Where Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Comes From

Where does Coccidioides live?

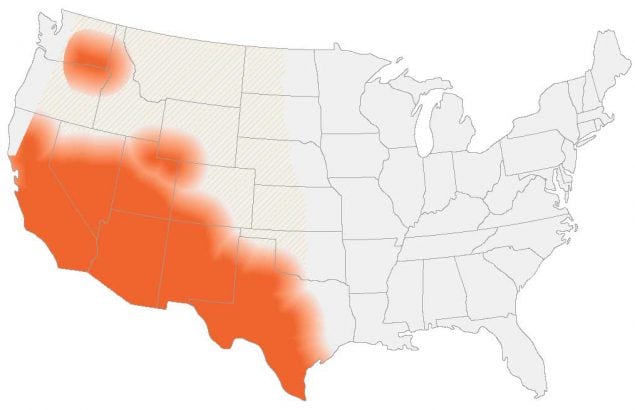

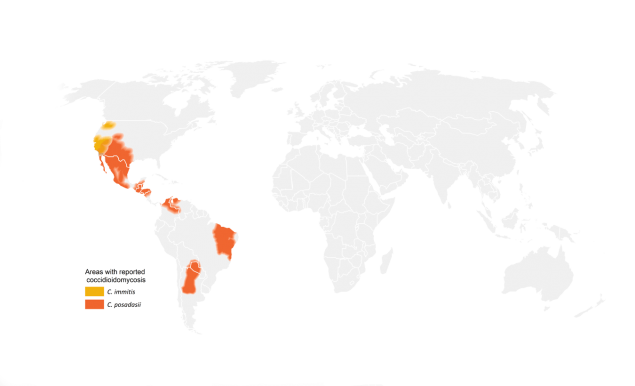

Coccidioides lives in dust and soil in some areas in the southwestern United States, Mexico, and South America. In the United States, Coccidioides lives in Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. The fungus was also recently found in south-central Washington.1,2,3,4

These maps show CDC’s current estimate of where the fungi that cause coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) live in the environment. These fungi are not distributed evenly in the shaded areas, might not be present everywhere in the shaded areas, and can also be outside the shaded areas. Darker shading shows areas where Coccidioides is more likely to live. Diagonal shading shows the potential range of Coccidioides.

More Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) maps.

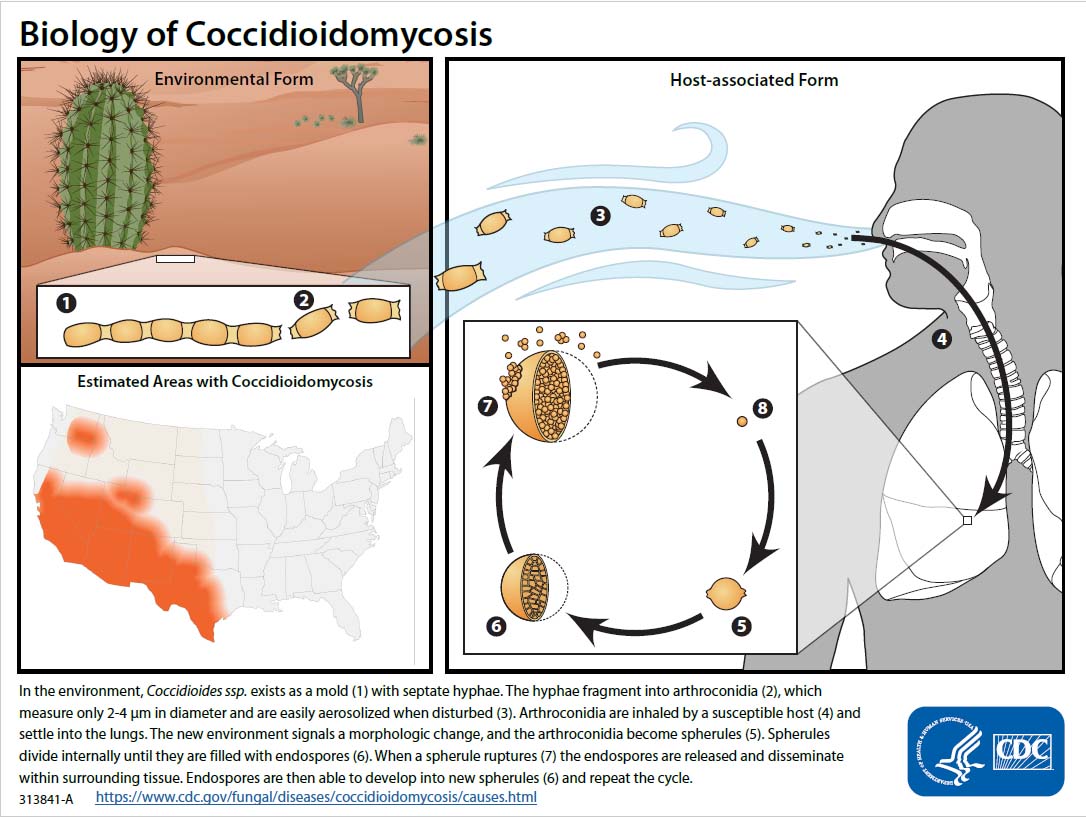

Life Cycle of Coccidioides

Coccidioides spores circulate in the air after contaminated soil and dust are disturbed by humans, animals, or the weather. The spores are too small to see without a microscope. When people breathe in the spores, they are at risk for developing Valley fever. After the spores enter the lungs, the person’s body temperature allows the spores to change shape and grow into spherules. When the spherules get large enough, they break open and releases smaller pieces (called endospores) which can then potentially spread within the lungs or to other organs and grow into new spherules.

PDF version of image pdf icon[823 KB] for printing.

Uncommon sources of Valley fever

The most common way for someone to get Valley fever is by inhaling Coccidioides spores that are in the air. In extremely rare cases, people can get the infection from other sources, such as:

Testing Soil

Testing soil for Coccidioides is sometimes done as a research activity.

I’m worried that Coccidioides is in the soil near my home. Can someone test the soil to find out if the fungus is there?

No, in this situation, testing soil for Coccidioides isn’t likely to be useful because the fungus is thought to be common in the soil in certain areas. A soil sample that tests positive for Coccidioides doesn’t necessarily mean that the soil will release the fungus into the air and cause infection. Also, there are no commercially-available tests to detect Coccidioides in soil. Testing soil for Coccidioides is currently only done for scientific research.

Testing soil for research

Scientists sometimes test soil or other environmental samples for Coccidioides to understand more about its habitat and how weather or climate patterns may affect its growth. The available methods to detect Coccidioides in the soil don’t always detect Coccidioides spores even if they are present. However, new tests are being developed so that researchers can better detect Coccidioides in the environment.

Click here to learn more about how CDC is using advanced molecular detection (AMD) methods to better understand the geographic distribution of Coccidioides.

Valley Fever and the weather

Scientists continue to study how weather and climate patterns affect the habitat of the fungus that causes Valley fever. Coccidioides is thought to grow best in soil after heavy rainfall and then disperse into the air most effectively during hot, dry conditions. 9 For example, hot and dry weather conditions have been shown to correlate with an increase in the number of Valley fever cases in Arizona 10 and in California (but to a lesser extent). 11 The ways in which climate change may be affecting the number of Valley fever infections, as well as the geographic range of Coccidioides, isn’t known yet, but is a subject for further research.

Geographic range of Valley fever expands to Washington State

Scientists believed that Coccidioides only lived in the Southwestern United States and parts of Latin America until discovering it in south-central Washington in 2013 after several residents developed Valley fever without recent travel to areas where the fungus is known to live. Samples from one patient and soil from the suspected exposure site were analyzed using a laboratory technique called whole genome sequencing and were found to be identical, proving that the infection was acquired in Washington.

After this discovery, many unanswered questions remain: How widespread is Coccidioides in Washington? How did it get there? How long has it been living there? Information about where a person was most likely infected with Valley fever, how strains are related, and which areas could pose a risk is essential for raising awareness about the disease among public health officials, healthcare providers, and the public. CDC is working with state and local public health officials and other agencies to better understand where the fungus lives so that healthcare providers and the public can be aware of the risk for Valley fever.

- Marsden-Haug N, Goldoft M, Ralston C, Limaye AP, Chua J, Hill H, et al. Coccidioidomycosis acquired in Washington stateexternal icon. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Mar;56(6):847-50.

- Lockhart, Shawn R et al. “Endemic and Other Dimorphic Mycoses in The Americas.”external icon Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 7,2 151. 20 Feb. 2021

- Hanna, Oltean N et al. “Utility of Whole-Genome Sequencing to Ascertain Locally Acquired Cases of Coccidioidomycosis, Washington, USA.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 25, 3, 501-506. March 2019

- Hanna, Oltean N et al. “Suspected Locally Acquired Coccidioidomycosis in Human, Spokane, Washington, USA.” Emerging Infectious Diseases vol. 26, 3, 606-609. March 2020

- Dierberg KL, Marr KA, Subramanian A, Nace H, Desai N, Locke JE, et al. Donor-derived organ transplant transmission of coccidioidomycosisexternal icon. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012 Jun;14(3):300-4.

- Eckmann BH, Schaefer GL, Huppert M. Bedside interhuman transmission of coccidioidomycosis via growth on fomites. An epidemic involving six personsexternal icon. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1964 Feb;89:175-85.

- Dweik M, Baethge BA, Duarte AG. Coccidioidomycosis pneumonia in a nonendemic area associated with infliximabexternal icon. South Med J. 2007 May;100(5):517-8.

- Stagliano D, Epstein J, Hickey P. Fomite-transmitted coccidioidomycosis in an immunocompromised childexternal icon. Ped Infect Dis J. 2007 May;26(5):454-6.

- Smith CE, Beard RR, Rosenberger HG, Whiting EG, et al. Effect of season and dust control on coccidioidomycosis. J Am Med Assoc. 1946 Dec 7;132(14):833-8.

- Park BJ, Sigel K, Vaz V, Komatsu K, McRill C, Phelan M, et al. An epidemic of coccidioidomycosis in Arizona associated with climatic changes, 1998-2001external icon. J Infect Dis. 2005 Jun 1;191(11):1981-7.

- Zender CS, Talamantes J. Climate controls on valley fever incidence in Kern County, Californiaexternal icon. Int J Biometerol. 2006 Jan;50(3):174-82

- Edwards PQ, Palmer CE. Prevalence of sensitivity to coccidioidin, with special reference to specific and nonspecific reactions to coccidioidin and to histoplasminexternal icon. Dis Chest.1957 Jan;31(1):35-60.

- Werner SB, Pappagianis D. Coccidioidomycosis in Northern California. An outbreak among archeology students near Red Bluffexternal icon. Calif Med. 1973 Sep;119(3):16-20.

- Werner SB, Pappagianis D, Heindl I, Mickel A. An epidemic of coccidioidomycosis among archeology students in northern Californiaexternal icon. N Engl J Med. 1972 Mar 9;286(10):507-12.

- Petersen LR, Marshall SL, Barton-Dickson C, Hajjeh RA, Lindsley MD, Warnock DW, et al. Coccidioidomycosis among workers at an archeological site, northeastern Utahexternal icon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004 Apr;10(4):637-42.

- Hector RF, Laniado-Laborin R. Coccidioidomycosis–a fungal disease of the Americasexternal icon. PLoS Med. 2005 Jan;2(1):e2.