Distracted Driving

Nine people in the United States are killed every day in crashes that are reported to involve a distracted driver.1

Distracted driving is doing another activity that takes the driver’s attention away from driving. Distracted driving can increase the chance of a motor vehicle crash.

Anything that takes your attention away from driving can be a distraction. Sending a text message, talking on a cell phone, using a navigation system, and eating while driving are a few examples of distracted driving. Any of these distractions can endanger you, your passengers, and others on the road.

There are three main types of distraction:2

- Visual: taking your eyes off the road

- Manual: taking your hands off the wheel

- Cognitive: taking your mind off driving

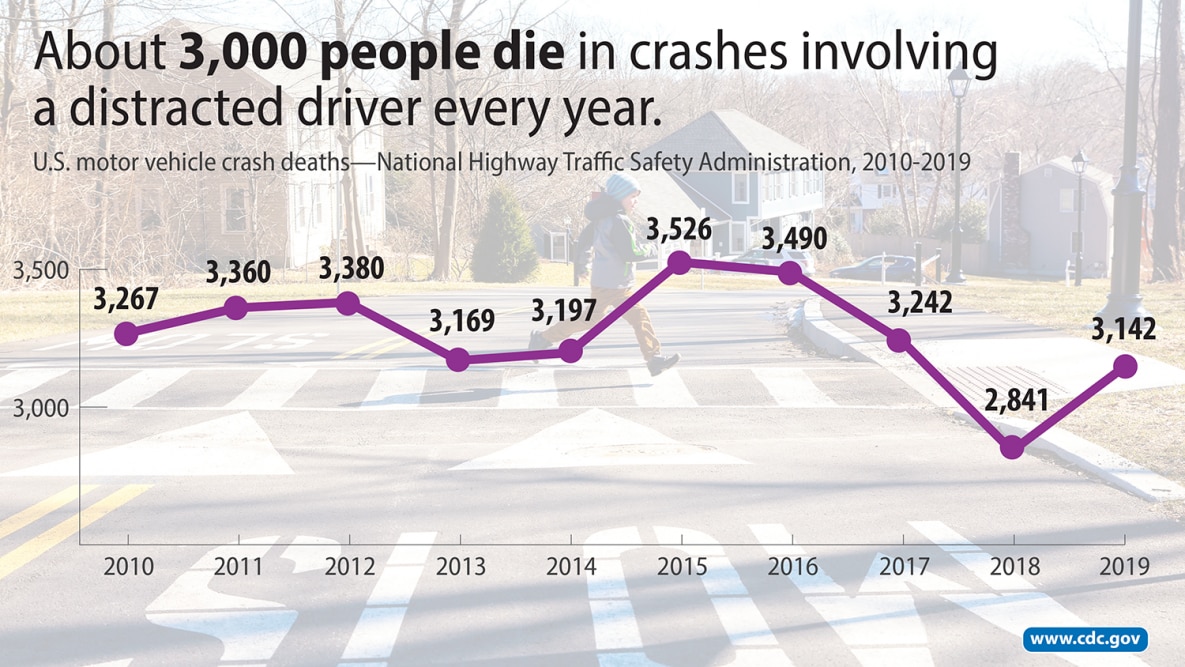

- In the United States, over 3,100 people were killed and about 424,000 were injured in crashes involving a distracted driver in 2019.1

- About 1 in 5 of the people who died in crashes involving a distracted driver in 2019 were not in vehicles―they were walking, riding their bikes, or otherwise outside a vehicle.1

Sources: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2010-2013, 2014–2018 and 2019

You can visit the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) website for more information on how data on motor vehicle crash deaths are collected and the limitations of distracted driving data.

Young adult and teen drivers

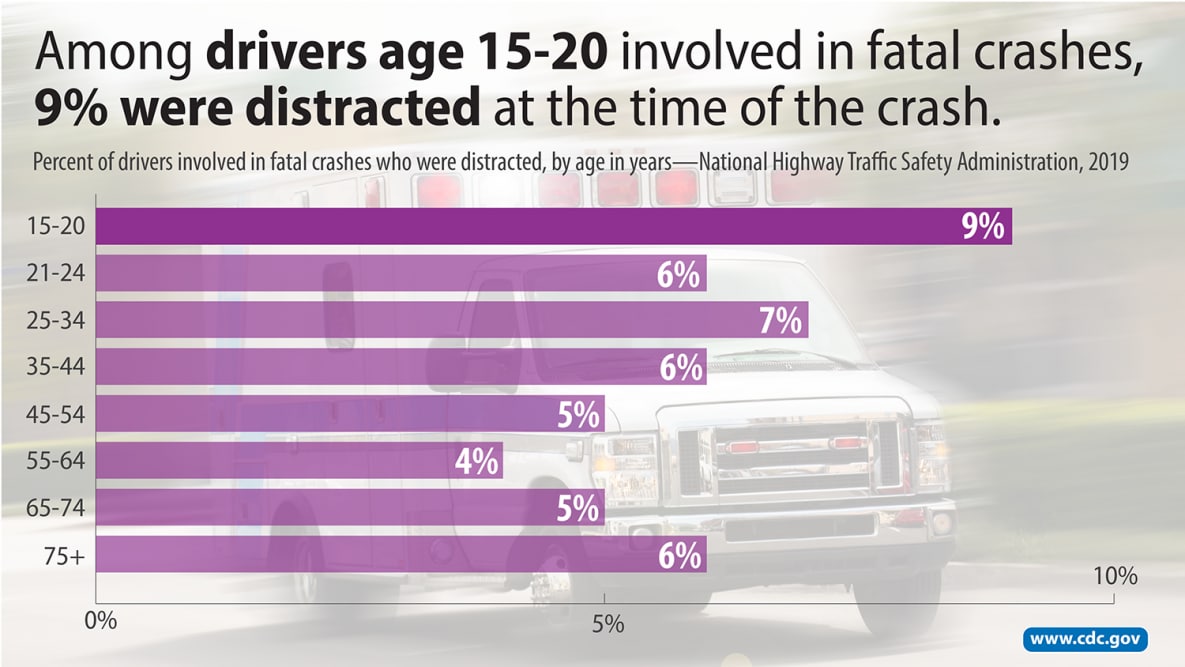

- Among fatal crashes involving distracted drivers in the U.S. in 2019:

- A higher percentage of drivers ages 15–20 were distracted than drivers age 21 and older.

- Among these younger drivers, 9% of them were distracted at the time of the crash.1

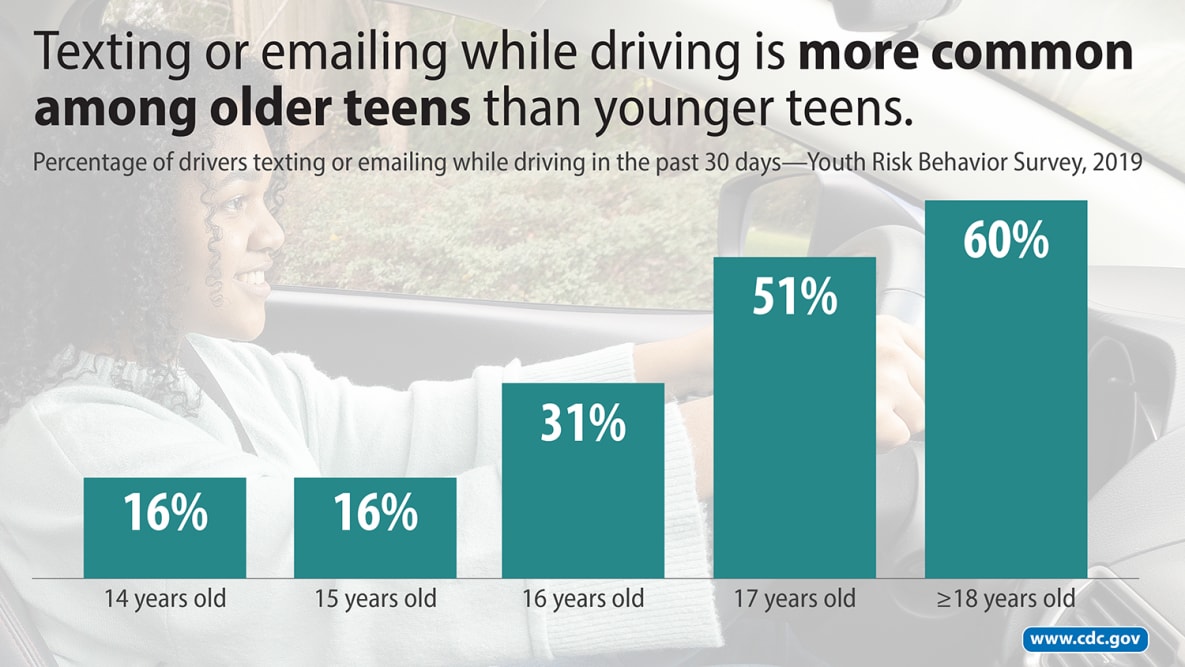

- A 2019 survey3 of U.S. high school students found:

- 39% of high school students who drove in the past 30 days texted or emailed while driving on at least one of those days.4

- Texting or emailing while driving was more common among older students than younger students (see figure below) and more common among White students (44%) than Black (30%) or Hispanic students (35%).4

- Texting or emailing while driving was as common among students whose grades were mostly As or Bs as among students with mostly Cs, Ds, or Fs. 4

- Students who texted or emailed while driving were also more likely to report other transportation risk behaviors. They were:

- more likely to not always wear a seat belt;

- more likely to ride with a driver who had been drinking alcohol; and

- more likely to drive after drinking alcohol. 4

Source: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2019

Source: Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

What drivers can do

- Do not multitask while driving. Whether it’s adjusting your mirrors, selecting music, eating, making a phone call, or reading a text or email―do it before or after your trip, not during.

- You can use apps to help you avoid cell phone use while driving. Consider trying an app to reduce distractions while driving.

What passengers can do

- Speak up if you are a passenger in a car with a distracted driver. Ask the driver to focus on driving.

- Reduce distractions for the driver by assisting with navigation or other tasks.

What parents can do5

- Talk to your teen or young adult about the rules and responsibilities involved in driving. Share stories and statistics related to teen/young adult drivers and distracted driving.

- Remind them driving is a skill that requires the driver’s full attention.

- Emphasize that texts and phone calls can wait until arriving at a destination.

- Familiarize yourself with your state’s graduated driver licensing system and enforce its guidelines for your teen.

- Know your state’s laws on distracted driving. Many states have novice driver provisions in their distracted driving laws. Talk with your teen about the consequences of distracted driving and make yourself and your teen aware of your state’s penalties for talking or texting while driving.

- Set consequences for distracted driving. Fill out CDC’s Parent-Teen Driving Agreement [PDF – 465 KB] together to begin a safe driving discussion and set your family’s rules of the road. Your family’s rules of the road can be stricter than your state’s law. You can also use these simple and effective ways to get involved with your teen’s driving: Parents Are the Key.

- Set an example by keeping your eyes on the road and your hands on the wheel while driving.

- Learn more: visit NHTSA’s website on safe teen driving.

- Many states have enacted laws to help prevent distracted driving. These include banning texting while driving, implementing hands-free laws, and limiting the number of young passengers who can ride with teen drivers.

- The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety tracks cell phone use laws and young passenger restrictions by state.

- While the effectiveness of cell phone and texting laws requires further study, high-visibility enforcement (HVE) efforts for distracted driving laws can be effective in reducing cell phone use while driving. From 2010 to 2013, NHTSA evaluated distracted driving HVE demonstration projects in four communities. These projects increased police enforcement of distracted driving laws and increased awareness of distracted driving using radio advertisements, news stories, and similar media. After the projects were complete, observed driver cell phone use fell from:

- 4.1% to 2.7% in the Sacramento Valley Region in California,6

- 6.8% to 2.9% in Hartford, Connecticut,7

- 4.5% to 3.0% in the state of Delaware,6 and

- 3.7% to 2.5% in Syracuse, New York.7

- Graduated driver licensing (GDL) is a system which helps new drivers gain experience under low-risk conditions by granting driving privileges in stages. Comprehensive GDL systems include five components8-9, one of which addresses distracted driving: the young passenger restriction.10 CDC’s GDL Planning Guide [PDF – 3 MB] can assist states in assessing, developing, and implementing actionable plans to strengthen their GDL systems.

- Some states have installed rumble strips on highways to alert drowsy, distracted, or otherwise inattentive drivers that they are about to go off the road. These rumble strips are effective at reducing certain types of crashes.10

- CDC has developed the Parents Are the Key campaign, which helps parents, pediatricians, and communities help keep teen drivers safe on the road.

- In 2022, the U.S. Department of Transportation released the National Roadway Safety Strategy [PDF – 42 pages]. Part of the strategy includes supporting vehicle technology systems that detect distracted driving.

- In 2021, Congress provided resources to add distracted driving awareness as part of driver’s license exams as part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law [PDF – 1039 pages].

- Several federal regulations target distractions for workers:

- In 2009, President Obama issued an Executive Order prohibiting federal employees from texting while driving government-owned vehicles or when driving privately owned vehicles on official government business.

- In 2010, the Federal Railroad Administration banned cell phone and electronic device use for railroad operating employees on the job.

- In 2010, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration banned commercial vehicle drivers from texting while driving.

- In 2011, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration banned all hand-held cell phone use by commercial drivers and drivers carrying hazardous materials.

- NHTSA has several campaigns to raise awareness of the dangers of distracted driving, including their annual “U Drive. U Text. U Pay.” campaign, which began in April 2014.

- NHTSA has issued voluntary guidelines to promote safety by discouraging the introduction of both original, in-vehicle [PDF – 177 pages] and portable/aftermarket [PDF – 96 pages] electronic devices in vehicles.

This fact sheet provides an overview of distracted driving and promising strategies that are being used to address distracted driving.

- CDC MMWR – Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

- CDC MMWR – Mobile Device Use While Driving — United States and Seven European Countries, 2011

- NHTSA – Distracted Driving

- Governors Highway Safety Association – Distracted Driving

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety – Distracted Driving

- World Health Organization – Mobile Phone Use: A Growing Problem of Driver Distraction

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) – Distracted Driving at Work

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) – Campaign Materials

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2021). Traffic Safety Facts Research Note: Distracted Driving 2019 (DOT HS 813 111). Department of Transportation, Washington, DC: NHTSA. Accessed 8 February 2022.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2010). Overview of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Driver Distraction Program (DOT HS 811 299) [PDF – 36 pages]. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC. Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Yellman, M.A., Bryan, L., Sauber-Schatz, E.K., Brener, N. (2020). Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl,69(Suppl-1),77–83.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Teen Driving. Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Chaudhary, N.K., Connolly, J., Tison, J., Solomon, M., & Elliott, K. (2015). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Evaluation of the NHTSA Distracted Driving High-Visibility Enforcement Demonstration Projects in California and Delaware [PDF – 72 pages] (DOT HS 812 108). U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC.

- Chaudhary, N.K., Casanova-Powell, T.D., Cosgrove, L., Reagan, I., & Williams, A. (2012). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Evaluation of NHTSA Distracted Driving Demonstration Projects in Connecticut and New York [PDF – 80 pages] (DOT HS 811 635). U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Motor Vehicle Injuries. Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Venkatraman, V., Richard, C. M., Magee, K., & Johnson, K. (2021). Countermeasures that work: A highway safety countermeasures guide for State Highway Safety Offices, 10th edition, 2020 (Report No. DOT HS 813 097) [PDF – 641 pages]. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC.

- Federal Highway Administration. (2011). Technical Advisory: Shoulder and Edge Line Rumble Strips (T 5040.39, Revision 1) [PDF – 9 pages]. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC: FHWA. Accessed 24 August 2020.