Key points

- Screening for critical congenital heart defects (CCHDs) can help identify some babies with a CCHD before they go home from the birth hospital.

- Screening allows babies to be treated early and may prevent disability or death early in life.

Importance of screening

Newborn screening may identify critical congenital heart defects (CCHDs) before signs are evident. Identifying newborns with these conditions before hospital discharge can help ensure they receive prompt care and treatment. Timely care may prevent disability or death early in life.

Screening has prevented early infant death

Screening guidelines

Current recommendations focus on screening healthy-appearing newborns in:

- Newborn nurseries

- Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or other settings after the child has been weaned off supplemental oxygen

Screening is done when a baby is at least 24 hours of age or as late as possible if the baby is to be discharged before 24 hours of age. Timing the screening around the time of the newborn hearing screening can help improve efficiency. A pulse oximeter is used to measure the percentage of hemoglobin in the blood that is saturated with oxygen.

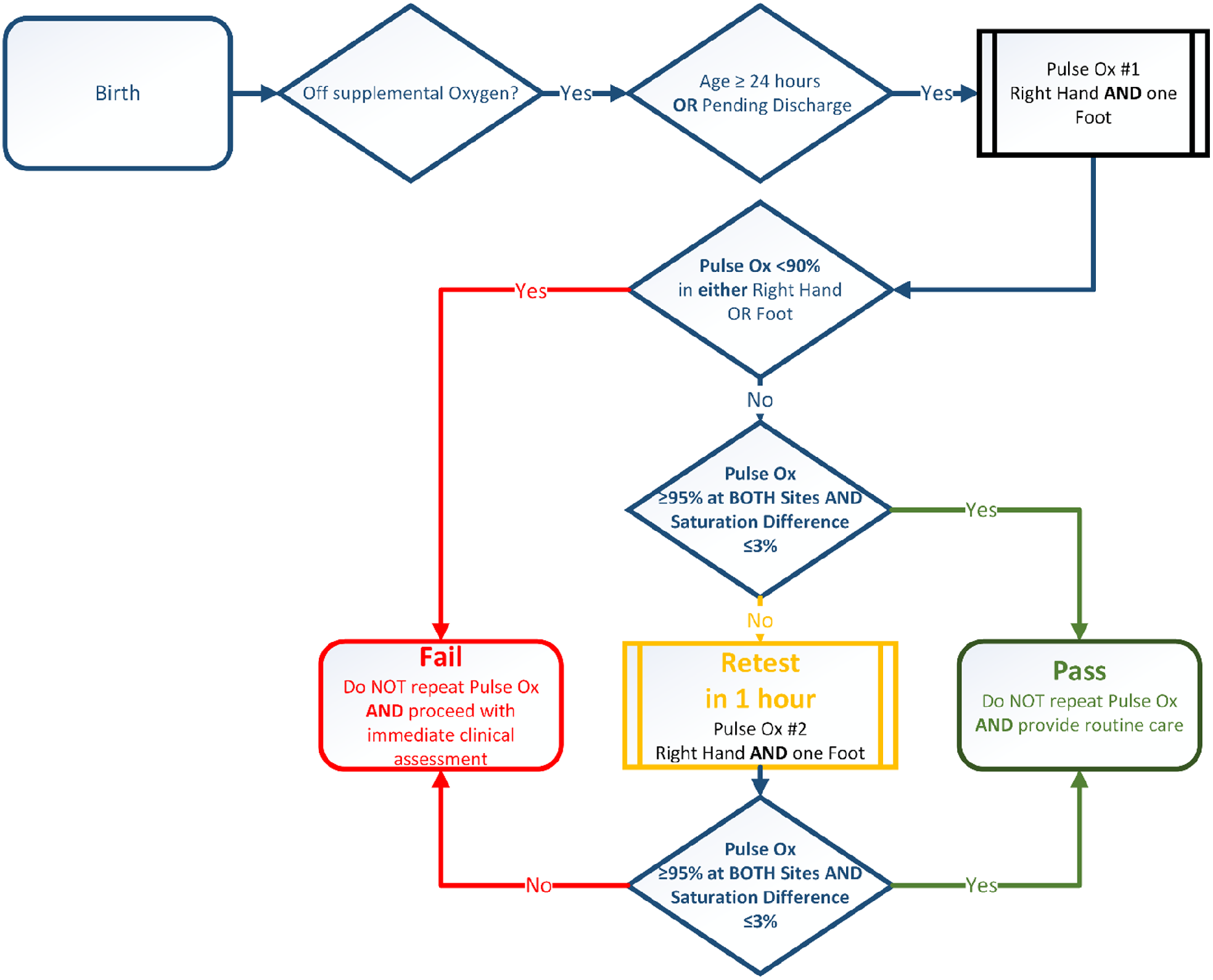

The following is the recommended algorithm, for newborn screening for critical congenital heart disease using pulse oximetry (Oster et al., 2025)

Pulse oximetry screening should not replace taking a complete family health history, pregnancy history, or physical examination. These exams may detect CCHDs before the development of low oxygen levels (hypoxemia) in the blood. Screening with pulse oximetry identifies several types of CCHDs, the most common are below.

Screening targets

Screening with pulse oximetry can identify a number of types of CCHDs, the most common of which are shown below. While not the main targets of screening, many conditions other than CCHDs may present with hypoxemia. As a result, such conditions may also be detected via pulse oximetry.

Critical Congenital Heart Defects

- Coarctation of the aorta and Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- Double outlet right ventricle, Ebstein anomaly, and Single ventricle

- Interrupted aortic arch and Tetralogy of Fallot

- Pulmonary atresia and Total anomalous pulmonary venous return

- d-Transposition of the great arteries

- Tricuspid artresia and Truncus ateriosus

- Other critical defects not otherwise specified

Other conditions that are not CCHDs

- Hemoglobinopathy

- Hypothermia

- Infection, including sepsis

- Lung disease (congenital or acquired)

- Non-critical congenital heart defect

- Persistent pulmonary hypertension

- Other hypoxic conditions not otherwise specified

Screening outcomes

Failed screens

A screen is considered failed if at least one of these occur:

- Any oxygen (O2) saturation measure is <90% in either the right hand or foot (initial screen/repeat screen)

- O2 saturation is <95% in either the right hand or foot on 2 measures*

- A >3% difference in O2 saturation between the right hand and foot on 2 measures*

*Each separated by one hour

Any infant who fails the screen should have an evaluation for causes of hypoxemia. In most cases this will include an echocardiogram. If a reversible cause of hypoxemia is identified and appropriately treated, an echocardiogram may not be necessary. The infant's pediatrician should be notified immediately and the infant might need to be seen by a cardiologist.

Passed screens

A screen is considered passed when there is an oxygen saturation measure that is:

- ≥95% in BOTH the right hand and foot

- ≤3% absolute difference between the right hand and foot

When the above conditions are met, screening would end. Pulse oximetry screening does not detect all CCHDs. Therefore, it is possible for a baby with a passing screening result to still have a CCHD or other congenital heart defect.

Ways to reduce false positive screens

- Screen the newborn while he or she is alert.

- Screen the newborn when he or she is at least 24 hours old.

- Screen the newborn after he or she has been weaned off supplemental O2.

Resources

Online resources

American Academy of Pediatrics: Newborn Screening for Critical Congenital Heart Defect (CCHD) . This online resource provides medical staff with comprehensive instructions on how to perform newborn screening for CCHD.

Children's National Medical Center's Congenital Heart Disease Screening Program has created videos about critical CHD screening for parents and healthcare professionals.

Congenital Heart Public Health Consortium (CHPHC). CHPHC's website provides resources for families and providers on heart defects and screening.

NewSTEPS. This webpage on CCHDs provides a central location for resources related to these conditions, including webinars, legislative updates, and news.

Publications

Evidence review: Critical congenital cyanotic heart disease

- Dawson AL, Cassell CH, Riehle-Colarusso T, Grosse SD, Tanner JP, Kirby RS, Watkins SM, Correia JA, Olney RS. Factors associated with late detection of critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2013; 132: e604-11.

- Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, Honein MA, Oster ME. Estimated Number of Infants Detected and Missed by Critical Congenital Heart Defect Screening. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):1000-1008.

- Peterson C, Dawson A, Grosse SD, Riehle-Colarusso T, Olney RS, Tanner JP, Kirby RS, Correia JA, Watkins SM, Cassell CH. Hospitalizations, costs, and mortality among infants with critical congenital heart disease: How important is timely detection? Birth Def Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2013;97(10):664-72.

- Mahle WT, Newburger JW, Matherne GP, Smith FC, Hoke TR, Koppel R, Gidding SS, Beekman RH 3rd, Grosse SD. American Heart Association Congenital Heart Defects Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Role of pulse oximetry in examining newborns for congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the AHA and AAP. Pediatrics. 2009; 124:823-36.

- De-Wahl Granelli A, Wennergren M, Sandberg K, Mellander M, Bejlum C, Inganas L, Eriksson M, Segerdahl N, Agren A, Ekman-Joelsson BM, Sunnegardh J, Verdicchio M, Sotman-Smith I. Impact of pulse-oximetry screening on the detection of duct-dependent congenital heart disease: a Swedish prospective screening study in 39,821 newborns. BMJ. 2009; 338:a3037.

- Peterson C, Gross SD, Glidewell J, Garg LF, Van Naarden Braun K, Knapp MM, Beres LM, Hinton CF, Olney RS, Cassell CH. A public health economic assessment of hospitals' cost to screen newborns for critical congenital heart disease. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1):86-93.

- Peterson C, Grosse SD, Oster ME, Olney RS, Cassell CH. Cost-effectiveness of routine screening for critical congenital heart disease in US newborns. Pediatrics. 2013; 132:e595-603.

- Grosse SD, Abouk R, Glidwell J, Oster ME. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2017; 3, 34.

- Abouk R, Grosse SD, Ailes EC, Oster ME. Association of US State Implementation of Newborn Screening Policies for Critical Congenital Heart Disease With Early Infant Cardiac Deaths. JAMA. 2017; 318(21): 2111-2118.