Cercarial Dermatitis

Causal Agents

Cercarial dermatitis (“swimmer’s itch”, “clam-digger’s itch”, “duck itch”) is caused by the cercariae of certain species of schistosomes whose normal hosts are birds and mammals other than humans. These cercariae seem to have a chemotrophic reaction to secretions from the skin and are not as host-specific as other types of human-infecting schistosomes. Skin penetration by these zoonotic cercariae causes dermatitis, but the cercariae do not mature into adults in the human body.

Several genera/species are known to cause cercarial dermatitis; the most commonly implicated genus globally is the waterfowl schistosome Trichobilharzia spp. (T. ocellata, T. brevis, T. stagnicolae, T. physellae, T. regenti, and others). Other avian schistosomes that cause cercarial dermatitis include Ornithobilharzia spp., Austrobilharzia spp. (A. ), Bilharziella polonica, and Gigantobilharzia huronensis. Cases involving mammalian schistosomes Heterobilharzia americana, Bivitellobiharzia spp., Schistosomatium spp., and some aberrant zoonotic Schistosoma spp. (S. spindale, S. (=Orientobilharzia) turkestanicum) occur occasionally. These schistosomes all use different snail intermediate hosts, commonly those from the families Nassariidae, Lymnaeidae, and Physidae.

Cercarial dermatitis should not be confused with seabather’s eruption, which is caused by the larval stage of cnidarians (e.g., jellyfish). The areas of skin affected by seabather’s eruption is generally under the garments worn by bathers and swimmers where the organisms are trapped after the person leaves the water. Cercarial dermatitis occurs on the exposed skin outside of close-fitting garments.

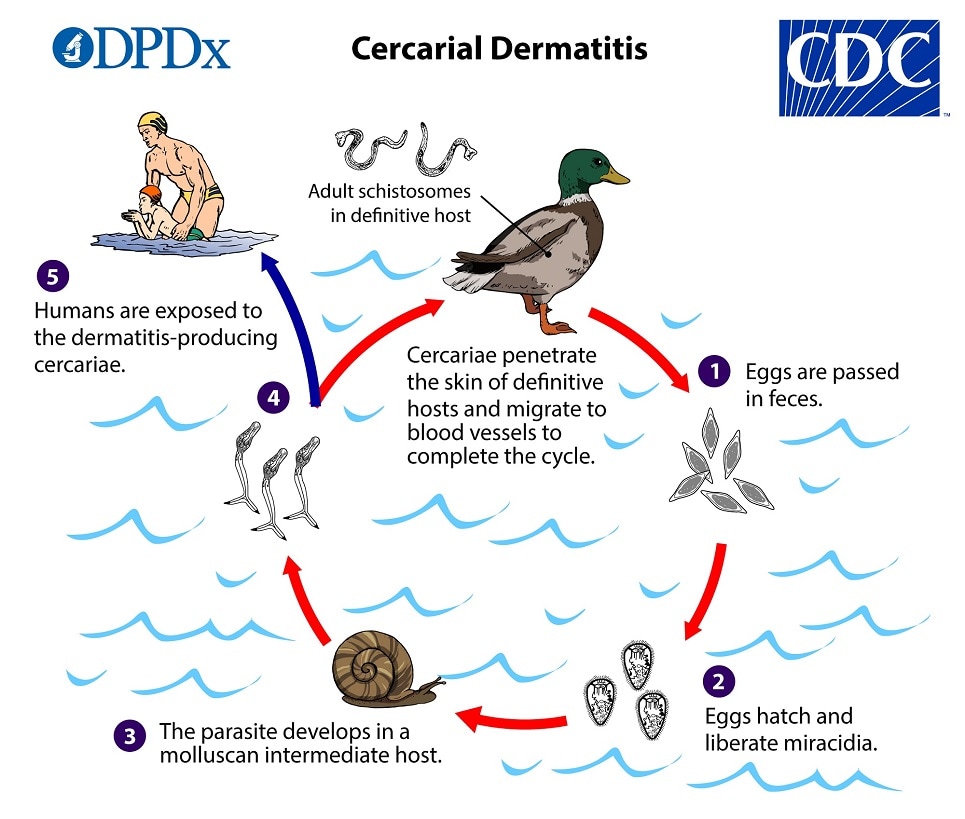

Life Cycle

Adult worms are found in the blood vessels of definitive hosts and produce eggs that are passed in the feces  On exposure to water, the eggs hatch and liberate a ciliated miracidium that infects a suitable snail (gastropod) intermediate host

On exposure to water, the eggs hatch and liberate a ciliated miracidium that infects a suitable snail (gastropod) intermediate host  . The parasite develops in the intermediate host

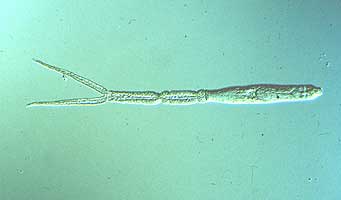

. The parasite develops in the intermediate host  to produce free-swimming cercariae that are released under appropriate conditions and penetrate the skin of the birds and migrate to the blood vessels to complete the cycle

to produce free-swimming cercariae that are released under appropriate conditions and penetrate the skin of the birds and migrate to the blood vessels to complete the cycle  . Humans are inadvertent and inappropriate hosts; cercariae may penetrate the skin but do not develop further

. Humans are inadvertent and inappropriate hosts; cercariae may penetrate the skin but do not develop further  . A number of species of trematodes with dermatitis-producing cercariae have been described from both freshwater and saltwater environments, and exposure to either type of cercaria will sensitize persons to both.

. A number of species of trematodes with dermatitis-producing cercariae have been described from both freshwater and saltwater environments, and exposure to either type of cercaria will sensitize persons to both.

Hosts

Though some schistosomes of mammals cause cercarial dermatitis, the vast majority involved are of avian origin, and many of which exhibit relatively low specificity among bird hosts. For example, Trichobilharzia spp. are often associated with anseriform birds (e.g. ducks, geese) and Austrobilharzia spp. with many species of anseriforms, wading birds, and seabirds. Gigantobilharzia spp. have been identified in goldfinches, starlings, pelicans, cardinals, crows, canaries, and more. Among the more well-described dermatitis-causing mammalian schistosomes, Heterobilharzia americana is found in dogs and raccoons, and Schistosoma spindale normally infects ruminant livestock. Snail intermediate hosts are diverse and will depend on the parasite species and the habitat of the definitive host.

Geographic Distribution

Cercarial dermatitis occurs worldwide with cases reported from every inhabited continent. Many species are widespread due to the migration of suitable bird hosts and introduction of snail intermediate hosts. In the United States, cases are commonly reported from the Great Lakes region.

Agents of cercarial dermatitis exist in both marine and freshwater environments. Freshwater species include Trichobilharzia spp., Gigantobilharzia huronensis, Bilharziella polonica, Heterobilharzia americana, Schistosomatium spp., and Bivitellobiharzia spp. Marine (saltwater or brackish) species include Austrobilharzia spp. and Ornithobilharzia spp.

Clinical Presentation

Cercarial dermatitis (swimmer’s itch) is a cutaneous inflammatory response usually associated with penetration of the skin by cercariae of bird schistosomes. Symptoms include reddening and itching of exposed skin in the water or immediately after emerging. This is an indication of initial penetration of the cercariae. After a period of approximately 12 hours, pruritic papules may become vesicular. Scratching the affected areas may result in secondary bacterial infections. An interesting note is that previous contact with cercariae can lead to a more immediate and intense immune response.

Proper identification of cercariae which may cause cercarial dermatitis is best left to investigators with a good background in trematode morphology as well as malacology.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Cercarial dermatitis is usually diagnosed based on symptoms and not laboratory analyses of clinical specimens. Investigation into the causal agent rarely occurs except during outbreaks. In these cases, specific snails that would be suitable hosts for these particular schistosomes need to be collected from the area where cases of cercarial dermatitis have been reported. The cercariae then must be identified by experts as being a type that can cause cercarial dermatitis by using appropriate reference material. PCR can also be used to identify species using cercariae or infected snail tissue.

Lab Safety

Universal laboratory precautions apply. Infectious cercariae are unlikely to be handled in a human clinical diagnostic laboratory.

Suggested Reading

Horák, P., Mikeš, L., Lichtenbergová, L., Skála, V., Soldánová, M. and Brant, S.V., 2015. Avian schistosomes and outbreaks of cercarial dermatitis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 28 (1), pp.165-190.

Verbrugge, L.M., Rainey, J.J., Reimink, R.L. and Blankespoor, H.D., 2004. Swimmer’s itch: incidence and risk factors. American Journal of Public Health, 94 (5), pp.738-741.

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.