Facts about Esophageal Atresia

What is Esophageal Atresia?

Esophageal atresia is a birth defect in which part of a baby’s esophagus (the tube that connects the mouth to the stomach) does not develop properly.

Esophageal atresia is a birth defect of the swallowing tube (esophagus) that connects the mouth to the stomach. In a baby with esophageal atresia, the esophagus has two separate sections—the upper and lower esophagus—that do not connect. A baby with this birth defect is unable to pass food from the mouth to the stomach, and sometimes difficulty breathing.

Esophageal atresia often occurs with tracheoesophageal fistula, a birth defect in which part of the esophagus is connected to the trachea, or windpipe.

Types of Esophageal Atresia

There are four types of esophageal atresia: Type A, Type B, Type C and Type D.

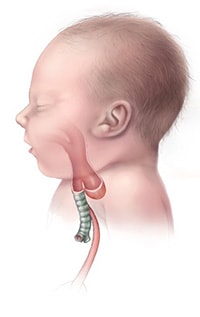

- Type A is when the upper and lower parts of the esophagus do not connect and have closed ends. In this type, no parts of the esophagus attach to the trachea.

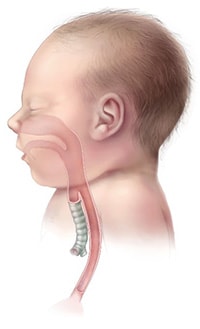

- Type B is very rare. In this type the upper part of the esophagus is attached to the trachea, but the lower part of the esophagus has a closed end.

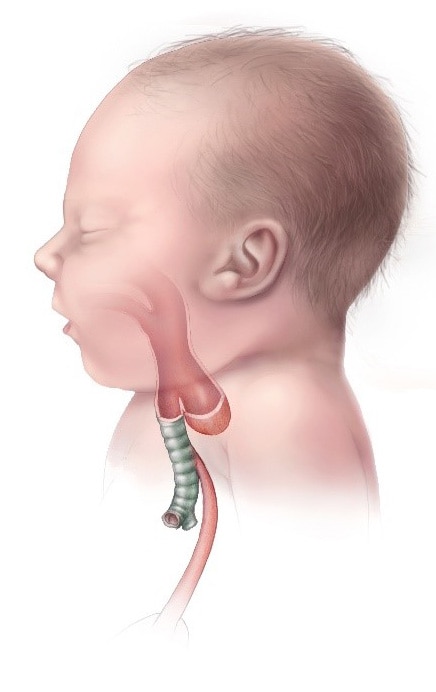

- Type C is the most common type. In this type the upper part of the esophagus has a closed end and the lower part of the esophagus is attached to the trachea, as is shown in the drawing.

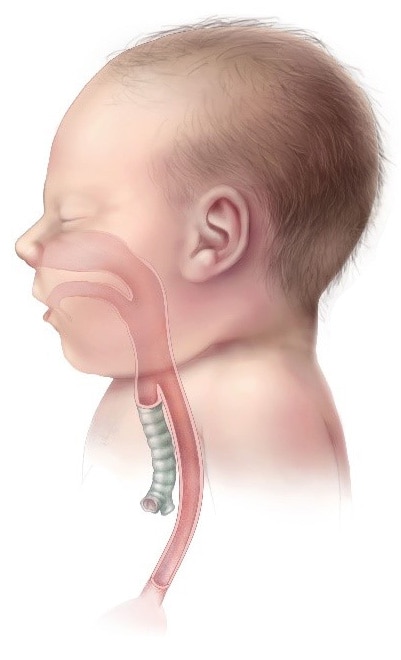

- Type D is the rarest and most severe. In this type the upper and lower parts of the esophagus are not connected to each other, but each is connected separately to the trachea.

How Many Babies are Born with Esophageal Atresia?

Researchers estimate that about 1 in every 4,100 babies is born with esophageal atresia in the United States.1 This birth defect can occur alone, but often occurs with other birth defects.

Causes

Like many families of children with a birth defect, CDC wants to find out what causes them. Understanding the factors that can increase the chance of having a baby with a birth defect will help us learn more about the causes. CDC funds the Centers for Birth Defects Research and Prevention, which collaborate on large studies such as the National Birth Defects Prevention Study (NBDPS; births 1997-2011) and the Birth Defects Study To Evaluate Pregnancy exposureS (BD-STEPS; began with births in 2014), to understand the causes of and risks for birth defects, including esophageal atresia.

The causes of esophageal atresia in most babies are unknown. Researchers believe that some instances of esophageal atresia may be caused by abnormalities in the baby’s genes. Nearly half of all babies born with esophageal atresia have one or more additional birth defects, such as other problems with the digestive system (intestines and anus), heart, kidneys, or the ribs or spinal column.2

Recently, CDC reported on important findings about some factors that increase the risk of having a baby with esophageal atresia:

- Paternal age – Older age of the father is related to an increased chance of having a baby born with esophageal atresia.3

- Assisted reproductive technology (ART) – Women who used ART to become pregnant have an increased risk of having a baby with esophageal atresia compared to women who did not use ART.4

CDC continues to study birth defects, such as esophageal atresia, and how to prevent them. If you are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant, talk with your doctor about ways to increase your chances of having a healthy baby.

Diagnosis

Esophageal atresia is rarely diagnosed during pregnancy. Esophageal atresia is most commonly detected after birth when the baby first tries to feed and has choking or vomiting, or when a tube inserted in the baby’s nose or mouth cannot pass down into the stomach. An x-ray can confirm that the tube stops in the upper esophagus.

Treatment

Once a diagnosis has been made, surgery is needed to reconnect the two ends of the esophagus so that the baby can breathe and feed properly. Multiple surgeries and other procedures or medications may be needed, particularly if the baby’s repaired esophagus becomes too narrow for food to pass through it; if the muscles of the esophagus don’t work well enough to move food into the stomach; or if digested food in the stomach consistently moves back up into the esophagus.

References

- Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, Meyer RE, Correa A, Alverson CJ, Lupo PJ, Riehle‐Colarusso T, Cho SJ, Aggarwal D, Kirby RS. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010–2014. Birth Defects Research. 2019; 111(18): 1420-1435.

- Chittmittrapap S, Spitz L, Kiely EM, Brereton RJ. Oesophageal atresia and associated anomalies. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64(3):364-68.

- Green RF, Devine O, Crider KS, Olney RS, Archer N, Olshan AF, Shapira SK; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Association of paternal age and risk for major congenital anomalies from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997 to 2004. Ann Epidemiol. 2010 Mar 31;20(3):241-9.

- Reefhuis J, Honein MA, Schieve LA, Correa A, Hobbs CA, Rasmussen SA. Assisted reproductive technology and major structural birth defects in the United States. Hum Reprod. 2009 Feb 1;24(2):360-6.