CDC reports increase in birth defects potentially related to Zika in US areas with local transmission

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a report on birth defects potentially related to Zika among babies born in 2016. This article, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), is the first to report a population-level increase in the birth defects most strongly linked to Zika virus infection during pregnancy in areas with local transmission in the United States. There were almost 1 million live births in 2016 in the 15 states and territories included in the analysis.

Main Findings

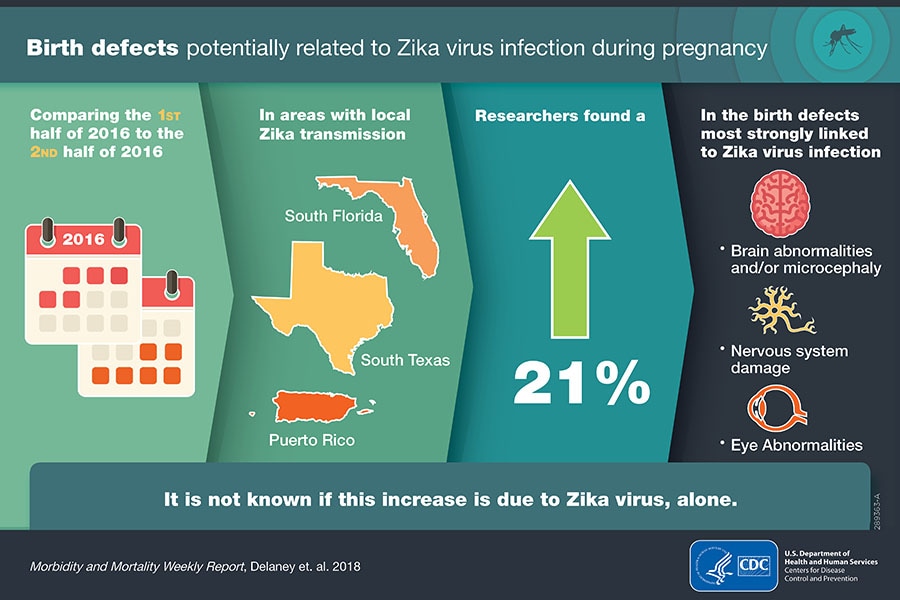

Using information from birth records, CDC researchers found that from July to December 2016, areas with local transmission, which included South Florida, South Texas, and Puerto Rico, had a 21% increase in the number of babies born with the birth defects most closely linked to Zika compared to January through June 2016.

It is not known if local transmission of Zika virus, alone, is the cause of the increase in selected birth defects in the second half of 2016.

Among births in all states included in the analysis, CDC researchers found about 3 out of every 1,000 babies born had a birth defect caused by Zika or other factors. Among these babies,

- About half (49%) were born with brain abnormalities and/or microcephaly (small head size),

- 2 in 10 (20%) had neural tube defects and other early brain abnormalities,

- 1 in 10 (9%) had eye abnormalities without brain abnormalities, and

- Over 2 in 10 (22%) had nervous system damage, including joint problems and deafness, without brain or eye abnormalities.

The majority (95%) of these infants with birth defects potentially related to Zika were born to mothers that were not tested for Zika or did not have Zika test results available. These women likely did not receive testing because they did not have symptoms of Zika or were not recognized as potentially exposed to Zika.

Researchers expect this increase in Zika-related birth defects will continue and might increase since many pregnant women exposed to Zika virus in late 2016 gave birth in 2017.

About This Study

CDC’s US Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry and Zika Birth Defects Surveillance are innovative tracking systems that collect enhanced medical information to better understand Zika virus infection in pregnant women and their babies. Data from these systems answer important questions by tracking Zika virus infection in two different ways.

- US Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry: tracks pregnant women with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection and their infants.

- Zika Birth Defects Surveillance: tracks any infant with a birth defect potentially related to Zika virus infection, regardless of Zika lab testing or exposure.

Zika Birth Defects Surveillance finds infants with birth defects by using a standard case definition that allows health departments across the country to collect infants’ medical information in a systematic and comparable way. Since Zika Birth Defects Surveillance does not require a mother to have Zika laboratory testing, the system finds infants with birth defects that the US Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry might have missed because the mothers did not have Zika symptoms. Identifying these birth defects early helps these families have access to services and support for the best care for their infants.

Innovative Public Health Tracking

These systems, made possible through collaborations with state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments, are essential for identifying and helping mothers and babies affected by Zika virus. Together, they highlight successful collaboration across different areas of public health including birth defects, infectious disease, maternal and child health, vital statistics, and public health laboratories to quickly identify mothers and infants affected by Zika.

This public health innovation and collaboration continues to increase our understanding of Zika, and demonstrates how this system could be enhanced to combat other threats to mothers and babies for the common defense of the country.

Reference

Delaney A, Mai C, Smoots A, et al. Population-Based Surveillance of Birth Defects Potentially Related to Zika Virus Infection — 15 States and U.S. Territories, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:91–96. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6703a2