Facts about Atrial Septal Defect

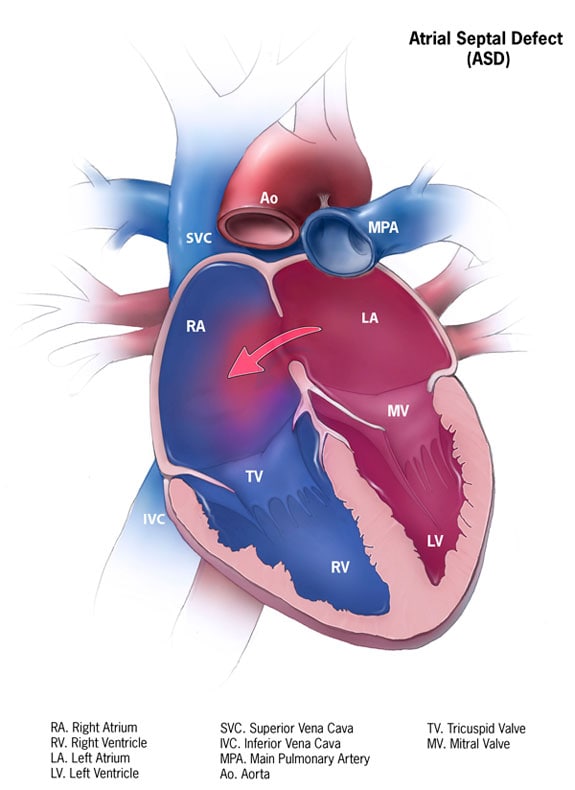

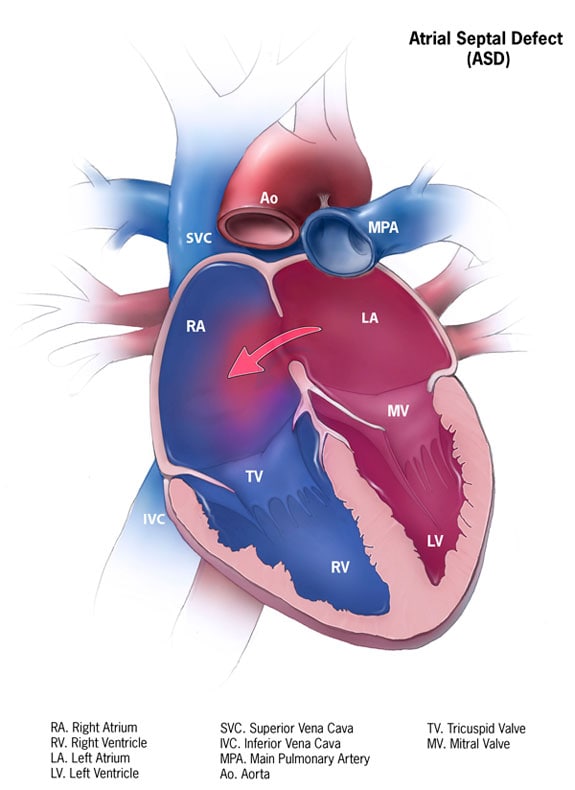

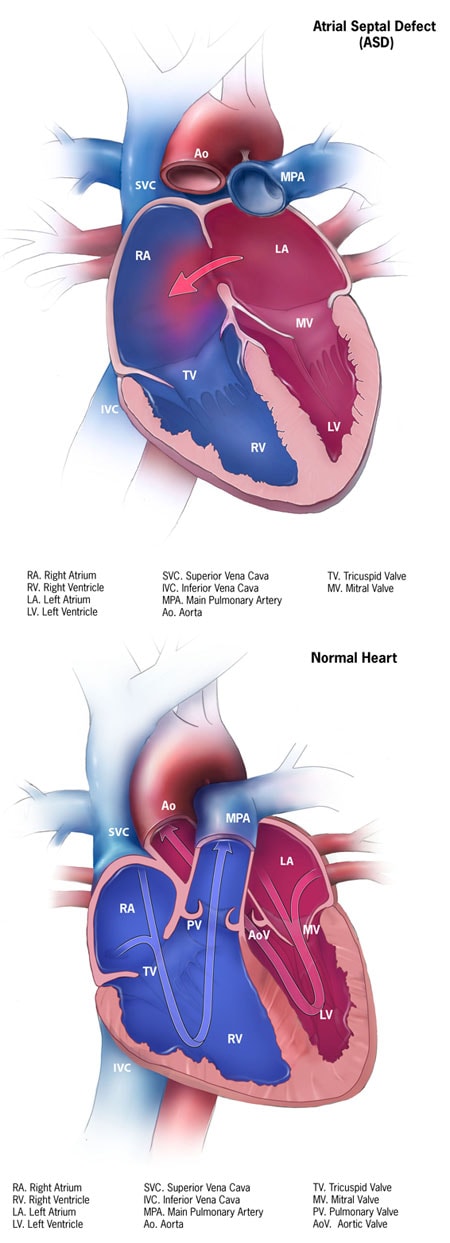

An atrial septal defect (pronounced EY-tree-uhl SEP-tuhl DEE-fekt) is a birth defect of the heart in which there is a hole in the wall (septum) that divides the upper chambers (atria) of the heart.

What is Atrial Septal Defect?

An atrial septal defect is a birth defect of the heart in which there is a hole in the wall (septum) that divides the upper chambers (atria) of the heart. A hole can vary in size and may close on its own or may require surgery. An atrial septal defect is one type of congenital heart defect. Congenital means present at birth.

As a baby’s heart develops during pregnancy, there are normally several openings in the wall dividing the upper chambers of the heart (atria). These usually close during pregnancy or shortly after birth.

If one of these openings does not close, a hole is left, and it is called an atrial septal defect. The hole increases the amount of blood that flows through the lungs and over time, it may cause damage to the blood vessels in the lungs. Damage to the blood vessels in the lungs may cause problems in adulthood, such as high blood pressure in the lungs and heart failure. Other problems may include abnormal heartbeat, and increased risk of stroke.

Learn more about how the heart works »

Occurrence

In a study in Atlanta, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 13 of every 10,000 babies born had an atrial septal defect.1 This means about 5,240 babies are born each year in the United States with an atrial septal defect. In other words, about 1 in every 769 babies born in the United States each year are born with an atrial septal defect.

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of heart defects such as atrial septal defect among most babies are unknown. Some babies have heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. These types of heart defects also are thought to be caused by a combination of genes and other risk factors, such as things the mother comes in contact with in the environment or what the mother eats or drinks or the medicines the mother uses.

Read more about CDC’s work on causes and risk factors »

Diagnosis

An atrial septal defect may be diagnosed during pregnancy or after the baby is born. In many cases, it may not be diagnosed until adulthood.

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, there are screening tests (prenatal tests) to check for birth defects and other conditions. An atrial septal defect might be seen during an ultrasound (which creates pictures of the body), but it depends on the size of the hole and its location. If an atrial septal defect is suspected, a specialist will need to confirm the diagnosis.

After the Baby is Born

An atrial septal defect is present at birth, but many babies do not have any signs or symptoms. Signs and symptoms of a large or untreated atrial septal defect may include the following:

- Frequent respiratory or lung infections

- Difficulty breathing

- Tiring when feeding (infants)

- Shortness of breath when being active or exercising

- Skipped heartbeats or a sense of feeling the heartbeat

- A heart murmur, or a whooshing sound that can be heard with a stethoscope

- Swelling of legs, feet, or stomach area

- Stroke

It is possible that an atrial septal defect might not be diagnosed until adulthood. One of the most common ways an atrial septal defect is found is by detecting a murmur when listening to a person’s heart with a stethoscope. If a murmur is heard or other signs or symptoms are present, the health care provider might request one or more tests to confirm the diagnosis. The most common test is an echocardiogram which is an ultrasound of the heart.

Treatments

Treatment for an atrial septal defect depends on the age of diagnosis, the number of or seriousness of symptoms, size of the hole, and presence of other conditions. Sometimes surgery is needed to repair the hole. Sometimes medications are prescribed to help treat symptoms. There are no known medications that can repair the hole.

If a child is diagnosed with an atrial septal defect, the health care provider may want to monitor it for a while to see if the hole closes on its own. During this period of time, the health care provider might treat symptoms with medicine. A health care provider may recommend the atrial septal defect be closed for a child with a large atrial septal defect, even if there are few symptoms, to prevent problems later in life. Closure may also be recommended for an adult who has many or severe symptoms. Closure of the hole may be done during cardiac catheterization or open-heart surgery. After these procedures, follow-up care will depend on the size of the defect, person’s age, and whether the person has other birth defects.