Stories from the Field on Zika and Pregnancy

During the response to the Zika virus outbreak, CDC collaborated with state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments to protect mothers and babies from Zika virus infection. These stories show what jurisdictions did at a local level to fight Zika.

California Birth Defects Monitoring Program

In 2016, using funding from CDC’s Zika Birth Defects Surveillance program, the California Birth Defects Monitoring Program (CBDMP) expanded its coverage to include an additional nine counties, specifically those most affected by Zika virus infections. Because Zika virus is an infectious disease that can cause birth defects, CBDMP also added two coordinators to make sure information was easily exchanged between the state’s infectious disease programs and CBDMP. This way, once a pregnant person with Zika virus infection was identified, the public health department could work to ensure both her and her child’s needs were met quickly. When Zika-associated birth defects were first reported, CBDMP’s infrastructure and CDC Zika funding enabled it to rapidly respond to birth defects surveillance needs across the state. Today, the program covers approximately 82 percent of California’s annual births and fetal deaths.

Massachusetts Department of Health

Massachusetts was the first state to report Zika data to CDC’s US Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry (USZPIR). The state’s Birth Defects and Infectious Disease teams were already collecting case information through two standalone systems. However, as the risk of Zika-related congenital defects in babies began to emerge, the need for both groups to share information and access all relevant data in one place became critical, resulting in the integration of the two systems by May 2017. Funding from CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD) allowed the state to implement rapid population-based surveillance of birth defects potentially related to Zika. “We had a strong foundation but getting additional resources allowed us to leverage and improve our capacity to respond to Zika and collaborate with each other in a very integrated way,” says Catherine Brown, state epidemiologist and state public health veterinarian.

Mississippi State Health Department

In 2016, one of the priorities for the Mississippi State Department of Health was raising awareness and building capacity to confront the threat of Zika. “One of the strategies the Birth Defects program initiated when we received Zika funding was to make sure we addressed multiple racial and ethnic groups,” says Alyce Stewart, director of Mississippi’s Bureau of Genetic Services. Since April 2017, community health directors and public health educators have conducted outreach activities in the community at schools and universities, churches, health professional meetings, and health summits. The state has also provided educational materials and Zika coloring books to school-aged children. But the best aspect of the Zika response, emphasizes Stewart, is the collaboration that has resulted across the health department. “We were working in silos but were able to get to the table, talk, and establish a foundation to fight Zika.”

New York City Zika Response Team

Confronted with the challenge of identifying and testing a large number of pregnant people at risk for Zika, New York City’s (NYC’s) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) used city and federal funding to help support a team of more than 10 staff to work on surveillance activities for CDC’s US Zika Pregnancy and Infant Registry (USZPIR). The NYC Zika Pregnancy Registry (ZPR) surveillance team implemented comprehensive outreach to healthcare providers throughout the city and improved surveillance capacity to ensure that pregnant people at risk for Zika received necessary evaluation and testing. The team engaged in outreach to health providers about the importance of Zika testing and following recommended evaluations through citywide conference calls, health alert emails, grand rounds, and other in-person presentations for facilities and hospital networks. To ensure it could follow the infants over time, the team also connected with the citywide immunization registry and regional health information networks to identify where infants are seeking care.

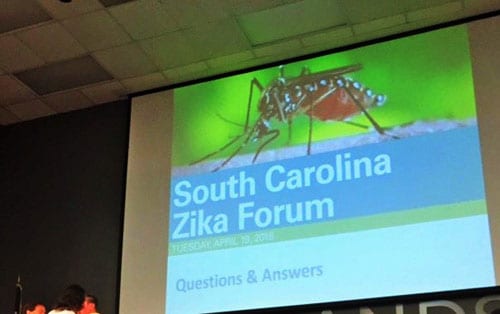

South Carolina Department of Health & Environmental Control

With CDC funding, South Carolina hired its first full-time birth defects epidemiologist and additional staff to collect data. The state has collected data on birth defects associated with Zika since mid-2016 and has since expanded to all birth defects recommended for surveillance by CDC. “The potential for local transmission of Zika virus created a need for the SC Birth Defects Program to establish a baseline for birth defects associated with Zika. This has been a challenge because there are many Zika-associated conditions we did not collect information on prior to the Zika outbreak in the Americas,” says Vinita Leedom, of the South Carolina Birth Defects Program. South Carolina’s Birth Defects program plans to continue enhanced surveillance as CDC funding allows and share findings with partners. Leedom says the program also plans to refer all infants with birth defects to early intervention “so families may more directly benefit from our surveillance system.”

Tennessee Department of Health

Tennessee identified its first case of travel-associated Zika virus infection in August 2016. The state hired a new Zika Pregnancy Registry Coordinator, and the birth defects team made it a priority to reach out to local health departments, providers, and birthing facilities statewide. “We rely on local and regional health departments to send patient information up to us,” explains Tori Ponson, Tennessee’s Zika Pregnancy Registry Coordinator, Zika-related Birth Defects Surveillance System manager, and Birth Defects Epidemiologist, noting that strong communication channels between the local and regional offices and TDH are key in addressing public health challenges like Zika. Ponson says he is most proud of the communication with local hospitals that are now working with the state toward a common goal. “We’ve also done well building relationships within our own health department, improving existing communications and establishing some that weren’t there before.”