Syrian Refugee Health Profile

Priority Health Conditions

A list of priority health conditions to consider when caring for or assisting Syrian refugees.

Background

Geography, Ethnic Groups, Language, Education and Literacy, Family and Kinship, Religious Beliefs, Tips for Clinicians

Population Movements and Refugee Services in Asylum Countries

From Syria, To the United States

Healthcare Access and Health Concerns

Primary Healthcare, Immunizations, Reproductive Health, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, Gender-Based Violence, Early and Forced Marriage, Mental Health

Medical Screening of US-Bound

Visa Medical Examination, Pre-Departure Medical Screening, Pre-Embarkation Checks, Surveillance, Vaccination Program, Presumptive Therapies for Intestinal Parasites, Post-Arrival Medical Screening

Health Information

Communicable Diseases, Parasitic Infections, Non-Communicable Diseases, Mental Health

Priority Health Conditions

The following health conditions are considered priority conditions that constitute a distinct health burden for the Syrian refugee population:

Background

The Syrian conflict, which began in 2011, has resulted in the largest refugee crisis since World War II, with millions of Syrian refugees fleeing to neighboring countries including Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey 1. Syrian refugees have also fled to Europe, with many crossing the Mediterranean Sea in order to reach European Union-member nations, mainly Greece, then traveling north to countries such as Germany and Sweden. Syria’s pre-war population of 22 million people has been reduced to approximately 17 million, with an estimated 5 million having fled the country 2, 3, and more than 6.5 million displaced within Syria 4. As fighting has continued across the country, an increasing number of health facilities have been heavily damaged or destroyed by attacks, leaving thousands of Syrians without access to urgent and essential healthcare services 5.

Geography

The Syrian Arab Republic (Syria) is located in the Middle East, bordering Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Israel; it is also bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the west (Figure 1). Syria is largely a semiarid or arid plateau, and encompasses various mountain ranges, desert regions, and the Euphrates River Basin 6.

Figure 1: Map of Middle East

Ethnic Groups

Approximately 90% of Syrians are of Arab descent 7,. The largest ethnic minority in Syria is Kurdish, which constitutes roughly 9% of the total population. Kurds primarily reside in northern and northeastern Syria. Kurds have faced marginalization and persecution both in Syria and throughout the Middle East, where they are the fourth largest ethnic group, with sizable populations in Iraq, Iran, and Turkey 8. The remaining 1% of the Syrian population is of Armenian, Circassian, and Turkoman descent 6, 7.

Language

Arabic, the official language of Syria, is spoken by approximately 90% of Syrians. Most Syrians speak colloquial Arabic, and read and write Modern Standard Arabic 9. Circassian, Kurdish, Armenian, Aramaic, Syriac, French, and English are also spoken. French and English are widely understood, particularly among educated groups in urban areas 6. While many Syrian refugees have a basic knowledge of English, relatively few are proficient 9.

Education and Literacy

Prior to the conflict, Syria had one of the strongest education programs in the Middle East, with 97% of primary-school-age children attending school 10. The collapse of the Syrian education system is most notable in areas of intense violence. Less than half of all children in Al-Raqqa, Idlib, Aleppo, Deir Ezzor, Hama, and Daraa currently attend school. School attendance in Idlib and Aleppo has plunged below 30% 10. An estimated 500,000 to 600,000 Syrian refugee children in the Middle East and North Africa currently have no access to formal education 10. However, it is likely that the number of children with no access to learning is considerably higher, as these figures only account for registered refugees 10.

Overall literacy in Syria is estimated at 86.4% 7. Youth literacy is estimated at 95.9 percent 2. Men tend to have higher literacy rates than women (91.7 versus 81% percent) 7.

Family and Kinship

The typical Syrian family is large and extended. Families are close-knit, and protecting the family’s honor and reputation is important. Like many Arab societies, Syrian society is patriarchal. Women are believed to require protection, particularly from the unwanted attention of men. Generally, an elderly male has ultimate decision-making authority and is seen as the family protector 9.

Women, especially from religiously conservative families, are typically responsible for cooking, cleaning, and caring for children, while men are typically responsible for supporting the family financially. Among the upper classes, women are well-educated and often work outside the home. However, women from middle-class urban and rural households are expected to stay home and care for children, while women from poor families often work in menial, low-wage jobs 9.

Religious Beliefs

Islam is practiced by 90% of the population. Approximately 74% of the total population are Sunni and 16% are Shia (namely Alawite and Ismaili) 9. Minority religious groups include Arab Christians (Greek Orthodox and Catholic), Syriac Christians (also known as Chaldeans), Aramaic-speaking Christians, and Armenian Orthodox and Catholics 9. These minority groups account for 10% of the population. There is also a small Kurdish-speaking Yazidi community 9.

Tips for Clinicians

Syrians are familiar with and tend to engage with the Western medical model. Syrians often seek immediate medical care for physical injury or illness, are anxious to begin treatment, and will generally listen to their physician’s advice and instructions. They tend to see physicians as the decision makers, and may have less confidence in non-physician health professionals. Although most Syrians are familiar with Western medical practices, like most populations, they tend to have certain care preferences, attitudes, and expectations driven by cultural norms, particularly religious beliefs, and expectations 9. While many Syrians may have similar preferences due to shared cultural norms and past experiences, it is important to recognize that individuals in this population may have diverse preferences, attitudes, and expectations toward healthcare.

For example, Syrian patients or their families might be more likely than the general U.S. patient population to:

- Prefer a provider of the same gender 9, 11

- Request long hospital gowns for modesty (especially female patients) 9, 11

- Request meals in accordance with Islamic dietary restrictions (Halal) during hospital stays or request family to bring specific meals or foods 9, 11

- Fast or refuse certain medical practices (e.g., to take oral medication) during certain periods of religious observance such as the month of Ramadan 9

- Be less likely to consider conditions chronic in nature (they may cease taking medications if symptoms resolve and less likely to return for follow-up appointments if not experiencing symptoms) 9

- Not be open to questions or discussions regarding certain sensitive issues—particularly those pertaining to sex, sexual problems, or sexually transmitted infections 9

- Refuse consent for organ donation or autopsy 11

When possible, providers should attempt to provide refugee patients with translators who are of the same ethnic background. In certain circumstances, gender concordance with translators may be of importance for some patients.

Additional Resources

For more information about the orientation, resettlement, and adjustment of Syrian refugees visit the Cultural Orientation Resource Center.

Population Movements

From Syria

By December 2015, the conflict in Syria had produced nearly 5 million registered Syrian refugees 12. However, this figure only accounts for refugees who have been registered with UNHCR. The number of unregistered refugees throughout the Middle East will likely increase, as refugee camps have become overcrowded as the number of Syrian refugees grows. Syrian refugees are entering various countries to flee ongoing violence in their home country. Depending on the country of asylum, services available to Syrian refugees may vary and are likely to change substantially over time. Table 1 shows the estimated number of Syrian refugees in major countries of asylum, and discusses the living conditions and health services available to Syrian refugees in various countries. These estimates are based on UNHCR referrals for resettlement.

Table 1. Syrian refugee arrivals, living conditions, and access to health services by country of asylum

| Country of Asylum | Syrian Arrivals* | Living Conditions | Access to Health Services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | 227,971 | 38% camp 62% non-camp 13 |

Specific services offered to select registered refugee populations 14, 15, 16. |

| Jordan | 655,833 | 82% urban or informal settlements 13 | Syrian refugees (registered with UNHCR) can access the public health system 17. |

| Lebanon | 1,017,433 | Urban areas (Beirut); Informal tent camps (Bekaa Valley); Sabra and Shatila camps (Beirut) 18 | UNHCR registration is required for Syrian refugees to access primary healthcare services 17. Registration of new arrivals was halted in May 2015 per the request of the Lebanese government 12. |

| Turkey | 2,764,500 | Districts (known as a satellite cities); Camps along Turkish-Syrian border 19 | Registered Syrian refugees, living in satellite cities, are enrolled in the Turkish General Health Insurance Program and are able to access free health services. In camps, nongovernmental organizations provide clean water, sanitation, and other health services 19. |

| Egypt | 115,204 | Urban 20 | Syrian are granted access to the public health system, but are required to pay the same fees as Egyptians 17. Services are overburdened and often inaccessible due to cost 20. |

*Number of UNHCR-registered refugee arrivals as of October 31, 2016

To the United States

Historical Migration

Syrians began arriving in the United States as immigrants in the late 1800s. The first wave of immigration from the Middle East and North Africa continued into the mid-1920s. This initial wave of immigrants consisted largely of Arab Christians from the Ottoman Empire and the Province of Syria, now modern-day Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Syria 21. From 1899-1932, 106,391 Syrians immigrated to the United States 22. A second wave of Syrian immigration began in 1948 and continued through 1965. According to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, more than 310,000 Arabs entered the United States from 1948-1985, of which, 60% were Muslim 22.

Recent Migration

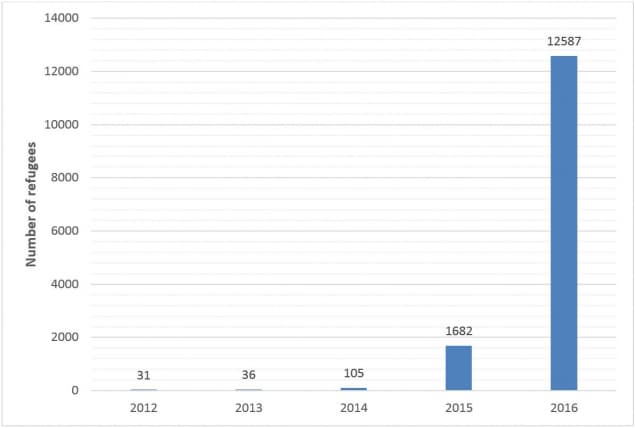

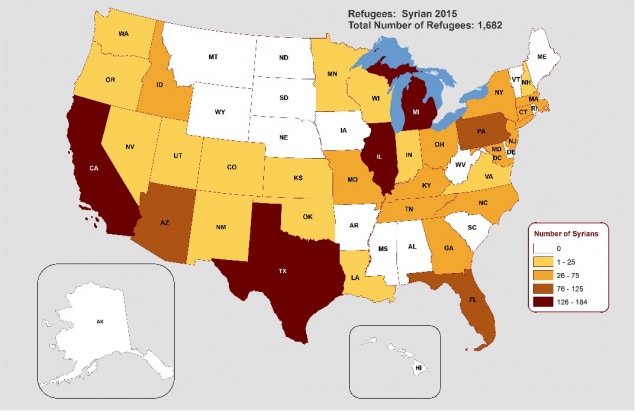

Prior to 2014, the United States Refugee Admissions Program formally resettled few Syrian refugees. From 2008-2013, the United States resettled less than 50 Syrian refugees each fiscal year Figure 3. In 2015, only 1,682 Syrian refugees resettled to the United States (Figure 4) 21. Between October 2015 and July 2016, more than 7,500 Syrian refugees have been resettled to the United States, with the largest numbers arriving in Michigan, California, Arizona, and Texas.

Figure 2: Syrian Refugee Arrivals in the United States, Fiscal Years 2012-2016 (N=14,441)

Figure 3: States of Primary Resettlement for Syrian Refugees, FY 2015 (N=1,682)

| States* | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | 184 | 10.9 |

| California | 179 | 10.6 |

| Michigan | 179 | 10.6 |

| Illinois | 134 | 8.0 |

| Arizona | 125 | 7.4 |

| Pennsylvania | 111 | 6.6 |

| Florida | 98 | 5.8 |

| New Jersey | 73 | 4.3 |

| Massachusetts | 70 | 4.2 |

| Kentucky | 61 | 3.6 |

| Georgia | 53 | 3.2 |

Healthcare Access and Health Concerns

Prior to the Syrian Civil War, Syria was classified as a lower-middle income nation, with a fairly stable middle class that had a relatively high socioeconomic status 2. As a result, the health conditions observed in this population include chronic conditions less often associated with newly arrived refugees (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, and cancer). In addition, acute illnesses and infectious diseases reflect the challenges associated with displacement, crowding, and poor sanitation.

Primary Healthcare

Access to healthcare varies greatly depending on country of asylum and whether a refugee lives in a refugee camp or in an urban or informal settlement. UNCHR reported that the majority (72.1%) of primary healthcare visits in Zaatari camp (Jordan) were due to communicable diseases. Non-communicable diseases (21.8%), injuries (4.8%), and mental illness (1.3%) were also noted as reasons for seeking primary care. Similarly, the majority of primary healthcare visits in Iraq and Lebanon were due to communicable diseases. Notably, primary healthcare visits attributed to non-communicable diseases accounted for just 7.4% and 8.3% of all primary healthcare visits in Iraq and Lebanon, respectively 13.

Immunizations

Some Syrians may have received vaccinations prior to displacement, through the Syrian national immunization program; others may have received some immunizations from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) operating in refugee settlements or camps. Additionally, U.S.-bound Syrian refugees may be receiving select vaccines as part of the Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees, depending on the country of processing (see section ‘Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees’ for additional information). However, Syrian refugees generally have not completed the full ACIP-recommended vaccination schedule prior to departure for the United States.

Women’s Health Issues

Reproductive Health

A recent study assessing the health status of women presenting to six regional primary healthcare clinics in Lebanon found that 65.5% (N=452) of women between 18 and 45 years of age were not using any form of birth control. Within this group, the mean age at first pregnancy was 19 years. Additionally, 16.4% were pregnant during the current conflict. Of note, 51.6% of all women surveyed reported dysmenorrhea or severe pelvic pain, 27.4% were diagnosed with anemia, 12.2% with hypertension, and 3.1% with diabetes 23.

Family planning services are available through the Jordanian healthcare system; however, such services are only provided to married couples 24. Birth control and family planning services are available in the Zaatari Refugee Camp, where many Syrian refugees reside. However, studies indicate that only 1 in 3 women of reproductive age are aware of birth control options in the camp 24. A survey of Syrian households in Jordan found that most women (82.2%) received antenatal care, with an average of 6.2 visits during pregnancy 25. Furthermore, 82.2% delivered their infants in a hospital, with 51.8% of births taking place in public hospitals and 30.4% in private hospitals 25.

Decisions regarding contraception and family planning are often made by the man and woman together. When offering birth control education, healthcare providers should consider providing contraception counseling to individual women and, with their consent, including male partners in these discussions 26.

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C)

Little published research has documented the prevalence and distribution of FGM/C in the Middle East. However, anecdotal and circumstantial evidence suggests that FGM/C exists throughout the region, including Syria and other Arab countries 27. The extent to which FGM/C is practiced in Syria is unknown. FGM/C has been documented in countries where Syrian refugees are seeking asylum, including Egypt, where more than 90% of girls and women between 15 and 49 years of age are reported to have undergone FGM/C 28.

FGM/C is a cultural or social custom, and is not considered a religious practice. Communities that practice FGM/C often do so with the conviction that FGM/C will ensure a girl’s proper upbringing, preserve family honor, and make a girl suitable for marriage 29. FGM/C exists in numerous countries with large Muslim populations, FGM/C is carried out by followers of various religions and sects. FGM/C has been legitimized by certain radical Islamic clerics; however, there is no basis for FGM/C in the Quran or any other religious text 27.

Gender-Based Violence

Sexual violence is a concern for women and girls in Syria, as well as in countries of first asylum. Fear of sexual violence perpetrated by other refugees or by host country nationals may cause Syrian refugee women to stay home and only venture outside when accompanied by family members 9. A recent study found that 30.8% (N=452) of surveyed Syrian refugee women reported experiencing conflict-related violence, with 3.1% of surveyed women reporting non-partner sexual violence 23.

Early and Forced Marriage

Early and forced marriage is a growing problem for young Syrian girls. Many international groups (the International Center for Research on Women, Amnesty International, the United Nations, and many others) and governments worldwide view child marriage as a human rights violation due to the child’s inability to consent to the marriage. Instances of child and forced marriages have been reported among Syrian refugees in Erbil (Iraq), Lebanon, Egypt, and Turkey 30. Some Syrian refugee families believe that child marriage is the best way to protect their daughters from the threat of sexual violence in refugee camps or urban slums, and is a means to alleviate poverty 30. As a result of early or forced marriage, girls are denied education, are unable to take advantage of economic opportunities, and are left at increased risk for early pregnancy and resulting maternal mortality, stillbirth, and other obstetric complications, as well as gender-based violence 30, 31.

Mental Health

Historically, mental illness has been stigmatized in the Syrian community. Syrians may be reluctant to acknowledge mental health issues, as such issues may be viewed as personal flaws and might bring shame upon family and friends. As a result, individuals are often reluctant to seek professional psychological or psychiatric care. However, with the recent increase in psychological trauma related to war and displacement, some Syrian refugees have become more open and accepting of mental health conditions and treatment 9.

The availability of mental health services for refugees overseas is limited. The quality of services is often poor, largely due to overstretched capacity and a shortage of trained mental health providers 32. However, mental health providers in the Middle East have seen an increase in the number of Syrians with severe mental health disorders. The largest psychiatric hospital in Lebanon has observed an increase in admissions of Syrians with severe psychopathology and suicidality since the conflict began 33, 34. Additionally, the International Medical Corps (IMC) has treated more than 6,000 Syrians, 700 (11.7%) of which had psychotic disorders, in outpatient facilities 34, 35.

Medical Screening of US-Bound Refugees

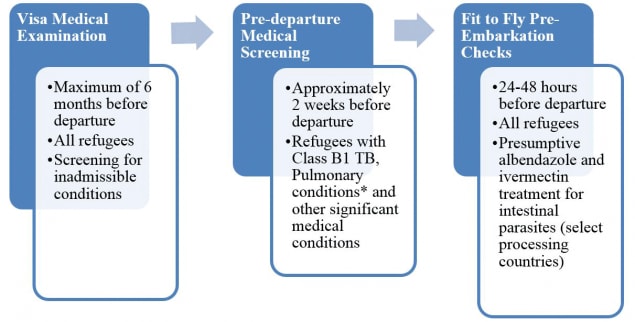

Syrian refugees who have been identified for resettlement to the United States receive a required medical examination. Depending on the country of processing, refugees may receive additional pre-departure and pre-embarkation checks (Figure 4). As outlined below, the full required medical examination occurs 3-6 months prior to departure; the pre-departure medical screening and pre-embarkation checks, if conducted, occur close to or immediately before departure for the United States.

Figure 4: Medical assessment of U.S.-bound refugees

Visa Medical Examination

As overseas medical examination is mandatory for all refugees coming to the United States and must be performed according to the CDC’s Technical Instructions. The purpose of this medical examination is to identify applicants with inadmissible health-related conditions. These include, but are not limited to, mental health disorders with harmful behavior, substance abuse, and specific sexually transmitted infections (untreated). Active tuberculosis (TB) disease (untreated or incompletely treated) is an inadmissible condition of great concern due to its infectious potential and public health implications. Technical Instructions for Tuberculosis Screening and Treatment are available on CDC’s website.

The required medical examinations for refugees processed in Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt are conducted by physicians from the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In other countries, including Lebanon, Turkey, and Austria, examinations are performed by local panel physicians appointed by the U.S. Embassy. CDC provides the technical oversight and training for all panel physicians. All panel physicians, regardless of affiliation, are required to follow the same Technical Instructions developed by CDC.

Information collected during the refugee visa medical examination is reported to CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN) and is sent to U.S. state health departments where the refugees are resettled.

Pre-Departure Medical Screening (PDMS)

Depending on the country of processing, pre-departure medical screening is conducted approximately 2 weeks before departure for the United States for refugees previously diagnosed with a Class B1 TB, pulmonary condition (abnormal chest X-ray with negative sputum TB smears and cultures, or pulmonary TB diagnosed by panel physician and fully treated by directly observed therapy). The screening includes a medical history and repeat physical exam. This screening primarily focuses on tuberculosis signs and symptoms, and includes a chest X-ray, and sputum collection for sputum TB smears (if required). Depending on the country of processing, refugees with other chronic or complex medical conditions may receive a cursory medical screening prior to departure in order to assess a refugee’s fitness for travel. However, this exam is not routinely conducted by panel physicians and is not required.

Pre-Embarkation Checks (PEC)

Depending on the country of processing, IOM physicians perform a pre-embarkation check within 24-48 hours of the refugee’s departure for the United States to assess fitness for travel and to administer presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites.

CDC is working with IOM and independent panel physicians in the Middle East to expand PDMS/PEC throughout the region.

Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees

In addition to vaccines received through national immunization programs and/or administered by NGOs, Syrian refugees may receive select vaccines as part of the Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees. Whether or not a Syrian refugee receives vaccines prior to departure depends on the country of processing, vaccine availability, and other factors. Refugees in Iraq and Jordan may receive bivalent oral polio (bOPV), MMR, and pentavalent (DTP-Hepatitis B-Hib) vaccines, depending on age. Hepatitis B surface antigen testing will be conducted for refugees receiving hepatitis B vaccine once testing kits are available.

All vaccines administered through the Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees, as well as records of historical/prior vaccines provided by NGOs and national programs, will be documented on the DS-3025 (Vaccination Documentation Worksheet) form. U.S. providers are strongly encouraged to review each refugee’s records to determine which vaccines were administered overseas.

In the next few years, CDC, in partnership with the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau for Populations, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), hopes to implement this vaccination program among all U.S.-bound refugees in the Middle East. Additional information about the CDC-PRM Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees is available on CDC’s Immigrant, Refugee, and Migrant Health website.

Presumptive Therapies for Intestinal Parasites

Syrian refugees departing from Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt may receive albendazole for soil-transmitted helminthic infection, and ivermectin for strongyloidiasis. Refugees departing from Jordan and Egypt receive presumptive treatment via directly observed therapy (DOT) at PEC. Syrians departing from Iraq may receive a single dose of albendazole and ivermectin, and due to security and logistical challenges, may be given a second dose of ivermectin to self-administer. At this time, Syrian refugees departing from Turkey, Lebanon, and Austria do not receive any presumptive parasitic treatment.

U.S. providers should refer to each refugee’s PDMS form to determine which interventions, including vaccinations and presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites, were administered overseas.

Additional information regarding presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites can be found here.

Post-Arrival Medical Screening

CDC recommends that refugees receive a post-arrival medical screening (domestic medical screening) within 30 days after arrival in the United States. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) reimburses providers for screenings conducted during the first 90 days after the refugee’s arrival.

The purpose of these more comprehensive examinations is to assess for health conditions and to introduce newly arrived refugees to the American healthcare system. CDC provides guidelines and recommendations for this medical screening, while state refugee health programs oversee its implementation. The screening is conducted by state refugee health programs or private physicians designated by these programs. Most state refugee health programs then collect data from this screening.

Health Information

This section describes the disease burden for specific diseases among the Syrian refugee community.

Communicable Disease

Tuberculosis

In 2014, Syria notified WHO of 3,576 cases of tuberculosis (TB) and an overall incidence rate of 17 cases per 100,000 population 36. Incidence rates of TB are similar (or lower) in countries where Syrian refugees are being processed, with the exception of Iraq, which has a relatively high incidence rate (Table 2). Additionally, the number of multi-drug resistant (MDR) TB cases in each country is relatively low. As TB incidence in Iraq is >20 per 100,000 population, Interferon-Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) or tuberculin skin test (TST) is still required as part of the overseas medical examination for Syrian refugees being processed in Iraq.

Table 2. Tuberculosis burden in countries processing Syrian refugees

| Country | Total cases notified | MDR-TB cases among notified pulmonary TB cases | Incidence (rate per 100,000 population) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New | Retreatment | |||

| Egypt | 7,467 | 160 | 89 | 15 |

| Iraq | 8,341 | 51 | 110 | 43 |

| Jordan | 405 | 14 | 7 | 5.5 |

| Lebanon | 683 | 5 | 16 | 5 |

| Turkey | 13,378 | 190 | 170 | 18 |

In a small sample of adult Syrian refugees (n=44) presenting at GeoSentinel sites after migration, 5 cases of active TB (3 pulmonary, 2 extrapulmonary) and 4 cases of latent TB infection (LTBI) were identified 38. Initial screening data from Texas and Illinois indicate that approximately 10% of newly arrived Syrian refugees have LTBI, as detected by IGRA/TST 39. This is consistent with findings from GeoSentinel surveillance data. However, preliminary screening data from Canada indicate substantially lower rates of LTBI in newly arriving Syrian refugees. Of 26,166 Syrian refugees screened upon arrival between November 2015 and February 2016, only 2 (<1%) were found to have LTBI 40.

Infectious Hepatitis

The prevalence of chronic infectious hepatitis (B and C) among Syrian refugees appears to be low. In a recent cross-sectional survey of Syrian refugees residing in Iraq (N=880), 3.86% (34/880) were found to be infected with hepatitis B virus 41. Screening performed in unaccompanied Syrian children (<18 years) revealed no cases of hepatitis B among 448 screened children 38. Initial domestic screening of Syrian refugees in Texas arriving between January 2012 and July 2016 found 1.2% (3/259) of those screened had hepatitis B infection 39. Until additional data become available that confirm these low rates, Syrian refugees should continue to be screened for chronic hepatitis B virus infection.

Estimated hepatitis C virus infection prevalence is quite low in the general Syrian population (0.4%), as well as in surrounding countries, including Iraq (0.2%), Jordan (0.3%), and Lebanon (0.2%) 42. Among high-risk groups in the same countries, hepatitis C prevalence was considerably higher, particularly in Syria, where prevalence was estimated to be 47.4% 42. Hepatitis C virus infection is a major health concern in Egypt, with prevalence estimated to be greater than 10% nationally 43, 44. Among Syrian refugees, few hepatitis C screening data are available. In the aforementioned cohort of 880 Syrian refugees living in Iraq, and 480 unaccompanied children screened in Berlin, no cases of hepatitis C were detected 38, 42. Until further data are available, those with risk factors, and those for whom routine screening in the U.S. is recommended (e.g., born during 1945-1965), should be screened in accordance with current U.S. recommendations.

HIV and Syphilis

HIV and syphilis appear to be uncommon in resettled Syrian refugees. Data collected from domestic medical screening of Syrian refugees in Texas arriving between January 2012 and July 2016 revealed low rates of HIV and syphilis infection. Of those screened, 0.8% (2/261) were found to be HIV-positive, and syphilis infection was found in 0.7% (1/140) 39. Although reported infection rates are low, routine screening according to the Domestic Refugee Screening Guidelines for HIV Infection and Sexually Transmitted Diseases should be followed until further data become available.

Parasitic Infections

The majority of Syrian refugees are receiving albendazole and ivermectin prior to departure to the United States. Routine post-arrival stool ova (eggs) and parasite testing is likely not cost-effective and is not routinely recommended for Syrian refugees. Domestic screening physicians and providers should refer to CDC’s Domestic Intestinal Parasite Guidance.

Giardiasis

Giardiasis has been detected in Syrian refugees and can be associated with subtle symptoms such as abdominal complaints, loose stool, flatulence, and eructation. Giardiasis has been associated with failure to thrive in children. A lower threshold to screen or test children younger than 5 years of age who may not verbalize symptoms or express overt signs of infection is reasonable. When screening is performed, stool antigen testing is more sensitive and convenient than stool ova and parasite examination. U.S. clinicians should note that overseas presumptive parasite treatments are not effective in treating Giardiasis.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is caused by infection with Leishmania parasites, which are spread by the bite of phlebotomine sand flies. Leishmaniasis is endemic to Syria. There are several different forms of leishmaniasis in people. The most common forms are cutaneous leishmaniasis, which causes skin sores, and visceral leishmaniasis, which affects several internal organs (usually spleen, liver, and bone marrow). Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form of the disease observed in Syrian refugees. L. tropica and L. major have been reported in Syrian refugees in Lebanon 45. In 2013, 1,033 new cases of leishmaniasis were reported in Lebanon, with approximately 97% of cases occurring in Syrian refugees 46. Cutaneous leishmaniasis has also been reported in refugees in Turkey 47, 48, as well as in Syrian refugees screened at a GeoSentinel site in Berlin, Germany 38.

Currently, there is no additional screening recommended to detect leishmaniasis. However, clinicians should be aware of the disorder and consider it in the differential diagnosis of any Syrian with chronic skin sores or other symptoms that might indicate infection (e.g., chronic cutaneous lesions). Information on the diagnosis and management of leishmaniasis may be accessed at the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases website.

Echinococcosis

Echinococcosis is a parasitic disease caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, a tapeworm found in dogs (definitive host), sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs (intermediate hosts). Echinococcosis is classified as either cystic or alveolar. Cystic echinococcosis (CE), or hydatid disease, is the primary form of echinococcosis found in Syrian refugees. Most people with CE infections are asymptomatic. However, in some cases, CE causes harmful, slow-growing cysts in the liver, lungs, and other organs. These cysts often grow for years and go unnoticed and neglected. Clinical presentation is highly variable. Most often, clinical presentation is due to mass effect—as the cyst grows, it impinges on local tissues causing discomfort and/or abnormal test results (e.g., increased liver function tests). Infection may also be incidentally noted when diagnostic procedures are done for other reasons (e.g., chest X-ray). Cyst rupture may result in anaphylactic reactions, including death, when the contents of the cyst are released. This can occur spontaneously following trauma, or, most importantly, when clinical evaluation/intervention is being attempted.

Currently, no additional screening is recommended for asymptomatic refugees. However, when a cystic lesion is noted, echinococcosis diagnosis should be considered. Expert advice should be obtained prior to performing any invasive diagnostic or intervention procedures. Further information is available from the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases website.

Non-Communicable Diseases

Chronic and non-communicable diseases have been reported in Syrian refugees. Chronic and non-communicable conditions in this population include anemia, cancer, hypertension, diabetes, malnourishment, renal disease, and hemoglobinopathies/thalassemias.

In a recent survey of Syrian refugee households (n=1550) residing in non-camp settings in Jordan, half of all households reported having at least one household member with a previous diagnosis with one of five non-communicable diseases: arthritis, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, or hypertension 49. Among adults (>18 years of age) in the survey population, hypertension prevalence was highest (10.7%), followed by arthritis (7.1%), diabetes (6.1%), cardiovascular disease (4.1%), and chronic respiratory disease (2.9%). However, disease prevalence was substantially higher for older refugees, particularly those 60 years of age or older (Table 3) 49. Additionally, in a separate survey (n=210) among elderly Syrian refugees (>60 years of age) living in Lebanon, 22% of respondents reported high cholesterol, while 15% reported chronic pain. Digestive tract and neurological diseases were reported by 9% and 5% of survey participants, respectively 50.

Table 3. Chronic disease prevalence among Syrian refugees in Jordan by age group 49

| Age in years | Survey Total N | Hypertension | Cardiovascular Disease | Diabetes | Chronic Respiratory Disease | Arthritis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 0-17 | 5147 | 6 | 0.1 | 20 | 0.4 | 8 | 0.2 | 153 | 3.0 | 18 | 0.3 |

| 18-39 | 3019 | 60 | 2.0 | 25 | 0.8 | 26 | 0.9 | 66 | 2.2 | 75 | 2.5 |

| 40-59 | 1040 | 220 | 21.2 | 78 | 7.5 | 125 | 12.0 | 39 | 3.8 | 154 | 14.8 |

| 60+ | 373 | 195 | 52.1 | 80 | 21.4 | 121 | 32.4 | 22 | 5.9 | 85 | 23.7 |

| Adult Prevalencea | 4433 | 475 | 10.7 | 183 | 4.1 | 272 | 6.1 | 127 | 2.9 | 314 | 7.1 |

a “Adult” defined as any individual >18 years of age

Source: Doocy et al 2015

Anemia

Anemia, as a marker for overall micronutrient deficiency, appears to be common in Syrian refugees. An evaluation of anemia prevalence in the Zaatari refugee camp and surrounding areas showed that 48.4% of children younger than 5 years of age, and 44.8% of women 15-49 years of age suffered from anemia 51. These data indicate a severe problem of public health significance, as classified by WHO, as prevalence is well over 40% in these groups 52.

Hemoglobinopathy / Thalassemia

Hemoglobinopathies (thalassemias) are prevalent in Syria, and throughout Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries. Approximately 5% of the Syrian population are carriers of beta thalassemia trait, and less than 5% are carriers of alpha thalassemia trait 53. These disorders vary from severe, life-threatening disease needing frequent transfusion and ongoing care (e.g., beta thalassemia major), to very minor or asymptomatic disease presenting with mild anemia or red blood cell anomalies (e.g., alpha-thalassemia silent carrier). These disorders should be considered in any individual with anemia and/or other red blood indices anomalies and appropriate diagnostics performed (including haemoglobin electrophoresis). Sickle cell disease is uncommon, and less than 1% of the population are carriers for the disease 54. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD) has been reported in 3% of the Syrian population 55.

Genetic Disorders

Familial Mediterranean Fever is a common inherited disorder in the Syrian population. Familial Mediterranean Fever is an autosomal recessive inflammatory disease causing periodic fever and pain in serosal membranes, including those of the abdomen, chest, and joints. Past studies revealed that the mean age of disease onset was 14 years of age, with a male-to-female preponderance of 4:1. In an assessment of healthy individuals, 17.5% were identified as carriers of Familial Mediterranean Fever 56.

Lead Toxicity

Increased blood lead levels may be uncommon in Syrian children, although additional data are needed. Domestic screening in Syrian refugee children (aged 6 months to 16 years) in Texas January 2016 to July 2016 found 1.3% (N=158) of those screened had elevated lead levels (>5 µg/dL) 39. However, until more data are available, routine screening should be performed, according to CDC’s Domestic Lead Screening guidelines.

Malnutrition

Preliminary findings from a study in the Zaatari refugee camp and surrounding area indicated a low prevalence of global acute malnutrition among Syrian refugee children aged 6-59 months (1.2% and 0.8%, respectively). However, the prevalence of chronic malnutrition (stunting) was more pronounced with 17% of children inside the camp and 9% outside the camp affected 51.

Renal Disease

No national data exist on the prevalence of renal disease in the Syrian population. In a pre-crisis, cross-sectional survey of hemodialysis sites in Aleppo, Syria, 550 patients (0.022% of the total population) were receiving hemodialysis. Hemodialysis patients ranged in age from 5 to 82 years with a mean of 44.7 years. The top three causes of end-stage renal disease in this population were hypertension (21.1%), glomerulonephritis (20.5%), and diabetes (19.5%). Hereditary causes were identified in 6.2% of this group. The low rate of hemodialysis in Aleppo was attributed to prohibitively high cost, high mortality, and low rates of ultimate transplantation 57.

Tobacco Usage

Prior to the crisis in Syria, tobacco usage was very high. It was estimated that 60% of men and 17% of women smoked cigarettes, and 20% of men and 5% of women used water pipes (hookahs or nargiles) 58. According to this study, most cigarette smokers were daily smokers, while water pipe users were intermittent users, often smoking in social settings 58.

Tobacco use is also reported to be quite high among Syrian adolescents. Water pipes or hookahs have quickly replaced cigarettes as the most popular method of tobacco use among youth throughout the Middle East 59. More than 20% of adolescents (13-15 years of age) used tobacco products other than cigarettes. When stratified by gender, nearly 30% of boys and more than 15% of girls 13-15 years of age use tobacco products 60.

Traumatic Injuries

In a study of refugees living in Jordan and Lebanon, 5.7% of refugees had significant injuries directly related to the conflict. One out of every 15 refugees in Jordan, and 1 in 30 refugees in Lebanon had suffered war-related injuries 61. Of the reported war-related injuries, 58% were due to bombing, shrapnel, and gunshot wounds, and 25% were from falls and burns 61.

Mental Health

A recent study, which included more than 6,000 refugee adults and children in Syria, Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan, found 54% suffered from a “severe emotional disorder,” including depression and anxiety 62.

Table 4 shows the WHO projections of the prevalence of mental health disorders in adults affected by emergencies 63.

| Before emergency (12-month prevalence)b | After emergency (12-month prevalence) | |

|---|---|---|

| Severe disorder (psychosis, severe depression, severely disabling anxiety, etc.) | 2-3% | 3-4% c |

| Mild or moderate disorder (mild/moderate depression and anxiety, etc.) | 10% | 15-20% d |

| Normal distress/other psychological reactions (no disorder) | No estimate | Large percentage |

a Actual observed rates may vary depending on setting and assessment method. b Assumed baseline rates are median rates across countries as observed in World Mental Health Survey, 2000. c Estimation based on the assumption that traumatic events and loss may contribute to a relapse (of a previously stable condition) and may cause severe, disabling forms of mood and anxiety disorders. d Traumatic events and loss are known to increase the risk of depression and anxiety disorders, including PTSD.

Source: World Health Organization, 2012

Given the complexity of the situation in Syria and the extreme violence and uncertainty that many Syrian refugees have experienced first-hand, the prevalence of mild-to-moderate or severe disorders may be higher than previous projections. Although mental health professionals should be careful not to over-diagnose clinical mental disorders among displaced Syrians 34, a high index of suspicion for mental health conditions should be maintained.

Pediatric Mental Health

In a study conducted in Turkey’s Islahiye Camp, researchers found that Syrian refugee children had experienced very high levels of trauma. Of the children surveyed, 44% reported symptoms of depression, and 45% showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 10 times the prevalence among children worldwide 64. U.S. communities that are preparing to receive Syrian refugees should establish connections with pediatric mental health providers and other community resources for children who have suffered traumatic events.