Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP): Clinical Testing Algorithm for Blastomycosis

This clinical testing algorithm was made in collaboration with the Mycoses Study Group Education & Research Consortium.

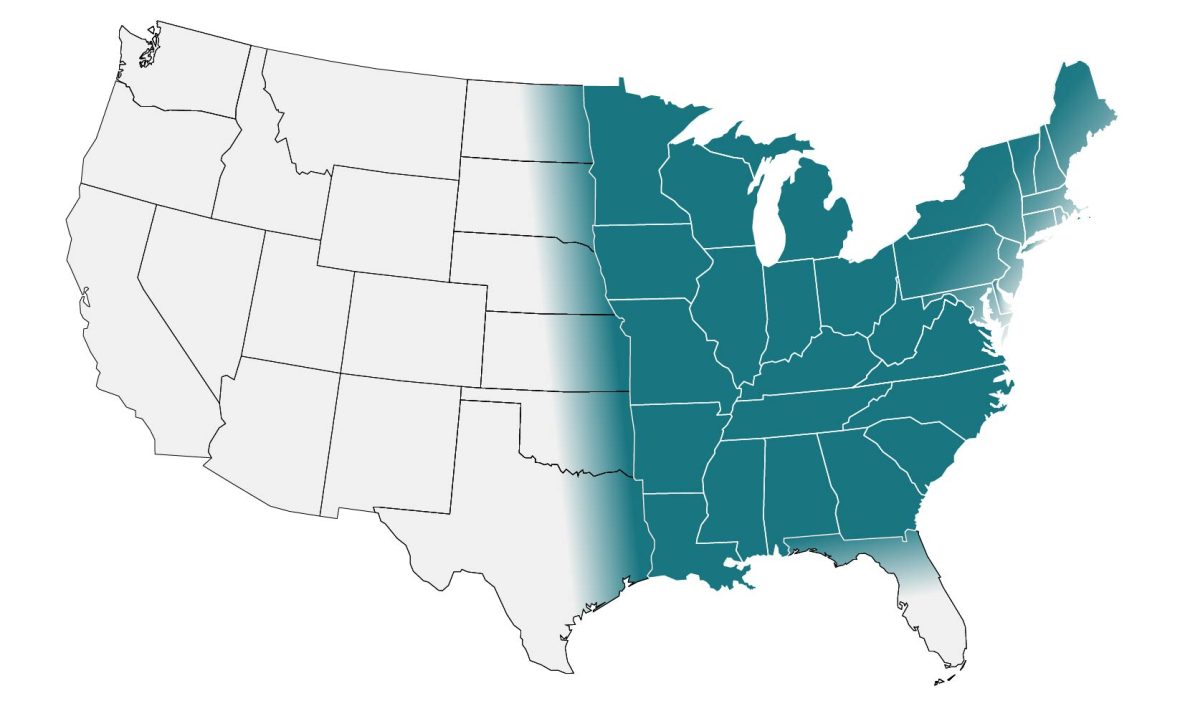

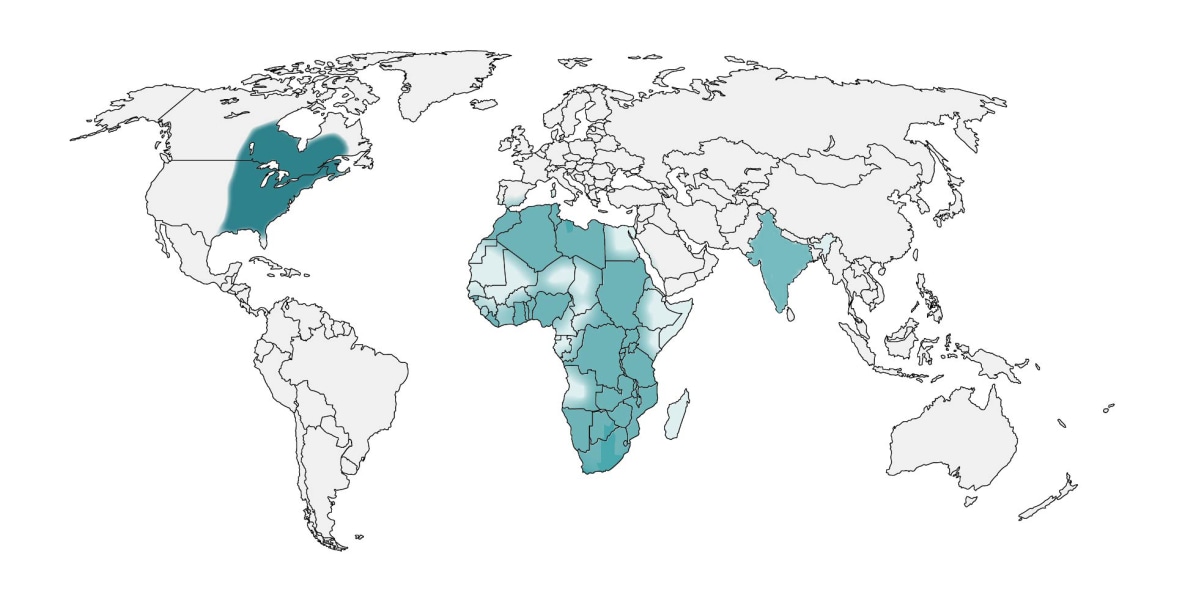

In the United States, blastomycosis is endemic to the Midwest, South and Northeast. Globally, it is endemic in parts of Africa and India. These maps are approximations. Blastomyces is not distributed evenly and may not be present everywhere within the shaded areas. It may also be present outside of the areas indicated.

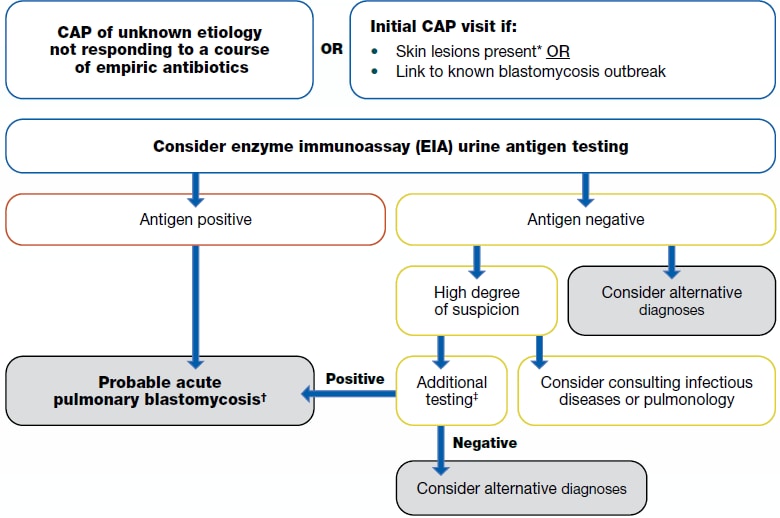

If a patient lives in or has traveled to a disease-endemic area and has:

1a. CAP of unknown etiology not responding to a course of empiric antibiotics

or

1b. Initial CAP visit if:

- Skin lesions present* or

- *Skin lesions could be indicative of late disease or traumatic inoculation rather than acute pulmonary blastomycosis.

- Link to known blastomycosis outbreak

2. Consider enzyme immunoassay (EIA) urine antigen testing

- Antigen positive

- Probable acute pulmonary blastomycosis

- Blastomyces antigen tests have extensive cross-reactivity with Histoplasma. However, both infections are typically treated in a similar manner for most clinical manifestations

- Probable acute pulmonary blastomycosis

- Antigen negative

- Consider alternative diagnosis

- If there is a high degree of suspicion:

- Consider consulting infectious disease or pulmonary

- Additional testing:

- Sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture and microscopy; skin biopsy (if lesion exists) for histopathology; or serologic antibody tests. Evaluation of other non-pulmonary manifestations in the bone, genitourinary tract, and central nervous system may be helpful in diagnosis.

- If the additional testing is positive, then probable acute pulmonary blastomycosis.

- Blastomyces antigen tests have extensive cross-reactivity with Histoplasma. However, both infections are typically treated in a similar manner for most clinical manifestations

- If additional testing is negative, then consider alternate diagnosis

Information About blastomycosis

About Blastomycosis

See Clinical Infectious Diseases publication, Clinician Outreach and Communications Activity Call, and Medscape Article covering the blastomycosis algorithm.

- Clinical Testing Guidance for Coccidioidomycosis, Histoplasmosis, and Blastomycosis in Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia for Primary and Urgent Care Providers | Clinical Infectious Diseases | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

- Webinar Thursday, September 21, 2023 – Algorithms for Diagnosing the Endemic Mycoses Blastomycosis, Coccidioidomycosis, and Histoplasmosis (cdc.gov)

- Three Cases of Community-Acquired Pneumonia (medscape.com)

Blastomycosis is an invasive fungal disease that often presents as community-acquired pneumonia in primary and urgent care settings; however, it is less common than coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis except in certain hyperendemic areas, such as northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. Blastomycosis cannot be reliably distinguished from other causes of respiratory illness by signs or symptoms alone. Thus, patients are commonly misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated with antibiotics—up to 2.5 courses of antibacterial medications are given on average before proper diagnosis.1 Patients hospitalized with blastomycosis have been identified across the United States, and cases have been reported in areas thought to be outside of known endemic areas.2–4

When to Consider Testing for Blastomycosis

Clinicians may consider testing for blastomycosis in patients with community-acquired pneumonia who have failed at least one course of empiric antibiotics and who live in or have traveled to an area where blastomycosis is thought to be endemic (midwestern, south central, and southeastern states, particularly around the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, the Great Lakes, and the Saint Lawrence River. Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota may be hyperendemic for Blastomyces).2,5,6

Clinicians may also consider testing for blastomycosis on an initial presentation of community-acquired pneumonia with one of the following:

How to Test for Blastomycosis

We recommend ordering an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) urine antigen test initially for blastomycosis diagnosis. EIA urine antigen tests may have the highest sensitivity of noninvasive tests and the quickest turnaround time. If the EIA urine antigen is negative, clinicians should consider alternative diagnoses. Alternatively, if a high degree of suspicion remains, additional diagnostic options include sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) culture and microscopy as well as skin biopsies (if lesion exists) for microscopy. Evaluation of other non-pulmonary manifestations in the bone, genitourinary tract, and central nervous system may be helpful in diagnosis. Available serologic antibody tests are reported to have low sensitivity, though they may be a useful adjunct diagnostic test when an antigen test is negative or when trying to differentiate blastomycosis from histoplasmosis (e.g., if done in combination with Histoplasma antibody testing). Consultation with specialists in infectious diseases or pulmonology may be considered if a high degree of suspicion remains as well.

Blastomyces antigen tests have extensive cross-reactivity with Histoplasma. Both infections are treated the same way in most clinical manifestations.

Clinicians should refer to the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s blastomycosis treatment guidelines or an infectious disease physician when determining therapy after a positive result.7

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | Populations studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody tests | |||

| Complement fixation (CF) antibody13,15,16 | 9%–57% | 30%–100% | Adult populations, outbreak settings |

| Immunodiffusion (ID) antibody8,13–17 | 28%–65% | 100% | Adult populations, outbreak settings |

| Antigen Tests | |||

| EIA urine antigen8–12 | 76%–93% | High (but does cross-react with Histoplasma) | Adult populations |

| EIA serum antigen8–12 | 56%–82% | High (but does cross-react with Histoplasma) | Adult populations |

| Other Tests | |||

| Histopathology18 | 81% | 100% | Adult populations |

| Cytology8,18 | 38%–97% | 100% | Adult populations, pregnancy |

- Alpern JD, Bahr NC, Vazquez-Benitez G, Boulware DR, Sellman JS, Sarosi GA. Diagnostic Delay and Antibiotic Overuse in Acute Pulmonary Blastomycosis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(2):ofw078. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw078

- Seitz AE, Younes N, Steiner CA, Prevots DR. Incidence and Trends of Blastomycosis-Associated Hospitalizations in the United States. Chaturvedi V, ed. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105466. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105466

- McDonald R, Dufort E, Jackson BR, et al. Notes from the Field: Blastomycosis Cases Occurring Outside of Regions with Known Endemicity — New York, 2007–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(38):1077-1078. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6738a8

- Schwartz IS, Wiederhold NP, Hanson KE, Patterson TF, Sigler L. Blastomyces helicus, a New Dimorphic Fungus Causing Fatal Pulmonary and Systemic Disease in Humans and Animals in Western Canada and the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(2):188-195. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy483

- McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS. Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Blastomycosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):435-449. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2017.04.006

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and Laboratory Update on Blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(2):367-381. doi:10.1128/CMR.00056-09

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Blastomycosis: 2008 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(12):1801-1812. doi:10.1086/588300

- Carlos WG, Rose AS, Wheat LJ, et al. Blastomycosis in Indiana. Chest. 2010;138(6):1377-1382. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0627

- Durkin M, Witt J, LeMonte A, Wheat B, Connolly P. Antigen Assay with the Potential to Aid in Diagnosis of Blastomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(10):4873-4875. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.10.4873-4875.2004

- Bariola JR, Hage CA, Durkin M, et al. Detection of Blastomyces dermatitidis Antigen in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Blastomycosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69(2):187-191. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.09.015

- Connolly P, Hage CA, Bariola JR, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis Antigen Detection by Quantitative Enzyme Immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19(1):53-56. doi:10.1128/CVI.05248-11

- Frost HM, Novicki TJ. Blastomyces Antigen Detection for Diagnosis and Management of Blastomycosis. Diekema DJ, ed. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(11):3660-3662. doi:10.1128/JCM.02352-15

- Turner S, Kaufman L, Jalbert M. Diagnostic Assessment of an Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay for Human and Canine Blastomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23(2):294-297. doi:10.1128/jcm.23.2.294-297.1986

- Vasquez JE, Mehta JB, Agrawal R, Sarubbi FA. Blastomycosis in Northeast Tennessee. Chest. 1998;114(2):436-443. doi:10.1378/chest.114.2.436

- Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological Tests for Blastomycosis: Assessments During a Large Point-Source Outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155(2):262-268. doi:10.1093/infdis/155.2.262

- O’Dowd TR, Mc Hugh JW, Theel ES, et al. Diagnostic Methods and Risk Factors for Severe Disease and Mortality in Blastomycosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Fungi. 2021;7(11):888. doi:10.3390/jof7110888

- Martynowicz MA, Prakash UBS. Pulmonary Blastomycosis. Chest. 2002;121(3):768-773. doi:10.1378/chest.121.3.768

- Wheat LJ, Knox KS, Hage CA. Approach to the Diagnosis of Histoplasmosis, Blastomycosis and Coccidioidomycosis. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2014;6(3):337-351. doi:10.1007/s40506-014-0020-6