FoodNet 2020 Preliminary Data

Documenting the major sources of and trends in foodborne illness provides important information needed to determine whether prevention measures are working. Each year, FoodNet reports on the number of infections in the FoodNet surveillance area from pathogens transmitted commonly through food.

Key Findings from 2020 Surveillance Data

Infections monitored by FoodNet markedly decreased in 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic likely played a role in the decrease.

Campylobacter and Salmonella are by far the most common infections reported.

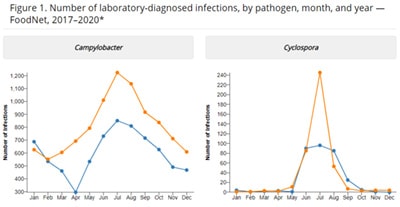

This year’s report summarizes 2020 preliminary surveillance data and describes 2020 incidence compared with the average incidence for 2017–2019 for infections caused by Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia. The report also summarizes cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) for 2019. Laboratory tests, including cultures and culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs), detected these pathogens.

- Observed incidences of infections monitored by FoodNet decreased markedly in 2020 compared with the previous 3 years.

- The 26% overall decrease was the largest single-year change in incidence during 25 years of FoodNet surveillance.

- However, the extent to which these reductions reflect actual decreases in illnesses is unknown.

- In March 2020, the United States declared a national emergency in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Officials implemented stay-at-home orders, restaurant closures, school and childcare closures, federal travel restrictions, and other public health interventions. These interventions and other health-care related factors likely influenced exposure to and detection of enteric infections.

- Exposure: Interventions to slow the spread of COVID-19 and other changes in hygiene and daily life likely influenced exposures to enteric pathogens.

- Detection: Other factors, such as changes in healthcare delivery, healthcare-seeking behaviors, and laboratory capacity, may have decreased the detection of enteric infections.

- Incidence of Campylobacter, Salmonella, STEC, and Vibrio infections, which had been increasing in previous years, decreased during 2020. Incidence of Cyclospora and Yersinia infections did not change.

- The proportion of enteric infections that resulted in hospitalization increased slightly.

- The percentage of infections initially diagnosed by culture versus CIDTs remained stable, indicating that clinical laboratory testing practices did not significantly contribute to decreases in reported infections.

- Changes in clinical and public health laboratory capacity might have contributed to decreases in the percentage of specimens with a culture done to obtain an isolate after a positive CIDT result.

Interpreting Changes in Incidence of Infections

Was the COVID-19 pandemic responsible for the decreases in infections?

Widespread interventions to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, likely contributed to decreases in incidence of infections. In addition, changes to daily life, hygiene, healthcare-seeking behaviors, healthcare delivery, and laboratory capacity all likely contributed.

Which pandemic-related changes may have led to fewer exposures?

Many interventions to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2, such as restaurant closures, likely contributed to fewer people being exposed to foodborne pathogens. Additionally, infections linked to international travel decreased markedly after pandemic-related travel restrictions were imposed.

Which pandemic-related factors may have led to fewer diagnoses?

Changes in healthcare-seeking behaviors, broader use of telehealth, and other factors may have limited the diagnosis and detection of cases. For example, emergency department visits decreased markedly early in the pandemic, with the largest declines in visits for abdominal pain and other digestive symptoms.

Why might have hospitalizations increased?

Reasons for the 2% increase in the proportion of infections resulting in hospitalization are likely twofold. First, fewer people with mild illness might have sought care. Second, people who did seek care might have waited until their illness was severe.

Do we know everything that contributed to the decreases?

No. The pandemic and corresponding public health response make explaining changes in the observed incidences of infections challenging. In addition to factors mentioned here, unknown ones might have contributed to fewer exposures, infections, and detections.

Continued surveillance may improve our understanding of how the pandemic affected the incidence of infections and may identify prevention measures and new strategies that target particular pathogens and serotypes.

Are the decreases in infections real or the result of decreased detection?

The number of infections reported to FoodNet decreased in 2020, and the data suggest that this was likely due to both

- decreased exposure to pathogens, resulting in real decreases in infections and

- decreased detection of infections, meaning infections occurred but were not reported.

Some findings suggest that real decreases occurred. For example, international travel decreased, and so did infections linked to international travel.

Why did some pathogens decrease more than others?

Assessing how various factors affected individual pathogens is difficult. However, decreases in international travel and foodborne outbreaks likely contributed to the differences.

Some pathogens are linked commonly to international travel, so pandemic-related travel restrictions likely meant fewer people were exposed to them. The same may apply to pathogens linked commonly to foodborne disease outbreaks.

Why did some pathogens or serotypes not decrease in incidence?

The findings suggest two likely explanations of why infections caused by some pathogens or serotypes did not decrease during 2020.

Factors that led to increased infections in previous years might have been prevalent in 2020, despite the pandemic. For example, infections caused by Salmonella serotype Infantis increased in 2019 and did not change in 2020. A highly resistant strain of Infantis found in chicken has been causing an increase in infections that likely continued in 2020.

Public health interventions, changes to healthcare-seeking behavior, and other factors might not have affected some pathogens and serotypes as much as others. For example, infections with Salmonella serotype Hadar, which is found commonly in poultry, increased by 615%, with all outbreak-related infections linked to backyard poultry. As pandemic-related restrictions resulted in fewer people leaving home, some turned to hobbies at home, including raising flocks.

Questions and Answers About Food Safety

Since 1996, FoodNet has been counting cases and tracking trends for infections transmitted commonly through food. Information gathered on which illnesses are decreasing and which are increasing provides a foundation for food safety policy and prevention efforts. FoodNet’s surveillance data, such as those in this report, show where efforts are needed to reduce foodborne illnesses. Learn more about FoodNet >

CDC uses the best scientific methods and information available to monitor, investigate, control, and prevent foodborne illness. Using epidemiology and laboratory science, CDC assesses public health threats. CDC works closely with state health departments to monitor the frequency of specific diseases and to conduct national surveillance for the diseases it monitors.

When food safety threats appear, CDC collaborates with public health partners, including state health departments, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), to conduct epidemiologic and laboratory investigations to determine the causes of these threats and how they can be controlled. Although CDC does not regulate the safety of food, CDC works with regulatory agencies to develop robust food safety policies and assess the effectiveness of current prevention efforts. CDC provides independent scientific assessment of what the problems are, how they can be controlled, and where the gaps exist in our knowledge. You can find more information on foodborne illness and CDC’s prevention activities on CDC’s Food Safety website.

Government regulation related to food safety is the responsibility of FDA, USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS), the National Marine Fisheries Service, and other regulatory agencies.

Recent regulatory efforts include the following:

- FDA launched the New Era of Smarter Food Safety Initiative in 2019, building upon the work the FDA has done through implementation of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA).

- The New Era of Smarter Food Safety Blueprint, released in 2020, outlines FDA’s goals over the next decade to leverage new technologies, tools and approaches to create a safer and more digital, traceable food system.

- The blueprint focuses on four priority areas, called core elements: enhanced traceability, smarter tools and approaches for prevention and outbreak response, new business models and retail modernization, and food safety culture.

- Since the release of the blueprint, FDA has made significant progress in working toward the goals outlined, even in the midst of a pandemic. More information on activities planned for this year is available in the FDA’s list of New Era of Smarter Food Safety Select Activities for 2021.

- USDA-FSIS routinely collects and tests samples from establishments that produce chicken and turkey products to assess whether they are meeting performance standards.

- Each month, the agency posts the aggregate sampling results for the prior 12 months. For example, during the 12-month period ending on June 30, 2021, USDA-FSIS calculated that about 6.5% of chicken parts (legs, breasts, and wings) tested positive for Salmonella and about 15% of chicken parts tested positive for Campylobacter.

- If an establishment does not meet or is trending towards not meeting performance standards, establishments will be notified, and FSIS will take follow-up actions to determine if the establishment’s food safety system is adequately controlling pathogens.

- Although products from establishments that fail to meet the standards are still sold, USDA-FSIS takes actions to encourage better performance.

- USDA-FSIS makes the names of establishments and whether they did or did not meet the Salmonella standards available online so buyers and consumers can make informed decisions about purchases, creating an incentive for establishments to meet standards.

- In June 2021, USDA-FSIS issued guidelines for controlling Salmonella in raw poultry and guidelines for controlling Campylobacter in raw poultry, including chicken carcasses, parts, and ground products.

- In July 2021, USDA-FSIS updated industry guidelines for minimizing the risk of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in beef (including veal) slaughter operations and processing operations. [PDF – 64 pages]

- USDA-FSIS proposed performance standards for Salmonella in raw beef products and Campylobacter in ground poultry products, and is developing performance standards for Salmonella contamination of raw pork products.

CDC works closely with regulatory agencies as they, along with industry, develop and implement measures to make our food safer.

Following four simple food safety steps – clean, separate, cook, and chill – can help protect you and your loved ones when preparing food at home.

- Clean

Wash your hands and work surfaces before, during, and after preparing food. Germs can survive in many places around your kitchen, including on your hands, utensils, cutting boards, and countertops. - Separate

Separate raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs from ready-to-eat foods. Use separate cutting boards and keep raw meat away from other foods in your shopping cart and refrigerator. - Cook

Cook food to the right internal temperature to kill harmful bacteria. Use a food thermometer. - Chill

Keep your refrigerator at 40°F or below. Refrigerate leftovers within 2 hours of cooking (or within 1 hour if food is exposed to a temperature above 90°F, like in a hot car).

Find out steps you can take to prevent infection from the following pathogens:

Suggested citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Decreased Incidence of Infections Caused by Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food During the COVID-19 Pandemic — Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2017–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 September 23.