Intestinal Capillariasis

[Capillaria philippinensis]

Causal Agent

The nematode (roundworm) Capillaria (=Paracapillaria) philippinensis causes human intestinal capillariasis. Unlike C. hepatica, humans are most likely the main definitive host. Transmission occurs primarily through eating undercooked fish.

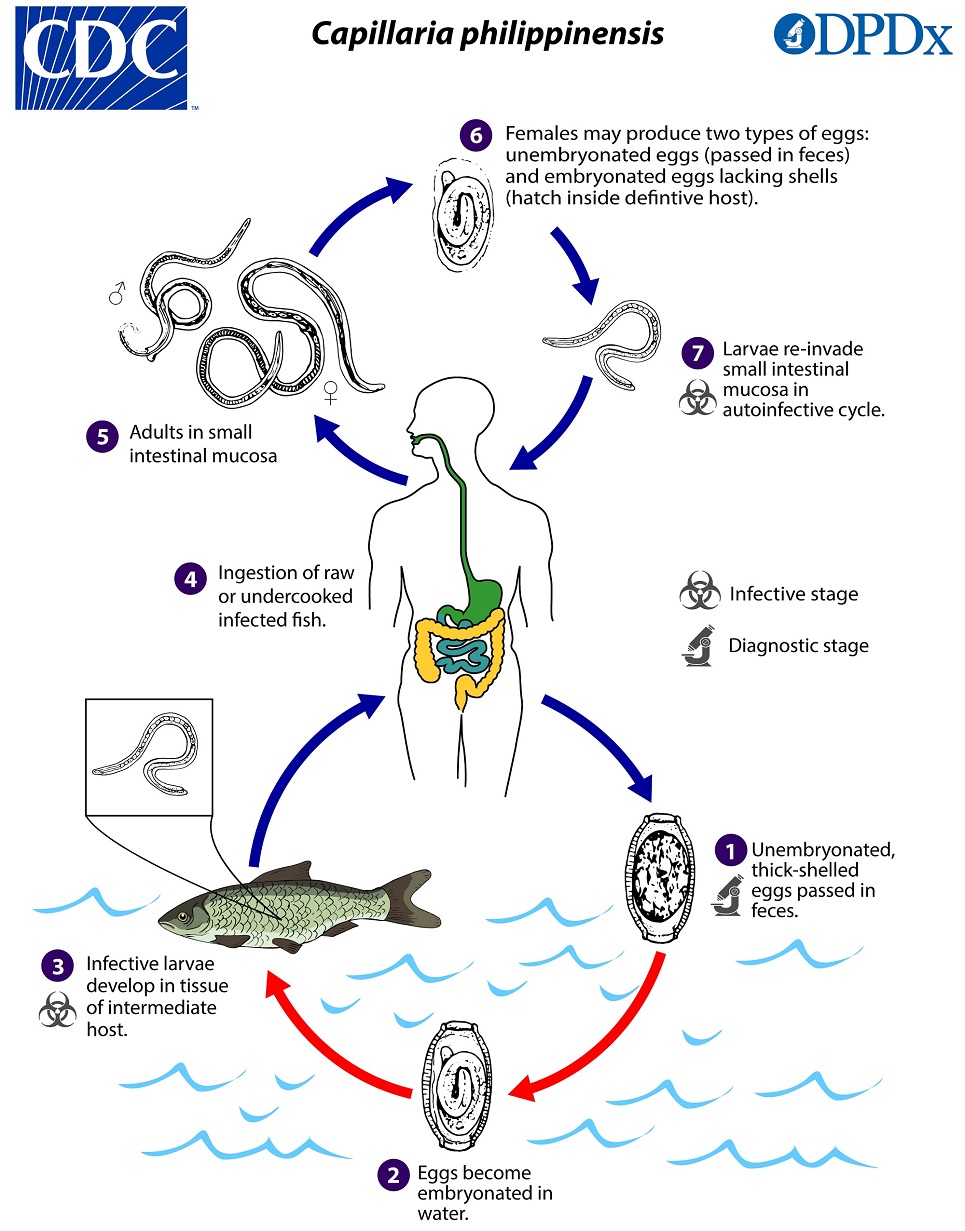

Life Cycle

Typically, unembryonated, thick-shelled eggs are passed in the human stool  and become embryonated in the external environment in 5—10 days

and become embryonated in the external environment in 5—10 days  ; after ingestion by freshwater fish, larvae hatch, penetrate the intestine, and migrate to the tissues

; after ingestion by freshwater fish, larvae hatch, penetrate the intestine, and migrate to the tissues  . Ingestion of raw or undercooked fish results in infection of the human host.

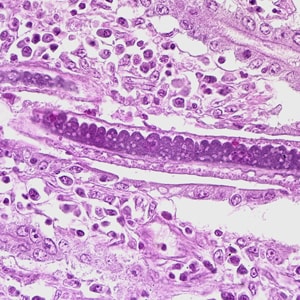

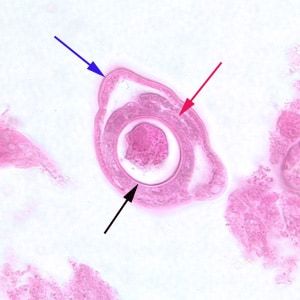

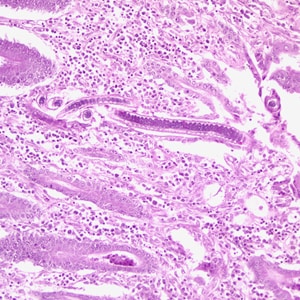

. Ingestion of raw or undercooked fish results in infection of the human host.  The adults of Capillaria philippinensis are very small (males: 2.3 to 3.2mm; females: 2.5 to 4.3 mm) and reside in the human small intestine, where they burrow in the mucosa

The adults of Capillaria philippinensis are very small (males: 2.3 to 3.2mm; females: 2.5 to 4.3 mm) and reside in the human small intestine, where they burrow in the mucosa  . In addition to the unembryonated, shelled eggs which pass into the environment, the females can also produce eggs lacking shells (possessing only a vitelline membrane)

. In addition to the unembryonated, shelled eggs which pass into the environment, the females can also produce eggs lacking shells (possessing only a vitelline membrane)  , which become embryonated within the female’s uterus or in the intestine. The released larvae can re-invade the intestinal mucosa and cause internal autoinfection

, which become embryonated within the female’s uterus or in the intestine. The released larvae can re-invade the intestinal mucosa and cause internal autoinfection  . This process may lead to hyperinfection (a massive number of adult worms).

. This process may lead to hyperinfection (a massive number of adult worms).

Hosts

While piscivorous birds have been suggested as a wildlife reservoir of C. philippinensis, this has not been well substantiated based on field observations. Experimental trials have established heavy patent infections in several bird species (particularly herons, egrets, and bitterns), but extensive surveys of wild birds in endemic areas have largely failed to detect infection. Many species of freshwater fish appear susceptible to infection and act as intermediate hosts.

Geographic Distribution

As the name suggests, Capillaria philippinensis is endemic in the Philippines and epidemics have occurred in the Northern Luzon region. The parasite is also endemic in Thailand, and sporadic cases have been reported from other East and Southeast Asian countries. More recently, a number of cases have been identified in northern Egypt.

Clinical Presentation

Intestinal capillariasis initially manifests as abdominal/gastrointestinal disease, which can become serious if not treated because of autoinfection. A protein-losing enteropathy can develop which may result in complications such as cardiomyopathy, severe emaciation, cachexia, and death. In the first recognized outbreak of intestinal capillariasis, the case fatality rate was over 10%.

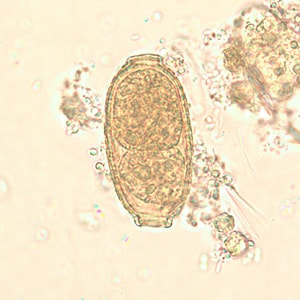

Capillaria philippinensis eggs are 35 to 45 µm in length by 20-25 µm in width, somewhat smaller than C. hepatica. They have two flat polar prominences and a striated shell. Eggs are unembryonated when passed in feces.

Capillaria philippinensis adult males are 2.0—3.5 mm in length and females are 2.5—4.5 mm in length. Females may contain embryonated or unembryonated eggs in utero.

Diagnostic Findings

The specific diagnosis of C. philippinensis is established by finding eggs, larvae and/or adult worms in the stool or in intestinal biopsies. Unembryonated eggs are the typical stage found in the feces. In severe infections, embryonated eggs, larvae, and even adult worms can be found in the feces. No valid serologic testing is available for diagnosis.

More on: Morphologic comparison with other intestinal parasites

Laboratory Safety

Standard precautions apply when processing stool samples. Eggs of C. philippinensis are not infectious to humans.

Suggested Reading

Sadaow, L., Sanpool, O., Intapan, P.M., Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W., Prasongdee, T.K. and Maleewong, W., 2018. A Hospital-Based Study of Intestinal Capillariasis in Thailand: Clinical Features, Potential Clues for Diagnosis, and Epidemiological Characteristics of 85 Patients. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine And Hygiene, 98(1), pp.27-31.

Lu, L.H., Lin, M.R., Choi, W.M., Hwang, K.P., HSU, Y.H., Bair, M.J., Liu, J.D., Wang, T.E., Liu, T.P. and Chung, W.C., 2006. Human intestinal capillariasis (Capillaria philippinensis) in Taiwan. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine And Hygiene, 74(5), pp.810-813.

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.