Core SIPP States in Action

The following success stories highlight how Core SIPP implements, evaluates and disseminates injury prevention strategies into action.

Suicide

Transportation Safety

Health Equity

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Tennessee: Informing Passage of the Safe Stars Act for the 2022-2023 School Year

- New York: Returning to Physical Education Following a Concussion

- Alaska: Aligning Brain Injury Awareness, Prevention, and Screening Efforts Across the State

Shared Risk and Protective Factors (SRPF)

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

What did Montana do?

The city-county health department for Lewis and Clark County created Safer Communities Montana (SCM) with support from the local and state governments and CDC’s Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP). SCM provides free gunlocks and drug deactivation kits to the community for secure storage of firearms and to prevent medication misuse. Secure storage of firearms and safe disposal of medication reduces the risk of suicide. Community partners give free gunlocks to customers and refer them to suicide prevention materials in case someone they know experiences a suicidal crisis. SCM also promotes the free gunlocks, drug deactivation kits, and suicide prevention messaging through TV, radio, and newspaper.

This partnership strategy is innovative because of its personalized approach to the firearm community in these Montana counties, which includes many veterans. SCM relies on community partners’ input and advice for marketing materials and conducting outreach and community engagement. Community partners such as the Prickly Pear Sportsmen’s Association, Capital Sports, and Dave’s Pawn Shop are all active participants in SCM meetings. SCM also collaborated with the local hospital and health clinics in Lewis and Clark County to distribute gunlocks and drug deactivation kits to patients who score high on a depression screener, mention mental health challenges, or want to practice secure storage. SCM serves Broadwater, Jefferson, and Lewis and Clark counties. Lewis and Clark County has about 70,000 residents, half of which live in small rural towns and communities. Broadwater and Jefferson counties have about 18,000 residents combined.

How does Safer Communities Montana impact the counties served?

The goal of SCM is to prevent suicide and reduce access to lethal means for community members at risk for suicide in Lewis and Clark, Broadwater, and Jefferson counties. SCM partnered with 77% of firearm retailers, 75% of gun ranges, and 80% of pawn shops in the three counties. They are working to expand outreach and partnerships to law enforcement, schools, and primary care and emergency department physicians. Feedback from community partners helped SCM create outreach materials appropriate for the firearm community and specifically veterans.

SCM worked with a CDC-supported Injury Control Research Center, Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center, to develop a safe storage map to improve temporary secure storage options for individuals in crisis. Firearm dealers mentioned that liability for self-harm, suicide, or harm against others were obstacles for safe storage arrangements. The Montana State Legislature passed SB423 [PDF – 3 pages] during the 2023 Legislative Session, and it became law when the Governor of Montana signed it in May 2023. This law limits liability for individuals and private companies when they return a firearm to the owner at the end of a firearm hold agreement. The law is intended to increase comfort for Veteran Service Organizations, firearm dealers, and gun ranges to hold firearms temporarily. As a result of this law, SCM will incorporate the new liability limitations for firearm holders into a toolkit to encourage participation in the program.

Why was Safer Communities Montana created?

Montana’s suicide rate ranked among the top two in the nation [PDF – 1 page] and was double the national rate of 14.1 suicides per 100,000 people in 2021. This might be due to several factors such as a lack of mental health services, stigma, and easy access to lethal means. Populations at a higher risk for suicide in Montana [PDF – 12 pages] include veterans, middle-aged white men, and American Indians. Montana’s veteran suicide rate [PDF – 2 pages] was 1.7 times the rate for the general population in 2020.

Firearm ownership is a large part of Montana culture. Montana ranks number one in the nation for household firearm ownership. A factor likely contributing to Montana’s high suicide rate is how easy it is for people in crisis to access lethal means, especially firearms. A person who attempts suicide with a firearm has an 85 – 90% chance of dying. Sixty-eight percent of all suicides in Montana used a firearm in 2021. Sixty-five people died by suicide between 2018–2021 in Lewis and Clark County alone. Of those, 41 used a firearm and 11 died of an intentional overdose. Research indicates that about 9 in 10 people who attempt suicide and survive do not die by suicide later. Preventing access to lethal means at the time of crisis can save lives.

What did Virginia do?

Virginia’s Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) funding provided support for Every Ride, Safe Ride, an outreach project based on existing evidence in safe transportation of children (STC) principles. The initiative’s goal is to equip pediatric and obstetric healthcare providers with the knowledge and resources to assess, screen, provide resources, and address safe transportation through pregnancy to a child’s transition to the seat belt. Virginia Core SIPP partnered with the Virginia Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) to provide:

- Healthcare provider education

- Technical assistance for practice assessment, screening, and referrals to STC resources

- Continuing Medical Education and Maintenance of Certification units for completed professional development and quality improvement projects

Two pediatric practices enrolled by AAP participated in the project. Participants included pediatricians and nurses who used the Plan-Do-Study-Act framework and measured improvement in assessment, screening, and caregiver referrals. Virginia Core SIPP sent a pre-participation survey to enrolled providers to measure current screening practices. Participants received a post-survey to measure their responses to technical assistance.

The Every Ride, Safe Ride Project Dashboard displays three primary project measures: safety screenings conducted, use of appropriate restraints, and safety education, separated by child age range of 0-23 months, 2-7 years, and 8–18 years. Separating the data by age made it easier to find opportunities for improvement across different age ranges with different restraint use needs. Practices collected five cycles of data over six months. They submitted data monthly into the Every Ride, Safe Ride dashboard for continuous program assessment. The measures and benchmarks were:

- Safety screenings

- Benchmark: Complete STC screening at 50% of all child visits each month.

- Appropriate restraints

- Benchmark: 50% of screened seats are the appropriate seat for the age, weight, height, and development of the child.

- Safety education

- Benchmark: Complete STC education at 50% of all child visits each month.

How did Every Ride, Safe Ride impact child passenger safety?

Pre- and post-project surveys showed an improvement in provider comfort addressing child passenger safety (CPS) questions and knowing where to refer caregivers for additional resources. Thirty-six percent of providers indicated a commitment to providing CPS education at every routine doctor’s appointment. The biggest barriers to screening and educating at every visit were time constraints and CPS not being a top priority compared to other topics during the visit.

Participants screened a total of 192 patients for safe transportation practices. Practices that received technical assistance from Virginia Core SIPP improved upon their comprehensive screenings and referrals to STC resources. Participating providers exceeded benchmark goals for safety screenings and appropriate restraints.

Data showed that practices generally screened for STC but missed screening opportunities in each age group before the project. Completion rates reached 100% once the project started, with practices more focused on completing their screenings and receiving frequent dashboard feedback. Participation in the project increased caregiver awareness of STC.

Why did Virginia create Every Ride, Safe Ride?

Historical data showed that healthcare providers in Virginia spend less than two minutes educating families on STC principles. Pediatric healthcare providers can support parents and caregivers in improving safety on the roadways. Virginia’s long-term partnership with AAP allowed for a collaboration to support the state’s healthcare providers to improve how they approach STC during visits.

Virginia Core SIPP’s Child Passenger Safety Program provides proper safety seat installation and use education through a community network of Check Stations for children until they transition to the vehicle safety belt. The program includes education, outreach, and addresses financial barriers that limit access to safety devices through the Low-Income Safety Seat Distribution and Education Program. Motor vehicle travel (MVT) related injuries are among the most preventable causes of injury-related death and hospitalization in Virginia for children ages 0-14 years of age. There were 21 MVT related fatalities for children under 15 years of age in 2021. AAP Bright Futures recommends discussing STC practices at every routine doctor’s appointment for children 0–18 years of age. This project helped support that recommendation and bolstered Virginia Core SIPP’s child passenger safety work.

What did Colorado do?

Colorado’s Weld County Department of Public Health and Environment (WCDPHE) improved their ability to review local land use codes for the 32 communities in Weld County. Local land use codes establish zoning and the processes used for housing development. WCDPHE staff examined land use codes to increase community engagement in housing affordability policy decision making and program design. The goal is to connect built environment policies to the injury and violence prevention field. Improving housing affordability, nutrition security, and transportation safety policies would lead to an increase in economic resilience.

WCDPHE increased their knowledge of housing affordability terms and land use strategies. Colorado Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) staff connected WCDPHE with the Colorado Department of Local Affairs (DOLA) to identify local communities who received DOLA’s 1271 funding. The 1271 grantees are communities who must plan and carry out a strategy to increase affordable housing in Colorado through community planning policies.

Colorado Core SIPP held a networking event that provided WCDPHE and the 1271 grantees working in Weld County the opportunity to create shared goals and use each other’s knowledge, skills, and partnerships to create more housing affordability. About 20 representatives from eight local communities (Garden City, Greeley, Johnstown, Keensburg, Eaton, Evans, Windsor, and Kersey) attended the event on August 4, 2022. A WCDPHE participant said, “this event helped our team make connections with municipal staff and start the conversation around our project and the support we can provide.” WCDPHE connected with the city of Evans after the event and supported a local community engagement event that collected feedback on community development, including housing. WCDPHE created a network with local communities and improved their communication and ability to work across the area on housing affordability efforts.

WCDPHE is a local public health agency funded through the Office of Health Equity (OHE) at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. WCDPHE receives technical assistance through CDC’s Core SIPP to strengthen economic resilience in local communities by informing housing affordability policies. Increasing economic resilience through housing, food, and transportation would reduce risk factors associated with adverse childhood experiences, transportation safety, and traumatic brain injury. WCDPHE’s strategy builds community members’ knowledge and capacity to be involved in housing conversations at the local level.

How did they plan this event?

Core SIPP provided guidance, training, and resources for WCDPHE staff to create more equitable housing conversations in Weld County communities. Additionally, Core SIPP staff hosted a networking and learning event in August 2022 for the WCDPHE and DOLA funded 1271 grantees.

Why did they host this event?

Community development and city design processes include community engagement. WCDPHE found that certain community members are underrepresented in the community development and city design process for Weld County. Residents in the county who participate in city design and community engagement are more likely to be English speakers, educated, and have higher incomes. Many residents who speak languages other than English, have less education, and earn a lower income do not engage in these processes. These residents face greater housing disparities in Weld County. WCDPHE wants to increase representation and equity by including these community members in discussing and identifying policies that would increase housing affordability strategies in communities through their OHE grant. Colorado Core SIPP held the networking event to include representatives from these communities in community development and city design processes. Broadening representation to develop policies, such as housing policies, can create more well-rounded and community supported policies and programs.

What did Tennessee do?

The Tennessee Department of Health launched the free and voluntary Safe Stars initiative in 2018 in partnership with 33 sports and health organizations. This initiative recognizes Tennessee youth sports programs that meet high safety standards for athletes. Safe Stars consists of three levels of recognition: Gold, Silver, and Bronze. Each level requires that the sports program meet certain safety standards determined by a team of health professionals. The Safe Stars initiative success was used to support the Safe Stars Act in 2021.

Tennessee legislators passed the Safe Stars Act establishing certain health and safety requirements for school youth athletic activities in May 2021. The Safe Stars Act officially went into effect for the 2022-2023 school year. This bill applies to any “city, county, business, or nonprofit organization that organizes a community-based youth athletic activity,” each local education agency (LEA), and all public/public charter schools that provide a youth athletic activity. The goal of this Act was to improve safety standards in youth sports by creating policies around concussions and injury prevention.

Each LEA and public/public charter school that provides a school youth athletic activity must develop a code of conduct for coaches under this Act. Schools should visit the department of health’s Safe Stars initiative website to review the safety standards and communicate with the department to ensure that all safety measures are up to date. The Act also requires each LEA and public/public charter school to hold an informational meeting before the start of each school athletic season for students, parents, coaches, and school officials. The purpose of the meeting is to learn about the symptoms and warning signs of sudden cardiac arrest, heat illness, concussions and other head injuries, and other health, safety, and wellness issues related to sports participation.

How did the Safe Stars initiative inform this Act?

The Safe Stars initiative improved knowledge of concussions and other head injuries students might experience during sports which informed the Safe Stars Act. The Safe Stars initiative is a part of the state’s Return to Learn/Play Guideline [PDF – 22 pages]. This guideline helps athletes have a good recovery and get back to regular activities such as school and play, safely, following a concussion or traumatic brain injury.

The Tennessee Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) created the sports league evaluation, application, and promotional materials for the Safe Stars initiative. The Core SIPP Director and Manager developed and maintained a strong relationship with the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association and Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Program for Injury Prevention in Youth Sports to promote the Safe Stars initiative and encourage sports leagues to meet the minimum criteria.

Core SIPP presented at the state Tennessee Athletic Trainers’ Society and two of their regional conferences about the Safe Stars initiative in 2019. Core SIPP shared Safe Stars information with county and city Mayors in October 2019. Mayors often oversee funding for county-wide school districts and recreational centers, which directly prompted an increase in sports leagues applying for Safe Stars.

The Safe Stars initiative is now a part of the Tennessee Department of Health Injury Prevention Program. Core SIPP staff help with the promotion and outreach for the initiative, collection and review of applications, and determination of Safe Stars status for leagues that meet the criteria. The number of sports leagues with a Safe Stars status in Tennessee increased by about 70% since 2018.

Why was this Act created?

About 283,000 children under the age of 18 go to emergency departments each year for a sports- or recreation-related traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the United States. TBIs from contact sports make up approximately 45% of these visits. Over 1,000 Tennessee youth under the age of 25 experienced a TBI in 2022 according to the Tennessee Department of Health. Of those, 222 were under the age of 10. Children may experience changes in their health, thinking, and behavior because of a TBI. Any brain injury in children can disrupt their development and limit their ability to participate in school and other activities, like sports. Tennessee legislators passed this Act to revise and add to the current law regarding injury prevention in school athletics.

What did New York do?

New York adopted new concussion management guidelines for children returning to physical education following a concussion. New York Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) funded the Brain Injury Association of New York State (BIANYS) to develop a Return to Physical Education training program. The training explained the struggles a student may face after having a concussion. The program reached over 2,000 educators in New York State. Core SIPP funding allowed BIANYS to:

- Form a workgroup of people associated with physical education (PE) to develop guidelines for Return to Physical Education.

- Collaborate with the New York State Public High School Athletic Association, which includes coaches and PE teachers, to define differences between Return to Physical Education and Return to Play guidelines. This collaboration included creating a training for PE teachers that explained how Return to Physical Education is different than Return to Play. The training provided examples of how Return to Physical Education can be used at their schools.

- Gather ideas and feedback from discussions with coaches and PE teachers on Return to Physical Education guidelines. This feedback clarified and improved recommendations before submitting proposed Return to Physical Education guideline updates for publication.

How did this impact concussion management guidelines in New York?

BIANYS and their partners proposed an update to New York State Education Department (NYSED) for their Guidelines for Concussion Management in Schools document. NYSED and the New York Department of Health reviewed the proposal and updated the guidelines [PDF – 42 pages] in July 2023. The updated guidelines more clearly discussed the difference between returning to activity in PE versus athletic activities.

Why did New York create new guidelines?

Students are currently not allowed to return to PE class after they sustain a concussion until they are completely symptom free. Most school districts in New York use Return to Play principles for a student to return to PE class. Return to Physical Education should not be the same as Return to Play. Return to Play relates to preparing and clearing student athletes for competition after a concussion. There are no guidelines for returning to PE after a concussion. Studies show that a slow return to physical activity while still symptomatic aids in recovery.

What did Alaska do?

Alaska Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) coordinated traumatic brain injury (TBI)-related communication efforts across state partners. The goal is to improve knowledge about TBI, encourage early detection and treatment of these injuries, and prevent and reduce these types of injuries across the state. Alaska Core SIPP created a communications plan to ensure partners share data, evidence-based information, and resources with focus populations. The focus populations for this project were youth in schools, youth in the juvenile justice system, parents, and teachers.

How did Alaska improve knowledge of traumatic brain injuries?

Alaska Core SIPP created the “Defend Your Brain” public education campaign across the state. This campaign included creating a TBI website along with 36 social media messages. The campaign focused on early detection, treatment, and prevention of TBI. The website and social media messages helped people find resources and support after a brain injury. Alaska Core SIPP shared these materials across various channels including the Alaska Department of Health Facebook and Instagram pages, websites, TV, YouTube, and Snapchat between April and June 2022. This strategy resulted in over 2,650,000 displays of online messages and over 4,700 visits to the Defend Your Brain campaign website. The social media campaign alone reached 225,181 Alaskans.

Alaska Core SIPP hired a Youth Brain Injury Coordinator in September 2022 hosted by Alaska’s educational resource agency, the Southeast Regional Resource Center. This position focuses on supporting the Division of Juvenile Justice and building school supports for children who experience TBI. The Youth Brain Injury Coordinator also:

- Assists with the formation of brain injury teams in the schools.

- Holds presentations and educates students and families about TBI.

- Helps with school education plans, accommodations, and behavior strategies.

- Eases communication between school, medical, and juvenile corrections staff.

- Creates flyers about the Youth Brain Injury Program and what it offers, such as training for teachers on brain injury and best practices in the classroom.

- Spreads awareness of new brain injury resources in Alaska for educators, parents, and school support staff.

Why did Alaska create this campaign?

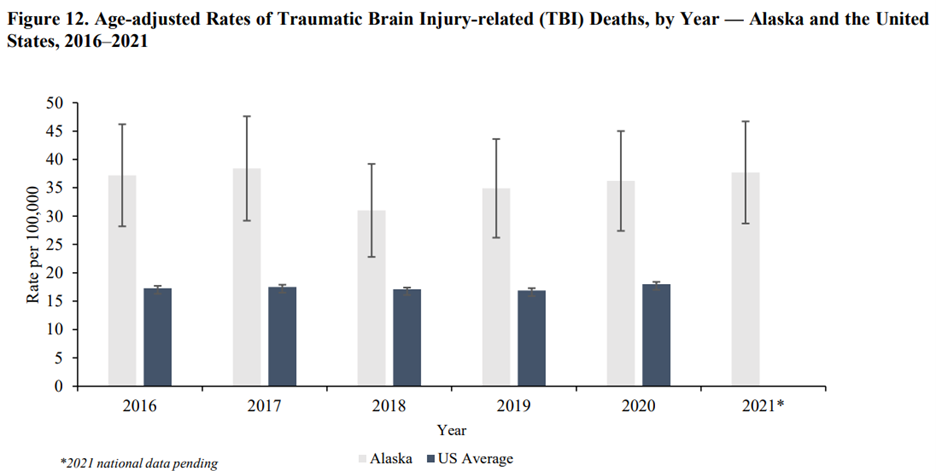

Alaska has one of the highest rates of TBI [PDF – 37 pages] in the nation. Alaska TBI-related mortality was the highest in the nation and more than twice the national average between 2016 and 2021.

The Alaska Department of Health (AK-DOH) developed brain injury awareness, prevention, and screening efforts to focus on disproportionately affected populations. About 40% of youth involved in the juvenile justice system have a history of brain injury. The AK-DOH Core SIPP staff coordinated a brain injury awareness public education campaign, developed a standard process for brain injury screening in the juvenile justice system, and connected youth who experienced TBIs to community and school-based supports.

California

What did California do?

The California Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) team created a webinar called “Shared Risk and Protective Factors: The Future of Injury and Violence Prevention Work!” The webinar occurred in the summer of 2022, and highlighted work from Oregon and Safe States Alliance subject matter experts. The goal of the webinar was for California Department of Public Health’s (CDPH) Injury and Violence Prevention Branch (IVPB) staff to:

- Gain a basic understanding of the shared risk and protective factor (SRPF) approach for injury prevention

- Understand the value of using a SRPF approach with their resources and programs and support the health department’s focus on incorporating health equity, using an anti-racist lens, and aligning with California’s public health priorities

- Learn how other states use a SRPF approach to improve outcomes in injury and violence prevention

This activity connected California injury prevention staff with resources from the Safe States Alliance and other state partners. The webinar helped lay a foundation for California staff to advance injury and violence prevention work through a SRPF approach. California Core SIPP continues to use the SRPF webinar recording to help direct new staff.

What was the impact of the webinar?

California’s Core SIPP team administered a six-question follow-up survey to injury prevention staff to guide future SRPF efforts. The data from the survey will help a new workgroup continue the team’s SRPF growth, learning, and implementation in their programs. The webinar:

- Encouraged collaboration and strengthened relationships the Oregon state public health department and other SRPF subject matter experts

- Created a basic SRPF understanding for their branch

- Solidified plans to create a branch wide SRPF workgroup (which kicked off in May 2023) to incorporate this new knowledge into injury and violence prevention work. Future meetings are planned for the coming year.

Why did they create the webinar?

CDPH wanted to incorporate a SRPF approach into all injury and violence prevention work. Including a SRPF approach aligns with CDPH’s priorities to advance population health equity through social determinants of health, anti-racism, and trauma-informed decisions. CDPH found that IVPB staff had different levels of familiarity with SRPFs. This led the Core SIPP team and CDPH leadership to create a webinar that introduced all IVPB staff to the SRPF approach. The intended audience was IVPB staff who are responsible for a variety of violence prevention and unintentional injury prevention programs and surveillance activities.

New Mexico

What did New Mexico do?

New Mexico Core State Injury Prevention Program (SIPP) developed an introductory training for the New Mexico Injury Prevention Coalition (NMIPC) and partners on shared risk and protective factors (SRPFs), injury prevention, and the social ecological model (SEM). The University of New Mexico Prevention Research Center, NMIPC, and the New Mexico Department of Health staff helped develop the training, which took place on National Injury Prevention Day in November 2022. The training raised awareness and improved knowledge of how the SRPF approach can apply to injury prevention. Objectives of the training included describing risk factors and general causes of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), and motor vehicle crashes (MVCs). New Mexico Core SIPP created a pre- and post-test to evaluate how well participants understood SRPFs and the SEM before and after the presentation. New Mexico Core SIPP developed the training based on analysis of the pre-test and evaluated the training based on the post-test. The training also provided an opportunity to discuss injury prevention in New Mexico using a SRPF approach.

What was the impact of the training?

Mexico Core SIPP sent out a pre- and post-test survey to the 50 registered participants. A total of 37 participants responded to the pre-test, and 28 responded to the post-test. Only 21% of participants strongly agreed that they understood shared risk factors and 13% strongly agreed that they understood shared protective factors for injury prevention before the presentation. All participants reported a better understanding of the concept of shared risk and protective factors following the presentation. Each survey participant found the presentation useful to their work. Participants had diverse ideas of the shared risk and protective factors that they found most important to address. Participants prioritized improving access to safe childcare, mental health services, and economic opportunities and reducing access to alcohol at community events.

Why did they create the training?

The SRPF approach helps injury prevention professionals to build on the protective factors already in place while focusing on reducing specific risk factors for New Mexico communities. New Mexico faces many challenges to improve injury outcomes. These challenges include high rates of poverty, including children living in poverty, lack of economic opportunity, and high rates of ACEs. New Mexico Core SIPP decided to move injury prevention efforts away from individual level outcome-based approaches towards SRPF approaches. SRPF approaches have the potential to impact multiple outcomes. New Mexico also has a centralized Public Health System that relies heavily on partners to carry out health programs. These partners generally focused on individual level outcomes, and New Mexico Core SIPP recognized a need for injury-related SRPF and SEM education for all staff and partners. The CDC Core SIPP funding provided a concrete way to provide training on these approaches to staff and state partners.

What did Mississippi do?

Mississippi Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) created an adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) Task Force informed by a training they developed for early childhood education teachers titled, “Unpacking the Impact: Understanding Adverse Childhood Experiences and their Effects on Child Development.” The Task Force used National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data from 2019 which suggested that the percentage of children in Mississippi who have more than two ACEs is nearly 24% which is higher than the nation’s average of almost 19%. Mississippi Core SIPP collaborated with a local licensed psychologist to design the training. The goal of the training is to help strengthen communities’ ability to understand the potential harms of ACEs and how communities can play a role in preventing ACEs. The training will soon be available on the state’s Department of Health website so that others interested in the training can access it.

How will the ACEs Task Force impact Mississippi?

The ACEs Task Force will share resources and assist community partners, initially in 10 communities, to take a shared risk and protective factors approach to ACEs prevention. It will also inform communities where to access additional ACEs resources within their designated trauma area. The ACEs Task Force works with communities to develop collaborative strategies to support public health actions for ACEs prevention alongside a variety of partners and agencies.

Why did Mississippi create the ACEs Task Force?

The NSCH stated that 26% of children ages 0-17 in Mississippi experienced one ACE as of 2019, while the national average of children who experienced one ACE is 21.1%. ACEs are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood or aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding. ACEs can have lasting, negative effects on health and wellbeing in childhood and life opportunities, such as education and job potential, well into adulthood. These experiences can increase the risks of injury, sexually transmitted infections, maternal and child health problems, and chronic diseases. ACEs vary by individual and population-level characteristics. The NSCH 2019 data showed that non-Hispanic Black youth in Mississippi are disproportionately impacted by ACEs. Building connections across partners can improve knowledge surrounding best practices for ACEs prevention. This includes increasing protective factors and reducing risk factors while focusing on health equity in ACEs prevention.

Additional ACEs prevention tools and trainings can be found here.

What will Minnesota do?

Minnesota Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) is creating a publicly available dashboard visualizing data on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) protective and risk factors. They considered 78 protective factors that could help prevent ACEs. Based on a series of meetings with over 100 school behavioral health professionals, the 78 factors were prioritized and refined to a list of 15 factors that they could track over time.

How will they create the dashboard?

Minnesota Core SIPP will analyze the quality of potential Minnesota ACEs data sources and gather the data they collected from school professionals. The dashboard will include key data indicators from several sources, including:

- Argonne National Laboratory

- The American Community Survey

- The Minnesota Student Survey

- Minnesota Department of Human Services

- Minnesota Department of Public Safety

- Minnesota County Health Rankings

- Minnesota Department of Education

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Environment Atlas

- U.S. Census Bureau

Why are they creating the dashboard?

Schools expressed a need to better understand ACEs that children in Minnesota experience, and a need to better understand protective factors. Minnesota does not have a readily available resource for school district staff about the number of people in Minnesota who experience ACEs or who have ACEs-related risk and protective factors organized by age, race, ethnicity, and school district. This dashboard will serve as a centralized location for pertinent ACEs information to help inform action and prevention efforts.

What did North Carolina do?

North Carolina Core State Injury Prevention Program (Core SIPP) developed a new program named Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Suicide Prevention in a Remote Environment (ASPIRE). The ASPIRE program included: 1) a six-month Collaborative Learning Institute (CLI) training program on using systems thinking approaches for ACEs and suicide prevention planning and 2) two toolkits designed to improve learning and demonstrate best practices for ACEs and suicide prevention.

Partners who conducted the program were the North Carolina Injury and Violence Prevention Branch, University of North Carolina (UNC) Injury Prevention Research Center, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, and the Rural Opportunities Institute. North Carolina Core SIPP collects and analyzes data after each CLI round to improve the structure and delivery of the program and tools in the next round. There have been a total of five CLI cohorts since 2020.

How did North Carolina use systems thinking approaches to improve suicide and ACEs prevention?

The CLI program combined systems thinking approaches with an understanding of ACEs- and suicide-related risk and protective factors to inform prevention. The program included virtual learning with supportive resource materials, recorded sessions for review and additional learning, skill-building exercises, and ongoing feedback and support from coaches.

One of the first tasks for suicide prevention was to add to the outcomes and various types of shared risks and protective factors found in CDC’s Connecting the Dots: An Overview of the Links Among Multiple Forms of Violence [PDF – 16 pages]. North Carolina Core SIPP recruited specifically for teams working in suicide prevention, in addition to teams working in ACEs prevention, in the first round of the CLI. The year one webinar co-hosted by the Safe States Alliance highlighted CLI outcomes from that team. This webinar description is archived on the Safe States website.

Evaluation data collected through focus groups with CLI teams, post-webinar surveys, and pre- and post-test surveys before and after each CLI session and for the overall program, revealed several program strengths. Participants stated an appreciation for the dedicated time to work together as a team on ACEs strategic planning alongside a coach. One participant wrote, “I really like that each group has a CLI rep to help guide us when we have questions or are confused.” Several participants noted a change in perspective that helped their team approach ACEs in a new way. One participant noted, “This institute gave us the lens that we needed to reframe our work in a meaningful and clear way.” North Carolina Core SIPP plans to complete follow-up surveys and/or interviews with previous CLI participants to learn more about outcomes they experienced after participating in CLI. Questions for the participants will include: Are they still functioning as a team? Has their collaboration strengthened because of CLI? Have they implemented a new strategy or developed a new policy based on participation? Do they have new partners? Were there changes within organizations that participated? Has the overall ACEs prevention system changed in their community?

Why did North Carolina create the ASPIRE program?

ACEs and suicide have related risk factors. Communities in North Carolina aim to prevent both suicide and ACEs by creating programs and strategies. However, most of these efforts do not use a systems thinking approach when creating their programs and strategies. Systems thinking could improve their communication about how their programs interact to prevent counter-productive outcomes or duplicated efforts. A systems thinking approach ensures programs and strategies meet the needs of children and families and are created with collaboration, aligned with other community efforts, and have enough resources to support them. There are more than 40 ACEs task forces across the state that can integrate systems thinking into their programs and strategies. Organizations that are a part of these task forces include local public health and social services, child advocacy centers, and other family support services agencies. Increasing the use of systems thinking in planning and establishing ACEs programs requires an improvement in skills, resources, and knowledge through training and technical assistance.