Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Surveillance for Travel-Related Disease — GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997–2011

Corresponding author: Kira Harvey, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Disease, CDC. Telephone: 404-639-7717; E-mail: jii3@cdc.gov.

Abstract

Problem/Condition: In 2012, the number of international tourist arrivals worldwide was projected to reach a new high of 1 billion arrivals, a 48% increase from 674 million arrivals in 2000. International travel also is increasing among U.S. residents. In 2009, U.S. residents made approximately 61 million trips outside the country, a 5% increase from 1999. Travel-related morbidity can occur during or after travel. Worldwide, 8% of travelers from industrialized to developing countries report becoming ill enough to seek health care during or after travel. Travelers have contributed to the global spread of infectious diseases, including novel and emerging pathogens. Therefore, surveillance of travel-related morbidity is an essential component of global public health surveillance and will be of greater importance as international travel increases worldwide.

Reporting Period: September 1997–December 2011.

Description of System: GeoSentinel is a clinic-based global surveillance system that tracks infectious diseases and other adverse health outcomes in returned travelers, foreign visitors, and immigrants. GeoSentinel comprises 54 travel/tropical medicine clinics worldwide that electronically submit demographic, travel, and clinical diagnosis data for all patients evaluated for an illness or other health condition that is presumed to be related to international travel. Clinical information is collected by physicians with expertise or experience in travel/tropical medicine. Data collected at all sites are entered electronically into a database, which is housed at and maintained by CDC. The GeoSentinel network membership program comprises 235 additional clinics in 40 countries on six continents. Although these network members do not report surveillance data systematically, they can report unusual or concerning diagnoses in travelers and might be asked to perform enhanced surveillance in response to specific health events or concerns.

Results: During September 1997–December 2011, data were collected on 141,789 patients with confirmed or probable travel-related diagnoses. Of these, 23,006 (16%) patients were evaluated in the United States, 10,032 (44%) of whom were evaluated after returning from travel outside of the United States (i.e., after-travel patients). Of the 10,032 after-travel patients, 4,977 (50%) were female, 4,856 (48%) were male, and 199 (2%) did not report sex; the median age was 34 years. Most were evaluated in outpatient settings (84%), were born in the United States (76%), and reported current U.S. residence (99%). The most common reasons for travel were tourism (38%), missionary/volunteer/research/aid work (24%), visiting friends and relatives (17%), and business (15%). The most common regions of exposure were Sub-Saharan Africa (23%), Central America (15%), and South America (12%). Fewer than half (44%) reported having had a pretravel visit with a health-care provider.

Of the 13,059 diagnoses among the 10,032 after-travel patients, the most common diagnoses were acute unspecified diarrhea (8%), acute bacterial diarrhea (5%), postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (5%), giardiasis (3%), and chronic unknown diarrhea (3%). The most common diagnostic groupings were acute diarrhea (22%), nondiarrheal gastrointestinal (15%), febrile/systemic illness (14%), and dermatologic (12%). Among 1,802 patients with febrile/systemic illness diagnoses, the most common diagnosis was Plasmodium falciparum malaria (19%).

The rapid communication component of the GeoSentinel network has allowed prompt responses to important health events affecting travelers; during 2010 and 2011, the notification capability of the GeoSentinel network was used in the identification and public health response to East African trypanosomiasis in Eastern Zambia and North Central Zimbabwe, P. vivax malaria in Greece, and muscular sarcocystosis on Tioman Island, Malaysia.

Interpretation: The GeoSentinel Global Surveillance System is the largest repository of provider-based data on travel-related illness. Among ill travelers evaluated in U.S. GeoSentinel sites after returning from international travel, gastrointestinal diagnoses were most frequent, suggesting that U.S. travelers might be exposed to unsafe food and water while traveling internationally. The most common febrile/systemic diagnosis was P. falciparum malaria, suggesting that some U.S. travelers to malarial areas are not receiving or using proper malaria chemoprophylaxis or mosquito-bite avoidance measures. The finding that fewer than half of all patients reported having made a pretravel visit with a health-care provider indicates that a substantial portion of U.S. travelers might not be following CDC travelers' health recommendations for international travel.

Public Health Action: GeoSentinel surveillance data have helped researchers define an evidence base for travel medicine that has informed travelers' health guidelines and the medical evaluation of ill international travelers. These data suggest that persons traveling internationally from the United States to developing countries remain at risk for illness. Health-care providers should help prepare travelers properly for safe travel and provide destination-specific medical evaluation of returning ill travelers. Training for health-care providers should focus on preventing and treating a variety of travel-related conditions, particularly traveler's diarrhea and malaria.

Introduction

Since the advent of modern commercial aviation in the 1950s, international civilian travel has increased steadily to record levels (1). In 2012, the number of international tourist arrivals worldwide was projected to reach a new high of 1 billion arrivals, a 48% increase from 674 million arrivals in 2000. Tourist destinations also have become increasingly diverse, with the proportion of international tourist arrivals in countries with emerging and developing economies increasing from 31% in 1990 to 47% in 2010. Tourism comprises approximately 5% of the total worldwide gross domestic product, and its contribution to many emerging economies is likely to be substantially higher (1).

International travel also is increasing among U.S. residents. In 2009, U.S. residents made 61 million overnight trips outside the country, representing a 5% increase from 1999 (2). This increase reflects not only traditional tourism but also travel for other purposes. For example, 14% of U.S. students pursuing a bachelor's degree study abroad at least once, and, for the 2010–2011 school year, 46% of these students studied in places outside Europe (3). In 2011, of 27,023,000 U.S. residents traveling overseas, 35% listed visiting friends and/or family as their main purpose of travel (4). This includes immigrants and their children who return to their country of origin to visit friends and relatives (VFR travelers). U.S. residents also devote considerable resources to international travel and collectively spent $79.1 billion on international tourism in 2011. This expenditure represented 7.7% of the world's international tourism market, making the United States second only to Germany in terms of the international tourism market share (1).

International travelers can experience travel-related morbidity during and after travel. Of the approximately 50 million persons who travel from industrialized countries to developing countries each year, 8% report becoming ill enough to seek health care either during or after travel (5,6). Many other travelers also experience health problems that often go unreported (6,7). First- and second-generation immigrant VFR travelers are thought to experience a greater burden of travel-related disease than other types of travelers (8,9).

Travelers can contribute to the global spread of infectious diseases, including novel and emerging pathogens. In 2003, during the initial phase of the global epidemic of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), an infected professor from southern China traveled to a major international hotel in Hong Kong, where he infected others. Persons infected with SARS subsequently traveled to other countries, leading to rapid worldwide spread of the disease (10). More recently, international travelers infected with novel H1N1 influenza played a major role in the rapid global spread of the virus (11). Travelers also have carried pathogens to areas of the world where these pathogens were rare or had been eliminated. Recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles (12) and mumps (13) in the United States have been traced to contact with persons who had traveled to locations where vaccination was less prevalent. In addition, travel and migration have contributed to recent introduction or reintroduction of vectorborne diseases in places that had been free from these diseases, such as locally acquired dengue in Florida (14) and malaria in Greece (15) and in Great Exuma Island in the Caribbean (16).

Description and evaluation of the patterns of disease among persons traveling internationally can provide information that might help prevent, treat, and control disease among international travelers and help prevent the global spread of pathogens. The timely detection of diseases in this population can alert the public health and medical communities to disease outbreaks before they spread to or become apparent in the general population.

The GeoSentinel Surveillance System (GeoSentinel) was established in 1995 to perform provider-based monitoring of travel-related morbidity among persons traveling internationally. The goals of GeoSentinel are to 1) improve the understanding of morbidity and disease acquisition among international travelers, and immigrants; 2) expand the evidence-base that guides pretravel health recommendations and the evaluation and medical management of the ill traveler; 3) enhance the detection of important health events occurring among this mobile population; and 4) create a communications network that allows rapid dissemination of important health information among medical practitioners, government bodies, and the public. GeoSentinel clinics worldwide collect demographic, travel, and clinical diagnosis surveillance data systematically from ill international travelers both during and after travel, using the best reference diagnostic methods available in their practice settings. Additional information on GeoSentinel and site locations is available at http://www.istm.org/Default.aspx.

This report describes the GeoSentinel surveillance system, documents its growth and evolution during 1995–2011, provides summary data from 22 U.S. sites that participated in the GeoSentinel network at any point during September 1997–December 2011 (the most recent year for which finalized data are available), and describes selected important health events in the worldwide GeoSentinel population during 2010–2011. The findings presented in this report will inform providers and public health agencies about the travel-related illnesses that are most commonly seen in returned travelers in the United States, which will help providers prepare travelers properly for safe international travel and also provide guidance for the evaluation and treatment of ill patients who seek medical care after travel.

The GeoSentinel Surveillance System

Establishment of GeoSentinel

In 1995, three members* of the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) proposed a framework for GeoSentinel, a global provider-based surveillance system focused on patients evaluated at travel and tropical medicine clinics. Later that year, a working group of nine U.S.-based ISTM member travel clinics formally established GeoSentinel (17). At that time, approximately one third of ISTM clinics reported seeing more than 100 post-travel patients per year, and no systems were in place to compile patient data from these geographically dispersed small clinics (18). GeoSentinel was established to fill the need for a collaborative clinic-based global surveillance system designed to collect limited de-identified demographic, travel, and clinical data from returned international travelers, immigrants, and foreign visitors who visit clinics for evaluation of illnesses suspected to be related to travel (17).

These data, which can link place of acquisition of illness to time of exposure, can be used both to monitor disease burden and distribution and to detect the emergence of new human infections or new patterns of disease occurrence or transmission. In addition, by linking travel medicine clinics around the world, GeoSentinel can facilitate rapid communication of important information among medical practitioners, governmental bodies, and the public (17). By 1996, GeoSentinel had become organized as a cooperative effort between ISTM and CDC, and systematic data collection began in 1997.

GeoSentinel Sites

GeoSentinel sites are specialized travel/tropical medicine units; the GeoSentinel site director and a majority of contributing physicians have documented training and expertise in travel/tropical medicine and/or significant experience in the care of patients with travel-related or tropical diseases. Most sites are located within academic health centers (19). GeoSentinel sites are asked to submit completed reporting forms (Appendix A) for all patients evaluated for an illness or other health condition that is presumed to be travel-related.

After its inception, the number of sites in GeoSentinel increased steadily from the initial nine U.S. sites, with several European clinics being added during the first 2 years after data collection began. By 1999, GeoSentinel comprised an international network of 24 travel/tropical medicine clinics, 14 (58%) of which were located in the United States. During 2004–2005, in response to the increased concern for potential emerging diseases following the SARS epidemic, GeoSentinel received supplemental CDC funding to establish additional sites in Asia and elsewhere. These sites are known to treat a substantial number of travelers and expatriates who become ill and seek care while traveling. As of December 2011, the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance System comprised 54 member travel/tropical medicine clinics in 24 countries on six continents (Figure 1), including 17 (31%) sites in the United States.

Network Members

In October 2001, the GeoSentinel Network expanded to include additional travel/tropical medicine providers who do not enter data from patient records into the GeoSentinel database. However, Network members can report noteworthy diagnoses in travelers and, along with the GeoSentinel clinic sites, might be asked to perform enhanced surveillance in response to important health events or concerns.

Network members also receive electronic mail from GeoSentinel, individual sites, and other Network members alerting them to unusual or noteworthy health events among travelers. Such alerts allow rapid linkage of and communication among a substantial number of clinics and health authorities around the world. This rapid communication infrastructure enables timely outbreak identification and response. As of April 2011, a total of 235 clinics in 40 countries on six continents were members of the GeoSentinel Network (Figure 1).

Variables and Definitions

GeoSentinel is limited to data concerning patients evaluated by medical providers at GeoSentinel clinics. Travelers must have crossed an international border within 10 years of clinic visit and have sought medical care for a presumed travel-related illness. Data from patients evaluated for other reasons within that 10-year timeframe and ultimately determined to have a travel-related illness also can be included. For each patient, GeoSentinel uses a form to collect 28 data elements pertaining to patient demographic information, travel history, presenting symptoms, and clinical diagnoses (Appendix A). The following definitions of variables are used:

Reason for travel: The main reason for travel related to the current illness; limited to a single designation (Box 1).

Expatriate: A person living in a destination country with a permanent residence and address and using mostly the infrastructure used by local residents, independent of travel duration.

Patient type: This includes classifications regarding whether the patient was evaluated in person, and whether that patient was an inpatient or an outpatient.

- Inpatient: The patient was seen at the reporting GeoSentinel site as an inpatient.

- Outpatient: The patient was seen at the reporting GeoSentinel site as an outpatient.

- Tele-consult in-patient: The patient's record was obtained after a doctor at the reporting GeoSentinel site provided a telephonic consultation regarding an inpatient at a different location.

- Tele-consult outpatient: The patient's record was obtained after a doctor at the recording GeoSentinel site provided a telephonic consultation regarding an outpatient at a different location.

Clinical setting: The timing of the clinic visit in relation to travel.

- During travel: The clinic visit occurred before the trip ended. Includes expatriates evaluated in the country of their expatriation for illnesses that most likely were acquired in that country or for which the country of exposure could not be ascertained.

- After travel: The clinic visit occurred after the trip ended. Includes expatriates with illnesses that most likely were acquired outside the country of their expatriation.

- Immigration-only travel: The clinic visit occurred after the primary immigration trip to the country of the reporting site, and the diagnosis is for an illness most likely acquired before immigration.

Travel-related: Designates the relation of the main diagnosis to the patient's travel.

- Travel-related: Used when the illness under evaluation, initially suspected to be travel-related, was determined to have been acquired during the patient's travel.

- Not travel-related: Used when the illness under evaluation, initially suspected to be travel related, was determined to have been acquired before departure from or after returning to the home country.

- Not ascertainable: Used when the illness under evaluation, initially suspected to be travel related, was equally likely to have been acquired during the patient's travel or before departing from or after returning to the residence country.

Diagnosis and diagnosis type: Medical providers or coders choose from approximately 500 widely varied diagnoses determined by CDC-ISTM consensus, each of which is classified as either etiologic or syndromic. A write-in option is available for diagnoses not included on the list. The diagnosis list has evolved to reflect the changing needs of the network (Appendix B) (20).

- Etiologic: This diagnosis type reflects specific disease etiologies (e.g., malaria or Plasmodium falciparum). The "diagnosis status" of etiologic diagnoses might be confirmed, probable, or suspect (see Diagnosis status).

- Syndromic: This diagnosis type reflects symptom- or syndrome-based etiologies (e.g., gastroenteritis) when a more specific etiology is not known or could not be determined as a result of use of empiric therapy, self-limited disease, or inability to justify additional diagnostic tests beyond standard clinical practice. The "diagnosis status" of all syndromic diagnoses is "confirmed" (see Diagnosis status).

Diagnosis status: The strength of the diagnosis is categorized in one of three ways:

- Confirmed: Diagnosis has been made by an indisputable clinical finding or diagnostic test. "Syndromic" diagnoses are always considered to be "confirmed."

- Probable: Diagnosis is supported by evidence strong enough to establish presumption but not proof.

- Suspect: Diagnosis warrants consideration on the basis of a clinical finding or laboratory result.

Syndrome/System groupings of diagnoses: All GeoSentinel diagnoses are categorized into groups (Box 2).

Main presenting symptom: The predefined grouping is used to categorize the patient's main presenting symptom(s). As many symptom groups as are required can be coded for each patient. Patients without symptoms can be included in one of the following two groupings.

- Screening: The patient underwent risk-based screening for a travel-related disease.

- Abnormal laboratory test: The patient was referred to the GeoSentinel site because an abnormal result was found on a laboratory test that was performed elsewhere.

Data Collection

Initially, following the development of a standard data collection form in 1997, GeoSentinel used a paper-based data collection system. Sites completed a form for each patient with an illness presumed to be travel-related. Completed forms were then sent to CDC for the information to be entered into the database.

In April 2001, sites began using a web-based data submission system as they gained access to the requisite technology. The web-based data submission system contains the same fields as the paper data collection forms. In 2002, all sites were given the option of submitting data using the web-based data submission system. All sites were formally offered access to the web-based data submission system in June 2002. By September 2002, the web-based data submission system was being used by 10 of 32 sites. Also beginning in 2002, stepwise improvements to the data entry website were made to reduce the number of data entry errors and expand data functionality (Box 3).

In May 2007, a second-generation web-based data entry application was introduced. By this time, all 32 GeoSentinel sites were providing patient data via the Internet. The second-generation data-entry application featured a complete redesign of both the data entry application and the database. An improved user interface included internal validation, which prevented entry of contradictory data.

Methods

This report summarizes data from patients with at least one final travel-related diagnosis who were evaluated at the 22 current and past GeoSentinel sites located in the United States during September 1997–December 2011. These 22 sites did not necessarily submit data every year of the reporting period. Patients must have been evaluated within 10 years of returning from a trip outside of the United States. The final travel-related diagnosis must have been classified as probable or confirmed. Only patients who were evaluated in a clinical setting (i.e., the timing of clinic visit in relation to travel) that was classified as after-travel were included in this analysis. Patients evaluated in a clinical setting classified as during travel or immigration only were excluded from the analysis. No restriction was placed on resident status (i.e., data from both U.S. and non-U.S. resident patients were included).

Analysis

This report presents the results of a descriptive analysis from data collected at the 22 current and past GeoSentinel sites located in the United States. No statistical tests of significance were performed. Frequencies were calculated for the following after-travel patient characteristics: sex, age group (<19, 19–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years), patient type (i.e., inpatient or outpatient status), birth country (United States versus non–United States), country of residence (United States versus non–United States), reason for travel (Box 1) or expatriate status, pretravel encounter, and region of exposure. Region of exposure was calculated on the basis of the most likely country or countries of exposure (limited to two countries). If two countries in different regions were listed as country of exposure, then the region of exposure was not listed. Frequencies of final travel-related diagnoses and syndrome/system groupings of diagnoses also were determined (Appendix B). Patients could have one or more than one final travel-related diagnosis. For the top three regions of travel, the top two diagnoses by region also were determined. The region of exposure for current illness was assigned by using modified UNICEF groupings (Figure 2). For all frequency calculations, records with unknown or missing data were included in each denominator. Analyses were conducted by using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Selected Worldwide Health Event Notifications

To illustrate the notification capability of the GeoSentinel Network, three examples of important health events occurring during 2010 and 2011 are described. These health events were not limited to U.S. sites and included patients seen elsewhere in the global network.

Results

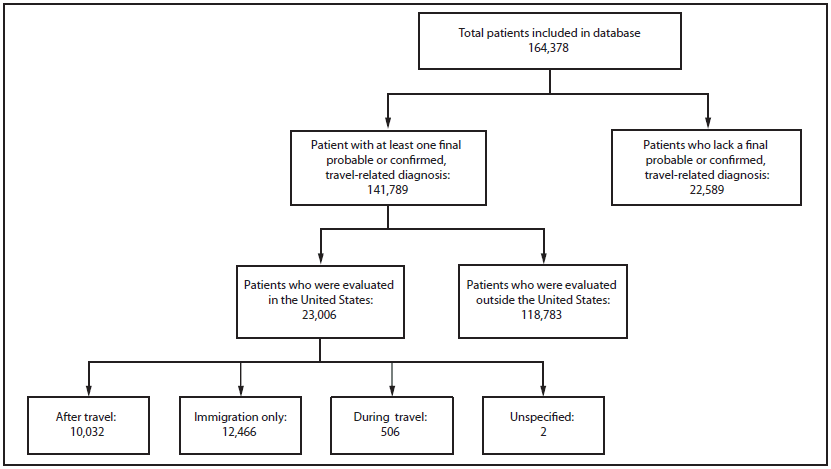

During September 1997–December 2011, a total of 164,378 patients were evaluated at GeoSentinel sites worldwide (U.S. and non-U.S.) and included in the GeoSentinel Surveillance System's database. Of these, 141,789 (86%) received at least one final confirmed or probable travel-related diagnosis; 23,006 (16%) were reported from 22 current and past GeoSentinel sites in the United States. Included in this analysis were 10,032 after-travel patients (Figure 3), with 13,059 confirmed or probable final diagnoses (1.3 diagnoses per patient).

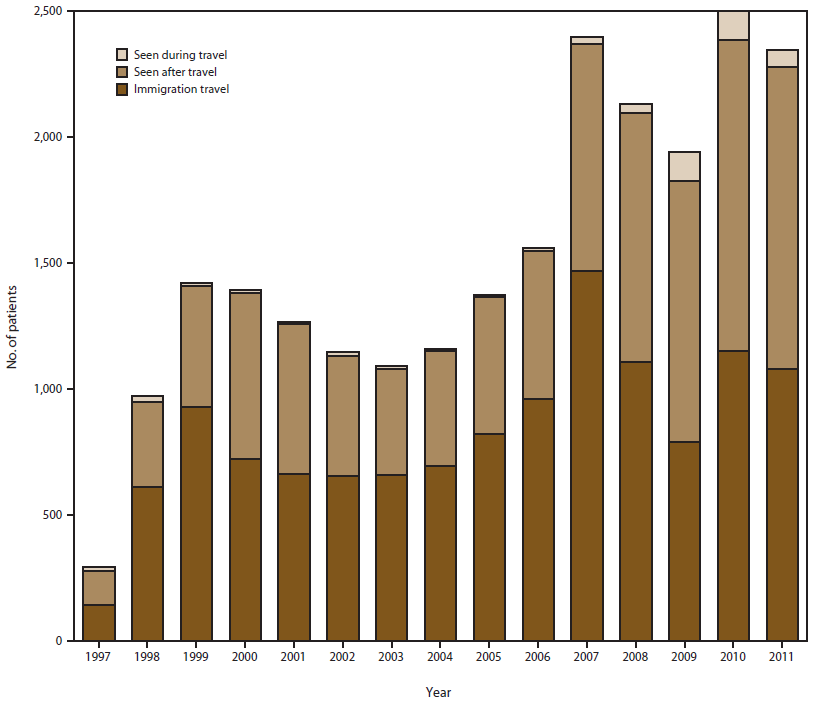

During September 1997–December 2011, the number of patients evaluated at U.S. GeoSentinel sites and included in the GeoSentinel database per year increased, as has the proportion of all patients evaluated after travel (Figure 4). During 1998, a total of 971 patients were seen at U.S. GeoSentinel sites and included in the GeoSentinel database, 333 (34%) of whom were patients evaluated after travel. In 2011, a total of 2,344 patients were evaluated at U.S. GeoSentinel sites and included in the GeoSentinel database, 1,199 (51%) of whom were patients evaluated after travel.

After-Travel Patients from U.S. GeoSentinel Sites

Of the 10,032 after-travel patients who were evaluated at U.S. GeoSentinel sites during September 1997–December 2011 and who received a diagnosis, a total of 4,977 (50%) were female and 4,856 number (48%) were male; sex was not reported for 199 (2%) patients. The median age was 34 years. By age group, 735 (7%) were aged <19 years, 4,398 (44%) were aged 19–34 years, 2,343 (23%) were aged 35–49 years, 1,850 (18%) were aged 50–64 years, and 622 (6%) were aged ≥65 years (Table 1). Most (84%) patients were evaluated in an outpatient setting. More than three fourths (76%) of patients were born in the United States, and nearly all (99%) were current U.S. residents.

The most common reason for travel among the after-travel patients who received a diagnosis was tourism (38%); other reasons for travel included being a missionary/volunteer/researcher/aid worker (24%), a VFR traveler (17%), a business person (15%), a student (6%), a member of the military (<1%), and a medical tourist (<1%). Approximately 12% of patients were expatriates. Fewer than half of all patients (44%) reported consulting a medical provider before traveling in preparation for their international trip.

The most common region of exposure was Sub-Saharan Africa (23%). Other common regions of exposure included Central America (15%), South America (12%), the Caribbean (9%), South Central Asia (8%), and South East Asia (7%). Less common regions of exposure included Western Europe (5%), North East Asia (3%), the Middle East (2%), North Africa (2%), Eastern Europe (1%), Oceania (1%), North America (<1%), and Australia/New Zealand (<1%). Region of exposure could not be determined or was not reported for 11% of patients (Table 1).

Diagnoses

Of the 13,059 diagnoses included in analysis, the most common were acute unspecified diarrhea (8%), acute bacterial diarrhea (5%), postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (5%), giardia (3%), chronic unknown diarrhea (3%), P. falciparum malaria (3%), viral syndrome without rash (2%), simple intestinal strongyloides (2%), blastocystis (2%), and upper respiratory tract infection (2%) (Table 2). Eighty-four percent of specific diagnoses fell into eight syndromic groupings: acute diarrhea (22%), other gastrointestinal (15%), febrile/systemic disease (14%), dermatologic (12%), chronic diarrhea (8%), respiratory (8%), and nonspecific signs and symptoms (5%) (Table 3).

Of the 2,811 diagnoses in the acute diarrhea grouping, 80% were accounted for by five diagnoses: acute unspecified diarrhea (36%), acute bacterial diarrhea (23%), giardia (13%), amoebas (4%), and campylobacter (4%). Of the 1,908 diagnoses in the other gastrointestinal grouping, five diagnoses comprised 48%: simple intestinal strongyloides (15%), blastocystis (15%), abdominal pain (6%), esophagitis (6%), and Helicobacter pylori-positive gastritis (6%). Among the 1,100 diagnoses in the chronic diarrhea grouping, 95% were accounted for by five diagnoses: postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (55%), chronic unknown diarrhea (32%), irritable bowel syndrome (4%), ulcerative colitis (3%), and postinfectious lactose intolerance (1%).

Of the 1,802 diagnoses in the febrile/systemic disease grouping, 59% were accounted for by five diagnoses: P. falciparum malaria (19%), viral syndrome without rash (17%), uncomplicated dengue (11%), unspecified febrile disease (<3 weeks) (8%), and Epstein-Barr virus (4%). In the respiratory grouping, 70% of 1,002 diagnoses were accounted for by five diagnoses: upper respiratory tract infection (27%), acute bronchitis (18%), acute sinusitis (11%), bacterial pneumonia (lobar) (8%), and asthma (6%). In the dermatologic grouping, 44% of 1,596 were accounted for by five diagnoses: insect bite/sting (15%), nonfebrile rash of unknown etiology (10%), fungal infection (superficial/cutaneous mycosis) (7%), cutaneous leishmaniasis (6%), and skin and soft tissue infection (6%). In the nonspecific symptoms grouping, 72% of 702 diagnoses were accounted for by eosinophilia (28%), fatigue for at least 1 month (nonfebrile) (18%), fatigue for <1 month (nonfebrile) (14%), anemia (8%), and weight loss (4%).

Of 3,069 diagnoses among patients exposed to their illnesses in Sub-Saharan Africa, the most frequent were P. falciparum malaria (10%) and acute unspecified diarrhea (6%). Over half (58%) of P. falciparum malaria diagnoses among patients exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa occurred among VFR travelers, and 6% of acute unspecified diarrhea diagnoses in this group occurred among VFR travelers. Of the 1,977 diagnoses among patients exposed in Central America, the most frequent were acute unspecified diarrhea (13%) and acute bacterial diarrhea (6%). Of the 1,562 diagnoses among patients exposed in South America, the most frequent were acute unspecified diarrhea (8%) and postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (7%). Of the 1,186 diagnoses among patients exposed in the Caribbean, the most frequent were acute unspecified diarrhea (6%) and acute bacterial diarrhea (5%).

Selected Health Event Notifications in GeoSentinel, 2010–2011

The GeoSentinel network is designed to allow rapid communication about important health events among travelers. This enhanced communication has allowed prompt outbreak response from CDC and other clinical and public health entities worldwide. Three recent important health events exemplify the notification capability of GeoSentinel.

Event 1: East African Trypanosomiasis in Eastern Zambia and North Central Zimbabwe

In late August 2010, a GeoSentinel site in the United States reported a male patient with Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (East African trypanosomiasis [EAT]). This patient was a hunter who had traveled recently to Zambia. The site later confirmed that less than 2 weeks prior to visiting a GeoSentinel site, the patient had traveled to a game reserve in the South Luangwa River Valley, where he was bitten by tsetse flies. This situation was unusual because no instances of EAT among international travelers to Zambia had been reported since 2000 (21), and the last reported occurrence of a U.S. traveler with EAT acquired in Zambia occurred in 1986 (22).

During October 21–November 21, 2010, three additional patients who were evaluated at three other GeoSentinel sites received a diagnosis of EAT. All three reported travel to the South Luangwa River Valley region in Zambia or the neighboring Mana Pools region in northern Zimbabwe. These patients and additional patients exposed in the same region but not identified through the GeoSentinel Network have been reported elsewhere (23,24).

On November 11, 2010, a GeoSentinel project director sent all sites and network members an alert describing the EAT occurrences and recommending that clinicians consider EAT as a diagnosis in travelers returning from Eastern Zambia and North Central Zimbabwe. In March 2012, CDC's Travelers' Health Branch posted a travel notice advising travelers to parts of East Africa to avoid tsetse fly bites and to watch for symptoms of EAT if they are bitten.

Event 2: Plasmodium vivax malaria in Greece

In August 2011, a GeoSentinel network member in Romania reported to a GeoSentinel Project Director about a patient with Plasmodium vivax malaria whose only recent travel was to the Skala and Elos regions of Greece (25). Although malaria was eradicated officially in Greece in 1974, subsequent instances of autochthonous (introduced) transmission of imported malaria to local residents in this region have been reported (15). Before this event, the most recent reported occurrences of malaria in travelers to Greece were in 2000 in a German couple with a history of travel to Kassandra, which is located in Chalkidiki (26). On August 19, 2011, a GeoSentinel project director alerted all GeoSentinel sites and network members of this event and asked them to be aware of these events when preparing travelers to and evaluating febrile travelers from the Skala and Elos regions of Greece. The Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention later published a report about 20 nontraveling Greeks who developed P. vivax malaria between May and September of 2011 (27). Recognition of this occurrence ultimately informed CDC malaria guidelines for travelers to Greece.

Event 3: Muscular sarcocystosis on Tioman Island, Malaysia

On October 25, 2011, a GeoSentinel site in Munich reported seven ill German travelers with fever, significant muscle pain, eosinophilia, and elevated serum creatinine phosphokinase. All seven travelers tested negative for both trichinosis and toxoplasmosis, and all had vacationed on islands off the east coast of peninsular Malaysia during the previous summer. A muscle biopsy from one of the patients revealed a single intracellular structure consistent with muscular sarcocystosis, a rarely reported disease caused by infection with Sarcocystis species. By October 27, 2011, as a result of a series of notifications to the GeoSentinel network, nine GeoSentinel sites and one non-GeoSentinel clinic in Europe, Asia, and North America had reported that 23 patients had been evaluated with similar symptoms; all had traveled to Tioman Island, Malaysia. On October 31, 2011, these patients were reported on ProMED-mail (28). By November 30, 2011, a total of 32 patients with suspected sarcocystosis had been reported to GeoSentinel (29).

On November 17, 2011, with assistance from EuroTravNet † and CDC and with support from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and TropNet,§ GeoSentinel launched an investigation to describe the demographic, travel, and clinical characteristics of these patients and to identify a possible common source of exposure on Tioman Island. On December 6, 2011, CDC's Travelers' Health Branch posted an outbreak notice for sarcocystosis in Malaysia, which included recommendations for safe food and water consumption and proper hygiene. On January 20, 2012, CDC published preliminary information on the outbreak (29). GeoSentinel sites continue to be alert to identify sarcocystis in patients returning from Malaysia.

Discussion

GeoSentinel is a clinic-based global surveillance system that tracks infectious diseases and other adverse health outcomes in returned travelers, foreign visitors, and immigrants. This system supplements traditional laboratory-based surveillance by focusing on the collection of data from a specific mobile population and linking data from clinics around the world. The collected data reflect a broad spectrum of etiologic and syndromic tropical and travel-related diseases, and documents the time and place of disease acquisition. Before the establishment of GeoSentinel, no system was in place to compile disease data on this population. GeoSentinel monitors disease among international travelers and can detect emergence of novel or re-emergent pathogens or changing patterns of transmission or acquisition of known diseases. GeoSentinel has grown substantially over time to comprise 54 member travel/tropical medicine clinics in 24 countries on six continents, with 2,344 records entered from U.S. sites in 2011.

Data collected by GeoSentinel have been used to inform recommendations for travelers and for health-care providers involved in travel medicine. CDC Health Information for International Travel (the Yellow Book) includes numerous published reports from GeoSentinel (30). GeoSentinel also has detected unusual and important health events among travelers and alerted the public health and medical communities worldwide about these occurrences. The recent outbreak of Sarcocystis-like illness in travelers returning from Tioman Island is an example of GeoSentinel sites detecting an outbreak that had not been detected by any other surveillance system. Sarcocystosis is not a reportable disease in any country; this outbreak was detected because of the efficient communication among GeoSentinel sites.

GeoSentinel has the capacity to identify and respond rapidly to aberrations in geographic patterns of illness among travelers, which is particularly important if these travelers originate from multiple nations or regions. GeoSentinel has played a role in identifying outbreaks in the past, including an outbreak of leptospirosis among travelers to Borneo, Malaysia, in 2000 (31). The identification by GeoSentinel of a Romanian traveler who acquired P. vivax malaria in Greece contributed to the investigation of a possible resurgence of malaria transmission there and ultimately informed CDC malaria prophylaxis guidelines for U.S. travelers to the affected region (27,28). The identification by GeoSentinel of incidents of EAT among tourists to Zambia and the adjacent Mana Pools region of Zimbabwe demonstrates that Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense continues to be a threat to the health of travelers to this region. This is especially important because no cases had been reported among travelers during the preceding decade (24). These three important health events demonstrate that GeoSentinel is an effective communications network for clinical and public health information.

Data from U.S. GeoSentinel sites demonstrate that the majority of ill returned travelers in the GeoSentinel database evaluated at U.S. sites are encountered as outpatients and are aged 19–64 years; were traveling for tourism, business, or volunteer purposes; and were returning from Sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, or South America. In comparison with returned travelers evaluated at GeoSentinel sites worldwide during 1999–2011(19,20), travelers evaluated at GeoSentinel sites in the United States during 1997–2011 (as described in this report) were exposed to their illnesses more frequently in Central America or South America and less frequently in South Central Asia or Southeast Asia. This likely reflects different travel patterns among U.S. travelers in comparison with travelers from Europe.

Among patients presenting to U.S. GeoSentinel sites, gastrointestinal diagnoses were recorded most frequently of all syndromic groupings. Acute unspecified diarrhea was among the top two diagnoses for each of the top four regions of exposure (Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, Central America, and Caribbean). These findings suggest that travelers might be exposed regularly to unsafe food or water during international trips. A substantial proportion of these diagnoses, including approximately half of both acute and chronic diarrhea diagnoses, were not attributed to any specific etiology. This reflects the fact that the specialized tests required for diagnosis of some of the most common causes of acute travelers' diarrhea, such as enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), are not used routinely in clinical practice (19). Although there are commonalities in diseases encountered by region of travel, the findings also demonstrate the importance of the use of GeoSentinel data to identify specific differences that vary by region of travel and by specific groups of travelers.

The most frequent diagnosis among the febrile/systemic grouping, as well as the most frequent diagnosis among patients exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa, was P. falciparum malaria. Approximately half of patients who contracted P. falciparum malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa were VFR travelers. Case-based malaria surveillance in the United States also has demonstrated that most P. falciparum cases occur among VFR travelers (32). VFR travelers experience increased burden of travel-related diseases, including malaria (33). Because these data indicate that malaria in U.S. travelers to malaria-endemic areas remains a concern, continuing to promote proper malaria chemoprophylaxis and mosquito bite avoidance to all travelers to malaria-endemic regions of the world should remain a priority. In addition, persons returning from these areas who develop a febrile illness should seek health care immediately, and practitioners should consider malaria as a possible cause for the illness.

CDC recommends that international travelers seek a pretravel medical consultation 4–6 weeks before traveling (34). However, the findings of this report indicate that fewer than half of ill returned travelers evaluated at U.S. GeoSentinel clinics during 1997–2011 reported having had a pretravel encounter with a health-care provider. Many of these travelers visited countries where diseases with limited or no presence in the United States are endemic. Such diseases include malaria, dengue, typhoid, and viral hepatitis. These and other potentially preventable diseases pose health risks to international travelers. Therefore, future efforts should seek to increase the number of travelers who seek pretravel medical consultation in accordance with the CDC recommendation. In addition, health-care providers who see travelers before travel should consider country- and region-specific vaccination, prophylaxis, and disease avoidance recommendations when presented with a traveler's itinerary. Increased use of pretravel consultations, along with improved education for health-care professionals, could result in a decrease in the burden of travel-related disease among U.S. international travelers.

Limitations

The data collected by GeoSentinel are subject to at least four limitations. First, because the findings are limited to travelers who visit participating GeoSentinel Sites, the data are not necessarily representative of all international travelers. As a result, the severity and frequency of illness among returned travelers might be underestimated. Second, because of the lack of denominator data, GeoSentinel data cannot be used to calculate travel-related disease rates or risks. Third, despite the use of standard diagnosis codes, data coding and entry practices might vary by site and over time. Finally, because the GeoSentinel data system has undergone numerous changes (Box 3) and the number of GeoSentinel sites has changed, direct comparisons over time might not be valid.

Conclusion

GeoSentinel is a global, clinic-based surveillance system that collects demographic, travel, and clinical diagnosis surveillance data from ill international travelers during and after travel. The system aims to improve understanding of morbidity in international travelers, inform health recommendations for travelers, and detect important health events among international travelers. Since 1999, GeoSentinel data have been used extensively to characterize travel-related illness (17,19,20) such as malaria (35) and dengue (36). Data from GeoSentinel sites have also been used to link particular travel destinations with rare or geographically unusual diseases among returned travelers (23–25,29). Future efforts to improve GeoSentinel's ability to characterize travel-related illness could include systematic collection of more detailed information from patients.

The findings in this report suggest that travelers from the United States to developing countries remain at risk for travel-related illness. To mitigate this risk, health-care providers should provide evidence-based advice to travelers before travel, as well as destination-specific medical evaluation to ill travelers after travel. Physicians who evaluate travelers before or after travel should be trained on prevention and treatment of a variety of travel-related conditions, with special attention paid to traveler's diarrhea and malaria.

Acknowledgments

The following members of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network contributed data from U.S. sites: DeVon C. Hale, MD, Rahul Anand, MD, Stephanie S. Gelman, MD, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Bradley A. Connor, MD, Cornell University, New York, New York; N. Jean Haulman, MD, David Roesel, MD, Elaine C. Jong, MD, University of Washington and Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Washington; William M. Stauffer, MD, Patricia F. Walker, MD, University of Minnesota and HealthPartners, Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota; Phyllis E. Kozarsky, MD, Henry M. Wu, MD, Jessica Fairley, MD, Carlos Franco-Paredes, MD, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Christina M. Coyle, MD, MS, Murray Wittner, MD, PhD, Albert Einstein School of Medicine, Bronx, New York; Lin H. Chen, MD, Mary E. Wilson, MD, Mount Auburn Hospital, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Carmelo Licitra, MD, Antonio Crespo, MD, Orlando Regional Health Center, Orlando, Florida; Noreen A. Hynes, MD, R. Bradley Sack, MD, ScD, Robin McKenzie, MD, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; John D. Cahill, MD, George McKinley, MD, St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, New York; Stefan Hagmann, MD, Michael Henry, MD, Andy O. Miller, MD, Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, Bronx, New York; Alejandra Gurtman, MD, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York City, New York (October 2002–August 2005); Thomas B. Nutman, MD, Amy D. Klion, MD, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; David O. Freedman, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama; Johnnie A. Yates, MD, Vernon Ansdell, MD, Kaiser Permanente, Honolulu, Hawaii; Michael W. Lynch, MD, Fresno International Travel Medical Center, Fresno, California (August 2003–February 2010); Elizabeth D. Barnett, MD, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts; Susan Anderson, MD, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Palo Alto, California; Susan McLellan, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana (December 1999–August 2005); Paul Holtom, MD, Jeffrey A. Goad, PharmD, Anne Anglim, MD, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California (April 2007–December 2009); Nancy Piper Jenks, MS, and Christine A. Kerr, MD, Hudson River Health Care, Peekskill, New York; Abinash Virk, MD, Irene Sia, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota (October 2009–March 2010).

References

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO tourism highlights: 2012 edition. Madrid, Spain: World Tourism Organization; 2012. Available at http://mkt.unwto.org/en/publication/unwto-tourism-highlights-2012-edition. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- U.S. Department of Commerce. 2009 United States resident travel abroad. Available at http://tinet.ita.doc.gov/outreachpages/download_data_table/2009_US_travel_Abroad.pdf. Accessed date TBD.

- Institute of International Education. Open doors 2011 "fast facts." Available at http://www.iie.org/Research-and-Publications/Open-Doors/Data/Fast-Facts. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- Office of Travel and Tourism Industries. Profile of U.S. resident travelers visiting overseas destinations: 2011 outbound. Available at http://tinet.ita.doc.gov/outreachpages/download_data_table/2011_Outbound_Profile.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- Steffen R, Rickenbach M, Wilhelm U, Helminger A, Schar M. Health problems after travel to developing countries. J Infect Dis 1987;156:84–91.

- Hill DR. Health problems in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. J Travel Med 2000;7:259–66.

- Steffen R, deBernardis C, Baños A. Travel epidemiology—a global perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2003;21:89–95.

- Bacaner N, Stauffer B, Boulware DR, Walter PF, Keystone JS. Travel medicine considerations for North American immigrants visiting friends and relatives. JAMA 2004;291:2856–64.

- Angell SY, Cetron MS. Health disparities among travelers visiting friends and relatives abroad. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:67–72.

- CDC. Update: outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome—worldwide, 2003. MMWR 2003;52:241–8.

- CDC. Update: novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infections—worldwide, May 6, 2009. MMWR 2009;58:453–8.

- CDC. Measles—United States, 2011. MMWR 2012;61:253–7.

- CDC. Update: mumps outbreak—New York and New Jersey, June 2009–January 2010. MMWR 2010;59:125–9.

- CDC. Locally acquired dengue—Key West, Florida, 2009–2010. MMWR 2010;59:577–81.

- Odolini S, Gautret P, Parola P. Epidemiology of imported malaria in the Mediterranean region. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2012;4: e2012031. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3375659. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- CDC. Malaria—Great Exuma, Bahamas, May–June 2006. MMWR 2006;55:1013–6.

- Freedman DO, Kozarsky PE, Weld LH, Cetron MS. GeoSentinel: the global emerging infections sentinel network of the International Society of Travel Medicine. J Travel Med 1999;6:94–8.

- Hill DR, Behrens RH. A survey of travel clinics throughout the world. J Travel Med 1996;3:46–51.

- Leder K, Torresi J, Libman M, et al. GeoSentinel surveillance of illness in returned travelers, 2007–2011. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:456–68.

- Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, et al. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med 2006;354:119–30.

- Moore D, Edwards M, Escombe R, et al. African trypanosomiasis in travelers returning to the United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:74–6.

- ProMED-Mail. Trypanosomiasis—US ex Zambia (eastern). Available at http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20100915.3338. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- Cottle L, Peters J, Hall A, et al. Multiorgan dysfunction caused by travel-associated African Trypanosomiasis. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:287–9.

- Simarro PP, Franco JR, Cecchi G, et al. Human African trypanosomiasis in non-endemic countries (2000–2010). J Travel Med 2012;19:44–53.

- Florescu SA, Popescu CP, Calistru P, et al. Plasmodium vivax malaria in a Romanian traveler returning from Greece, August 2011. Eurosurveillance 2011;16. Available at http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19954. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- ProMED-Mail. Malaria vivax—Germany ex Greece. Available at http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20000713.1158. Accessed date TBD.

- Danis K, Baka A, Lenglet A, et al. Autochthonous Plasmodium vivax malaria in Greece, 2011. Eurosurveillance 2011;16. Available at http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19993. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- ProMED-Mail. Sarcocystosis, human—Malaysia: Tioman Island. Available at http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20111031.3240. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- CDC. Acute muscular sarcocystosis among returning travelers—Tioman Island, Malaysia, 2011. MMWR 2012;61:37–8.

- Brunette GW, Kozarsky P, Magill AJ, Shlim DR, Whatley A, eds. CDC health information for international travel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

- CDC. Update: outbreak of acute febrile illness among athletes participating in eco-challenge-Sabah 2000—Borneo, Malaysia, 2000. MMWR 2001;50:21–4.

- Mali S, Kachur SP, Arguin PM. Malaria surveillance—United States 2010. MMWR 2012;61(No. SS-2)

- Keystone J. Immigrants returning home to visit friends and relatives. In: Brunette GW, Kozarsky P, Magill AJ, Shlim DR, Whatley A, eds. CDC health information for international travel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012:547–51.

- CDC. Travelers' health: see a doctor before you travel. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2013. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/travel/page/see-doctor. Accessed June 25, 2013.

- Leder K, Black J, O'Brien D, et al. Malaria in travelers: a review of the GeoSentinel surveillance network. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:1104–12.

- Schwartz E, Weld LH, Wilder-Smith A, et al. Seasonality, annual trends, and characteristics of dengue among ill returned travelers, 1997–2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1081–8.

* David O. Freedman, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham; Phyllis Kozarsky, MD, Emory University, CDC; Martin Cetron, MD, CDC.

† Additional information about EuroTravNet is available at http://www.istm.org/eurotravnet/main.html.

§ Additional information about TropNet is available at http://www.tropnet.net.

* N = 54.

† N = 235.

Alternate Text: This figure shows a map of the world indicating the locations of 54 GeoSentinel surveillance sites and 235 network members on six continents. The greatest concentration of sites and members is in North America and Western Europe.

FIGURE 2. Geographic region* of exposure for after-travel patients - GeoSentinel Surveillance System, worldwide, 2011

* Region of exposure for current illness was based on modified UNICEF groupings.

Alternate Text: This figure shows a color-coded world map indicating the following GeoSentinel regional groupings: Australia and New Zealand, Caribbean, Central America, Eastern Europe, Middle East, North Africa, North East Asia, Oceania, South America, South Central Asia, South East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Western Europe.

FIGURE 3. Flowchart of patients included in the GeoSentinel database - GeoSentinel Surveillance System, worldwide, 1997-2011

Alternate Text: This figure shows a flowchart of GeoSentinel records included in analysis and described in this report. The total number of patients included in the database was 164,378. The number of patients who received at least one ¬final probable or confi¬rmed travel-related diagnosis was 141,789. The number of patients for whom a final probable or confi¬rmed travel-related diagnosis was lacking was 22,589. The number of patients evaluated in the United States was 23,006, and the number evaluated outside the United States was 118,783. Of the 23,006 patients evaluated in the United States, clinical setting was classified as after travel for 10,032 patients, as immigration only for 12,466 patients, as during travel for 506 patients, and as unspecified for two patients.

FIGURE 4. Number* of patients evaluated in the United States and included in the GeoSentinel database, by year and clinical setting - United States, 1997-2011

* N = 23,004. The 22 GeoSentinel sites did not all necessarily submit data in every year of the reporting period.

Alternate Text: This figure shows the number of GeoSentinel records for 1997-2011, broken down into three clinical settings: seen during travel, seen after travel, and immigration only.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version.

Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.