Work Conditions and Serious Psychological Distress Among Working Adults Aged 18–64: United States, 2021

NCHS Data Brief No. 467, April 2023 |PDF (452 KB)

- Key findings

- What percentage of working adults experienced serious psychological distress in 2021, and did it differ by type of work shift?

- Did serious psychological distress among working adults differ by monthly variation in earnings and perceived job insecurity?

- Did differences in serious psychological distress among working adults vary by work schedule characteristics?

- Did serious psychological distress among working adults differ by having paid sick leave or working when physically ill in the past 3 months?

- Summary

Data from the National Health Interview Survey

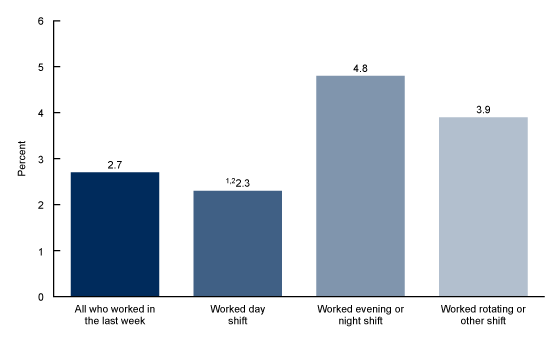

- In 2021, working adults aged 18–64 who usually worked the evening or night shift (4.8%) or a rotating shift (3.9%) were more likely to experience serious psychological distress compared with day shift workers (2.3%).

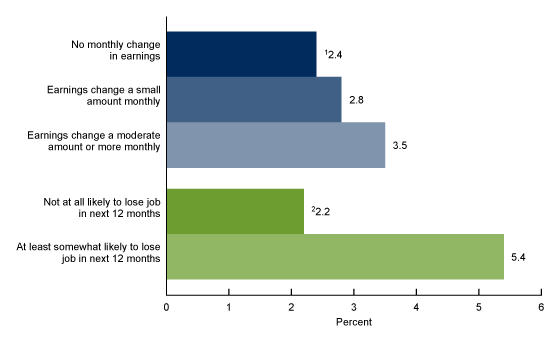

- The percentage of workers experiencing serious psychological distress increased as monthly variation in earnings increased.

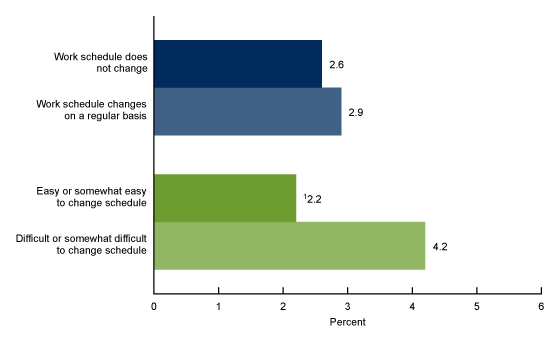

- Serious psychological distress was higher among workers who reported difficulty changing their work schedule (4.2%) compared with those who reported it was easy or somewhat easy to change their work schedule (2.2%).

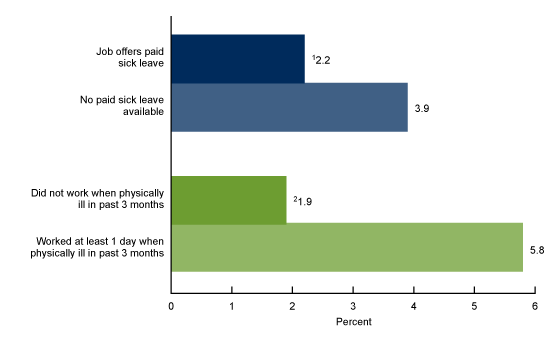

- Adults who worked when they were physically ill in the past 3 months were more likely to experience serious psychological distress (5.8%) than those who did not work when physically ill (1.9%).

Differences in work conditions such as job autonomy, job insecurity, and shift work may lead to health disparities in the population (1). Previous research has linked worse health outcomes to shift work (2–4), job insecurity (5), and other work conditions (6). This report uses 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data to examine differences in serious psychological distress in the past 30 days by work conditions, including shift work, monthly earnings variation, perceived job insecurity, and work schedule flexibility, for working adults aged 18–64 in the United States.

Keywords: working conditions, shift work, earnings volatility, job insecurity, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

What percentage of working adults experienced serious psychological distress in 2021, and did it differ by type of work shift?

- In 2021, 2.7% of working adults aged 18–64 experienced serious psychological distress (Figure 1).

- Serious psychological distress was higher among adults who usually worked the evening or night shift (4.8%) or a rotating shift (3.9%) compared with those who worked day shifts (2.3%).

Figure 1. Percentage of working adults aged 18–64 reporting serious psychological distress in the past 30 days, by type of work shift: United States, 2021

1Significantly different from those who worked evening or night shift (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from those who worked rotating or other shift (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Serious psychological distress was determined by responses to the six questions comprising the Kessler 6 nonspecific distress scale. Serious psychological distress, defined as a score of 13 or higher on the scale, includes mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate-to-serious impairment in social and occupational functioning and to require treatment. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 1.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

Did serious psychological distress among working adults differ by monthly variation in earnings and perceived job insecurity?

- The percentage of workers experiencing serious psychological distress increased as monthly variation in earnings increased (Figure 2).

- Working adults who anticipated losing their job in the next 12 months were more likely to experience serious psychological distress (5.4%) than those who did not anticipate job loss (2.2%).

Figure 2. Percentage of working adults aged 18–64 reporting serious psychological distress in the past 30 days, by variation in earnings and perceived job insecurity: United States, 2021

1Significant linear trend by monthly variation in earnings (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from at least somewhat likely to lose job in next 12 months (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Serious psychological distress was determined by responses to the six questions comprising the Kessler 6 nonspecific distress scale. Serious psychological distress, defined as a score of 13 or higher on the scale, includes mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate-to-serious impairment in social and occupational functioning and to require treatment. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 2.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

Did differences in serious psychological distress among working adults vary by work schedule characteristics?

- No statistically significant difference in serious psychological distress was observed between adults whose work schedule changed on a regular basis (2.9%) and those whose work schedule did not change (2.6%) (Figure 3).

- Serious psychological distress was higher among working adults who had difficulty changing their work schedule (4.2%) compared with those having a work schedule that was easy or somewhat easy to change (2.2%).

Figure 3. Percentage of working adults aged 18–64 reporting serious psychological distress in the past 30 days, by work schedule characteristics: United States, 2021

1Significantly different from difficult or somewhat difficult to change schedule (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Serious psychological distress was determined by responses to the six questions comprising the Kessler 6 nonspecific distress scale. Serious psychological distress, defined as a score of 13 or higher on the scale, includes mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate-to-serious impairment in social and occupational functioning and to require treatment. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 3.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

Did serious psychological distress among working adults differ by having paid sick leave or working when physically ill in the past 3 months?

- Working adults without paid sick leave (3.9%) were more likely to experience serious psychological distress than those with paid sick leave (2.2%) (Figure 4).

- Serious psychological distress was higher among working adults who worked when they were physically ill in the past 3 months (5.8%) compared with those who did not work when physically ill (1.9%).

Figure 4. Percentage of working adults aged 18–64 reporting serious psychological distress in the past 30 days, by availability of paid sick leave and report of working when physically ill: United States, 2021

1Significantly different from those who had no paid sick leave available (p < 0.05).

2Significantly different from those who worked at least 1 day when physically ill in past 3 months (p < 0.05).

NOTES: Serious psychological distress was determined by responses to the six questions comprising the Kessler 6 nonspecific distress scale. Serious psychological distress, defined as a score of 13 or higher on the scale, includes mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate-to-serious impairment in social and occupational functioning and to require treatment. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Access data table for Figure 4.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2021.

Summary

In 2021, 2.7% of working adults aged 18 to 64 overall experienced serious psychological distress. Yet rates varied by work conditions: Adults who worked night, evening, or rotating shifts were more likely to experience serious psychological distress than those working a day shift in 2021. Rates of serious psychological distress were also higher among workers who experienced month-to-month changes in their earnings or reported difficulty in changing their work schedule.

Although changes in the labor market and the nature of work in response to the COVID-19 pandemic may have affected work conditions and associations with serious psychological distress, previous research also documented disparities in health outcomes by work shift (2–4) and perceived job insecurity (5,6). This report highlights how uncertainty in work conditions—reflected by shift work, variation in earnings, job insecurity, and inflexible work schedules—is associated with serious psychological distress among working adults aged 18–64. These results suggest the role of work conditions, not just occupation and employment status, as social determinants of health (1,6).

Definitions

Serious psychological distress: Determined by responses to the six questions comprising the Kessler 6 nonspecific distress scale (7). Kessler 6 asks about the frequency of each of the six symptoms of mental illness or nonspecific psychological distress: “During the PAST 30 DAYS, how often did you feel … 1. So sad that nothing could cheer you up; 2. Nervous; 3. Restless or fidgety; 4. Hopeless; 5. That everything was an effort; and 6. Worthless.” Responses to each question are recoded as 0 (None at all) through 4 (All of the time), for a summed score ranging from 0 to 24. A value of 13 or higher defines serious psychological distress. Only respondents who answered all six questions were included in the analysis. Adults who responded “don’t know” or “refuse,” or whose responses to any of the six psychological distress questions were not certain, were excluded from the calculation. Serious psychological distress includes mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate-to-serious impairment in social and occupational functioning and to require treatment.

Working adults: Defined as sample adults aged 18–64 who indicated that they worked for pay in the week before interview, or performed seasonal or contract work in the last 12 months or were working at a family job or business not for pay. All analyses are restricted to working adults aged 18–64.

Shift work: Defined by coding responses to the question, “Which of the following best describe your usual hours of work at your most recent main job? Would you say daytime shift, evening shift, night shift, rotating shift, or some other shift?” Responses were recoded as 1 Daytime shift, 2 Evening or night shift, or 3 Rotating shift or some other shift.

Variation in earnings: Month-to-month variation in earnings was defined by coding responses to the question, “How much do/did your earnings change from month to month? Would you say not at all, a small amount, a moderate amount, or a large amount?” Responses were recoded as 0 No change in monthly earnings, 1 Small change in monthly earnings, or 2 Moderate or large change in monthly earnings.

Perceived job insecurity: Defined by coding responses to the question, “Thinking about the next 12 months, how likely do you think it is that you will lose your job or be laid off? Would you say very likely, fairly likely, somewhat likely, or not at all likely?” Responses were recoded as 0 Not at all likely to lose job in next 12 months or 1 At least somewhat likely to lose job in next 12 months.

Variation in work schedule: Defined by coding responses to the question, “Does/did your work schedule at your main job change on a regular basis?” Responses were recoded as 0 Work schedule does/did not change at all or 1 Work schedule changes/changed on a regular basis.

Work schedule flexibility: Defined by coding responses to the question, “How easy or difficult is/was it for you to change your work schedule to do things that are important to you or your family? Would you say very easy, somewhat easy, somewhat difficult, or very difficult?” Responses were recoded as 0 Easy/Somewhat easy to change work schedule or 1 Difficult/Somewhat difficult to change work schedule.

Availability of paid sick leave: Defined by coding responses to the question, “Was/is paid sick leave available if you need it?” Responses were recoded as 0 Job does/did not offer paid sick leave or 1 Job offers/offered paid sick leave.

Days worked when physically ill: Defined by coding responses to the question, “During the past 3 months, how many days did you work while you were physically ill?” Responses were recoded as 0 Did not work any days when physically ill in the past 3 months or 1 Worked at least 1 day when physically ill in the past 3 months.

Data source and methods

Data from the 2021 NHIS were used for this analysis. NHIS is a nationally representative household survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population that is conducted continuously throughout the year by the National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS interviews are typically conducted in respondents’ homes, but follow-ups to complete interviews may be conducted over the telephone. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, interviewing procedures were disrupted, and during 2021, 62.8% of Sample Adult interviews were conducted at least partially by telephone (8). For more information about NHIS, visit: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

Point estimates and corresponding confidence intervals for this analysis were calculated using Stata version 16 software (9) to account for the complex sample design of NHIS. Differences between percentages were evaluated using two-sided significance tests at the 0.05 level. All estimates meet standards of reliability specified in “National Center for Health Statistics Data Presentation Standards for Proportions” (10).

About the author

Laryssa Mykyta is with the National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Analysis and Epidemiology.

References

- Ahonen EQ, Fujishiro K, Cunningham T, Flynn M. Work as an inclusive part of population health inequities research and prevention. Am J Pub Health 108(3):306–11. 2018.

- Zhao Y, Richardson A, Poyser C, Butterworth P, Strazdins L, Leach LS. Shift work and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 9(6)2:763–93. 2019.

- Torquati L, Mielke GI, Brown WJ, Burton NW, Kolbe-Alexander TL. Shift work and poor mental health: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Am J Pub Health 109(11):e13–e20. 2019.

- Yang X, Di W, Zeng Y, Liu D, Han M, Qie R, et al. Association between shift work and risk of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 31(10):2792–9. 2021.

- Burgard SA, Brand JE, House JS. Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Soc Sci Med 69(5):777–85. 2009.

- Burgard, SA, Lin KY. Bad jobs, bad health? How work and working conditions contribute to health disparities. Am Behav Sci 57(8):10.1177/0002764213487347. 2013.

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(2):184–9. 2003.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey 2021 survey description. 2022.

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software (Release 16) [computer software]. 2019.

- Parker JD, Talih M, Malec DJ, Beresovsky V, Carroll M, Gonzalez JF Jr, et al. National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(175). 2017.

Suggested citation

Mykyta L. Work conditions and serious psychological distress among working adults aged 18–64: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief, no 467. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2023: DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:126566.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director

Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Associate Director for Science

Division of Analysis and Epidemiology

Irma E. Arispe, Ph.D., Director

Julie D. Weeks, Ph.D., Acting Associate Director for Science