Facts about dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries (d-TGA)

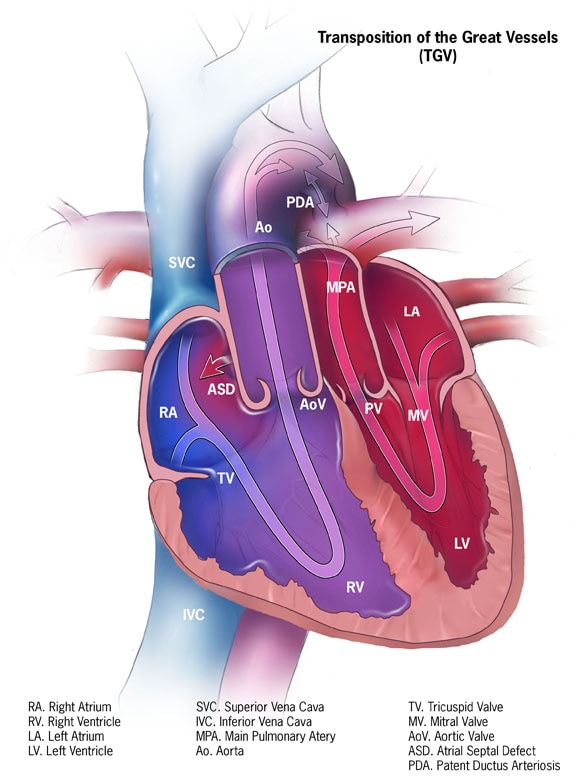

Dextro-Transposition (pronounced DECKS-tro trans-poh-ZI-shun) of the Great Arteries or d-TGA is a birth defect of the heart in which the two main arteries carrying blood out of the heart – the main pulmonary artery and the aorta – are switched in position, or “transposed.”

What is dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries (d-TGA)?

Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries or d-TGA is a birth defect of the heart in which the two main arteries carrying blood out of the heart – the main pulmonary artery and the aorta – are switched in position, or “transposed.” Because a baby with this defect may need surgery or other procedures soon after birth, d-TGA is considered a critical congenital heart defect (CCHD). Congenital means present at birth.

In transposition of the great arteries, the aorta is in front of the pulmonary artery and is either primarily to the right (dextro) or to the left (levo) of the pulmonary artery. Levo-TGA is rarer than dextro-TGA. Dextro-TGA is often simply called “TGA.” However, “TGA” is a broader term that includes both dextro-TGA (d-TGA) and levo-TGA (l-TGA), or congenitally corrected TGA, which is not discussed here.

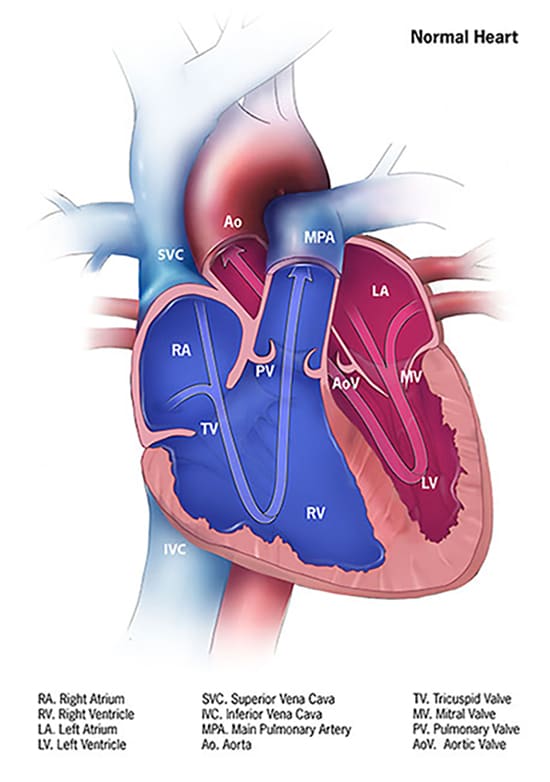

In a baby without a congenital heart defect, the right side of the heart pumps oxygen-poor blood from the heart to the lungs through the pulmonary artery. The left side of the heart pumps oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body through the aorta. The aorta is usually behind the pulmonary artery.

In babies with d-TGA, oxygen-poor blood from the body enters the right side of the heart. But, instead of going to the lungs, the blood is pumped directly back out to the rest of the body through the aorta. Oxygen-rich blood from the lungs entering the heart is pumped straight back to the lungs through the main pulmonary artery.

Often, babies with d-TGA have other heart defects, such as a hole between the lower chambers of the heart (a ventricular septal defect) or the upper chambers of the heart (an atrial septal defect) that allow blood to mix so that some oxygen-rich blood can be pumped to the rest of the body. The patent ductus arteriosus also allows some oxygen-rich blood to be pumped to the rest of the body.

Learn more about how the heart works »

Occurrence

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 1,153 babies are born with TGA each year in the United States.1 This means that every 1 in 3,413 babies born in the US is affected by this defect.

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of congenital heart defects, such as d-TGA, among most babies are unknown. Some babies have congenital heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. Heart defects are also thought to be caused by the combination of genes and other risk factors such as things the mother comes in contact with in her environment, or what the mother eats or drinks, or certain medications she uses.

Read more about CDC’s work on causes and risk factors »

Diagnosis

This defect may be diagnosed during pregnancy or soon after the baby is born.

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, there are screening tests that the mother can have (also called prenatal tests) to check for birth defects and other conditions. D-TGA may be diagnosed during pregnancy with an ultrasound test (which creates pictures of the baby). Some findings from the ultrasound may make the health care provider suspect a baby could have d-TGA. If so, the health care provider can request a fetal echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis. A fetal echocardiogram is a more detailed ultrasound of the baby’s heart. This test can show problems with the structure of the heart and how the heart is working with this defect.

After the Baby is Born

Symptoms occur at birth or very soon afterwards. How severe the symptoms are will depend on whether there is a way for blood to mix and for oxygen-rich blood to get out to the rest of the body. For example, if an infant with d-TGA has another defect, like an atrial septal defect (ASD), the ASD forms a passageway for some oxygen-rich blood to be pumped to the rest of the body. This infant with both d-TGA and an ASD may not have as severe symptoms as infants whose hearts don’t have any mixing of blood. Infants with d-TGA can have a bluish looking skin color—called cyanosis—because their blood doesn’t carry enough oxygen. Infants with d-TGA or other conditions causing cyanosis can have symptoms such as:

- Problems breathing

- Pounding heart

- Weak pulse

- Ashen or bluish skin color

- Poor feeding

Because the infant might be bluish in color and have trouble breathing, d-TGA is usually diagnosed within the first week of life. The health care provider can request one or more tests to confirm the diagnosis. The most common test is an echocardiogram. An echocardiogram is an ultrasound of the heart that can show problems with the structure of the heart, like incorrect positioning of the two large arteries, and any irregular blood flow. An electrocardiogram (EKG), which measures the electrical activity of the heart, chest x-rays, and other medical tests may also be used to make the diagnosis.

D-TGA can also be detected with newborn pulse oximetry screening. Pulse oximetry is a simple bedside test to determine the amount of oxygen in a baby’s blood. Low levels of oxygen in the blood can be a sign of a CCHD. Newborn screening using pulse oximetry can identify some infants with a CCHD, like d-TGA, before they show any symptoms.

Treatments

Surgery is required for all babies born with d-TGA. Other procedures may be done before surgery in order to maintain, enlarge or create openings that will allow oxygen-rich blood to get out to the body.

There are two types of surgery to repair d-TGA:

- Arterial Switch Operation: This is the most common procedure and it is usually done in the first month of life. It restores usual blood flow through the heart and out to the rest of the body. During this surgery, the arteries are switched to their usual positions—the pulmonary artery arising from the right ventricle and the aorta from the left ventricle. The coronary arteries (small arteries that provide blood to the heart muscle) also must be moved and reattached to the aorta.

- Atrial Switch Operation: This procedure is less commonly performed. During this surgery, the arteries are left in place, but a tunnel (baffle) is created between the top chambers (atria) of the heart. This tunnel allows oxygen-poor blood to move from the right atrium to the left ventricle and out the pulmonary artery to the lungs. Returning oxygen-rich blood moves through the tunnel from the left atrium to the right ventricle and out the aorta to the body. Although this repair helps blood to go to the lungs and then out to the body, it also makes extra work for the right ventricle to pump blood to the entire body. Therefore, this repair can lead to difficulties later in life.

After surgery, medications may be needed to help the heart pump better, control blood pressure, help get rid of extra fluid in the body, and slow down the heart if it is beating too fast. If the heart is beating too slowly, a pacemaker can be used.

Infants who have these surgeries are not cured; they may have lifelong complications. A child or adult with d-TGA will need regular follow-up visits with a cardiologist (a heart doctor) to monitor their progress and avoid complications or other health problems. With proper treatment, most babies with d-TGA grow up to lead healthy, productive lives.

Reference

- Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111(18):1420-1435. doi:10.1002/bdr2.1589