Impaired Driving: Get the Facts

- In 2020, 11,654 people were killed in motor vehicle crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers, accounting for 30% of all traffic-related deaths in the United States.1 This was a 14.3% increase compared to the number of crash deaths involving alcohol-impaired drivers in 2019.1

- 32 people in the United States are killed every day in crashes involving an alcohol-impaired driver—this is one death every 45 minutes.1

- The annual estimated cost of crash deaths involving alcohol-impaired drivers totaled about $123.3 billion* in 2020.2 These costs include medical costs and cost estimates for lives lost.

- Drug-impaired driving is also an important public health problem3; however, less is known about the harmful effects of drug-impaired driving compared to alcohol-impaired driving because of data limitations.4

- 62% of people who died in crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers in 2020 were the alcohol-impaired drivers themselves; 38% were passengers of the alcohol-impaired drivers, drivers or passengers of another vehicle, or nonoccupants (such as a pedestrian).1

- 229 children ages 0–14 years were killed in crashes involving an alcohol-impaired driver in 2020. This was 21% of traffic-related deaths among children ages 0–14 years.1

- It is not known how many people are killed each year in crashes involving drug-impaired drivers because of data limitations.4 However, some studies have assessed drivers for alcohol and drugs in their systems. For example, a study at 7 trauma centers of 4,243 drivers who were seriously injured in crashes found that 54% of drivers tested positive for alcohol and/or drugs from September 2019 to July 2021. Of these, 22% of the drivers were positive for alcohol, 25% were positive for marijuana, 9% were positive for opioids, 10% were positive for stimulants, and 8% were positive for sedatives.5

Safe driving requires focus, coordination, good judgment, and quick reactions to the environment. Any alcohol or other drug use impairs the ability to drive safely.

The amount of alcohol in a person’s system can be measured. This measurement is called blood alcohol concentration (BAC). Most states have set the legal BAC limit for driving at 0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter (g/dL); the limit is 0.05 g/dL in Utah.6 However, impairment starts at lower BAC levels. Information on the effects of alcohol on driving at a range of BACs is available here.

We know a lot about alcohol’s effects on driving, but more research is needed to fully understand the impact of drugs on driving skills.7 However, research has shown that both legal and illicit drugs impair the skills needed to drive safely. For example:

- Some of the effects of being impaired by marijuana that can affect driving include slowed reaction time and decision making, impaired coordination, and distorted perception.7–10

- Other drugs (such as cocaine or illicit amphetamines) can also impair skills like perception, memory, and attention in the short or long term.7

- Prescription and over-the-counter medications can cause many side effects that can impact driving, such as sleepiness, impaired vision, and impaired coordination.11

- Use of multiple substances (such as marijuana and alcohol) at the same time can increase impairment.10,12

About 1 million arrests are made in the United States each year for driving under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs.13,14 However, results from national self-report surveys show that these arrests represent only a small portion of the times impaired drivers are on the road.

Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicated that the estimated number of U.S. residents ages 16 years and older who drove under the influence in the past year was:

- 18.5 million for alcohol (7.2% of respondents ages 16 years and older),

- 11.7 million for marijuana (4.5% of respondents ages 16 years and older), and

- 2.4 million for illicit drugs other than marijuana (0.9% of respondents ages 16 years and older).15

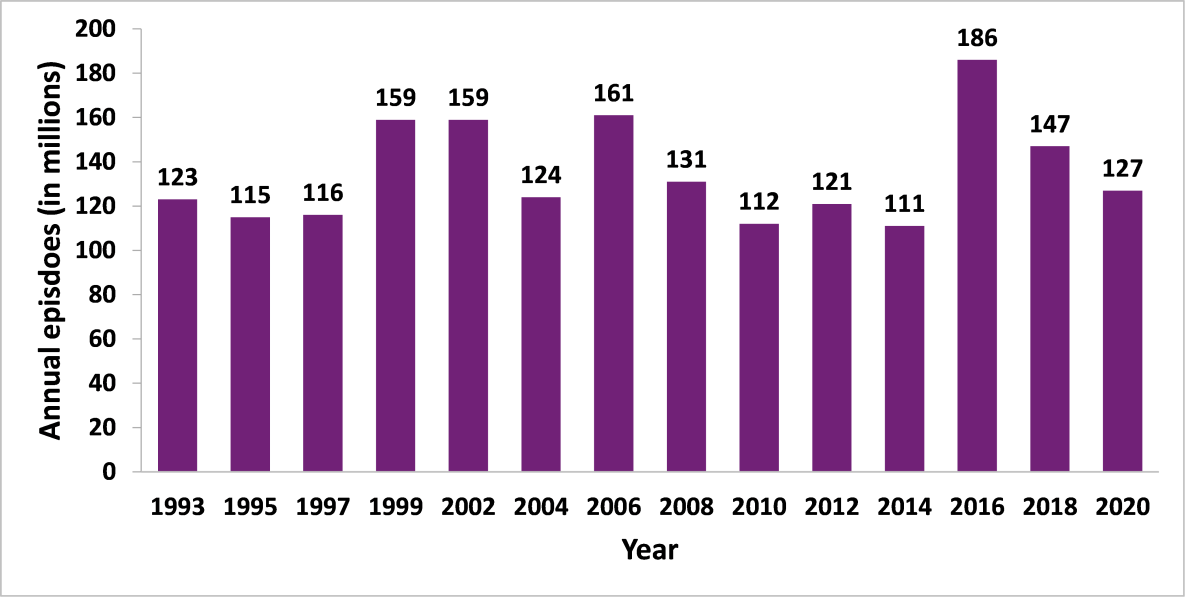

Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System indicated that 1.2% of adults drove after having too much to drink in the past 30 days in 2020. This resulted in an estimated 127 million episodes of alcohol-impaired driving among US adults.16

Annual Self-reported Alcohol-impaired Driving Episodes Among US Adults, 1993–2020

Source: CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 1993–2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss.

Note: Annual estimated alcohol-impaired driving episodes were calculated using BRFSS respondents’ answers to this question: “During the past 30 days, how many times have you driven when you’ve had perhaps too much to drink?” Annual estimates per respondent were calculated by multiplying the reported episodes during the preceding 30 days by 12. These numbers were summed to obtain the annual national estimates. (See Alcohol-impaired driving among adults—USA, 2014–2018 for more information).

Teen drivers and passengers

- Drinking any amount of alcohol before driving increases crash risk among teen drivers.17,18 Teen drivers have a much higher risk for being involved in a crash than older drivers at the same blood alcohol concentration (BAC), even at BAC levels below the legal limit for adults ages 21 years and older.18

- Among U.S. high school students who drove in 2019, about 5% drove after drinking alcohol in the prior 30 days.19 Also, among all high school students, about 17% rode with a driver who had been drinking alcohol in the prior 30 days.19

- Among U.S. high school students who drove in 2017, about 13% drove when they had been using marijuana in the prior 30 days.20,21

Young adult drivers

- Among drivers involved in fatal crashes in 2020, the percentage of drivers who were impaired by alcohol was highest among drivers 21–24 years old and 25–34 years old (26% each).1

- Adults ages 21–24 had the highest prevalence of driving after having too much to drink in the past 30 days (3.3%) when compared with all adults in 2018.22

Men

- Driving while impaired is more common among men. 22% of male drivers involved in fatal crashes were impaired by alcohol at the time of the crash compared with 16% for female drivers in 2020.1

- Self-reported driving under the influence of alcohol, marijuana, or illicit drugs is higher among men than women.3,19,22

American Indian and Alaska Native People

- Non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native people have the highest alcohol-impaired driving death rates among all racial and ethnic groups.23

- Alcohol-impaired driving death rates among non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native people are 2 to 11 times higher than other racial and ethnic groups in the United States.23

Motorcycle drivers

- A higher proportion of motorcyclists drive while impaired compared with drivers of other types of vehicles. For example, 27% of motorcycle drivers involved in fatal crashes in 2020 were impaired by alcohol, compared with 23% of passenger car drivers.1

Drivers who don’t always wear a seat belt

- Not always wearing a seat belt is more common among people who drive after drinking alcohol.19,22

- A higher percentage of alcohol-impaired drivers killed (66%)† were not wearing a seat belt compared with drivers with no alcohol in their system (44%), among all drivers killed in crashes in 2020.1

Drivers with prior DWI (driving while impaired) convictions

- The percentage of drivers with prior DWI convictions was four times higher among alcohol-impaired drivers involved in fatal crashes than among drivers with no alcohol in their system in 2020.1

What drivers can do

- Plan ahead. If you plan to drink alcohol or use drugs, make plans so that you do not have to drive.

- Get a ride home. If you have been drinking alcohol and/or using drugs, get a ride home with a driver who has not been drinking or using drugs, use a rideshare service, or call a taxi.

- Agree on a trusted designated driver ahead of time. If you are with a group, agree on a trusted designated driver in the group who will not drink alcohol or use drugs.

- Be aware of prescriptions and over-the-counter medicines. It’s not just alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drugs that can impair your ability to drive. Many types of prescription medicines and some over-the-counter medicines can also affect your ability to drive safely, either on their own or when combined with alcohol. Avoid driving if you are unsure how a medicine may affect you, if it has side effects that can harm your ability to drive, or if your doctor tells you not to drive after using a medicine.

What everyone can do

- Don’t let your friends drive while impaired by alcohol and/or drugs.

- Don’t ride with an impaired driver.

- If you’re hosting a party where alcohol or drugs will be available, remind your guests to plan ahead. Arrange for alternative transportation or agree on a trusted designated driver who will not drink alcohol or use drugs. Offer alcohol-free beverages, and make sure all guests leave with a driver who has not been drinking alcohol and/or using drugs.

- If you or someone you know is having trouble with alcohol or drugs, help is available.

- Always wear a seat belt on every trip—regardless of whether you’re the driver, the front seat passenger, or a back seat passenger. Wearing a seat belt reduces the risk of dying or being seriously injured in a crash by about half.24

Effective measures for preventing alcohol-impaired driving include:

Laws and enforcement

- Actively implementing and enforcing lower BAC limits.25

- Globally, most high-income countries have BAC laws set at 0.05 g/dl or lower,26,27 and these laws are effective for reducing crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers and deaths from these crashes.25 These laws serve as a general deterrent and reduce alcohol-impaired driving, even among drivers who are at highest risk of impaired driving.25

- Utah implemented a 0.05 g/dL BAC law in 2018; the other 49 states and the District of Columbia (DC) have a BAC limit of 0.08 g/dL.6,28 Utah’s 0.05 g/dL BAC law was associated with an 18% reduction in the motor vehicle crash death rate per mile driven in the first year after it went into effect. The new law was also associated with lower alcohol involvement in crashes.28

- An estimated 1,790 lives could be saved each year if all states adopted a 0.05 g/dl BAC limit.29

- Maintaining minimum legal drinking age laws and zero tolerance laws for drivers younger than 21 in all states.25,30,31

- Requiring alcohol ignition interlocks for all people convicted of alcohol-impaired driving, including first-time offenders.32 Additionally, incorporating alcohol use disorder assessment and treatment into interlock programs shows promise in reducing repeat offenses even after interlocks are removed.33

- Implementing publicized sobriety checkpoints30,34 and high-visibility saturation patrols.30

Screening, Assessment, and Treatment

- Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) can be beneficial for people who drink alcohol excessively but do not have alcohol use disorder. Brief interventions often involve assessing readiness, motivators, and barriers for behavior change. These types of interventions can also be delivered through technologies such as computers, cell phones, and tablets.25,35,36

- CDC’s Alcohol Screening Tool can be used by adults to assess their drinking and create a personal change plan.

- Implementing alcohol use disorder assessment and treatment, if needed, for people who are convicted of alcohol-impaired driving.25,30

Population-Level Strategies

- Supporting affordable alternative transportation options, such as nighttime and weekend public transportation hours.25

- Using strategies that increase the price of alcohol and make it less convenient to buy, such as increasing alcohol taxes and regulating alcohol outlet density. These strategies are effective for reducing drinking to impairment and also help to prevent alcohol-impaired driving.25,37–39

- Implementing programs that combine prevention efforts (such as sobriety checkpoints and limiting access to alcohol) with the involvement of a community coalition or task force.40

Technology

- The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) recommends that all new vehicles should be equipped with technology that prevents or limits the vehicle from operating if the driver is impaired by alcohol.41 The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law calls on the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to issue a Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard requiring all new passenger vehicles to come equipped with advanced technology for the prevention of impaired driving.42 This technology has significant potential to reduce impaired driving fatalities.25

Less is known about effective measures for the prevention of drug-impaired driving compared to alcohol-impaired driving.30 However, the following strategies are promising:

- Enforcement of drug-impaired driving laws.30

- Drug recognition experts (DREs) and law enforcement officers with Advanced Roadside Impaired Driving Enforcement (ARIDE) training are important to the enforcement of these laws. DREs are officers with specialized training who can recognize signs of impairment by alcohol and/or other substances.30

- Standardized toxicological testing of drivers, both those stopped for suspicion of impaired driving and those involved in fatal crashes.3,43

* In 2020 U.S. dollars

† These percentages are based on passenger vehicle occupants for which seat belt use/nonuse was known.

- What Works: Strategies to Reduce or Prevent Alcohol-Impaired Driving

- Sobering Facts: Alcohol-Impaired Driving State Fact Sheets

- Increasing Alcohol Ignition Interlock Use

- Impaired Driving: Publications

- Drug-Impaired Driving Fact Sheet [PDF – 2 pages]

- Marijuana and Public Health

- Motor Vehicle Prioritizing Interventions and Cost Calculator for States (MV PICCS)

- Teen Drivers and Passengers: Get the Facts

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS): Alcohol and drugs

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA): Drunk Driving

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA): Drug-Impaired Driving

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Countermeasures That Work: A Highway Safety Countermeasures Guide for State Highway Safety Offices, Tenth Edition, 2020 [PDF – 641 pages]

- The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) Findings for Motor Vehicle Injury

- CDC: WISQARS (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System)

- CDC: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)

- CDC: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA): Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS)

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Traffic Safety Facts 2020 Data: Alcohol-Impaired Driving (Report No DOT HS 813 294). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, National Center for Statistics and Analysis; April 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). WISQARS — Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2022.

- Azofeifa A, Rexach-Guzmán BD, Hagemeyer AN, Rudd RA, Sauber-Schatz EK. Driving Under the Influence of Marijuana and Illicit Drugs Among Persons Aged ≥16 Years — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(50):1153–1157.

- Berning A, Smither D. Traffic Safety Facts Research Note: Understanding the Limitations of Drug Test Information, Reporting, and Testing Practices in Fatal Crashes (DOT HS 812 072). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), National Center for Statistics and Analysis. April 2022.

- Thomas FD, Darrah J, Graham L, Berning A, Blomberg R, Finstad K, Griggs C, Crandall M, Schulman C, Kozar R, Lai J, Mohr N, Chenoweth J, Cunningham K, Babu K, Dorfman J, Van Heukelom J, Ehsani J, Fell J, Whitehill J, Brown T, Moore C. Alcohol and Drug Prevalence Among Seriously or Fatally Injured Road Users (Report No. DOT HS 813 399) [PDF – 73 pages]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), Office of Behavioral Safety Research. December 2022.

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI). Alcohol and Drugs. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute; 2022.

- Busardo FP, Pichini S, Pellegrini M, Montana A, Lo Faro AF, Zaami S, Graziano S. Correlation between Blood and Oral Fluid Psychoactive Drug Concentrations and Cognitive Impairment in Driving under the Influence of Drugs. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(1):84–96. doi:10.2174/1570159X15666170828162057

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence Review and Research Agenda. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2017.

- Compton R. Marijuana-Impaired Driving – A Report to Congress (Report No. DOT HS 812 440) [PDF – 44 pages]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA); July 2017.

- Hartman RL, Huestis MA. Cannabis effects on driving skills. Clin Chem. 2013;59(3):478–492. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2012.194381

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Medicines Risk Fact Sheet. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020.

- Lacey JH, Kelley-Baker T, Berning A, Romano E, Ramirez A, Yao J, Compton R. Drug and alcohol crash risk: A case-control study (Report No. DOT HS 812 355) [PDF – 190 pages]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; December 2016.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Crime in the United States 2018: Persons Arrested, Table 29 Estimated Number of Arrests—United States, 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigations, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Crime in the United States 2019: Persons Arrested, Table 29 Estimated Number of Arrests—United States, 2019. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigations, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2020 NSDUH Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. January 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Unpublished analyses, 2020 data.

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute. Fatality Facts 2020: Teenagers. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Highway Loss Data Institute; May 2022.

- Voas RB, Torres P, Romano E, Lacey JH. Alcohol-related risk of driver fatalities: an update using 2007 data. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(3):341–350. doi:10.15288/jsad.2012.73.341

- Yellman MA, Bryan L, Sauber-Schatz EK, Brener N. Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020;69(Suppl-1):77–83. doi:10.15585/mmwr.su6901a9

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, Ethier KA. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1

- Li L, Hu G, Schwebel DC, Zhu M. Analysis of US Teen Driving After Using Marijuana, 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2030473. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30473

- Barry V, Schumacher A, Sauber-Schatz E. Alcohol-impaired driving among adults—USA, 2014–2018. Inj Prev. 2022;28(3):211–217. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2021-044382

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Unpublished 2015–2019 data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, National Center for Statistics and Analysis; August 2022.

- Kahane CJ. Lives Saved by Vehicle Safety Technologies and Associated Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards, 1960 to 2012 – Passenger Cars and LTVs – With Reviews of 26 FMVSS and the Effectiveness Of Their Associated Safety Technologies in Reducing Fatalities, Injuries, and Crashes (Report No. DOT HS 812 069). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA); January 2015.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Accelerating Progress to Reduce Alcohol-Impaired Driving Fatalities. Getting to Zero Alcohol-Impaired Driving Fatalities: A Comprehensive Approach to a Persistent Problem. Negussie Y, Geller A, Teutsch SM, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2018.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on road safety 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Yellman MA, Sauber-Schatz EK. Motor Vehicle Crash Deaths — United States and 28 Other High-Income Countries, 2015 and 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(26):837–843. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7126a1

- Thomas FD, Blomberg R, Darrah J, Graham L, Southcott T, Dennert R, Taylor E, Treffers R, Tippetts S, McKnight S, Berning A. Evaluation of Utah’s .05 BAC per se law (Report No. DOT HS 813 233). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; February 2022.

- Fell JC, Scherer M. Estimation of the potential effectiveness of lowering the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limit for driving from 0.08 to 0.05 grams per deciliter in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:2128–2139. doi:10.1111/add.12365

- Venkatraman V, Richard CM, Magee K, Johnson K. Countermeasures That Work: A Highway Safety Countermeasures Guide for State Highway Safety Offices, 10th Edition, 2020 (Report No. DOT HS 813 097) [PDF – 641 pages]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA); July 2021.

- Guide to Community Preventive Services. CPSTF Findings for Motor Vehicle Injury: Reducing Alcohol-Impaired Driving. 2021.

- Guide to Community Preventive Services. Motor Vehicle Injury – Alcohol-Impaired Driving: Ignition Interlocks. 2021.

- Voas RB, Tippetts AS, Bergen G, Grosz M, Marques P. Mandating treatment based on interlock performance: evidence for effectiveness. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(9):1953–1960. doi:10.1111/acer.13149

- Guide to Community Preventive Services. Motor Vehicle Injury – Alcohol-Impaired Driving: Publicized Sobriety Checkpoint Programs. 2021.

- Tansil KA, Esser MB, Sandhu P, Reynolds JA, Elder RW, Williamson RS, Chattopadhyay SK, Bohm MK, Brewer RD, McKnight-Eily LR, Hungerford DW, Toomey TL, Hingson RW, Fielding JE; Community Preventive Services Task Force. Alcohol Electronic Screening and Brief Intervention: A Community Guide Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):801–811. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.013

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement – Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults: Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; November 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Preventing Excessive Alcohol Use. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022.

- Guide to Community Preventive Services. Alcohol – Excessive Consumption: Increasing Alcohol Taxes. 2021.

- Guide to Community Preventive Services. Alcohol – Excessive Use: Outlet Density. 2021.

- Shults RA, Elder RW, Nichols J, Sleet DA, Compton R, Chattopadhyay SK; Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Effectiveness of multicomponent programs with community mobilization for reducing alcohol-impaired driving. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(4):360–371. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.005

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). Safety Recommendation H-22-022. Washington, DC: National Transportation Safety Board. 2022.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- D’Orazio AL, Mohr ALA, Chan-Hosokawa A, Harper C, Huestis MA, Limoges JF, Miles AK, Scarneo CE, Kerrigan S, Liddicoat LJ, Scott KS, Logan BK. Recommendations for Toxicological Investigation of Drug-Impaired Driving and Motor Vehicle Fatalities—2021 Update. J Anal Toxicol. 2021;45(6):529–536. doi:10.1093/jat/bkab064