; smallpox; vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; western equine encephalitis virus disease, neuroinvasive and non-neuroinvasive; yellow fever; and viral hemorrhagic fevers were reported in 2011. Data on hepatitis B virus, perinatal infection, and chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection (past or present) are not included because they are undergoing data quality review.

Background

The infectious diseases designated as notifiable at the national level during 2011 are listed in this section. A notifiable disease is one for which regular, frequent, and timely information regarding individual cases is considered necessary for the prevention and control of the disease. A brief history of the reporting of nationally notifiable infectious diseases in the United States is available at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/script/history.aspx. In 1961, CDC assumed responsibility for the collection and publication of data on nationally notifiable diseases. NNDSS is neither a single surveillance system nor a method of reporting. Certain NNDSS data are reported to CDC through separate surveillance information systems and through different reporting mechanisms; however, these data are aggregated and compiled for publication purposes.

Notifiable disease reporting at the local level protects the public's health by ensuring the proper identification and follow-up of cases. Public health workers ensure that persons who are already ill receive appropriate treatment; trace contacts who need vaccines, treatment, quarantine, or education; investigate and halt outbreaks; eliminate environmental hazards; and close premises where spread has occurred. Surveillance of notifiable conditions helps public health authorities to monitor the effect of notifiable conditions, measure disease trends, assess the effectiveness of control and prevention measures, identify populations or geographic areas at high risk, allocate resources appropriately, formulate prevention strategies, and develop public health policies. Monitoring surveillance data enables public health authorities to detect sudden changes in disease occurrence and distribution, identify changes in agents and host factors, and detect changes in health-care practices.

The list of nationally notifiable infectious diseases is revised periodically. A disease might be added to the list as a new pathogen emerges, or a disease might be deleted as its incidence declines. Public health officials at state health departments and CDC collaborate in determining which diseases should be nationally notifiable. CSTE, with input from CDC, makes recommendations annually for additions and deletions. Although disease reporting is mandated by legislation or regulation at the state and local levels, state reporting to CDC is voluntary. Reporting completeness of notifiable diseases is highly variable and related to the condition or disease being reported (1). The list of diseases considered notifiable varies by state and year. Current and historic national public health surveillance case definitions used for classifying and enumerating cases consistently across reporting jurisdictions are available at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/script/casedefDefault.aspx.

Infectious Diseases Designated as Notifiable at the National Level During 2011*

Anthrax

Arboviral diseases, neuroinvasive and nonneuroinvasive†

California serogroup viruses

Eastern equine encephalitis virus

Powassan virus

St. Louis encephalitis virus

West Nile virus

Western equine encephalitis virus

Babesiosis

Botulism

foodborne

infant

other (wound† and unspecified)

Brucellosis

Chancroid

Chlamydia trachomatis infection

Cholera

Coccidioidomycosis

Cryptosporidiosis†

Cyclosporiasis

Dengue virus infections

Dengue Fever

Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

Dengue Shock Syndrome

Diphtheria

Ehrlichiosis/Anaplasmosis

Ehrlichia chaffeensis

Ehrlichia ewingii

Anaplasma phagocytophilum

Undetermined

Giardiasis

Gonorrhea

Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease

Hansen disease (leprosy)

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

Hemolytic uremic syndrome, post-diarrheal

Hepatitis, viral

Hepatitis A, acute†

Hepatitis B, acute†

Hepatitis B virus, perinatal infection

Hepatitis B, chronic†

Hepatitis C, acute†

Hepatitis C, past or present†

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection diagnosis§

Influenza-associated pediatric mortality

Legionellosis

Listeriosis

Lyme disease†

Malaria

Measles

Meningococcal disease

Mumps

Novel influenza A virus infections

Pertussis

Plague

Poliomyelitis, paralytic

Poliovirus infection, nonparalytic

Psittacosis

Q fever

Acute

Chronic

Rabies

Animal

Human

Rubella

Rubella, congenital syndrome

Salmonellosis

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) disease

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC)

Shigellosis

Smallpox

Spotted fever rickettsiosis

Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome

Streptococcus Pneumoniae, invasive disease

Syphilis

Syphilis, congenital

Tetanus

Toxic-shock syndrome (other than streptococcal)†

Trichinellosis

Tuberculosis

Tularemia

Typhoid fever

Vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) infection

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) infection

Varicella (morbidity)

Varicella (mortality)

Vibriosis

Viral Hemorrhagic Fever†

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic fever virus

Ebola virus

Lassa virus

Lujo virus

Marburg virus

New World Arenaviruses (Guanarito, Machupo, Junin, and Sabia viruses)

Yellow fever

* This list reflects position statements approved in 2010 by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) for national surveillance, which were implemented in January 2011. The following changes were made to the 2011 list of nationally notifiable infectious diseases to create the 2011 list: 1) babesiosis and coccidioidomycosis were added to the list, and 2) Lujo virus was included in the category of viral hemorrhagic fever.

† 2011 reflects a modified surveillance case definition for this condition, per approved 2010 CSTE position statements.

§ AIDS has been reclassified as HIV stage III.

Data Sources

Provisional data concerning the reported occurrence of nationally notifiable infectious diseases are published weekly in MMWR. After each reporting year, staff in state health departments finalize reports of cases for that year with local or county health departments and reconcile the data with reports previously sent to CDC throughout the year. These data are compiled in final form in the Summary.

Notifiable disease reports are the authoritative and archival counts of cases. They are approved by the appropriate chief epidemiologist from each submitting state or territory before being published in the Summary. Data published in MMWR Surveillance Summaries or other surveillance reports produced by CDC programs might differ from data reported in the annual Summary because of differences in the timing of reports, the source of the data, or surveillance methodology.

Data in the Summary were derived primarily from reports transmitted to CDC from health departments in the 50 states, five territories, New York City, and the District of Columbia. Data were reported for MMWR weeks 1–52, which correspond to the period for the week ending January 8, 2011, through the week ending December 31, 2011. More information regarding infectious notifiable diseases, including case definitions, is available at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/default.aspx. Policies for reporting notifiable disease cases can vary by disease or reporting jurisdiction. The case-status categories used to determine which cases reported to NNDSS are published by disease or condition and are listed in the print criteria column of the 2011 NNDSS event code list (Exhibit).

The print criteria for NNDSS is as follows: for a case report of a nationally notifiable disease to print in the MMWR, the reporting state or territory must have designated the disease reportable in their state or territory for the year corresponding to the year of report to CDC. After the criterion is met, the disease-specific criteria listed in the Exhibit are applied. When the above-listed table indicates that all reports will be earmarked for printing, this means that cases designated with unknown or suspect case confirmation status will print just as probable and confirmed cases will print. Because CSTE position statements are not customarily finalized until July of each year, the NNDSS data for the newly added conditions are not usually available from all reporting jurisdictions until January of the year following the approval of the CSTE position statement.

Final data for certain diseases are derived from the surveillance records of the CDC programs listed below. Requests for further information regarding these data should be directed to the appropriate program.

Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

Office of Vital and Health Statistics Systems (deaths from selected notifiable diseases)

Office of Infectious Diseases

National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention

Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention (AIDS and HIV infection), Division of Viral Hepatitis, Division of STD Prevention (chancroid; Chlamydia trachomatis, genital infection; gonorrhea; and syphilis), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination (tuberculosis)

National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases

Influenza Division (influenza-associated pediatric mortality, initial detections of novel influenza A virus infections)

Division of Viral Diseases, (poliomyelitis, varicella [morbidity and mortality], and SARS-CoV)

National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases

Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (arboviral diseases)

Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases (animal rabies)

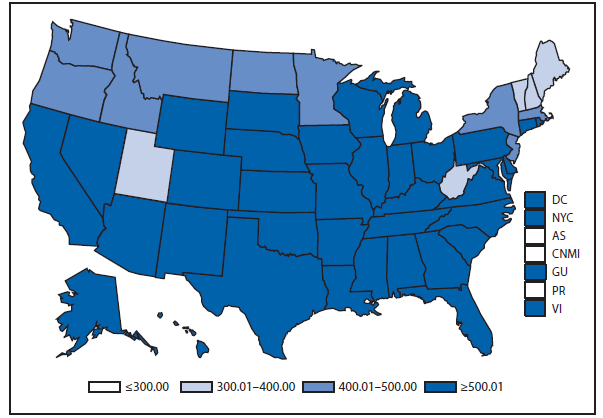

NCHS postcensal estimates of the resident population of the United States for July 1, 2010–July 1, 2011, by year, county, single-year of age (range: 0 to ≥85 years), bridged-race, (white, black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander), Hispanic origin (not Hispanic or Latino, Hispanic or Latino), and sex (Vintage 2010), prepared under a collaborative arrangement with the U.S. Census Bureau. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race/data_documentation.htm#vintage2010 as of May 31, 2012.

Population estimates for territories are 2010 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. The choice of population denominators for incidence reported in MMWR is based on 1) the availability of census population data at the time of preparation for publication and 2) the desire for consistent use of the same population data to compute incidence reported by different CDC programs. Incidence in the Summary is calculated as the number of reported cases for each disease or condition divided by either the U.S. resident population for the specified demographic population or the total U.S. resident population, multiplied by 100,000. When a nationally notifiable disease is associated with a specific age restriction, the same age restriction is applied to the population in the denominator of the incidence calculation. In addition, population data from states in which the disease or condition was not reportable or was not available were excluded from incidence calculations. Unless otherwise stated, disease totals for the United States do not include data for American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, or the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Interpreting Data

Incidence data in the Summary are presented by the date of report to CDC as determined by the MMWR week and year assigned by the state or territorial health department, except for the domestic arboviral diseases, which are presented by date of diagnosis. Data are reported by the jurisdiction of the person's "usual residence" at the time of disease onset (http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/document/03-ID-10_residency_rules.pdf). For certain nationally notifiable infectious diseases, surveillance data are reported independently to different CDC programs. For this reason, surveillance data reported by other CDC programs might vary from data reported in the Summary because of differences in 1) the date used to aggregate data (e.g., date of report or date of disease occurrence); 2) the timing of reports; 3) the source of the data; 4) surveillance case definitions; and 5) policies regarding case jurisdiction (i.e., which state should report the case to CDC).

Data reported in the Summary are useful for analyzing disease trends and determining relative disease numbers. However, reporting practices affect how these data should be interpreted. Disease reporting is likely incomplete, and completeness might vary depending on the disease and reporting state. The degree of completeness of data reporting might be influenced by the diagnostic facilities available, control measures in effect, public awareness of a specific disease, and the resources and priorities of state and local officials responsible for disease control and public health surveillance. Finally, factors such as changes in methods for public health surveillance, introduction of new diagnostic tests, or discovery of new disease entities can cause changes in disease reporting that are independent of the actual incidence of disease.

Public health surveillance data are published for selected racial/ethnic populations because these variables can be risk markers for certain notifiable diseases. Race and ethnicity data also can be used to highlight populations for focused prevention programs. However, caution must be used when drawing conclusions from reported race and ethnicity data. Different racial/ethnic populations might have different patterns of access to health care, potentially resulting in data that are not representative of actual disease incidence among specific racial/ethnic populations. Surveillance data reported to NNDSS are in either individual case-specific form or summary form (i.e., aggregated data for a group of cases). Summary data often lack demographic information (e.g., race); therefore, the demographic-specific rates presented in the Summary might be underestimated.

In addition, not all race and ethnicity data are collected or reported uniformly for all diseases, the standards for race and ethnicity have changed over time, and the transition in implementation to the newest race and ethnicity standard has taken varying amounts of time for different CDC surveillance systems. For example, in 1990, the National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance (NETSS) was established to facilitate data collection and submission of case-specific data to CDC's National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, except for selected diseases. In 1990, NETSS implemented the 1977 Office of Management and Budget (OMB) standard for race and ethnicity, in which race and ethnicity were collected in one variable. Other surveillance programs implemented two variables for collection of race and ethnicity data. The 1997 OMB race and ethnicity standard, which requires collection of multiple races per person using multiple race variables, should have been implemented by federal programs beginning January 1, 2003. In 2003, the CDC Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS programs were able to update their surveillance information systems to implement 1997 OMB standards. In 2005, the Sexually Transmitted Diseases Management Information System also was updated to implement the 1997 OMB standards. However other diseases reported to the NNDSS using NETSS were undergoing a major change in the manner in which data were collected and reported to CDC. This change is caused by the transition from NETSS to the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS), which implemented the newer 1997 OMB standard for race and ethnicity. However, the transition from NETSS to NEDSS was slower than originally expected relative to reporting data to CDC using NEDSS; thus, some data are currently reported to CDC using NETSS formats, even if the data in the reporting jurisdictions are collected using NEDSS. Until the transition to NEDSS is complete, race and ethnicity data collected or reported to NETSS using different race and ethnicity standards will need to be converted to one standard. The data are now converted to the 1977 OMB standard originally implemented in NETSS. Although the recommended standard for classifying a person's race or ethnicity is based on self-reporting, this procedure might not always be followed.

Transition in NNDSS Data Collection and Reporting

Before 1990, data were reported to CDC as cumulative counts rather than as individual case reports. In 1990, using NETSS, states began electronically capturing and reporting individual case reports to CDC without personal identifiers. In 2001, CDC launched NEDSS, now a component of the Public Health Information Network, to promote the use of data and information system standards that advance the development of efficient, integrated, and interoperable surveillance information systems at the local, state, and federal levels. One of the objectives of NEDSS is to improve the accuracy, completeness, and timeliness of disease reporting at the local, state, and national levels. CDC has developed the NEDSS Base System (NBS), a public health surveillance information system currently adopted by 18 states and the District of Columbia. A total of 28 states and New York City have a state- or vendor-developed NEDSS-compatible system.The remaining nine jurisdictions, four states and five territories, are either in the process of adopting or changing their NEDSS-compatible system or use a non-NEDSS-compatible system at the time of this publication. A major feature of all NEDSS-compatible solutions, which includes NBS, is the ability to capture data already in electronic form (e.g., electronic laboratory results, which are needed for case confirmation) rather than enter these data manually as in NETSS. In 2011, a total of 18 states and the District of Columbia used NBS to transmit nationally notifiable infectious diseases to CDC, a total of 32 states and New York City used a NEDSS-compatible based system, and the remaining state and territorial jurisdictions continued to use a non-NEDSS–compatible system. Additional information concerning NEDSS is available at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/script/nedss.aspx.

Methodology for Identifying Which Nationally Notifiable Infectious Diseases Are Reportable

States and jurisdictions are sovereign entities. Reportable conditions are determined by laws and regulations of each state and jurisdiction. It is possible that some conditions deemed nationally notifiable might not be reportable in certain states or jurisdictions. Determining which nationally notifiable infectious diseases are reportable in NNDSS reporting jurisdictions was determined by asking reporting jurisdictions to update previously analyzed results of the 2010 CSTE State Reportable Conditions Assessment (SRCA) individually, because the 2011 SRCA results were not available at the time this report was prepared. The 2010 assessment solicited information from each NNDSS reporting jurisdiction (all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, New York City, and five U.S. territories) regarding which public health conditions were reportable for >6 months in 2010 by clinicians, laboratories, hospitals, or "other" public health reporters, as mandated by law or regulation. To assist in the implementation of SRCA, staff from the NNDSS program provided technical assistance to CSTE for the 2010 SRCA.

In 2007, SRCA was established and became the first collaborative project of such technical magnitude ever conducted by CSTE and CDC. Previously, CDC and CSTE had gathered public health reporting requirements independently. The 2010 SRCA collected information regarding whether each reportable condition was 1) explicitly reportable (i.e., listed as a specific disease or as a category of diseases on reportable disease lists); 2) whether it was implicitly reportable (i.e., included in a general category of the reportable disease list, such as "rare diseases of public health importance"); or 3) not reportable. Only explicitly reportable conditions were considered reportable for the purpose of national public health surveillance and thus reflected in NNDSS. Moreover, to determine whether a condition included in SRCA was reportable in at least one public health reporter category for a specific nationally notifiable infectious disease (NNID) in a reporting jurisdiction, CDC developed and applied an algorithm to analyze the data collected in SRCA. Analyzed results of the 2010 SRCA were used to determine whether a NNID was not reportable in a reporting jurisdiction in 2010 and thus noted with an "N" indicator (for "not reportable") in the front tables of this report. Unanalyzed results from the 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010 SRCA are available using CSTE's web query tool at http://www.cste.org/group/SRCAQueryRes. Additional background information has been published previously (2).

Revised International Health Regulations

In May 2005, the World Health Assembly adopted revised International Health regulations (IHR) (3) that went into effect in the United States on July 18, 2007. This international legal instrument governs the role of the World Health Organization (WHO) and its member countries, including the United States, in identifying, responding to, and sharing information about Public Health Emergencies of International Concern (PHEIC). A PHEIC is an extraordinary event that 1) constitutes a public health risk to other countries through international spread of disease, and 2) potentially requires a coordinated international response. All WHO member states are required to notify WHO of a potential PHEIC. WHO makes the final determination about the existence of a PHEIC.

The IHR are designed to prevent and protect against the international spread of diseases while minimizing the effect on world travel and trade. Countries that have adopted these rules have a much broader responsibility to detect, respond to, and report public health emergencies that potentially require a coordinated international response in addition to taking preventive measures. The IHR will help countries work together to identify, respond to, and share information about PHEIC.

The revised IHR reflects a conceptual shift from a predefined disease list to a framework of reporting and responding to events on the basis of an assessment of public health criteria, including seriousness, unexpectedness, and international travel and trade implications. A PHEIC ia an event that falls within those criteria (further defined in a decision algorithm in Annex 2 of the revised IHR). Four conditions always constitute a PHEIC and do not require the use of the IHR decision instrument in Annex 2: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), smallpox, poliomyelitis caused by wild-type poliovirus, and human influenza caused by a new subtype. Any other event requires the use of the decision algorithm to determine if it is a potential PHEIC. Examples of events that require the use of the decision instrument include, but are not limited to, cholera, pneumonic plague, yellow fever, West Nile fever, viral hemorrhagic fevers, and meningococcal disease. Other biologic, chemical, or radiologic events might fit the decision algorithm and also must be reportable to WHO.

Health-care providers in the United States are required to report diseases, conditions, or outbreaks as determined by local, state, or territorial law and regulation, and as outlined in each state's list of reportable conditions. All health-care providers should work with their local, state, and territorial health agencies to identify and report events that might constitute a potential PHEIC occurring in their location. U.S. State and Territorial Departments of Health have agreed to report information about a potential PHEIC to the most relevant federal agency responsible for the event. In the case of human disease, the U.S. State or Territorial Departments of Health will notify CDC rapidly through existing formal and informal reporting mechanisms (4). CDC will further analyze the event based on the decision algorithm in Annex 2 of the IHR and notify the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Secretary's Operations Center (SOC), as appropriate.

DHHS has the lead role in carrying out the IHR, in cooperation with multiple federal departments and agencies. The DHHS SOC is the central body for the United States responsible for reporting potential events to WHO. The United States has 48 hours to assess the risk of the reported event. If authorities determine that a potential PHEIC exists, the WHO member country has 24 hours to report the event to WHO.

An IHR decision algorithm in Annex 2 has been developed to help countries determine whether an event should be reported. If any two of the following four questions can be answered in the affirmative, then a determination should be made that a potential PHEIC exists and WHO should be notified:

- Is the public health impact of the event serious?

- Is the event unusual or unexpected?

- Is there a significant risk of international spread?

- Is there a significant risk of international travel or trade restrictions?

Additional information concerning IHR is available at http://www.who.int/csr/ihr/en, http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/ihregulations.htm, and http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/PS/07-ID-06.pdf. At its annual meeting in June 2007, CSTE approved a position statement to support the implementation of IHR in the United States (4). CSTE also approved a position statement in support of the 2005 IHR adding initial detections of novel influenza A virus infections to the list of nationally notifiable diseases reportable to NNDSS, beginning in January 2007 (5).

- Doyle TJ, Glynn MK, Groseclose LS. Completeness of notifiable infectious disease reporting in the United States: an analytical literature review. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:866–74.

- Jajosky R, Rey A, Park M, et al. Findings from the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists' 2008 assessment of state reportable and nationally notifiable conditions in the United States and considerations for the future. Public Health Manag Pract 2011;17:255–64.

- World Health Organization. Third report of Committee A. Annex 2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241580410_eng.pdf.

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Events that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern. Position statement 07-ID-06. Available at http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/PS/07-ID-06.pdf.

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists position statement; 2007. National reporting for initial detections of novel influenza A viruses. Available at http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/PS/07-ID-01.pdf.

|

EXHIBIT. (Continued) Print criteria for conditions reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, 2011 |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Code |

Notifiable Condition |

Print Criteria*,† |

|

11062 |

Novel influenza A virus infections, initial detections of |

Cases with confirmed status and cases reported from CA with unknown status, verified to be confirmed, printed |

|

10190 |

Pertussis |

Cases with confirmed, probable, and unknown case status printed |

|

10440 |

Plague |

All reports printed |

|

10410 |

Poliomyelitis, paralytic |

Confirmed; unknown from CA that are verified as confirmed |

|

10405 |

Poliovirus infection, nonparalytic |

Confirmed; unknown from CA that are verified as confirmed |

|

10057 |

Powassan virus, neuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

10063 |

Powassan virus, nonneuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

10450 |

Psittacosis (Ornithosis) |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

10257 |

Q fever, acute |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

10258 |

Q fever, chronic |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

10340 |

Rabies, animal |

Confirmed and unknown from CA |

|

10460 |

Rabies, human |

Confirmed; unknown from CA verified as confirmed |

|

10200 |

Rubella |

Cases with confirmed and unknown case status printed |

|

10370 |

Rubella, congenital syndrome |

CSTE VPD print criteria used Cases with confirmed, probable, and unknown case status printed |

|

11000 |

Salmonellosis |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

10575 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) disease |

Confirmed and probable |

|

11563 |

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) |

All reports printed |

|

11010 |

Shigellosis |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

11800 |

Smallpox |

Cases with confirmed and probable case status printed |

|

10250 |

Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis |

Confirmed, probable, and unknown |

|

10051 |

St. Louis encephalitis virus, neuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

10064 |

St. Louis encephalitis virus, nonneuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

11700 |

Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

11723 |

Streptococcus pneumoniae, invasive disease (IPD) (all ages) |

Confirmed; unknown from CA |

|

10316 |

Syphilis, congenital |

All reports printed |

|

10313 |

Syphilis, early latent |

All reports printed |

|

10314 |

Syphilis, late latent |

All reports printed |

|

10318 |

Syphilis, late with clinical manifestations other than neurosyphilis |

All reports printed |

|

10311 |

Syphilis, primary |

All reports printed |

|

10312 |

Syphilis, secondary |

All reports printed |

|

10310 |

Syphilis, total primary and secondary |

All reports printed |

|

10315 |

Syphilis, unknown latent |

All reports printed |

|

10210 |

Tetanus |

All reports printed |

|

10520 |

Toxic-shock syndrome (staphylococcal) |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

10270 |

Trichinellosis |

Confirmed; unknown from CA |

|

10220 |

Tuberculosis |

Print criteria determined by the CDC Tuberculosis program |

|

10230 |

Tularemia |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

10240 |

Typhoid fever (caused by Salmonella typhi) |

Confirmed and probable; unknown from CA |

|

11663 |

Vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) |

Confirmed; unknown from CA verified as confirmed |

|

11665 |

Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) |

Confirmed; unknown from CA verified as confirmed |

|

10030 |

Varicella (Chickenpox) |

Cases with confirmed, probable, and unknown case status from CA printed |

|

EXHIBIT. (Continued) Print criteria for conditions reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, 2011 |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Code |

Notifiable Condition |

Print Criteria*,† |

|

11545 |

Vibriosis (non-cholera Vibrio species infections) |

Confirmed, probable, and unknown from CA |

|

11647 |

Viral hemorrhagic fever |

Confirmed; footnote to denote the specific virus reported to CDC |

|

10056 |

West Nile virus, neuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

10049 |

West Nile virus, nonneuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

10052 |

Western equine encephalitis virus, neuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

10065 |

Western equine encephalitis virus, nonneuroinvasive disease |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

10660 |

Yellow fever |

Data for publication received from ArboNET |

|

Abbreviations: ArboNET = Software for Arboviral Surveillance and Case Management; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CSTE = Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; VPD = Vaccine Preventable Disease. * An unknown case classification status is used when a reporting jurisdiction sends aggregate counts of cases or when the surveillance information system of a reporting jurisdiction does not capture case classification data. In both situations, cases are verified to meet the case classification (e.g., confirmed, probable, and suspected) specified in the print criteria. † Print criteria for the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS): for a case report of a nationally notifiable disease to print in the MMWR, the reporting state or territory must have designated the disease reportable in their state or territory for the year corresponding to the year of report to CDC. After this criterion is met, the disease-specific criteria listed in the Exhibit are applied. When the above-listed table indicates that all reports will be earmarked for printing, this means that cases designated with unknown or suspect case confirmation status will print just as probable and confirmed cases will print. Because CSTE position statements customarily are not finalized until July of each year, the NNDSS data for the newly added conditions usually are not available from all reporting jurisdictions until January of the year following the approval of the CSTE position statement. |

||

Highlights for 2011

Below are summary highlights for certain national notifiable diseases. Highlights are intended to assist in the interpretation of major occurrences that affect disease incidence or surveillance trends (e.g., outbreaks, vaccine licensure, or policy changes).

Anthrax

In 2011, public health authorities in Minnesota reported a confirmed case of naturally occurring inhalation anthrax was reported by Minnesota, in a Florida resident who became ill while vacationing in Minnesota and four other northern midwestern states. The patient was hospitalized and was discharged home after appropriate treatment (1). The incident resulted in a joint investigation involving law enforcement officials, state public and animal health agencies, the National Animal Health Laboratory Network, Laboratory Response Network, CDC, and other federal agencies. The investigation revealed that during the 3 weeks of travel before disease onset the patient collected rocks and handled antlers and other animal items, and had been exposed to dust clouds while driving through areas inhabited by herds of animals. No Bacillus anthracis was detected through testing of associated animal products or environmental samples, and public health officials were unable to identify the source of the exposure. Enhanced surveillance was performed in states where the person had traveled, and no other humans or animals infected with the case strain were identified; this case is considered an isolated naturally occurring case. The incidence of anthrax in the United States and U.S. territories remains low, with two or fewer naturally occurring cases reported per year for the past 30 years.

- Minnesota Department of Health. Health officials investigate case of inhalational anthrax from suspected natural environmental exposure. Available at http://www.health.state.mn.us/news/pressrel/2011/anthrax080911.html.

Domestic Arboviral, Neuroinvasive and Nonneuroinvasive

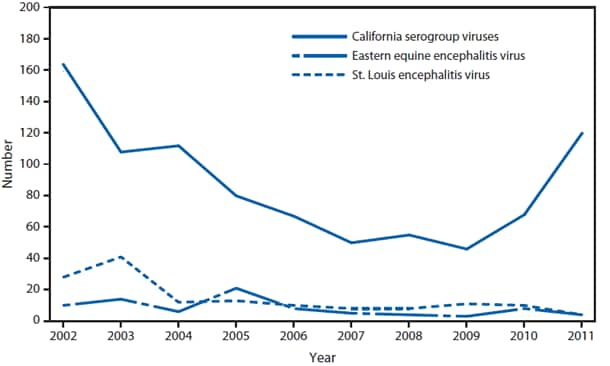

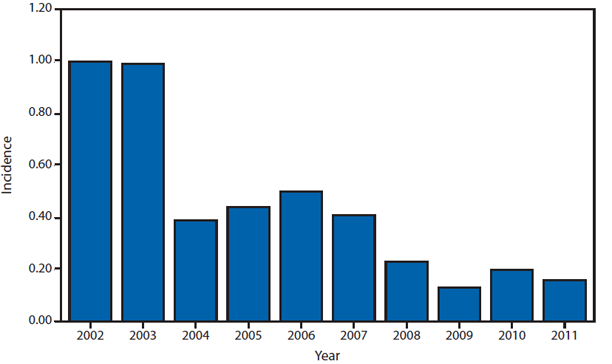

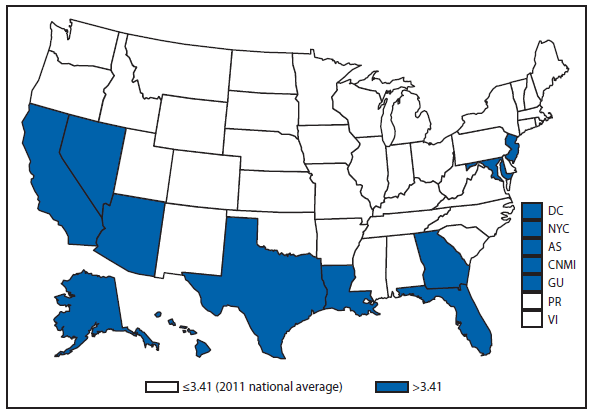

During 2011, West Nile virus (WNV) disease cases were reported from 43 states and the District of Columbia. The reported incidence of neuroinvasive disease was 0.16 cases per 100,000 population. Despite the decline in neuroinvasive disease incidence compared with previous years, the overall morbidity caused by WNV continues to be substantial. Based on previous studies, for every reported case of neuroinvasive disease, approximately 140–350 human WNV infections occur, with approximately 80% of infected persons remaining asymptomatic and 20% developing nonneuroinvasive disease (1–3). Using the 486 reported neuroinvasive disease cases, an estimated 13,600–34,000 cases of nonneuroinvasive disease might have occurred in 2011. However, only 226 nonneuroinvasive disease cases were diagnosed and reported; 1%–2% of the cases estimated to have occurred. Evidence of WNV human disease was detected in all geographic regions of the United States. The states with the highest incidence of neuroinvasive disease were the District of Columbia (1.62 per 100,000 population), Mississippi (1.04), Nebraska (0.76), and Arizona (0.76). Among the neuroinvasive disease cases, 250 (51%) cases were reported from five states: California (110 cases), Arizona (49), Michigan (32), Mississippi (31), and New York (28). California reported 23% of all WNV neuroinvasive disease cases in 2011 (4).

Among the other domestic arboviral diseases in the United States, La Crosse virus remained the most common cause of neuroinvasive disease in children. Eastern equine encephalitis virus disease, although rare, remained the most severe arboviral disease, resulting in three deaths among four patients. More Powassan virus disease cases were reported in 2011 than in any previous year, and included the first case ever reported from Pennsylvania. Wisconsin reported its first Eastern equine encephalitis disease case since 1984.

- Mostashari F, Bunning ML, Kitsutani PT, et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: results of a household-based seroepidemiological survey. Lancet 2001;358:261–4.

- Busch MP, Wright DJ, Custer B, et al. West Nile virus infections projected from blood donor screening data, United States, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:395–402.

- Carson PJ, Borchardt SM, Custer B, et al. Neuroinvasive disease and West Nile virus infection, North Dakota, USA, 1999–2008. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:684–6.

- CDC. West Nile virus disease and other arboviral diseases—United States, 2011. MMWR 2012;61:510–4.

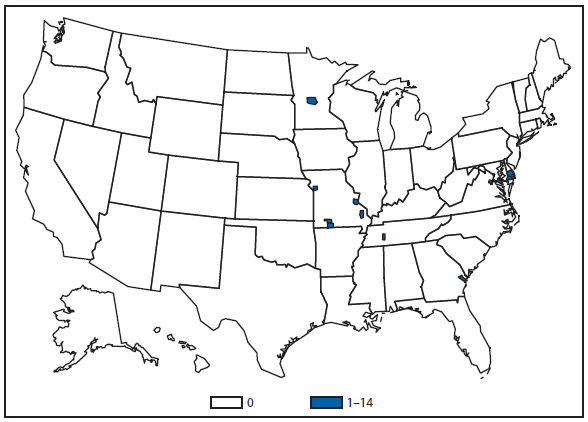

Babesiosis

Babesiosis, a tickborne parasitic disease, became a nationally notifiable condition in 2011. Babesiosis is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Babesia that infect red blood cells. Babesia infection can range from asymptomatic to life threatening. Clinical manifestations can include fever, chills, other nonspecific influenza-like symptoms, and hemolytic anemia. Babesia parasites usually are tickborne, but they also are transmissible via blood transfusion or congenitally (1). In recent years, reports of tickborne and transfusion-associated cases have increased in number and geographic distribution (1).

In 2011, public health authorities in seven states (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) reported the majority (97%) of babesiosis cases, with 1,092 of 1,128 cases. The median age of patients was 62 years (range: age <1–98 years); 62% (n = 700) were male, 34% (n = 386) were female, and the sex was unknown for 4% (n = 42) of patients. Among the patients for whom data were available, 82% (717 of 879) had symptom onset dates during June–August (2).

- Herwaldt BL, Linden JV, Bosserman E, et al. Transfusion-associated babesiosis in the United States: a description of cases. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:509–19.

- CDC. Babesiosis surveillance—18 states, 2011. MMWR 2012;61:505–9.

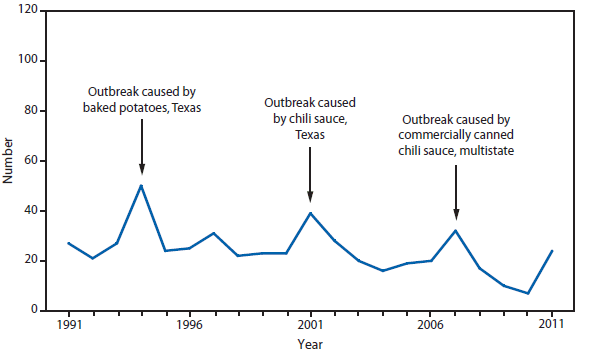

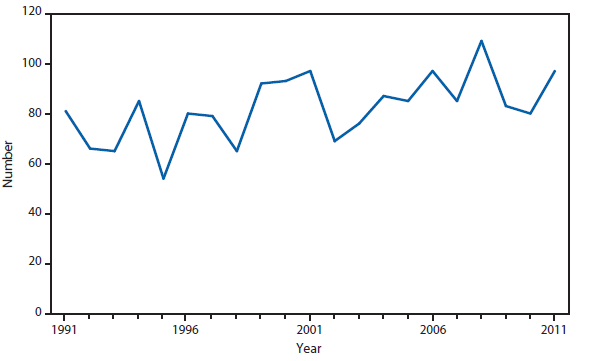

Botulism

Botulism is a severe paralytic illness caused by toxins produced by Clostridium botulinum. Exposure to the toxin can occur by ingestion (foodborne botulism), by in situ production from C. botulinum colonization of a wound (wound botulism) or the gastrointestinal tract (infant botulism and adult intestinal colonization botulism), or overdose of botulinum toxin used for cosmetic or therapeutic purposes (1). Infant botulism continues to be the most frequently observed transmission category. During 2011, eight persons located in a prison acquired foodborne botulism after consuming pruno, an illicitly brewed alcoholic beverage.

All states maintain 24-hour telephone services for reporting of botulism and other public health emergencies. Health-care providers should report suspected botulism cases immediately to their state health departments. CDC maintains intensive surveillance for cases of botulism in the United States and provides consultation to clinicians and antitoxin for suspected cases. State health departments can reach the CDC botulism duty officer on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, via the CDC Emergency Operations Center (telephone: 770-488-7100).

- Sobel J. Botulism. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1167–73.

Brucellosis

Brucellosis is an infectious disease that can be acquired by persons who come into contact with infected animals or animal products contaminated with the bacteria. The number of brucellosis cases reported in 2011 decreased by 31%, from 115 cases in 2010 to 79 cases in 2011. The five states (California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, and Texas) reported 45 cases, accounting for approximately 57% of all cases. No cases were reported from any U.S. territories.

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services approved a revised brucellosis case report form. Health departments and providers are strongly encouraged to use the approved form to report brucellosis cases to CDC's Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch. This mechanism will ensure collection of standardized data needed to assess risk factors and trends associated with brucellosis better so that targeted preventive strategies can be implemented. A fillable PDF version of the form is available at http://www.cdc.gov/nczved/divisions/dfbmd/diseases/brucellosis/case-report-form.pdf. The form also can be requested via e-mail (bspb@cdc.gov) or by telephone (404-639-1711). Patient identifiers such as full name, address, phone number, hospital name, and chart number should not be included in forms sent to CDC. Instructions for completion and submission of the form are included in pages 1 and 2 of the form.

Chlamydia

In 2011, approximately 1.4 million cases of Chlamydia trachomatis infections were reported, the largest number of cases ever reported to CDC for any condition (1). This case count corresponds to a rate of 457.6 cases per 100,000 population, an increase of 8% compared with the rate in 2010. Rates of reported chlamydial infections among women have been increasing annually since the late 1980s, when public programs for screening and treatment of women were established to avert pelvic inflammatory disease and related complications. The continued increase in chlamydia case reports in 2011 likely represents a continued increase in screening for this usually asymptomatic infection, expanded use of more sensitive tests, and more complete national reporting; however, it also might reflect an increase in morbidity.

- CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012.

Cholera

Cholera continues to be rare in the United States and is acquired most often during travel in countries where toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139 is circulating (1). Since epidemic cholera emerged in Haiti in October 2010, cases have continued to be reported in the United States among travelers who have arrived recently from Hispaniola. Of the 42 cholera infections reported in the United States in 2011, a total of 39 were travel associated; 22 patients had arrived recently from Haiti, 11 from the Dominican Republic, and six from other cholera-affected countries. Until the cholera epidemic in Hispaniola wanes, associated cases are expected to continue to occur in the United States (2). Cholera remains a global threat to health, particularly in areas with poor access to improved water and sanitation, such as Haiti and sub-Saharan Africa (3,4).

- Steinberg EB, Greene KD, Bopp CA, et al. Cholera in the United States, 1995–2000: trends at the end of the Twentieth Century. J Infect Dis 2001;184:799–802.

- Newton AE, Heiman KE, Schmitz A, et al. Cholera in United States associated with epidemic in Hispaniola. Emerg Infect Dis 2011;17:2166–8.

- Tappero J, Tauxe RV. Lessons learned during public health response to cholera epidemic in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Emerg Infect Dis 2011;17:2087–93.

- Mintz ED, Guerrant RL. A lion in our village—the unconscionable tragedy of cholera in Africa. New Engl J Med 2009;360:1061–3.

Coccidioidomycosis

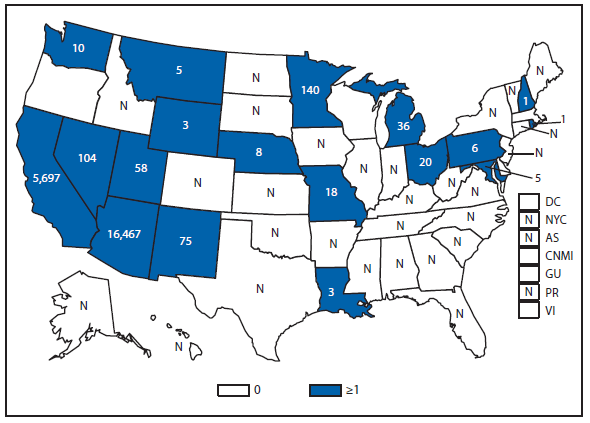

Coccidioidomycosis is a fungal infection caused by inhalation of airborne Coccidioides spp. spores that are present in the arid soil of the southwestern United States, California, and parts of Central and South America. The incidence of coccidioidomycosis increased in 2011, for the second consecutive year in California, Arizona, and other states. Coccidioidomycosis was not a nationally notifiable condition during 2010, although many states reported cases. In 2011, coccidioidomycosis incidence increased among all age groups, although rates remain highest among persons aged ≥60 years. Since 2009, the majority of cases have occurred among women in Arizona, whereas the majority of cases have occurred among men elsewhere in the United States. The 16,467 cases reported from Arizona and 5,697 cases from California during 2011 represent a 61% and 129% increase, respectively, compared with 2009. Coccidioidomycosis is currently the second most commonly reported condition in Arizona, and the fourth in California.

The morbidity of this disease in Arizona is considerable (1). Enhanced surveillance conducted during 2007–2008 demonstrated a self-reported median duration of illness of 42 days among persons who had recovered at the time of the interview and 157 days among those who had not; a total of 200 (41%) patients were hospitalized for coccidioidomycosis; a total of 67 (74%) employed persons and 37 (59%) students were unable to attend work or school (1).

Whether the recent increase is related to changes in surveillance methodology is not known. In 2009, one of the major commercial laboratories in Arizona changed its reporting practices to conform to the CSTE laboratory case definition, which was revised in 2007 to include cases with a single positive enzyme immunoassay result (2). The majority of laboratories in endemic areas perform testing using an enzyme immunoassay, the specificity of which is controversial (3).

Physicians, particularly in areas where the disease is endemic, should continue to maintain a high suspicion for acute coccidioidomycosis, especially among patients with an influenza-like illness or pneumonia who live in or have visited areas in which the disease is endemic.

- Tsang CA, Anderson SM, Imholte SB, et al. Enhanced surveillance of coccidioidomycosis, Arizona, USA, 2007–2008. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;11:1738–44.

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Revision of the surveillance case definition for coccidioidomycosis. Position statement 07-ID-13. Atlanta, GA: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; 2007. Available at http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/PS/07-ID-13.pdf.

- Kuberski T, Herrig J, Pappagianis D. False-positive IgM serology in coccidioidomycosis. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:2047–9.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis is a nationally notifiable gastrointestinal illness caused by chlorine-tolerant protozoa of the genus Cryptosporidium. Cryptosporidium is transmitted by the fecal-oral route with the ingestion of Cryptosporidium oocysts through the consumption of fecally contaminated food or water or through direct person-to-person or animal-to-person contact.

Although cryptosporidiosis affects persons in all age groups, cases are reported most frequently in children (1). A substantial increase in transmission of Cryptosporidium in children occurs during summer through early fall, coinciding with increased use of recreational water, which is a known risk factor for cryptosporidiosis. Cryptosporidium has emerged as the leading cause of reported recreational water-associated outbreaks (2). Transmission through recreational water is facilitated by the substantial number of Cryptosporidium oocysts that can be shed by a single person, the extended time that oocysts can be shed (3), the low infectious dose (4), and the extreme tolerance of Cryptosporidium oocysts to chlorine (5).

To reduce the number of cryptosporidiosis cases associated with recreational water, enhanced public health prevention measures are needed. In the United States, pool codes are reviewed and approved by state or local public health officials; no federal agency regulates the design, construction, and operation of treated recreational water venues. This lack of uniform national standards has been identified as a barrier to the prevention and control of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water. To provide support to state and local health departments, CDC is sponsoring development of the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC) (http://www.cdc.gov/mahc). MAHC is a collaborative effort between local, state, and federal public health agencies and the aquatics sector to develop a data-driven, knowledge-based resource for state and local jurisdictions reviewing and updating their existing pool codes to optimally prevent and control recreational water-associated illness, including cryptosporidiosis.

- CDC. Cryptosporidiosis surveillance—United States, 2009–2010. MMWR 2012;61(No. SS-5):1–12.

- CDC. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks and other health events associated with recreational water—United States, 2007–2008. MMWR 2011;60(No. SS-12):1–32.

- Chappell CL, Okhuysen PC, Sterling CR, DuPont HL. Cryptosporidium parvum: intensity of infection and oocyst excretion patterns in healthy volunteers. J Infect Dis 1996;173:232–6.

- Chappell CL, Okhuysen PC, Langer-Curry R, et al. Cryptosporidium hominis: experimental challenge of healthy adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006;75:851–7.

- Shields JM, Hill VR, Arrowood MJ, Beach MJ. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum under chlorinated recreational water conditions. J Water Health 2008;6:513–20.

Dengue

With more than one third of the world's population living in areas at risk for transmission, dengue infection is a leading cause of illness and death in the tropics and subtropics. As many as 100 million persons are infected yearly. Dengue is caused by any one of four related viruses transmitted by mosquitoes.

Dengue in the United States occurs among persons living in subtropical and tropical areas where the disease is endemic, among U.S. travelers returning from endemic areas worldwide, and occasionally among persons living in U.S. areas that are not endemic for dengue but that are experiencing an outbreak. In 2011, a total of 1,541 dengue cases were reported to the national arbovirus surveillance network (ArboNET) from the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and 254 cases were reported from 31 U.S. states. This represents a decrease in reported cases from Puerto Rico, and the U.S. states in 2010 (1). The overall decrease in 2011 in reported dengue cases both from U.S. areas that are and are not endemic for dengue was considered to be because of the cyclical nature of this disease worldwide and the decrease in global dengue cases (2–5).

Dengue is endemic in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the U.S.-affiliated Pacific Islands (USAPI); (i.e., the U.S.-territories of Guam and American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Republic of Palau, the Republic of the Marshall Islands [RMI], and the Federated States of Micronesia [FSM]). Although dengue is a notifiable disease in most U.S. territories and USAPIs, only Puerto Rico reports dengue cases to ArboNET (6). Puerto Rico did not experience an outbreak year in 2011; however, dengue outbreaks occurred in RMI and FSM. During September–December 2011, a total of 1,408 suspected cases were reported to the RMI Ministry of Health, and 1,017 suspected cases were reported from Yap state to the FSM Department of Health Services. Dengue virus (DENV)-2 and DENV-4 transmission was confirmed during the Yap and RMI outbreaks, respectively. Both outbreaks continued for several months into 2012.

Travel-associated dengue is the leading source of dengue in the U.S. areas that are not endemic for the disease, with 243 cases reported in 2011. Travel-associated dengue cases from residents of the U.S. areas that are not endemic resulted from travel to the following 42 foreign countries or U.S. territories: Puerto Rico (31), Bahamas (27), India (27), Bangladesh (16), Philippines (16), Haiti (14), Dominican Republic (10), Brazil (eight), Cuba (seven), Trinidad (seven), Costa Rica (five), and <5 cases from the Antilles, Aruba, Bermuda, Bolivia, Colombia, Curacao, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ghana, Granada, Guatemala, Guyana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Laos, Malaysia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Saint Lucia, Sudan, Thailand, Turks and Caicos, U.S. Virgin Islands, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

Although dengue is not endemic in the 50 U.S. states, an outbreak and locally acquired dengue cases were reported in Hawaii and Florida, respectively, in 2011. During February–March 2011, the Hawaii Department of Health (HI-DOH) detected laboratory-confirmed cases of dengue in five residents of Pearl City on the island of O'ahu. The first case was laboratory-confirmed in an O'ahu resident who travelled to Wisconsin in late February. After being notified by the Wisconsin Department of Health, the HI-DOH conducted case finding activities, which included a serosurvey in the index case household and neighborhood. After exhibiting dengue-like symptoms in late February, two laboratory-confirmed cases were found among the index patient's family members, and one laboratory-confirmed case was found in the neighboring household. None of these persons had travelled outside of the United States in the 2 weeks before illness onset and the virus DENV-1 was identified in two of these patients. The investigation also revealed that the likely source of virus transmission was an unrelated Pearl City resident who developed an acute febrile illness soon after returning in early February from a trip to the Philippines. In 2011, the Florida Department of Health reported cases occurring in seven persons with locally acquired dengue who had no reported travel outside of the United States in the 2 weeks before illness onset. The patients resided in Hillsborough (one patient), Martin (one), Miami-Dade (three), and Palm Beach (two) counties.

- CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2010. MMWR 2012;59(No. SS-3):1–111.

- World Health Organization (WHO)—Western Pacific Region Office (WPRO). WPRO Dengue situation update; 2012. Available at http://www.wpro.who.int/emerging_diseases/12_Jan2012DengueBiWeekly.pdf.

- World Health Organization—Pan American Health Organization. Number of reported cases of dengue and severe dengue in the Americas by country: Figures for 2010; 2010. Available at http://new.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/dengue_cases_2010_december_10_2%20.pdf.

- World Health Organization—Pan American Health Organizatin. Number of reported cases of dengue and dengue severe in the Americas by country: Figures for 2011; 2011. Available at http://new.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2011/dengue_cases_2011_January_21_EW_3.pdf.

- Dash AP. From the editor's desk. Dengue Bulletin 2011;35:i–i.

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. State reportable conditions query results, 2012. Available at http://www.cste.org/group/SRCAQueryRes.

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis

Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are rickettsial tickborne diseases. The number of reported cases of anaplasmosis increased by approximately 50%, from 1,761 cases in 2010 to 2,575 cases in 2011, the largest reported incidence since anaplasmosis became notifiable in 1998. The number of reported cases of ehrlichiosis increased by 15%, from 740 cases in 2010 to 850 cases in 2011. A case of Ehrlichia ewingii was reported for the first time from Georgia, Maryland, and Virginia. Reports of undetermined ehrlichiosis or anaplasmosis increased by approximately 40% from 104 cases in 2010 to 148 cases in 2011. The overall increase in reported incidence of all four categories of ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis from 2010 to 2011 might indicate an increase in tick populations, expansion of tick vector range, and an increase in the use of diagnostic assays.

Giardiasis

Giardia is transmitted through the fecal-oral route with the ingestion of Giardia cysts through the consumption of fecally contaminated water or through person-to-person (or, to a lesser extent, animal-to-person) transmission. The disease normally is characterized by diarrhea, abdominal cramps, bloating, weight losss, and malabsorption.

Although giardiasis is the most common enteric parasitic infection in the United States and no declines in incidence have occurred in recent years, knowledge of its epidemiology remains incomplete. Giardiasis symptomatology is variable; infected persons can shed Giardia for several weeks, and recent studies indicate a potential for chronic sequelae from giardiasis (1,2). New epidemiologic studies are needed to identify effective public health prevention measures.

Most data on giardiasis transmission come from outbreak investigations; however, the overwhelming majority of reported giardiasis cases are not linked to known outbreaks. During 2009–2010, <1% of reported giardiasis cases were associated with outbreaks (3). The relative contributions of person-to-person, animal-to-person, foodborne, and waterborne transmission to sporadic human giardiasis in the United States are not well understood.

Until recently, no reliable serologic assays for Giardia have been available, and no population studies of Giardia seroprevalence have been conducted. With recent laboratory advances (4), such studies might now be feasible and would contribute substantially to understanding the prevalence of giardiasis in the United States. Enhanced genotyping methods would increase knowledge of the molecular epidemiology of Giardia, including elucidating species-specific subassemblages (5). These tools, combined with traditional epidemiology and surveillance, would improve understanding of giardiasis risk factors, enable researchers to identify outbreaks by linking cases currently classified as sporadic infections, and provide risk factor information needed to inform prevention strategies.

- Cantey PT, Roy S, Lee B, et al. Study of nonoutbreak giardiasis: novel findings and implications for research. Am J Med 2011;124:1175.e1–8.

- Wensaas KA, Langeland N, Hanevik K, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 3 years after acute giardiasis: historic cohort study. Gut 2012;61:214–9.

- CDC. Giardiasis surveillance—United States, 2009–2010. MMWR 2012;61 (No. SS-5):13–23.

- Priest JW, Moss DM, Visvesvara GS, et al. Multiplex assay detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies that recognize Giardia intestinalis and Cryptosporidium parvum antigens. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2010;17:1695–707.

- Feng Y, Xiao L. Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:110–40.

Gonorrhea

After a 79% decline in the rate of reported gonorrhea during 1975–2009, and after reaching the lowest gonorrhea rate recorded in 2009, the national gonorrhea rate increased in 2011 for the second consecutive year. During 2009–2011, the national rate of gonorrheal infection increased by 6% to 104 cases per 100,000 population. In 2011, the rate increased among men and women, among all racial/ethnic groups, and in all four regions of the United States (West, Midwest, Northeast, and South). As in previous years, the highest rates were observed among persons aged 15–24 years, among blacks, and in the South. In 2011, the gonorrhea rate among blacks was 17 times higher than the rate among whites (427 cases in blacks per 100,000 population compared with 25 cases in whites per 100,000 population) (1).

Treatment for gonorrhea is complicated by antimicrobial resistance. Most recently, declining susceptibility to cefixime resulted in a change in the CDC treatment guidelines; dual therapy with ceftriaxone and either azithromycin or doxycycline is now the only CDC-recommended treatment regimen for gonorrhea (2). In 2011, no isolates with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone were identified in CDC's sentinel surveillance system, the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP); the percentage of isolates with elevated cefixime minimum inhibitory concentrations remain unchanged. Three isolates with decreased susceptibility to cefixime were identified within GISP from three different regions of the United States in 2011 (1).

- CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012.

- CDC. Update to CDC's sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. MMWR 2012;61:590–4.

Hansen Disease (Leprosy)

The number of reported cases decreased by 16%, from 98 cases in 2010 to 82 cases in 2011. The geographic distribution of cases reported in 2011 was the same as that reported in 2010, with Florida, Texas, California, and Hawaii reporting 61 cases and accounting for the majority (approximately 75%) of 82 reported cases. No cases were reported from any U.S. territories.

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) is a severe, sometimes fatal, respiratory disease in humans caused by infection with a hantavirus. Anyone who comes into contact with rodents that carry hantavirus is at risk for HPS. Rodent infestation in and around the home remains the primary risk for hantavirus exposure.

In 2011, HPS was confirmed in a rural Maine resident. This was the first person to have developed HPS from exposure to mice in Maine. Also in 2011, a fatal case of HPS occurred in a Long Island, New York, resident. This was the second case of HPS in a New York resident since 1995, and the fourth case in a person potentially exposed to rodents in the state. Although 517 (>95%) of 538 HPS cases have occurred west of the Mississippi river (1), the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus, reservoir for Sin Nombre virus) and the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus, reservoir for the New York virus) are distributed widely throughout North America, and the potential for hantavirus infection is present wherever persons come into contact with an infected rodent (2).

- Knust B, MacNeil A, Rollin PE. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome clinical findings: evaluating a surveillance case definition. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2012;12:393–9.

- Mills JN, Amman BR, Glass GE. Ecology of hantaviruses and their hosts in North America. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2009;10:563–74.

Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality

In June 2004, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists added influenza-associated pediatric mortality (i.e., among persons aged <18 years) to the list of conditions reportable to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Cumulative year-to-date incidence data are published each week in MMWR Table 1 for low-incidence nationally notifiable diseases. MMWR counts of deaths are by date of report in a calendar year and not by date of occurrence. A total of 118 influenza-associated pediatric deaths reported to CDC during 2011. Although all deaths occurred during the 2010–2011 influenza season, 10 of these deaths occurred in 2010, and were reported several months later in 2011. A total of 108 deaths occurred in 2011. This compares with a mean of 68 deaths (range: 43–90) per year that have been reported for seasonal influenza during 2005–2010. A total of 358 deaths were reported from April 15, 2009 to September 30, 2010, coinciding with the 2009 pandemic virus influenza A (H1N1)(pH1N1).

Of the 118 influenza-associated pediatric deaths reported to CDC during 2011, a total of 117 occurred between November 2010 and April 2011, and one occurred during August 2011. Seventy-three (62%) deaths were associated with influenza A viruses and 45 (38%) with influenza B viruses. Among the 73 influenza A virus-associated deaths, a subtype was determined for 54 (74%); 31 were influenza A (H1N1) (pH1N1) and 23 were A (H3N2) viruses.

In 2011, the median age at the time of death was 5.7 years (range: 25 days–17.9 years). This is similar to that observed (4–7.5 years) before the 2009 A (H1N1) pandemic for the years 2005–2008 and January–April 2009 but lower than that seen when pH1N1 viruses circulated widely during May–December 2009 (9.3 years) and 2010 (8.2 years). Sixteen children (14%) were aged <6 months; 18 (15%) were aged 6–23 months; 21 (18%) were aged 24–59 months; 17 (14%) were aged 5–8 years; 17 (14%) were aged 9–12 years; and the remaining 29 (25%) were aged 13–17 years. The overall influenza-associated death rate for children aged <18 years for 2011 was 0.16 per 100,000 population. The rates by age group were 0.63 per 100,000 population for children aged <1 year, 0.19 for children ≥1 year and <5 years, and 0.12 for children ≥5 and <18 years.

Information on the location of death was available for 117 of 118 children. Seventy-three children (62%) died after being admitted to the hospital (63 were admitted to an intensive care unit); 21 (18%) died in the emergency room; and 23 (20%) died outside the hospital. Information on underlying or chronic medical condition was reported for 116 (98%) children: 59 (51%) children had one or more underlying or chronic medical conditions, placing them at increased risk for influenza-associated complications (1). The most common group of underlying conditions were neurologic (e.g., moderate to severe developmental delay, seizure disorder, mitochondrial disorder, cerebral palsy, a neuromuscular disorder, or other neurological condition). These neurologic conditions were reported for 34 of 116 children for whom previous health status was known and 18 of 116 children were reported to have had a chronic pulmonary condition (e.g., asthma, cystic fibrosis, or other chronic pulmonary disease). Of 60 children who had specimens collected for bacterial culture from normally sterile sites, 23 (38%) had positive cultures. Staphylococcus aureus was detected in seven of 23 (30%) of the positive cultures; five were methicillin-resistant and two were methicillin-sensitive. Five cultures (16%) were positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae and four (20%) were positive for Group A Streptococcus. Other streptococcus species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter cloacae, were identified less frequently. Of the 72 fatal cases among children aged ≥6 months for whom seasonal vaccination status was known, 19 (26%) were vaccinated against influenza as recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for 2011(2). Continued surveillance of influenza-associated mortality is important to monitor both the effects of seasonal and novel influenza and the impact of interventions in children.

- CDC. Post-censal estimates of the resident population of the United States for July 1, 2010–July 1, 2011, by year, county, single year of age (0, 1, 12...85 years and over), bridged race, Hispanic origin, sex. Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, 2011. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race/data_documentation.htm#vintage2011.

- CDC. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) 2011. MMWR 2011;60:1128–32.

Listeriosis

Listeria monocytogenes infection (listeriosis) is rare but causes severe invasive disease (e.g., bacteremia, meningitis, and fetal death). Listeriosis has been nationally notifiable since 2000. Listeriosis is acquired predominately through contaminated food and occurs most frequently among pregnant women and their newborns, older adults, and persons with certain immunocompromising conditions. Pregnancy-associated listeriosis is usually a mild illness but can be associated with fetal death and severe neonatal disease.

In 2011, the incidence of reported listeriosis in the United States was 0.28 infections per 100,000 population. Progress toward the Healthy People 2020 (objective no. FS-1.3) of 0.20 infections per 100,000 population (1) is measured through the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), which conducts active surveillance for listeriosis in 10 U.S. states. FoodNet reported a preliminary annual incidence of Listeria monocytogenes in 2011 of 0.24 infections per 100,000 population, similar to the rate reported to NNDSS (2).

The Listeria Initiative is an enhanced surveillance system designed to aid public health authorities in the rapid investigation of listeriosis outbreaks by combining molecular subtyping results with epidemiologic data collected by state and local health departments (3). As part of the Listeria Initiative, CDC recommends that all clinical isolates of L. monocytogenes be forwarded routinely to a public health laboratory for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) subtyping, and submission of these PFGE patterns to PulseNet, the National Molecular Subtyping Network for Foodborne Disease Surveillance (4). In addition, communicable disease programs are asked to interview all listeriosis patients promptly using the standard Listeria Initiative case form, available at in English and Spanish at http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/surveillance.html.

The Listeria Initiative has allowed for timely identification and removal of contaminated food during outbreaks, including a large outbreak in 2011 linked to whole cantaloupes from a single farm (5) that resulted in 147 illnesses, 143 hospitalizations, 33 deaths, and one miscarriage (6). A second outbreak of listeriosis in 2011 was linked to ackawi and chive cheeses made from pasteurized milk; these cheeses were produced by a single manufacturer. In addition, illnesses associated with consumption of blue cheese made from unpasteurized milk were investigated (7).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 objectives. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=14.

- CDC. Foodborne diseases active surveillance network. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/foodnet/data/trends/tables/table2a-b.html#table-2b.

- CDC. The listeria initiative surveillance overview. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/pdf/ListeriaInitiativeOverview_508.pdf.

- CDC. PulseNet. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet.

- CDC. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis associated with Jensen Farms cantaloupe—United States, August–September, 2011. MMWR 2011;60:1357–8.

- CDC. Multi-state outbreak of listeriosis linked to whole cantaloupe in Jenson Farms, Colorado. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/cantaloupes-jensen-farms/082712/index.html.

- CDC. National listeria surveillance annual summary, 2011. Atlanta, Georgia. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2013.

Lyme disease

National surveillance for Lyme disease was implemented in the United States in 1991 using a case definition based on clinical and laboratory findings. CSTE revised the case definition, effective 2008, to standardize laboratory criteria for confirmation and allow reporting of "probable" cases.

The number of confirmed and probable Lyme disease cases reported to CDC increased by 2,939 (9.7%) in 2011 over 2010. Nevertheless, the total number of reported cases remained substantially lower than in either 2008 or 2009. Unlike 2010, when reported cases decreased in nearly all Northeastern and mid-Atlantic states, no consistent regional trend was apparent in 2011.

Measles

The elimination of endemic measles has been achieved in the United States (1); however, measles continues to be imported, resulting in substantial morbidity and expenditure of local, state, and federal public health resources (2,3). Although measles incidence in the United States remains low, the number of cases reported during 2011 was the highest since 1996.

A total of 191 cases accounted for the majority (87%) of persons with measles, which were unvaccinated or had unknown vaccination status; an estimated 68 (36%) were known to claim vaccine exemption based on personal, religious, or philosophical beliefs (PBEs). A total of 196 cases accounted for the majority (89%) of cases in 2011, which were import-associated. The World Health Organization, European Region, where approximately 30,000 cases occurred in 2011, accounted for the majority of imported cases (41%) among U.S. residents who acquired measles while traveling. Imported genotypes were identified in all 16 outbreaks, with 12 (75%) of the outbreaks being caused by D4 genotype virus, known to be circulating in Europe.

Seven outbreaks occurred after unvaccinated U.S. residents acquired infection abroad with onset of symptoms after returning to the United States. These outbreaks (range: 3–21 cases) accounted for 58 cases. A total of 38 (65%) persons claimed PBEs, seven (12%) were infants aged <12 months; for one child aged 12 months, measles vaccination had been delayed intentionally by parents until the child was older.

Cases in U.S. residents who were unvaccinated or who had unknown vaccine status, who had no medical contraindication to vaccination, and who were either born after 1957 or were aged ≥12 months (without prior documentation of presumptive evidence of immunity to measles), or were aged 6–11 months, with recent history of international travel, are considered vaccine-preventable. During 2011, a total of 48 of 57 imported cases occurred among unvaccinated U.S. residents who were vaccine-eligible: nine traveler cases occurred in infants aged 6–11 months; nine in infants aged 12–15 months; five in children aged 16 months–4 years; seven in persons aged 5–19 years; and 18 in persons aged 20–53 years. Among persons aged 20–53 years (median: 28 years), 44% held PBEs.

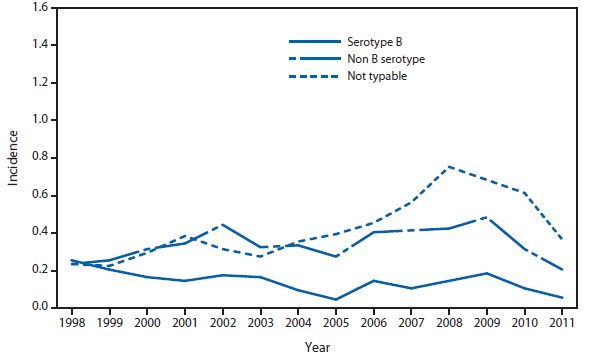

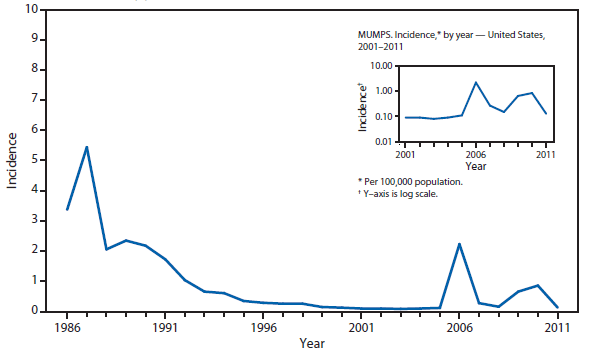

To prevent measles among U.S. residents, health-care providers should follow ACIP vaccination recommendations (4), ensuring that travelers are vaccinated, particularly infants aged 6–11 months, and that 2 doses are administered for those aged ≥12 months. In addition, parents should be educated about the risk for measles associated with international travel. Information on vaccination recommendations for travelers is available from CDC at http://www.cdc.gov/travel.