Fascioliasis

[Fasciola gigantica] [Fasciola hepatica]

Causal Agent

The trematodes Fasciola hepatica (also known as the common liver fluke or the sheep liver fluke) and Fasciola gigantica are large liver flukes (F. hepatica: up to 30 mm by 15 mm; F. gigantica: up to 75 mm by 15 mm), which are primarily found in domestic and wild ruminants (their main definitive hosts) but also are causal agents of fascioliasis in humans.

Although F. hepatica and F. gigantica are distinct species, “intermediate forms” that are thought to represent hybrids of the two species have been found in parts of Asia and Africa where both species are endemic. These forms usually have intermediate morphologic characteristics (e.g. overall size, proportions), possess genetic elements from both species, exhibit unusual ploidy levels (often triploid), and do not produce sperm. Further research into the nature and origin of these forms is ongoing.

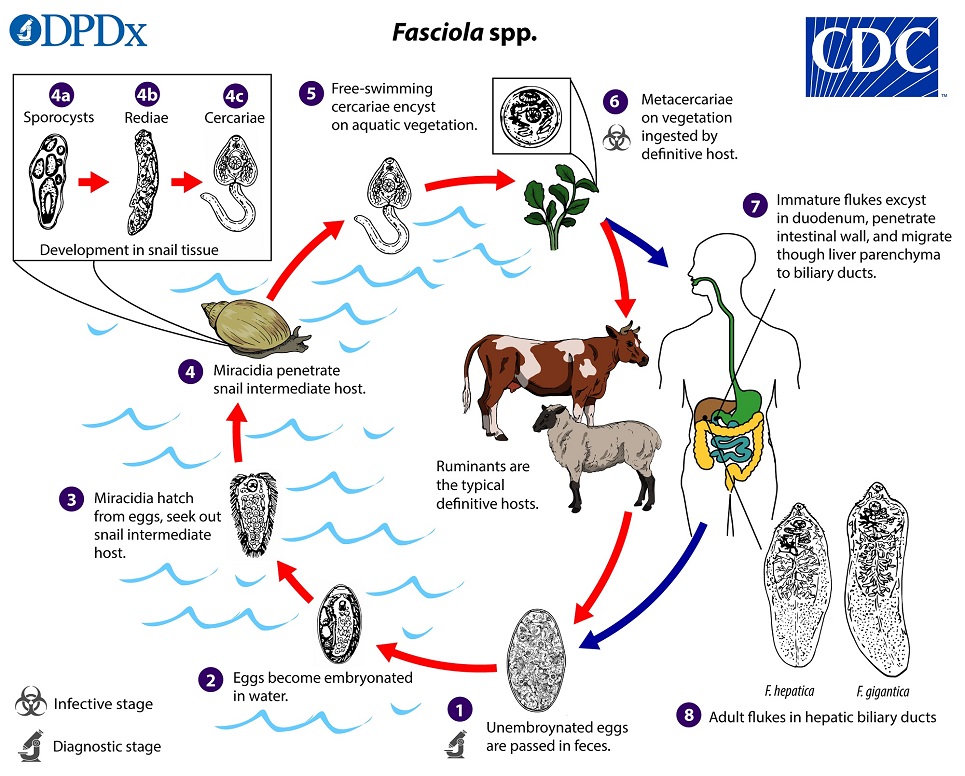

Life Cycle

Immature eggs are discharged in the biliary ducts and passed in the stool  . Eggs become embryonated in freshwater over ~2 weeks

. Eggs become embryonated in freshwater over ~2 weeks  ; embryonated eggs release miracidia

; embryonated eggs release miracidia  , which invade a suitable snail intermediate host

, which invade a suitable snail intermediate host  . In the snail, the parasites undergo several developmental stages (sporocysts

. In the snail, the parasites undergo several developmental stages (sporocysts  , rediae

, rediae  , and cercariae

, and cercariae  ). The cercariae are released from the snail

). The cercariae are released from the snail  and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation or other substrates. Humans and other mammals become infected by ingesting metacercariae-contaminated vegetation (e.g., watercress)

and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic vegetation or other substrates. Humans and other mammals become infected by ingesting metacercariae-contaminated vegetation (e.g., watercress)  . After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum

. After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum  and penetrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity. The immature flukes then migrate through the liver parenchyma into biliary ducts, where they mature into adult flukes and produce eggs

and penetrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity. The immature flukes then migrate through the liver parenchyma into biliary ducts, where they mature into adult flukes and produce eggs  . In humans, maturation from metacercariae into adult flukes usually takes about 3–4 months; development of F. gigantica may take somewhat longer than F. hepatica.

. In humans, maturation from metacercariae into adult flukes usually takes about 3–4 months; development of F. gigantica may take somewhat longer than F. hepatica.

Hosts

Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica are primarily parasites of domestic and wild ruminants (most commonly, sheep, cattle, and goats; also, camelids, cervids, and buffalo). Infections occasionally occur in aberrant, non-ruminant herbivore hosts, including equids, lagomorphs, macropods, and rodents. Detection of Fasciola spp. eggs in the feces of carnivores probably represents spurious passage following consumption of contaminated liver.

The snail intermediate hosts for Fasciola spp. are in the family Lymnaeidae, particularly species in the genera Lymnaea, Galba, Fossaria, and Pseudosuccinea. At least 20 snail species have been identified as intermediate hosts for one or more Fasciola spp. Snail species may differ with respect to their suitability to serve as intermediate hosts for F. hepatica versus F. gigantica; host ranges for both Fasciola spp. are a subject of ongoing research.

Geographic Distribution

Fasciola hepatica is found on all inhabited continents, in more than 70 countries, particularly where sheep or cattle are raised. Human infections have been reported in parts of Europe, the Middle East, Latin America (e.g., Bolivia and Peru), the Caribbean, Asia, Africa, and rarely in Australia. Although the conditions for F. hepatica life cycle exist in the some parts of the United States, most of the reported U.S. cases of F. hepatica infection in humans have occurred in immigrants who became infected in other countries.

Fasciola gigantica is mainly found in tropical and subtropical regions. Human cases have been reported in parts of Asia and Africa, as well as in Hawaii and Iran.

“Intermediate forms” have been reported from areas, particularly in Asia, where both F. hepatica and F. gigantica are endemic. However, other non-sperm-producing forms with unusual ploidy and morphology occasionally have been reported in areas where the two species are not sympatric (e.g., the United Kingdom), which underscores the need for more research into atypical forms.

Clinical Presentation

Fasciola spp. infection in humans has two main phases, which may or may not be associated with symptoms or other clinical manifestations. During the early phase of the infection (usually referred to as the acute phase; also, the migratory, invasive, hepatic, parenchymal, or larval phase), the period when the larval fluke is migrating from the intestines and through the liver parenchyma, larval migration can be associated with inflammation, tissue destruction, and toxic/allergic reactions. Nonspecific symptoms/signs (e.g., abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, hepatomegaly, malaise, fever, cough) and laboratory abnormalities (e.g., peripheral eosinophilia, elevated transaminase levels) may develop. Occasionally, larval flukes migrate to ectopic sites, such as the lungs, subcutaneous tissue, pancreas, genitourinary tract, eyes, or brain.

During the chronic phase of the infection (also referred to as the biliary or adult phase), clinical manifestations, if any, may develop months to years postexposure and include inflammation or blockage of bile ducts or the gallbladder (e.g., cholangitis, cholecystitis), which can be intermittent. Inflammation of the pancreas may also occur.

Fasciola hepatica eggs.

Eggs of Fasciola spp. are broadly ellipsoidal, are operculated, measure 130–150 µm long by 60–90 µm wide, and are passed unembryonated in feces. Fasciola spp. eggs can be difficult to distinguish from Fasciolopsis buski eggs, although the abopercular end of Fasciola spp. eggs often have a roughened or irregular area. Eggs are often reported as “Fasciola/Fasciolopsis” eggs due to morphologic overlap. Also, egg size cannot reliably distinguish F. hepatica from F. gigantica.

F. hepatica adults.

F. hepatica adults observed in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Intermediate hosts of Fasciola spp.

Diagnostic Findings

Eggs can be detected by light microscopy during the chronic (adult) phase of infection. Eggs can be recovered from stool or material obtained by duodenal or biliary drainage or aspiration. F. hepatica and F. gigantica eggs are effectively morphologically indistinguishable and also can be difficult to distinguish from (or can be confused with) eggs of Fasciolopsis buski and eggs of some Echinostoma spp. Adult flukes may be detected with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP]). Migrating larval flukes may be detected in histologic sections.

False fascioliasis (pseudofascioliasis) refers to the presence of eggs in the stool not because of an actual infection but rather because of recent ingestion of liver contaminated with eggs, which are not infective for humans. The potential for misdiagnosis can be avoided by having the patient abstain from eating liver for several days before a repeat stool examination.

Morphologic comparison with other intestinal parasites

Antibody Detection

Serologic testing can be useful in the acute phase of infection because specific antibodies to Fasciola may become detectable 2 to 4 weeks after acquisition of infection, whereas egg production typically does not start until at least 3 to 4 months after exposure. Serologic testing can also be of value for cases of chronic Fasciola infection in persons with low-level or sporadic egg production, as well as in persons with ectopic infection. It may also help rule out pseudofascioliasis associated with ingestion of parasite eggs in sheep or beef liver.

The typical approach for immunodiagnosis of human F. hepatica infection includes use of an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with excretory-secretory (ES) or recombinant antigens and confirmatory testing of EIA-positive specimens with an immunoblot assay.

CDC has developed a CLIA-approved immunoblot assay for the diagnosis of Fasciola infection, which is based on a recombinant F. hepatica antigen (FhSAP2)*. A positive reaction is defined as the presence of a band at ~38 kDa. The sensitivity of the assay is ≥94% (16/17) and the specificity is ≥98% (113/115) for humans with chronic Fasciola infection. This assay has not yet been validated for acute Fasciola infection.

*Shin, S.H., Hsu, A., Chastain, H.M., Cruz, L.A., Elder, E.S., Sapp, S.G., McAuliffe, I., Espino, A.M. and Handali, S., 2016. Development of two FhSAP2 recombinant–based assays for immunodiagnosis of human chronic fascioliasis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 95(4), pp.852-855.

Laboratory Safety

Standard precautions apply for the processing of stool, serum, and tissue specimens. Fasciola spp. eggs cannot infect humans because of the need for larval development in an intermediate host (snail).

Suggested Reading

Ichikawa-Seki, M., Peng, M., Hayashi, K., Shoriki, T., Mohanta, U.K., Shibahara, T. and Itagaki, T., 2017. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals that hybridization between Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica occurred in China. Parasitology, 144(2), pp.206-213.

Tolan Jr, R.W., 2011. Fascioliasis due to Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica infection: an update on this ‘neglected’ neglected tropical disease. Laboratory Medicine, 42(2), pp.107-116.

Alatoom, A., Cavuoti, D., Southern, P. and Gander, R., 2008. Fasciola hepatica infection in the United States. Laboratory Medicine, 39(7), pp.425-428.

DPDx is an educational resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention, control, and treatment visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.