Background for CDC’s Updated Respiratory Virus Guidance

Executive summary

The 2023-2024 fall and winter virus season, four years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, provided ongoing evidence of the changing face of respiratory diseases. COVID-19 remains an important public health threat, but it is no longer the emergency that it once was, and its health impacts increasingly resemble those of other respiratory viral illnesses, including influenza and RSV. This reality enables CDC to provide updated guidance proportionate to the current level of risk COVID-19 poses while balancing other critical health and societal needs. Key drivers and indicators of the reduction in threat from COVID-19 include:

- Due to the effectiveness of protective tools and high degree of population immunity, there are now fewer hospitalizations and deaths due to COVID-19. Weekly hospital admissions for COVID-19 have decreased by more than 75% and deaths by more than 90% compared to January 2022, the peak of the initial Omicron wave. Complications like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) are now also less common, and prevalence of Long COVID also appears to be decreasing. These reductions in disease severity and death have persisted through a full respiratory virus season following the expiration of the federal Public Health Emergency for COVID-19 and its associated special measures on May 11, 2023.

- Protective tools, like vaccines and treatments, that decrease risk of COVID-19 disease (particularly severe disease) are now widely available. COVID-19 vaccination reduces the risk of symptomatic disease and hospitalization by about 50% compared to people not up to date on vaccination. Over 95% of adults hospitalized in 2023-2024 due to COVID-19 had no record of receiving the latest vaccine. Treatment with nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (Paxlovid) in persons at high risk of severe disease has been shown to decrease risk of hospitalization by 75% and death by 60% in recent studies.

- There is a high degree of population immunity against COVID-19. More than 98% of the U.S. population now has some degree of protective immunity against COVID-19 from vaccination, prior infection, or both.

As the threat from COVID-19 becomes more similar to that of other common respiratory viruses, CDC is issuing Respiratory Virus Guidance, rather than additional virus-specific guidance. This brings a unified, practical approach to addressing risk from a range of common respiratory viral illnesses, such as influenza and RSV, that have similar routes of transmission and symptoms and similar prevention strategies. The updated guidance on steps to prevent spread when you are sick particularly reflects the key reality that many people with respiratory virus symptoms do not know the specific virus they are infected with. Importantly, states and countries that have already shortened recommended isolation times have not seen increased hospitalizations or deaths related to COVID-19. Although increasingly similar to other respiratory viruses, some differences remain, such as the risk of post-COVID conditions.

CDC will continue to evaluate available evidence to ensure the recommendations in the guidance provide the intended protection. This includes monitoring data to identify and model patterns in respiratory virus transmission, severity, hospitalizations, deaths, virus evolution, and Long COVID. In addition, CDC continues to make systems-level investments to protect the American public. Examples include measuring and enhancing effectiveness and uptake of vaccines and antiviral treatments, particularly for those at increased risk for severe disease; integrating healthcare and public health systems to prevent, identify, and respond to emerging public health threats more rapidly; and strengthening partnerships across sectors to ensure a strong public health infrastructure.

- The Respiratory Virus Guidance covers most common respiratory viral illnesses but should not supplant specific guidance for pathogens that require special containment measures, such as measles. However, the recommendations in this guidance may still help reduce spread of various other types of infections. The guidance may not apply in certain outbreak situations when more specific guidance may be needed.

- CDC offers separate, specific guidance for healthcare settings (COVID-19, flu, and general infection prevention and control)

Transitioning from an emergency state

Since 2020, CDC provided guidance specific to COVID-19, initially with detailed recommendations on many issues and for specific settings. Throughout 2022 and 2023, CDC revised COVID-19 public health recommendations as the pandemic evolved. These changes to the guidance reflected the latest scientific evidence as well as the progression through the pandemic. The expiration of the federal Public Health Emergency for COVID-19 in 2023 also reflected a shift away from the emergency response phase to the recovery and maintenance phases in which COVID-19 is addressed amidst many other public health threats. Measures appropriate to an emergency setting are less relevant after the emergency ended.

The continuum of pandemic phases

Changing risk environment

In developing this updated Respiratory Virus Guidance, CDC carefully considered the changing risk environment, particularly lower rates of severe disease from COVID-19 and increased population immunity, as well as improvements in other prevention and control strategies.

Trends in outcomes

Hospitalizations

In 2024, COVID-19 is less likely to result in severe disease than earlier in the pandemic because of greater immunity from vaccines and previous infections and greater treatment availability.

COVID-19 remains a greater cause of severe illness and death than other respiratory viruses, but the differences between these rates are much smaller than they were earlier in the pandemic. This difference is even smaller among people admitted to the hospital. Studies show the proportion of adults hospitalized with COVID-19 (15.5%) or influenza (13.3%) who were subsequently admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) was similar, and patients 60 years and older hospitalized with RSV were 1.5 times more likely to be admitted to the ICU than those with COVID-19.

Hospital admissions for COVID-19 peaked in January 2022 with more than 150,000 admissions per week, based on data from CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) covering all U.S. hospitals. During the week ending February 17, 2023, there were 18,977 hospital admissions for COVID-19. During this same week, there were 10,480 hospital admissions for influenza.

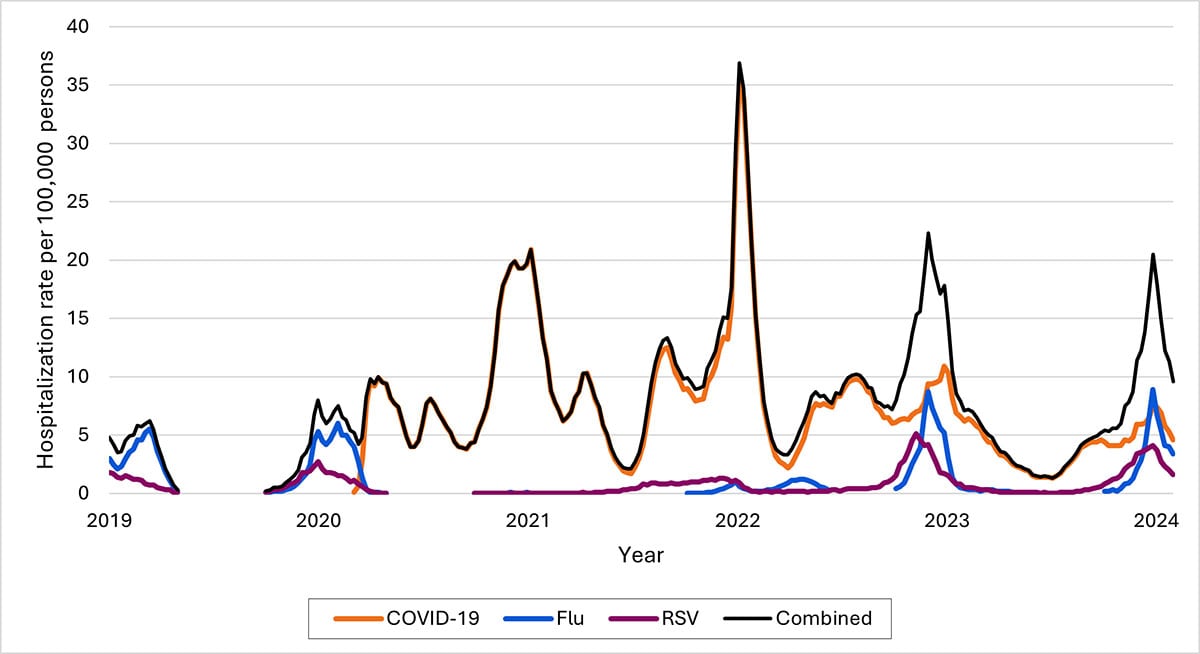

Another data source—called Respiratory Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RESP-NET) — collects hospitalization data on 8–10% of the U.S. population since before pandemic. The RESP-NET figures below demonstrate how COVID-19 hospitalizations have decreased over time and are now in the range of those for influenza and RSV.

COVID-19 hospitalizations have been declining year-over-year since 2022, with winter peaks more closely resembling those of influenza

Data on weekly new hospital admissions of patients with COVID-19, influenza, and RSV from surveillance sites in the Respiratory Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RESP-NET), which cover 8–10% of the U.S. population, October 2019–February 2024.

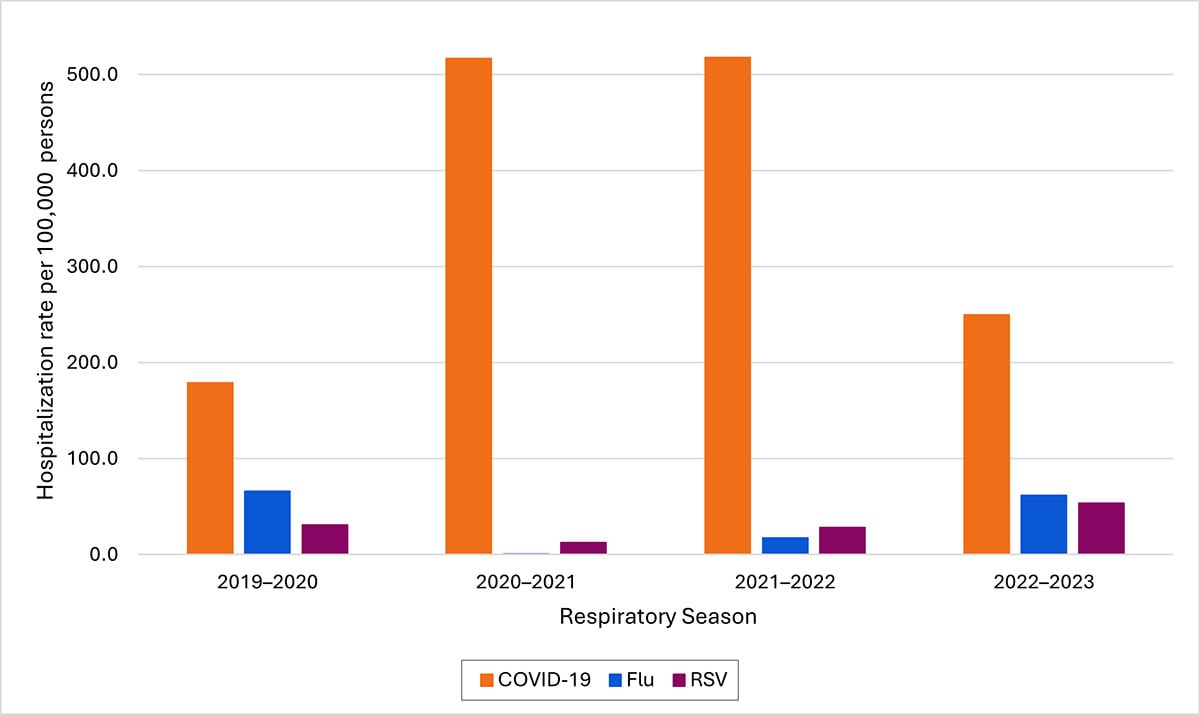

Cumulative annual rates of COVID-19-associated hospitalizations (Oct. 1–Sept. 30 to align with start of typical fall and winter virus season) have declined since 2021–2022

*Hospitalization rates per 100,000 population. Data from the Respiratory Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RESP-NET) are preliminary and subject to change as more data become available. As data are received each week, prior case counts and rates are updated accordingly. Hospitalizations rates are likely to be underestimated as some hospitalizations might be missed because of undertesting, differing provider or facility testing practices, and diagnostic test sensitivity. Rates presented do not adjust for testing practices, which may differ by pathogen, age, race and ethnicity, and other demographic criteria. Surveillance for each pathogen was not conducted during the same time periods each season. For all seasons displayed, all three platforms conduct surveillance between October 1 and April 30 of each year. Surveillance for influenza hospitalizations was extended to June 11, 2022, for the 2021–2022 season, but otherwise occurred October through April each season. Surveillance for RSV hospitalizations occurred from October 2019 through April 2020. Since October 2020, surveillance for RSV hospitalizations has occurred year-round excluding May–June 2022. Surveillance for COVID-19 hospitalizations has occurred year-round since March 2020. Cumulative rates for the 2023–2024 season are not presented as surveillance is ongoing.

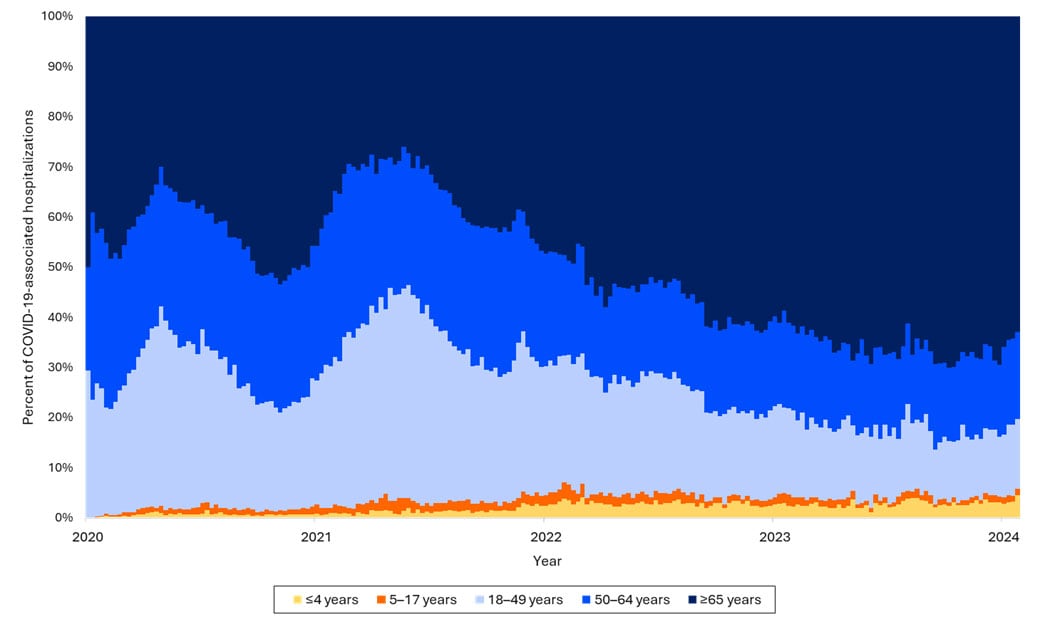

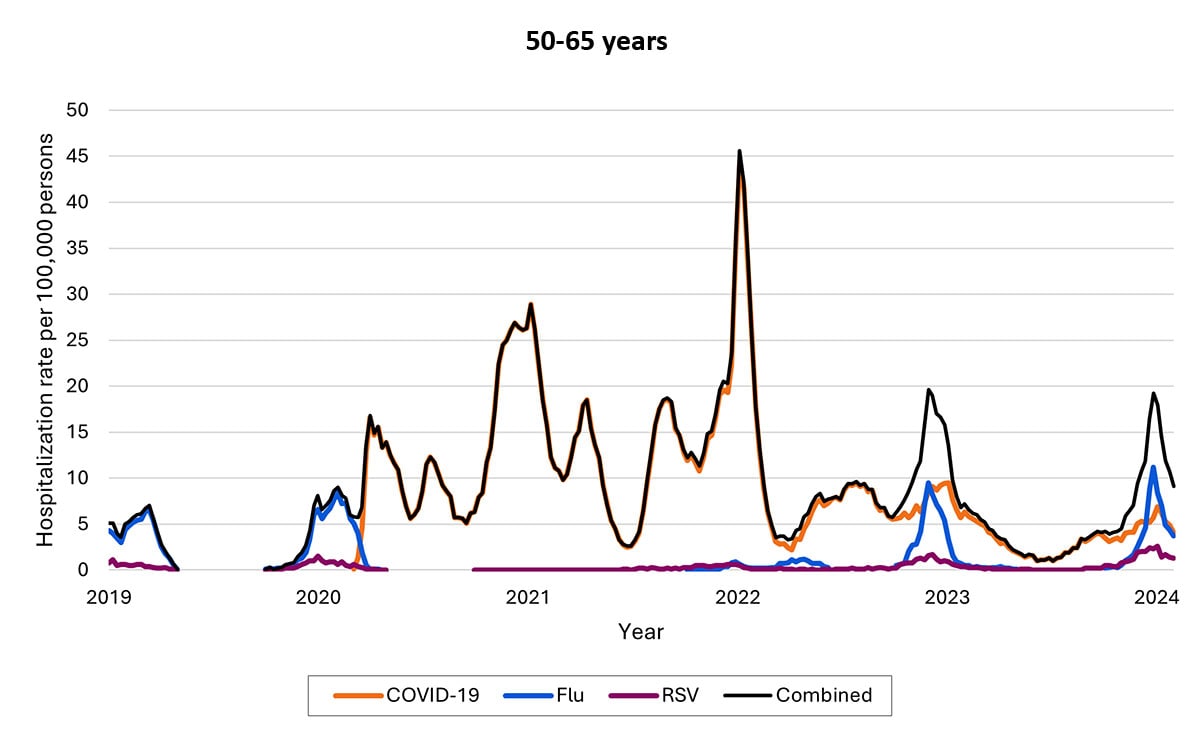

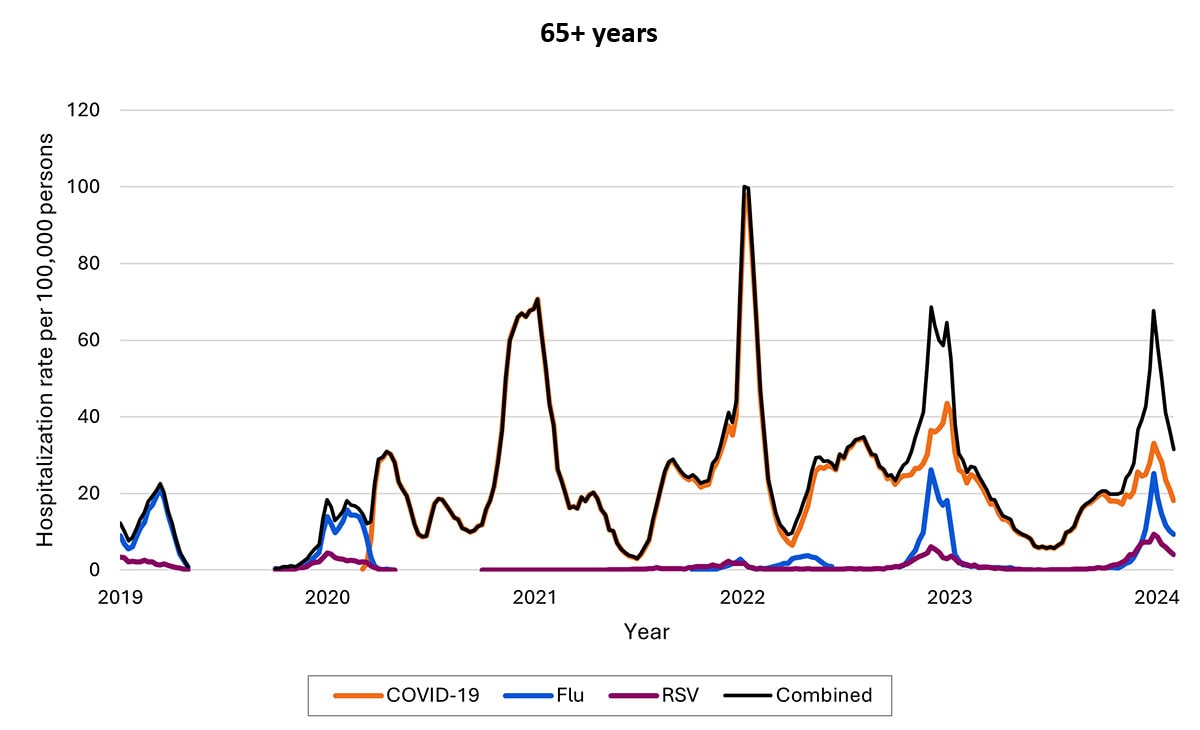

Hospitalizations by age group. Over time, rates of hospitalization for COVID-19 have decreased across all ages but have remained higher among adults ages ≥65 years relative to younger adults, children, and adolescents. Among older children, rates have decreased, and rates among children are now highest among infants ages <6 months. As of the end of December 2023, about 70% of hospitalizations were among people ages ≥65 years, and 14% were among those ages 50–64 years.

Increasing proportion of COVID-19 hospitalizations are in older adults, as well as the youngest children

Percents of weekly COVID-19-associated hospitalizations, by age group — COVID-NET, March 1, 2020–January 27, 2024

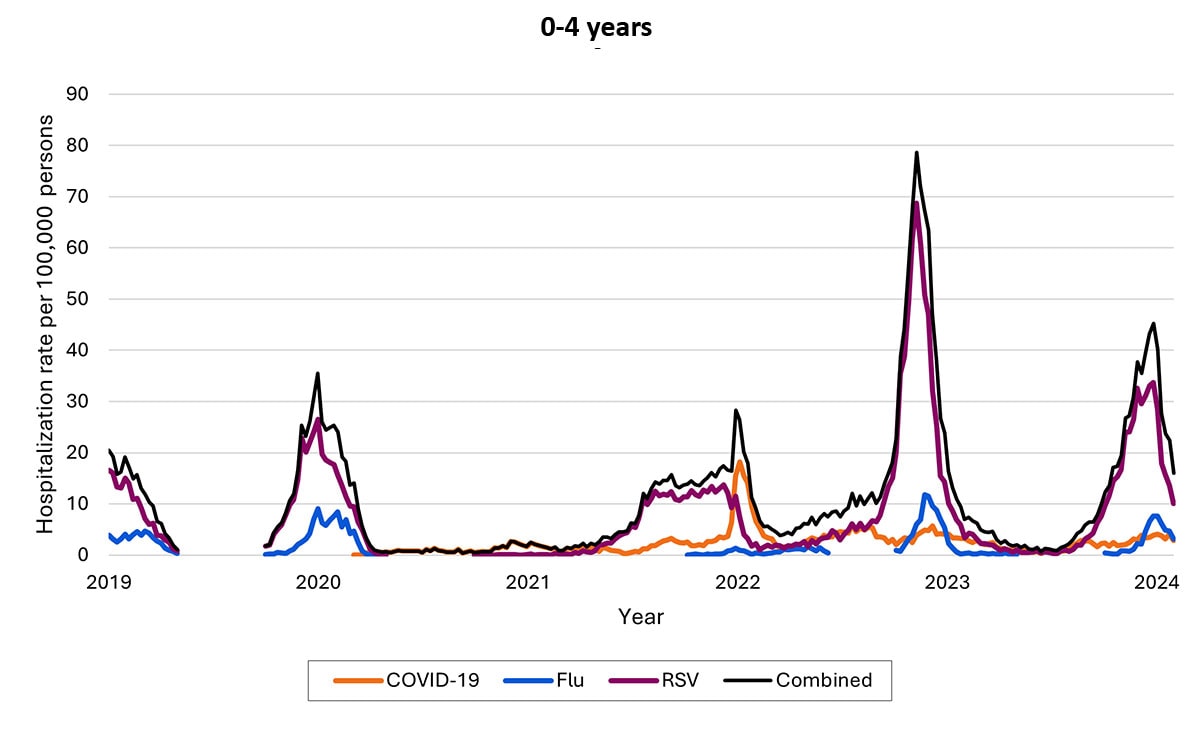

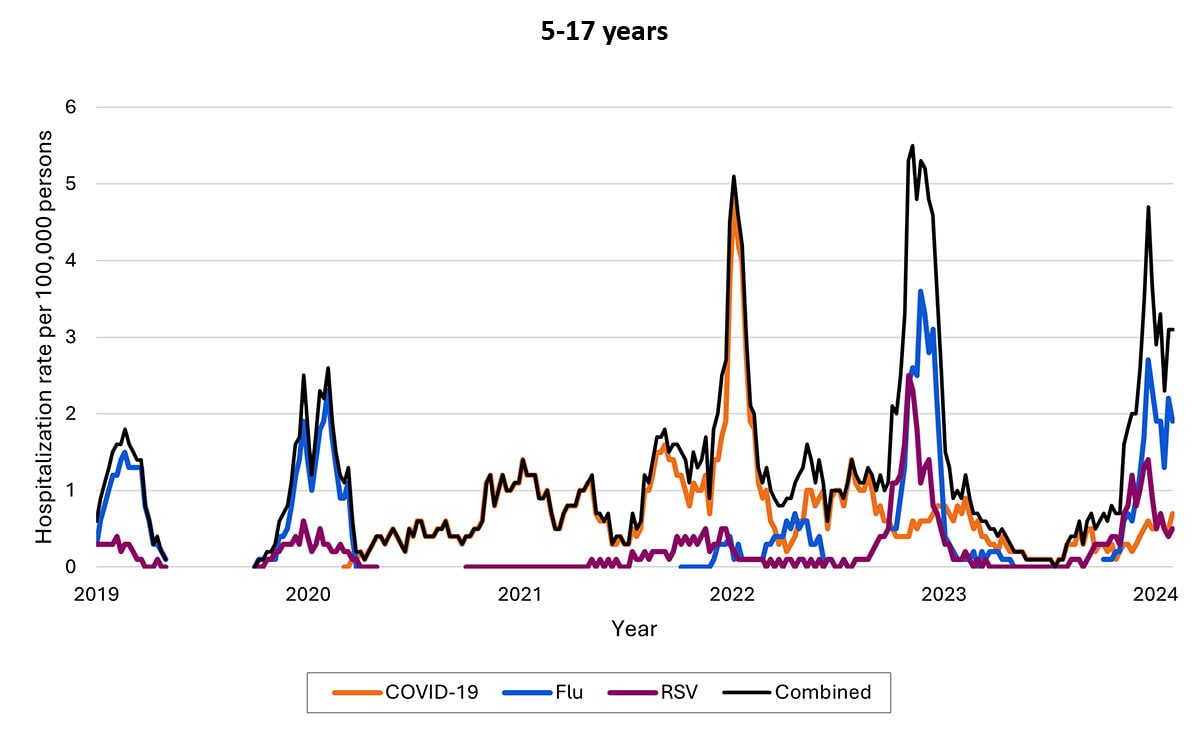

The proportion of hospitalizations caused by each of these viruses in the 2022–2023 season varied by age group. Among children <5 years RSV caused the most hospitalizations. Among children and adolescents 5–17 years, influenza caused the most hospitalizations, and hospitalizations overall were the lowest in this age group. Among adults, COVID-19-associated hospitalizations were higher than those for influenza or RSV. These patterns have been broadly consistent thus far in the 2023-2024 season.

Most COVID-19, influenza, and RSV hospitalizations are in older adults and young children, with COVID-19 highest among older adults and RSV highest among young children (note differences in y-axis rates of hospitalizations across age groups)

Weekly rates of laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus-associated hospitalizations by age, 2022–2023 season. Seasonal influenza surveillance ended in April 2023 for the 2022–2023 seasons; surveillance for COVID-19 and RSV hospitalizations was year-round. Data from RESP-NET.

Deaths

As of February 10, 2024, 1,178,527 deaths from COVID-19 have been reported in the United States. In 2021 COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death (12% of all deaths) and in 2022 it was the fourth leading cause of death (5.7% of all deaths), following heart disease, cancer, and unintentional injury. In preliminary data from 2023, COVID-19 was the 10th leading cause of death. Among deaths from COVID-19 occurring from January–September 2023, 88% were among people ≥65 years.

COVID-19 is increasingly a contributing rather than the primary (underlying) cause of death. In 2020, COVID-19 was listed as the primary cause for 91% of deaths involving COVID-19. During January–September 2023, that number had fallen to 69%.

Reported deaths involving COVID-19 are several-fold greater than those reported to involve influenza and RSV. However, influenza and likely RSV are often underreported as causes of death. CDC estimates that from October 1, 2023, to February 17, 2024, 17,000–50,000 influenza deaths occurred, several times greater than the number of reported deaths. As such, the data on reported deaths should be interpreted with caution when assessing the true burden of deaths and comparing across diseases.

Current estimates of total COVID-19 deaths are not available, but COVID-19 deaths are not likely to be as underreported as are deaths involving influenza because of widespread COVID-19 testing and intensive focus on COVID-19 during the pandemic. Total COVID-19 deaths, accounting for underreporting, are likely to be higher than, but of the same order of magnitude as, total influenza deaths. Supporting this idea, the cumulative rate of COVID-19-associated hospitalizations during October 1, 2023–February 3, 2024, was 97 per 100,000 population, compared with 52 per 100,000 influenza-associated hospitalizations and 44 per 100,000 RSV hospitalizations. In-hospital death was about 1.8 times higher for COVID-19-associated hospitalizations (4.6%) vs. those for influenza (2.6%).

COVID-19-associated deaths based on reports on death certificates declined over 5-fold since their peak in 2020-2021 and are now at the same order of magnitude as estimated influenza deaths

| Year corresponding with start of influenza season (Oct. 1- Sept. 30) | Reported COVID-19 deaths* | Reported influenza deaths | Estimated influenza deaths** | Reported RSV deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-2019 | 0 | 7,181 | 19,000–96,000 | 243 |

| 2019-2020 | 208,601 | 9,432 | 17,000–85,000 | 345 |

| 2020-2021 | 517,783 | 876 | Not estimated | 85 |

| 2021-2022 | 331,885 | 2,856 | 4,000–24,000 | 396 |

| 2022-2023 | 89,573 | 9,559 | 18,000–97,000 | 736 |

| 2023-2024 (through Feb. 17) | 32,949 to date | 5,854 to date | 17,000–50,000 to date | 587 to date |

*Reported death data from CDC’s National Vital Statistics System based on death certificates, available at CDC WONDER. Data from 2022-2024 are provisional and subject to change.

****Estimated influenza deaths, accounting for underreporting, based CDC modeling available here: Disease Burden of Flu, including confidence intervals. It has been long recognized that only counting deaths where influenza was recorded on death certificates would underestimate influenza’s overall impact on mortality. Influenza can lead to death from other causes, such as pneumonia and congestive heart failure; however, it may not be listed on the death certificate as a contributing cause for multiple reasons, including a lack of testing. Therefore, CDC has an established history of using models to estimate influenza-associated death totals. While under-reporting of deaths attributed to RSV and COVID-19 likely also occurs, regularly updated model estimates are currently not available. Modeled burden estimates for influenza are not directly comparable to death certificate derived counts for COVID-19 and RSV.

Divergence between infection and severe disease

Although hospitalizations and deaths involving COVID-19 have declined substantially since 2022, rates of infections with the virus have not. For example, the percentage of SARS-CoV-2 tests that are positive, a key indicator of community spread, reached peak levels of 14.6% in August 2023 and 12.9% in January 2024, similar to the peak levels observed in earlier years. Differences in testing practices between time periods might influence these data, but these high levels of test positivity are consistent with high levels also seen in wastewater.

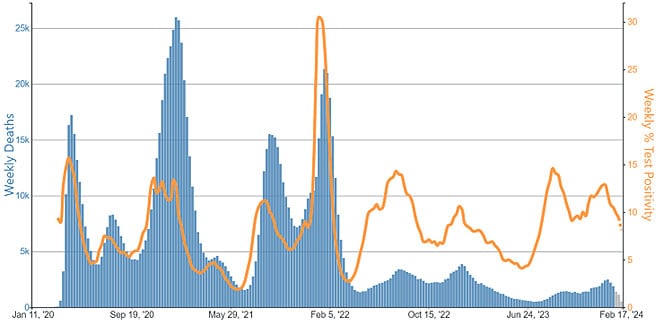

SARS-CoV-2 test positivity (orange line) has remained elevated, a marker of ongoing COVID-19 spread, but deaths (blue bars) have declined substantially

Provisional COVID-19 Deaths and COVID-19 Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT) Percent Positivity, by Week, in The United States, Reported to CDC. Sources: Provisional Deaths from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) Figure from CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

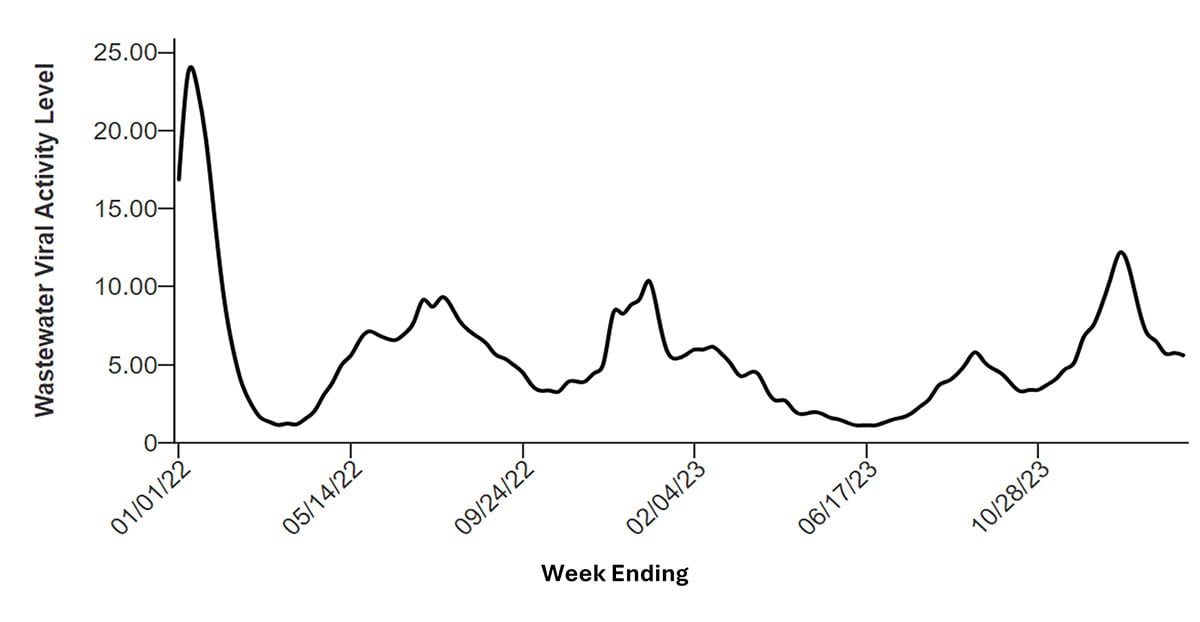

Wastewater viral activity levels of SARS-CoV-2 demonstrate ongoing community transmission

Figure from CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System

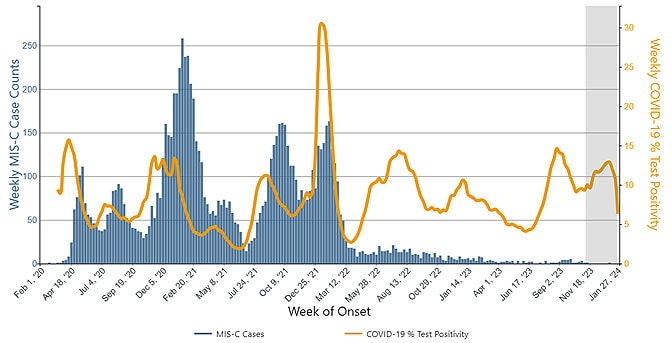

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

MIS-C is a rare but serious condition associated with COVID-19 in which different parts of the body become inflamed. As of January 2024, more than 9,600 cases of MIS-C have been reported to CDC, including 79 children who died. Before March 2022, the end of the initial Omicron wave, most weekly totals of MIS-C cases exceeded 50, with some weeks involving >150 cases. The number of cases declined substantially after that point, with no week exceeding 25 cases. The reduction in MIS-C cases is likely due to multiple factors, including an increase in population immunity from both infection and vaccination, as well as differences in development of MIS-C associated with SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Weekly U.S. MIS-C cases (blue bars) have declined markedly despite ongoing high levels of COVID-19 test positivity (orange line)

Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions

CDC broadly defines Long COVID as signs, symptoms, and conditions that continue or develop ≥4 weeks after COVID-19. It can include a wide range of health conditions that can last weeks, months, or years. Although COVID-19 is becoming more similar to influenza and RSV in terms of hospitalizations and death over time, important differences remain, like the potential for these post-infection conditions. Long COVID occurs more often in people who had severe COVID-19 illness but can occur in anyone who has been infected with SARS-CoV-2, including children and people who were asymptomatic. Estimates of Long COVID vary widely and can differ based on study methods and how long after infection symptoms were assessed. Based on the nationally representative 2022 National Health Interview Survey, 3.4% of adults reported Long COVID and 0.5% of children. In Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Surveys, one quarter of people currently reporting Long COVID reported significant activity limitations.

Accumulating evidence suggests that vaccination prior to infection can reduce the risk of Long COVID. There is mixed evidence on whether the use of antivirals, including nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (Paxlovid), during the time of acute infection can reduce the risk of Long COVID. Decreases in Long COVID prevalence have been reported in several countries including the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, likely due to less severe illness from COVID-19 overall, protection from vaccines, and possible changes in risk with new variants.

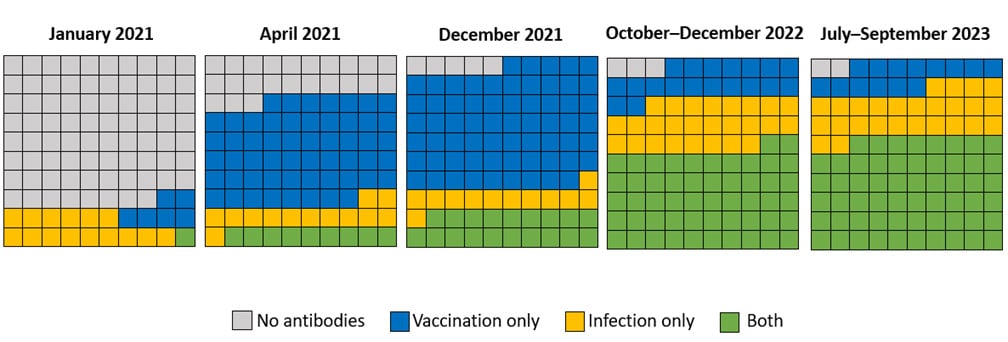

Increase in population immunity against COVID-19

Now, more than ever before, most people have some degree of protection because of underlying immunity. Data from a national longitudinal cohort of blood donors aged ≥16 years provide insight on the proportion of the population with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 from infection, vaccination, or both (referred to as hybrid immunity). Hybrid immunity has been described as providing better protection with longer durability against severe illness compared to immunity from vaccination or infection alone.

In January 2021, only an estimated 22% of people aged ≥16 years had antibodies against COVID-19. By the third quarter of 2023 (July–September), 98% had antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, with 14% from vaccination alone, 26% from infection alone, and 58% from both. An estimated 96% of children aged 6 months to 17 years had antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in November–December 2022, including 92% with antibodies from a prior infection, according to blood samples from commercial laboratories. Although immunity against SARS-CoV-2 tends to decline from high levels initially generated by vaccination and infection, substantial protection persists for much longer, especially against the most severe outcomes like requiring a ventilator and death. New data show that the 2023–2024 updated COVID-19 vaccine can provide an additional layer of protection against severe disease.

Prevalence of vaccine-induced and infection-induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among a cohort of U.S. blood donors ≥16 years

Immunizations

As of February 3, 2024, 22% of adults reported they had received an updated 2023-2024 vaccine, including 42% of people aged ≥65 years. Vaccine uptake varies geographically and by other demographics. As of February 11, 2024, 40% of nursing home residents were up to date with a COVID-19 vaccine.

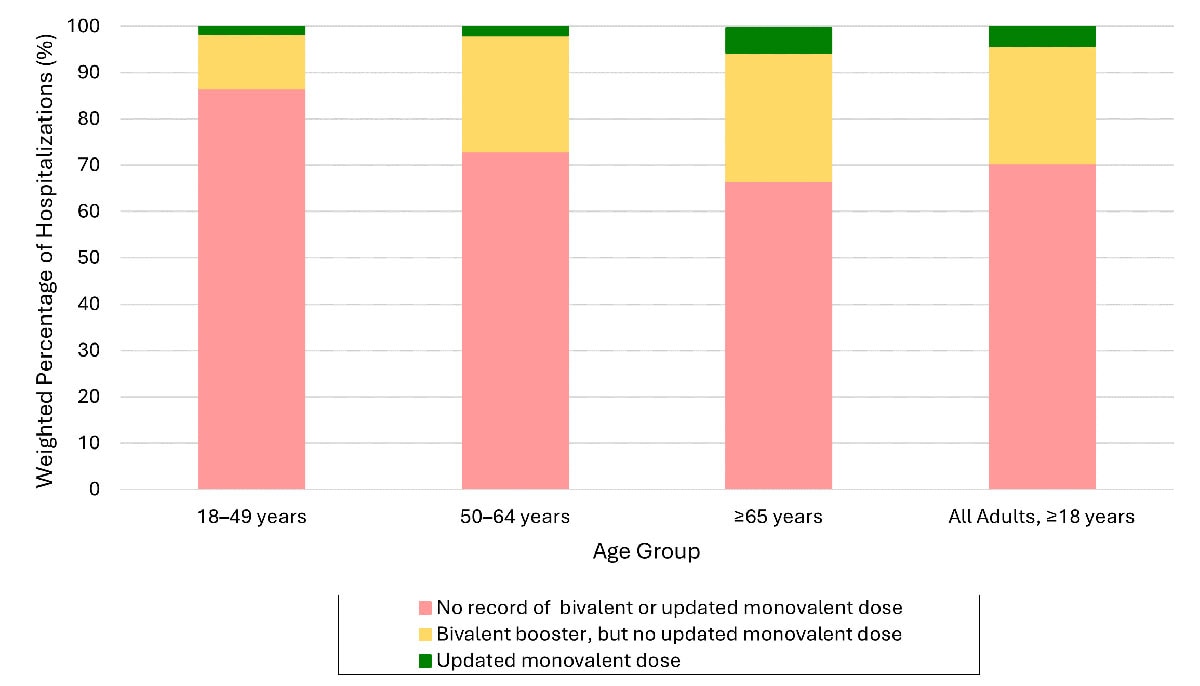

Reductions in COVID-19-associated hospitalizations over time could be even greater if more people, especially those at greater risk, receive updated COVID-19 vaccines. Among adults with COVID-19-associated hospitalizations during October–November 2023, over 95% had not received an updated (2023–2024) COVID-19 vaccine, and most (70%) had also not received an updated vaccine from the previous year (2022–2023).

Over 95% of adults hospitalized with COVID-19 during October–November 2023 had not received an updated (2023–2024) COVID-19 vaccine (Preliminary)

Data from COVID-NET. Data are preliminary as they only include two months of hospitalization data for which the updated monovalent vaccine dose was recommended. Continued examinations of vaccine registry data are ongoing. No record of bivalent or updated monovalent dose: No recorded doses of COVID-19 bivalent or updated 2023-2024 monovalent dose. Bivalent booster, but no updated monovalent doses: Received COVID-19 bivalent booster vaccination but no record of receiving updated 2023-2024 monovalent booster dose. Updated monovalent dose: Received updated 2023-2024 monovalent dose. Persons with unknown vaccination status are excluded.

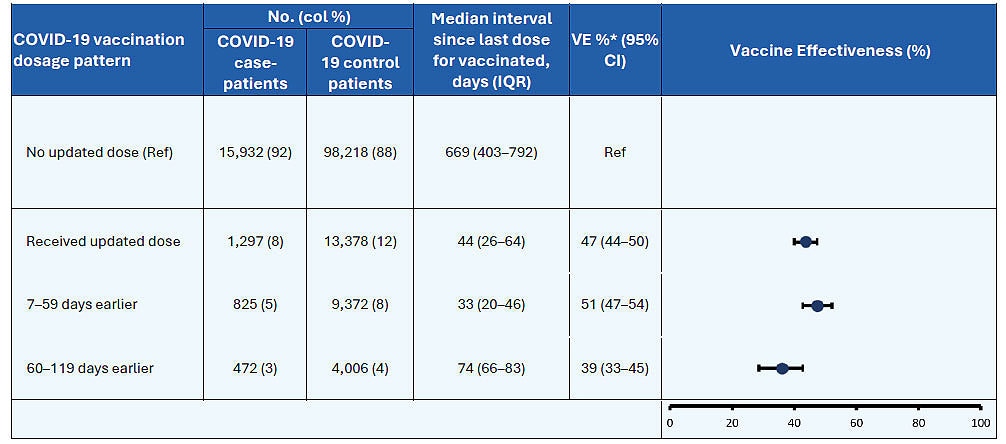

Vaccine effectiveness data provide the best real-world information on impact of COVID-19 vaccines on hospitalization. Data shown below from two studies presented at the Feb. 28–29, 2024, meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices demonstrate that the 2023–2024 COVID-19 vaccine is associated with an additional ~50% increase in protection against COVID-19-associated hospitalization.

Vaccine Effectiveness of 2023-2024 vaccine against hospitalization among immunocompetent adults aged ≥18 years

VE estimates adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity, geographic region, and calendar time. MMWR February 29, 2024

Data from another study suggest that these vaccines provide similar protection against disease caused by different co-circulating variants. Vaccines continue to provide protection to both people who have had a prior infection and those who have not. To be optimally protected against COVID-19, everyone 6 months and older should receive the latest CDC-recommended vaccine.

Infants <6 months are not eligible for COVID-19 vaccines but vaccination during pregnancy helps protect both pregnant people and their young infants from hospitalization due to COVID-19. For people with immunocompromising conditions, vaccine responses can be impaired, but vaccines provide protection against severe illness in this population. People who are moderately or severely immunocompromised are recommended to receive at least 1 dose of updated 2023–2024 COVID-19 vaccine.

Immunizations are the cornerstone of protection not just for COVID-19 but also for influenza. New in the 2023-2024 season, immunizations are available to protect those at highest risk from RSV, including older adults and infants.

Vaccines substantially reduce the risk of hospitalization, and many people at higher risk of severe disease are missing this layer of protection

| Vaccine | Real-world effectiveness against hospitalization* | % of adults vaccinated | % older adults vaccinated | % of children vaccinated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19** | Approximately 50% | 22% | 42% | 12% |

| Influenza** | Approximately 42% | 48% | 73% | 50% |

| RSV*** | Not yet available | Not approved for all adults | 22% | Not approved for all children |

*Data on COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness among adults for updated (2023-2024) COVID-19 vaccine and 2023-2024 seasonal influenza vaccine

**Data on 2023-2024 updated COVID-19 vaccines and 2023-2024 seasonal influenza vaccine from CDC’s National Immunization Survey (NIS) as of February 16, 2024. More detail, including confidence intervals around these point estimates, is available on CDC’s Respiratory Virus Data Channel. Data on percentage of older adults vaccinated for COVID-19 and influenza are for those 65+ years and for those 60+ years for RSV.

***RSV vaccination is recommended for older adults aged 60+ years based on shared clinical decision-making with a healthcare provider. RSV protection for young children is available through vaccination of pregnant people or use of an immunization called nirsevimab for young children. As of January 2024, an estimated 16% of pregnant people 32+ weeks gestation reported receiving RSV vaccine, and among females with an infant <8 months, 41% reported their infant received nirsevimab.

SARS-CoV-2 evolution, variants, and vaccines

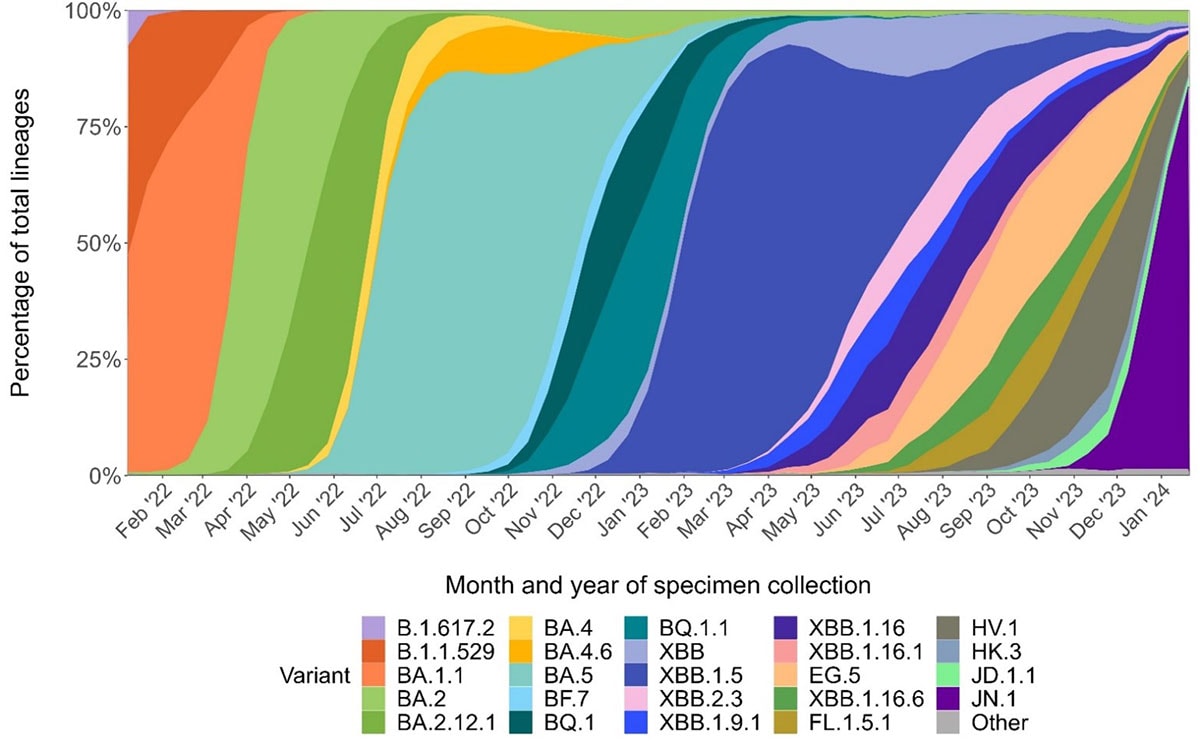

RNA viruses like influenza and SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, accumulate random mutations over time as they replicate. Out of the many mutations that happen, a small number can provide advantages that lead to new variant lineages with increased fitness (e.g., infect people more easily or be more transmissible). Early in the pandemic, circulating SARS-CoV-2 genomes were relatively stable. Because the virus was so new, our immune systems did not recognize it, and the virus did not need new mutations to escape existing immunity to continue spreading. As population immunity increased and more people developed antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, this immune pressure selected for mutations that helped the virus escape from neutralizing antibodies, generating new variants. This evolving situation led to viruses that had many changes in the virus spike protein, such as early Omicron variants (e.g., BA.1, BA.2). These ongoing changes in the spike protein, called antigenic drift, from early virus lineages like the Alpha variant to the first Omicron variants resulted in significant escape from neutralizing antibodies, allowing reinfections of people who had been infected by early variants and leading to reduced vaccine effectiveness. Currently, all SARS-CoV-2 viruses circulating are descendants of the early Omicron variants.

Changes in the spike protein that enable escape from neutralizing antibodies are the major driver of SARS-CoV-2 evolution, since they allow the virus to better escape people’s existing immunity. To better target the changing virus and increase protection against new variants, the COVID-19 vaccine is periodically updated. For example, the updated COVID-19 vaccine for 2023–2024 includes uses XBB.1.5 antigen, a variant that was dominant for much of 2023.

A wide range of SARS-CoV-2 variants have been causing infections over time, most recently dominated by JN.1, representing increased transmission or immune escape by successive variants

Figure based on CDC genomic surveillance data

In 2023, a variant called BA.2.86 emerged with many changes in the spike protein compared to other circulating variants, raising concerns that it might lead to a similar degree of immune escape as the initial Omicron variant. This variant, in the form of its offspring JN.1—just one mutation different from BA.2.86, displaced the other co-circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants, demonstrating it had higher fitness than other variants. However, vaccines continued to work well against JN.1, and the number of U.S. COVID-19-associated hospitalizations occurring at this time did not exceed that of the previous year. These findings suggest that hybrid immunity induced by the updated vaccines, provided robust cross-protection against this variant and likely a wide range of variants, although continued vigilance is critical.

SARS-CoV-2 will continue to evolve, and new variants will continue to replace previous viruses. Therefore, genomic surveillance is used to identify and track variants, and representative viruses are phenotypically characterized as part of coordinated global efforts to develop updated vaccines as needed. CDC along with partners (e.g., National Institutes of Health, Food and Drug Administration, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and World Health Organization) continue to conduct genetic surveillance to monitor for new variants, perform epidemiologic and laboratory studies to understand immune escape, and monitor key indicators like hospitalizations and emergency department visits to help inform prevention strategies. This is a continuous and iterative process that will help prepare for the upcoming 2024–2025 fall and winter season.

SARS-CoV-2 shedding and transmission dynamics

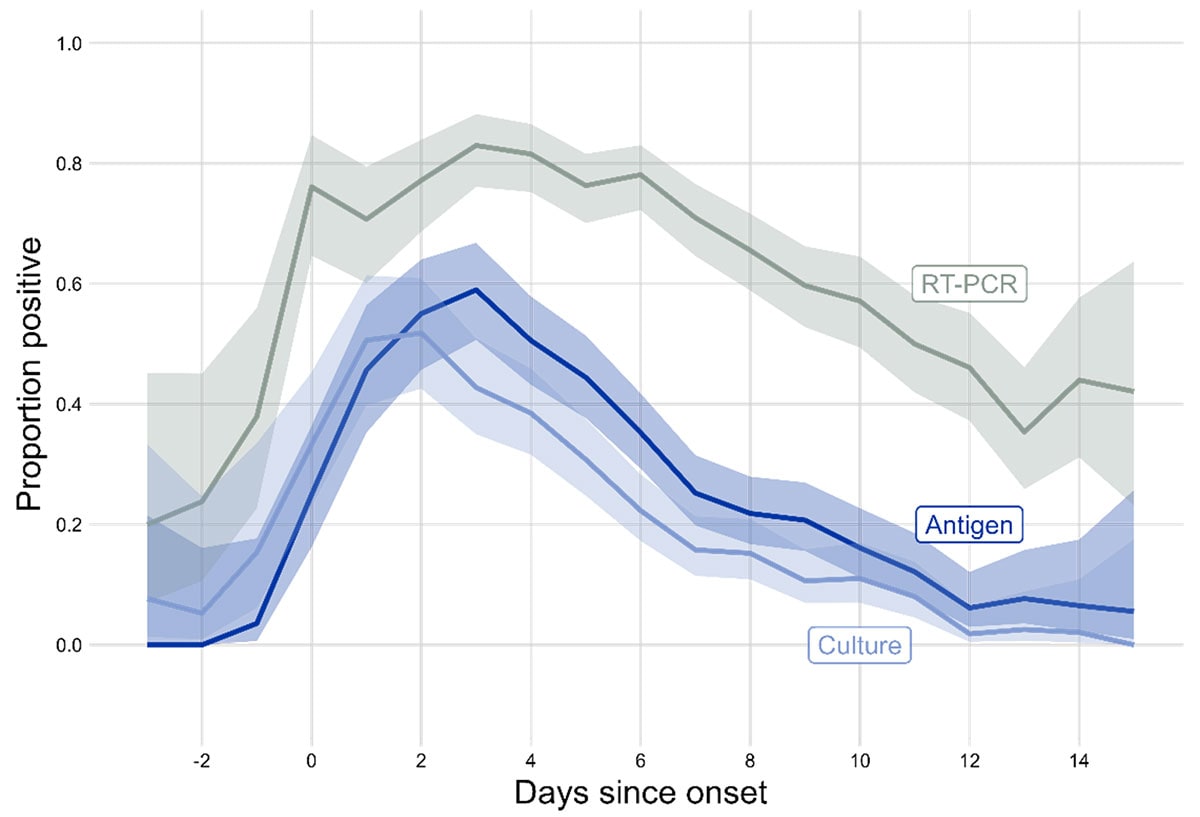

Even as the SARS-CoV-2 virus has continued to evolve, the duration of shedding infectious virus has remained relatively consistent, with most individuals no longer infectious after 8-10 days. The presence of certain COVID-19 symptoms, most prominently fever, is associated with greater infectious virus on the day of symptom. The highest levels of culturable virus typically occur within a few days before and after symptom onset. Since Omicron BA.1 variant, there is a slightly shorter time between infection to symptom onset than previous variants. Overall, these data suggest most SARS-CoV-2 transmission, regardless of variant, largely occurs early in the course of illness.

Notably, over half of SARS-CoV-2 community transmission is estimated to come from people who are asymptomatic at the time, including both pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, meaning exposure to the virus in the community from people who do not know they are infected is likely common.

Highest levels of culture-positive SARS-CoV-2, an indicator of infectiousness, occur in the days around and after symptom onset, with a small proportion of people continuing to have culturable virus beyond one week

Unpublished data from the Respiratory Virus Transmission Network, involving five U.S. sites that enrolled people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and their household contacts during November 2022–May 2023. Onset was defined as first day of symptoms or, if asymptomatic, first positive test. Note that people can have positive PCR tests, which detect viral genetic material, after they are no longer shedding infectious virus, and culture is the best indicator of infectious virus. This figure is similar to one previously published based on data from early 2021, underscoring the overall stability of viral shedding across variants.

In the Delta variant era, vaccination was associated with reduced infectious virus, demonstrating the potential impact of immunity on viral shedding and transmission. Immunity from vaccination, as well as previous infections, wanes over time, which likely attenuates this impact. Additionally, the continued evolution of variants better able to escape existing immunity may also affect the impact of vaccination and previous infection on shedding of infectious virus.

Improvements related to other prevention and control strategies

In addition to greater population understanding of effective prevention strategies like hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, cleaning, masks, and physical distancing, advancements in awareness, accessibility, and the science base related to treatment, air quality, tests, and steps to prevent spread when you’re sick have also enabled people to act to lower the risk from respiratory viruses.

Treatment

Several medications are available for outpatient treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 for people at increased risk of severe illness. Data for nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (Paxlovid), the first-line drug available for oral use, suggest that it reduce the risk of hospitalization and death by half or more. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that examined nirmatrelvir-ritonavir effectiveness and efficacy found that people who received nirmatrelvir-ritonavir had 75% lower odds of death and 60% lower odds of hospitalization. People who received nirmatrelvir-ritonavir had 83% lower odds of hospitalization and death as a composite outcome compared with people who did not use nirmatrelvir-ritonavir.

However, uptake of these treatments remains suboptimal, meaning many people are missing this layer of protection against hospitalization and death. A study of patients in the Veterans Health Administration reported that among all persons with SARS CoV-2 infection, 24% used outpatient antiviral medications in 2022, remaining at that level through early 2023. Similar overall rates of use, with a maximum of 34%, were found using observational data of a large cohort from health care systems participating in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet). This study also highlighted racial and ethnic differences in treatment uptake. During April–July 2022, treatment with nirmatrelvir-ritonavir among adults aged ≥20 years was 35.8%, 24.9%, 23.1%, and 19.4% lower among Black, multiple or other race, American Indian or Alaska native or other Pacific Islander, and Asian patients, respectively, than among white patients (31.9% treated). A CDC study found that among 699,848 U.S. adults aged ≥18 years eligible for nirmatrelvir-ritonavir during April–August 2022, 28.4% received a prescription with 5 days of being diagnosed with COVID-19.

CDC and NIH continue to monitor real-world effectiveness data for COVID-19 treatment. Current evidence suggests that effectiveness of nirmatrelvir-ritonavir is retained among persons who have been vaccinated and confers incremental benefit among persons at high risk for severe disease, although this is an underutilized treatment.

Air quality

Ventilation and related strategies to improve indoor air quality can reduce infective viral particle concentrations in indoor air. In 2023, informed by accumulating evidence, CDC issued recommendations for using Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) 13 or greater and getting at least 5 air changes per hour of clean air in occupied spaces through air flow, filtration, or air treatment. CDC’s Interactive Home Ventilation Tool can help people identify strategies they can use to decrease the level of viral particles in their home. CDC also now provides a similar tool for building owners and operators. In addition, the U.S. Government issued a Clean Air in Buildings Challenge to help building owners and operators improve indoor air quality and protect public health.

Tests

Laboratory tests are currently widely available and can be readily accessed for diagnosis of COVID-19, influenza, and RSV. At-home antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2 are also widely available and increasingly familiar to the public. At-home rapid tests for influenza have recently received FDA approval and may become more widely accessible over time.

Staying home when sick and other steps to prevent spread

The importance of staying home and away from others when sick became more widely understood during the COVID-19 pandemic. When individuals have the option to stay home and be compensated while sick, they are much more likely to do so. Similarly, people with prior telework experience are more apt to work from home when they have respiratory symptoms, rather than work in person at an office.

Unified, practical guidance

Unlike early in the pandemic when COVID-19 was nearly the only respiratory virus causing illness, it is now one of many, including influenza, RSV, adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, enteroviruses, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, and other common human coronaviruses. CDC is focusing guidance on the core measures that provide the most protection across respiratory viruses. The updated guidance emphasizes the importance of staying home and away from others when sick from respiratory viruses, regardless of the virus, as well as additional preventive actions.

Virus not known in most respiratory infections

Viruses cause most acute respiratory illnesses, but it is rarely possible to determine the type of virus without testing, and oftentimes testing does not change clinical management. Testing for most respiratory pathogens is rarely available outside of healthcare settings. Although at-home antigen testing is widely available for COVID-19, most infections likely go undiagnosed. In a recent CDC survey, less than half of people said they would do an at-home test for COVID-19 if they had cold or cough symptoms, and less than 10% said they would get tested at a pharmacy or by a healthcare provider.

Even when testing occurs, COVID-19 is often not identified early in illness. The overall sensitivity of COVID-19 antigen tests is relatively low and even lower in individuals with only mild symptoms. Significant numbers of false negative test results occur early in an infection. This means mildly symptomatic cases are not always detected, and when they are detected, it often occurs several days into an illness, which is typically past when peak infectiousness occurs.

Public interest in prevention is not limited to COVID-19

A November 2023 survey from the Harvard Opinion Research Program found people were not meaningfully more concerned about any one respiratory virus, with roughly similar proportions reporting being concerned about getting infected with COVID-19, seasonal influenza, RSV, and a cold. Relatedly, a CDC survey found that a majority of Americans take precautions when sick with cold or cough symptoms (i.e., avoiding contact with people at higher risk, avoiding large indoor gatherings) even if they don’t know what virus is causing the illness.

Respiratory Virus Guidance does not imply all viruses are the same

Respiratory viruses are certainly not all the same. Some, like SARS-CoV-2, spread more through respiratory particles in the air, whereas others, like RSV and adenovirus, are thought to also spread via surface transmission. As such, this guidance is not meant to apply to specialized situations, like healthcare or certain disease outbreaks, in which more detailed guidance specific to the pathogen may be warranted. For example, adenoviruses are resistant to many common disinfectants and can remain infectious for hours on environmental surfaces. For the general public, however, an overall focus on hygiene, indoor air improvements, and mask use, coupled with necessarily specific recommendations about vaccines and treatment, provides a practical approach that addresses the key prevention measures.

Updated guidance on steps to prevent spread when you are sick is informed by numerous factors

The updated Respiratory Virus Guidance recommends people with respiratory virus symptoms that are not better explained by another cause stay home and away from others until at least 24 hours after both resolution of fever AND overall symptom are getting better. This recommendation addresses the period of greatest infectiousness and highest viral load for most people, which is typically in the first few days of illness and when symptoms, including fever, are worst. This is similar to longstanding recommendations for other respiratory illnesses, including influenza.

A residual risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission remains, depending on the person and circumstances, after the period in which people are recommended to stay home and away from others. Five additional days of interventions (i.e., masking, testing, distancing, improved air quality, hygiene, and/or testing) reduce harm during later stages of illness, especially to protect people at higher risk of severe illness. Some people, especially people with weakened immune systems, might be able to infect others for an even longer time. It is important to note that a similar residual risk of transmission is also true for influenza and other viruses.

In addition to the overall reduction in risk from COVID-19, other factors considered in developing this component of the guidance included assessment of personal and societal costs of extended isolation (e.g., limited paid sick time), analysis of the period of peak infectiousness ( see section 4.), and acknowledgement that many people with respiratory virus symptoms do not often know the pathogen that is causing their illness.

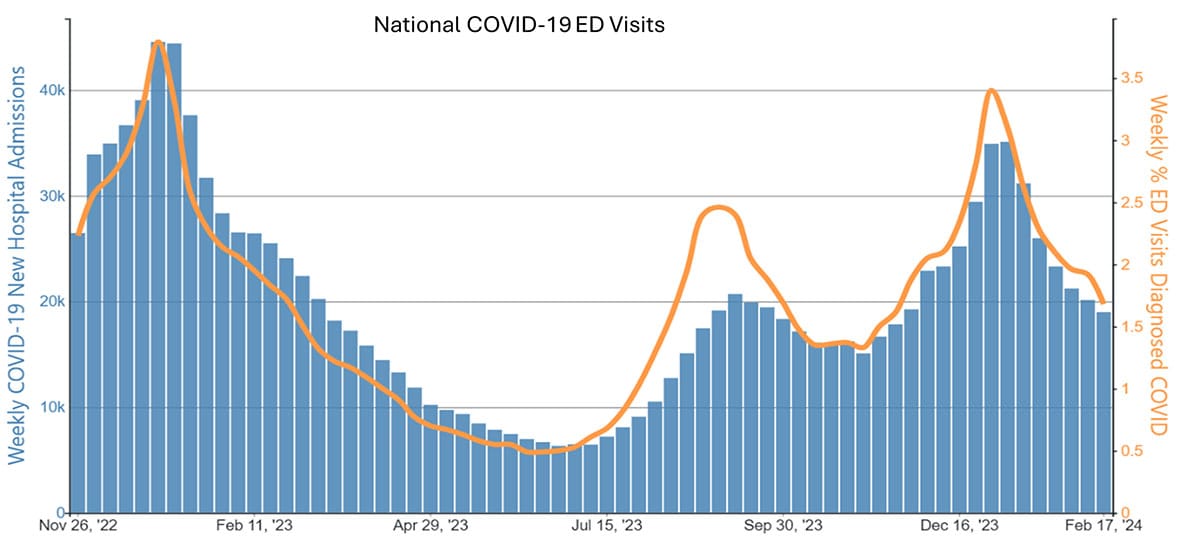

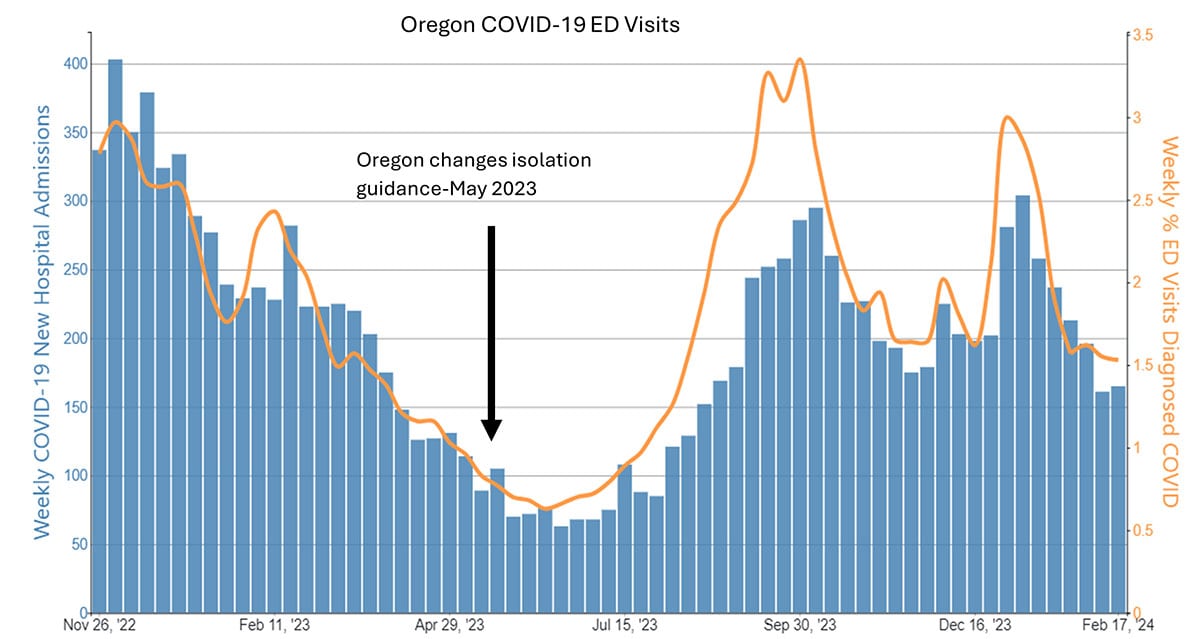

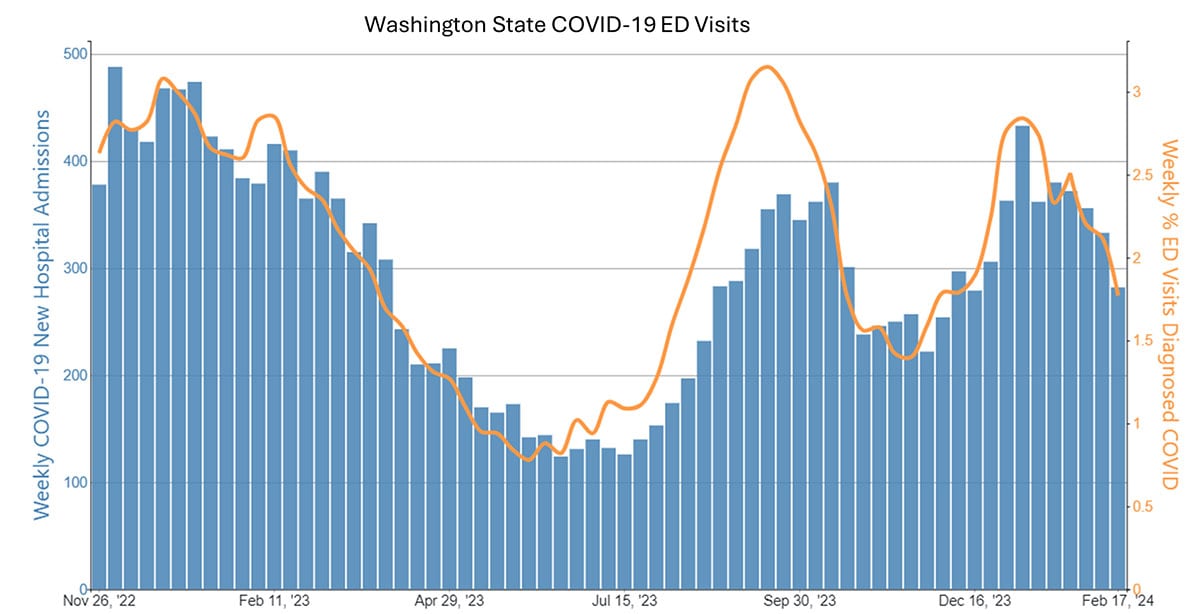

Case examples from states and countries that changed their COVID-19 isolation guidance to recommendations similar to CDC’s updated guidance did not experience clear increases in community transmission or hospitalization rates. Examples include the most populous Canadian provinces (Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia), Australia, Denmark, France, and Norway, as well as California (on January 9, 2024) and Oregon (May 2023). In California and Oregon, for the week ending February 10, COVID-19 test positivity, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations were lower than the national average.

No appreciable difference in COVID-19 ED and hospitalization trends in Oregon vs. nation or neighboring Washington after guidance change

Data from CDC’s COVID Data Tracker

Ongoing vigilance and action

Need for ongoing implementation of recommendations

Vaccines remain an underused layer of protection, even for groups at higher risk. For example, only 42% of adults aged 65 years or greater had received an updated COVID-19 vaccine as of February 16, 2024, compared with 73% for flu. COVID-19 antiviral treatments are also substantially underused to prevent severe COVID-19, meaning many people are missing out on important protection. Influenza treatment is also underused.

Ongoing data monitoring

The SARS-CoV-2 virus will continue to evolve, and new variants will continue to replace previous viruses. Genomic surveillance to monitor for new variants, epidemiologic studies to understand immune escape, infectiousness, severity, and monitoring of key indicators like hospitalizations and emergency department visits, all help inform prevention strategies.

Various data systems are in place to continue to monitor for changes in how COVID-19 affects us. These include monitoring laboratory-based percent positivity and wastewater as indicators of changes in infections. Data on hospitalizations and deaths are indicators of severe illness while data on hospital occupancy and capacity provide information on stress on the healthcare system. Epidemiologic studies continue to assess how infectious the virus is and how efficiently it transmits between people as well as the severity of disease it causes. Ongoing monitoring through genomic surveillance and viral characterization will continue to be important to identify and describe new SARS-CoV-2 variants that may emerge. Vaccines will continue to be updated based on circulating variants, and other protective measures can be scaled up as needed. If variants emerge that have significant immune escape from existing vaccines and therapeutics, non-pharmaceutical interventions such as masking, distancing, and ventilation will be particularly important.

Conclusion

COVID-19 remains an important public health threat, but it is no longer the emergency that it once was, and its health impacts increasingly resemble those of other respiratory viral illnesses, including influenza and RSV.

Protective tools, like vaccination and treatment that decrease risks of COVID-19 disease are now widely available and resultantly, far fewer people are getting seriously ill from COVID-19. Complications like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and Long COVID are now less common as well. Data indicate rates of hospitalizations and deaths are down substantially, and that clinically COVID-19 has become similar to, or even less severe in hospitalized people, than influenza and RSV.

These factors have enabled CDC to issue updated Respiratory Virus Guidance that provides the public with recommendations and information about effective steps and strategies tailored to the current level of risk posed by COVID-19 and other common respiratory viral illnesses.