Mental Health Treatment Among Children Aged 5–17 Years: United States, 2021

- Key findings

- Older children were more likely than younger children to have received any mental health treatment.

- Boys were more likely than girls to have taken medication for their mental health

- The percentage of children who had received any mental health treatment was lowest among Asian non-Hispanic children.

- The percentage of children who had received any mental health treatment varied by urbanization level.

- Summary

Data from the National Health Interview Survey

- Children aged 12–17 years were more likely to have received any mental health treatment (including having taken prescription medication and received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional) in the past 12 months (18.9%) compared with children aged 5–11 years (11.3%).

- Boys were more likely than girls to have taken prescription medication for their mental health in the past 12 months (9.0% and 7.3%, respectively).

- Asian non-Hispanic children were least likely to have received any mental health treatment in the past 12 months compared with children in other race and Hispanic-origin groups.

- As the level of urbanization decreased, the percentage of children who received any mental health treatment increased.

Mental health disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and behavioral conditions, are common in school-aged children in the United States (1). Frontline treatments for mental health disorders can include medication, counseling or therapy, or both, depending on the condition and the age of the child (2). This report describes the percentage of children aged 5–17 years who have received mental health treatment in the past 12 months by selected characteristics, based on data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey. Mental health treatment is defined as having taken medication for mental health, received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, or both in the past 12 months.

Keywords: medication, counseling and therapy, National Health Interview Survey

Older children were more likely than younger children to have received any mental health treatment.

- In 2021, 14.9% of children aged 5–17 years had received any mental health treatment in the past 12 months, including 8.2% who had taken medication for their mental health and 11.5% who received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional (Figure 1).

- Older children (aged 12–17 years) were more likely than younger children (aged 5–11 years) to have received any mental health treatment (18.9% and 11.3%, respectively).

- Older children were more likely than younger children to have taken medication for their mental health (10.7% and 5.9%, respectively) and to have received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional (14.6% and 8.7%).

Figure 1. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had received any mental health treatment, taken medication for their mental health, or received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional in the past 12 months, by age group: United States, 2021

1Significantly different from children aged 12–17 years (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Children were considered to have received any mental health treatment if they were reported to have taken medication for their mental health, received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, or both in the past 12 months. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 1.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

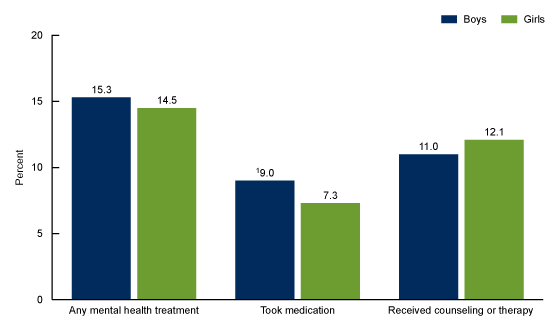

Boys were more likely than girls to have taken medication for their mental health

- An estimated 9.0% of boys were reported to have taken medication for their mental health compared with 7.3% of girls.

- In 2021, boys were as likely as girls to have received any mental health treatment in the past 12 months (15.3% and 14.5%, respectively) (Figure 2).

- No significant difference was observed in the percentage of boys and girls who had received counseling or therapy (11.0% and 12.1%, respectively).

Figure 2. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had received any mental health treatment, taken medication for their mental health, or received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional in the past 12 months, by sex: United States, 2021

1Significantly different from girls (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Children were considered to have received any mental health treatment if they were reported to have taken medication for their mental health, received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, or both in the past 12 months. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 2.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

The percentage of children who had received any mental health treatment was lowest among Asian non-Hispanic children.

- In 2021, Asian non-Hispanic children (subsequently, Asian; 4.4%) were less likely than Hispanic (10.3%), Black non-Hispanic (subsequently, Black; 12.5%), and White non-Hispanic (subsequently, White; 18.3%) children to have received any mental health treatment (Figure 3).

- Asian children were also least likely to have taken medication for their mental health (2.3%) and to have received counseling or therapy (3.1%) compared with all other race and Hispanic-origin groups.

- White children were more likely than Hispanic children to have taken medication for their mental health and were more likely than both Black and Hispanic children to have received counseling or therapy.

- Black children were more likely than Hispanic children to have taken medication for their mental health but were as likely to have received counseling or therapy.

Figure 3. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had received any mental health treatment, taken medication for their mental health, or received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional in the past 12 months, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2021

1Significantly different from Hispanic children (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from Black non-Hispanic children (p < 0.05).

3Significantly different from White non-Hispanic children (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Children were considered to have received any mental health treatment if they were reported to have taken medication for their mental health, received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, or both in the past 12 months. Children categorized as Hispanic may be of any race or combination of races. Children categorized as Asian non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, and White non-Hispanic indicated one race only. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 3.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

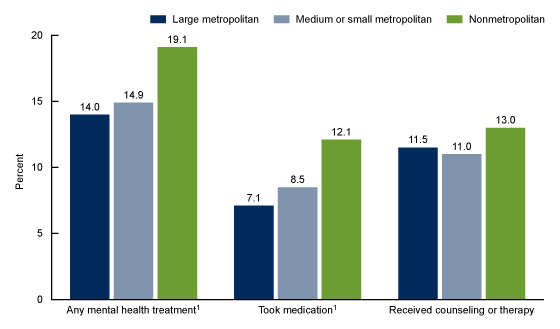

The percentage of children who had received any mental health treatment varied by urbanization level.

- In 2021, the percentage of children who had received any mental health treatment in the past 12 months increased as the place of residence became more rural, from 14.0% in large metropolitan areas to 14.9% in medium or small metropolitan areas and 19.1% in nonmetropolitan areas (Figure 4).

- The percentage of children who had taken medication for their mental health in the past 12 months also increased with rurality, from 7.1% in large metropolitan areas to 8.5% in medium or small metropolitan areas and 12.1% in nonmetropolitan areas.

- The percentage of children who received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional in the past 12 months was similar in large metropolitan (11.5%), medium or small metropolitan (11.0%), and nonmetropolitan (13.0%) areas.

Figure 4. Percentage of children aged 5–17 years who had received any mental health treatment, taken medication for their mental health, or received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional in the past 12 months, by urbanization level: United States, 2021

1Significant linear trend by urbanization level (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Children were considered to have received any mental health treatment if they were reported to have taken medication for their mental health, received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, or both in the past 12 months. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 4.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

Summary

In 2021, 14.9% of children aged 5–17 years in the United States received mental health treatment in the past 12 months. About 8% of children took prescription medication for their mental health, and 11.5% of children received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional.

Several differences in the prevalence of mental health treatment among school-aged children were consistent with a previous National Center for Health Statistics report (3) by age group, sex, race and Hispanic origin, and urbanization level. Older children (aged 12–17 years) remained more likely than younger children (aged 5–11 years) to have received any mental health treatment, and boys remained more likely than girls to have taken prescription medication for their mental health. White children remained the most likely to have received any mental health treatment, while Asian children were the least likely. The percentage of children who had taken medication for their mental health continued to increase as urbanization decreased, while the percentage of children who had received counseling or therapy did not differ by urbanization level, a finding supported in other surveillance efforts (1).

Definitions

Any mental health treatment, past 12 months: A composite measure of children who were reported to have taken medication for their mental health, received counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, or both in the past 12 months.

Race and Hispanic origin: Children categorized as non-Hispanic indicated one race only; respondents had the option to select more than one racial group. Children categorized as Hispanic may be of any race or combination of races. Estimates for non-Hispanic children of races other than Asian, Black, or White are not shown but are included in total estimates. Analyses were limited to the race and Hispanic-origin groups for which data were reliable and sufficiently powered for group comparisons.

Received therapy or counseling, past 12 months: Based on a “yes” response to the survey question, “During the past 12 months, did [child’s name] receive counseling or therapy from a mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, psychiatric nurse, or clinical social worker?”

Taking medication for mental health, past 12 months: Based on a “yes” response to the survey question, “During the past 12 months, did [child’s name] take any prescription medication to help with [his/her] emotions, concentration, behavior, or mental health?”

Urbanization level: Metropolitan size and status were determined using the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics urban–rural classification scheme for counties (4), by merging the geographic federal information processing standard codes for the county of household residence with the county-level federal information processing standard codes from the classification scheme’s data set. Large metropolitan includes large central and large fringe metropolitan counties. Medium or small metropolitan includes medium and small metropolitan counties. Nonmetropolitan includes micropolitan and noncore counties.

Data source and methods

Data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) were used for this analysis. NHIS is a nationally representative household survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. It is conducted continuously throughout the year by the National Center for Health Statistics. Interviews are typically conducted in respondents’ homes, but follow-ups to complete interviews may be conducted over the telephone. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, interviewing procedures were disrupted, and during 2021, 61.4% of Sample Child interviews were conducted at least partially by telephone (5). For more information about NHIS, visit: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

Point estimates and the corresponding confidence intervals were calculated using SAS-callable SUDAAN software (6). All estimates meet National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions (7). Linear and quadratic trends and differences between percentages were evaluated using two-sided significance tests at the 0.05 level.

About the authors

Benjamin Zablotsky and Amanda E. Ng are with the National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health Interview Statistics.

References

- Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, Black LI, Jones SE, Danielson ML, et al. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Suppl 71(2):1–42. 2022.

- Comer JS, Hong N, Poznanski B, Silva K, Wilson M. Evidence base update on the treatment of early childhood anxiety and related problems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 48(1):1–15. 2019. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1534208.

- Zablotsky B, Terlizzi EP. Mental health treatment among children aged 5–17 years: United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 381. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

- Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(166). 2014.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2021 survey description. 2022.

- RTI International. SUDAAN (Release 11.0.3) [computer software]. 2018.

- Parker JD, Talih M, Malec DJ, Beresovsky V, Carroll M, Gonzalez JF Jr, et al. National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(175). 2017.

Suggested citation

Zablotsky B, Ng AE. Mental health treatment among children aged 5–17 years: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief, no 472. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2023. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:128144.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director

Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Associate Director for Science

Division of Health Interview Statistics

Stephen J. Blumberg, Ph.D., Director

Anjel Vahratian, Ph.D., M.P.H., Associate Director for Science