Key points

- Tricuspid atresia (pronounced try-CUSP-id uh-TREE-zhuh) is a congenital heart defect. Congenital means present at birth.

- It occurs when the tricuspid valve in the heart does not form at all.

- Surgical repairs for tricuspid atresia aren't a cure.

- People with this condition should schedule routine checkups with a heart doctor to stay as healthy as possible.

What it is

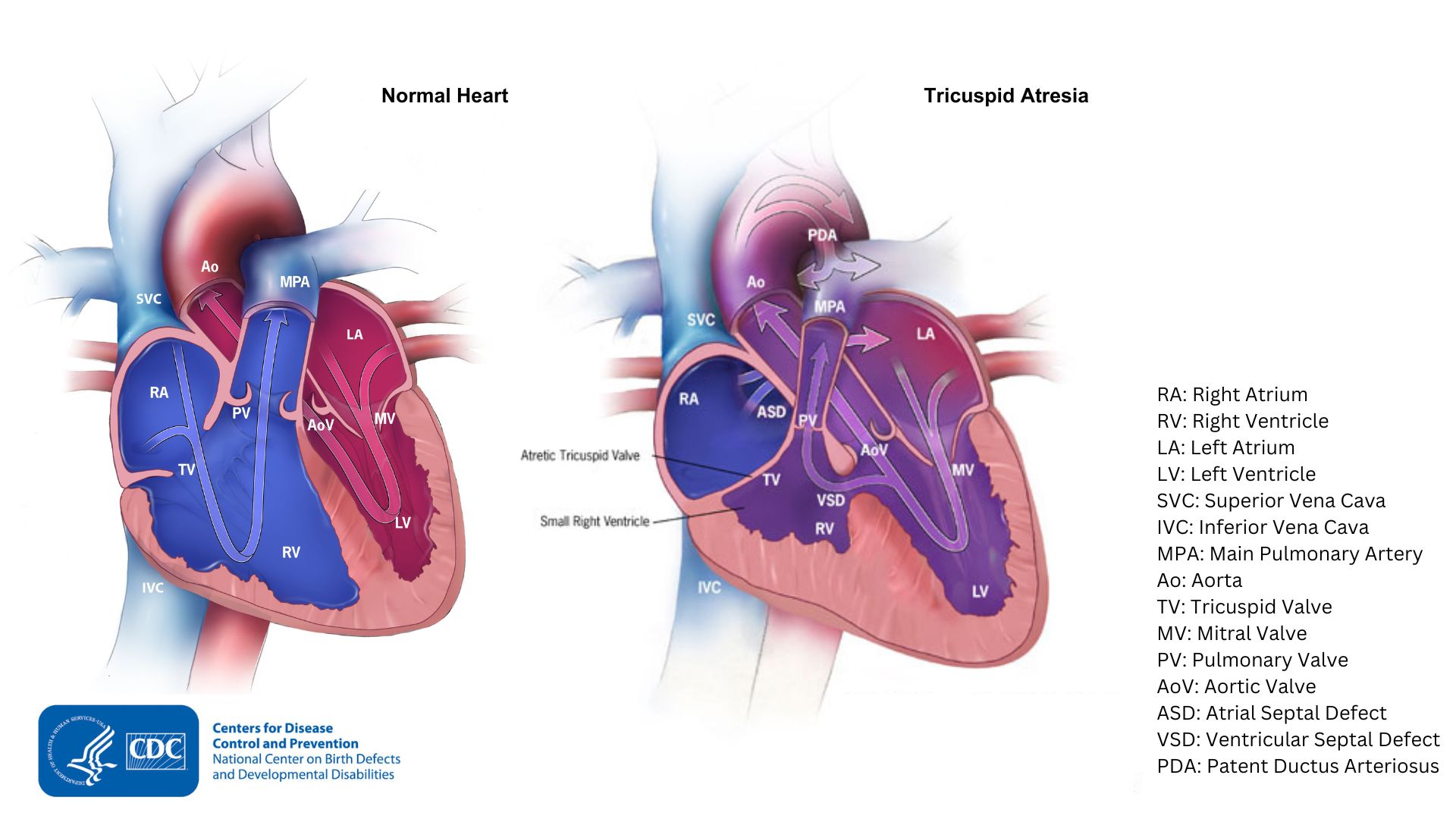

Tricuspid atresia occurs when the tricuspid valve in the heart does not form at all. The tricuspid valve controls blood flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle. The right atrium is the upper right chamber of the heart. The right ventricle is the lower right chamber of the heart.

In babies with tricuspid atresia, blood can’t flow correctly through the heart and to the rest of the body. Blood is unable to get from the right atrium through the right ventricle and out to the lungs. For this reason, the right ventricle can be underdeveloped. The main pulmonary artery may also be small with very little blood going through it to the lungs.

A baby with tricuspid atresia may need surgery or other procedures soon after birth. Therefore, tricuspid atresia is considered a critical congenital heart defect (critical CHD).

Occurrence

About 1 in 12,500 (about 296) babies in the United States are born with tricuspid atresia each year.

Signs and symptoms

Babies born with tricuspid atresia will show symptoms at birth or very soon afterwards. They may have a bluish skin color, called cyanosis, because their blood doesn't carry enough oxygen. Infants with tricuspid atresia can have additional symptoms such as:

- Problems breathing

- Ashen or bluish skin color

- Poor feeding

- Extreme sleepiness

Complications

In tricuspid atresia, blood cannot flow directly from the right atrium to the right ventricle. Therefore, blood must use other routes to bypass the unformed tricuspid valve. Babies born with tricuspid atresia often also have the following defects:

- Atrial Septal Defect: A hole between the right and left atria.

- Ventricular Septal Defect: A hole between the right and left ventricles.

These defects allow oxygen-rich blood to mix with oxygen-poor blood. This helps oxygen-rich blood has a way to get pumped to the rest of the body.

Doctors may give a baby medicine to keep the baby's ductus arteriosus (PDA in the image) open after birth. The ductus arteriosus is the blood vessel that allows blood to move around the baby's lungs before the baby is born. This blood vessel usually closes after birth. When the ductus arteriosus doesn't close, it is referred to as patent ductus arteriosus. Keeping this connection open helps blood get to the lungs for oxygen and bypass the small right side of the heart.

Some babies with tricuspid atresia may also have dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries (d-TGA). In d-TGA, the main connections (arteries) from the heart are reversed. The main pulmonary artery now arises from the left side. It carries oxygen-rich blood returning from the lungs back to the lungs. The main pulmonary artery normally carries oxygen-poor blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs. The aorta now arises from the right side and carries oxygen-poor blood back out to the body. The aorta normally carries blood from the left side of the heart to the body,

When a baby has both tricuspid atresia and d-TGA, blood is able to get to the lungs. This is because the main pulmonary artery arises from the developed left ventricle. However, blood cannot get out to the body because the aorta arises from the poorly formed, small right ventricle.

Risk factors

The causes of tricuspid atresia among most babies are unknown. Some babies have heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. A combination of genes and other risk factors may increase the risk for tricuspid atresia. These factors can include things in a mother's environment, what she eats or drinks, or the medicines she uses.

Testing and diagnosis

Tricuspid atresia may be diagnosed during pregnancy or soon after a baby is born.

During pregnancy

During pregnancy, screening tests (prenatal tests) check for birth defects and other conditions. An ultrasound, a tool that creates pictures of the baby, may detect tricuspid atresia. If the health care provider suspects tricuspid atresia, they can request a fetal echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis. A fetal echocardiogram is a more detailed ultrasound of the baby's heart. This test can show problems with:

- The structure of the heart

- The major blood vessels

- How the heart is working with this defect.

After the baby is born

Babies born with tricuspid atresia will show symptoms at birth or very soon afterwards. During a physical examination, a doctor can see the symptom or hear a heart murmur when listening with a stethoscope. A heart murmur is an abnormal "whooshing" sound caused by blood not flowing properly.

If a murmur is heard or other symptoms are present, the healthcare provider might request additional tests to confirm the diagnosis. The most common test is an echocardiogram, which is an ultrasound of the heart. Cardiac catheterization is inserting a thin tube into a blood vessel and guiding it to the heart. Cardiac catheterization can confirm the diagnosis by looking at the inside of the heart and measuring the blood pressure and oxygen. Other tests to make the diagnosis include an electrocardiogram (EKG), chest X-rays, and other medical tests.

Tricuspid atresia can also be detected with newborn pulse oximetry screening. Newborn screening using pulse oximetry can identify some infants with tricuspid atresia before they show any symptoms.

Treatments

Medicines

Some babies and children will need medicines to help:

- Strengthen the heart muscle

- Lower their blood pressure

- Help the body get rid of extra fluid

Nutrition

Some babies with tricuspid atresia become tired while feeding and do not eat enough to gain weight. To make sure babies have a healthy weight gain, a special high-calorie formula might be prescribed. Some babies become extremely tired while feeding and might need to be fed through a feeding tube.

Surgery

Surgical treatment for tricuspid atresia depends on its severity and presence of other heart defects. Soon after birth, one or more surgeries may be needed. The surgeries will help increase blood flow to the lungs and bypass the poorly functioning right side of the heart.

Other surgeries or procedures may be needed later. These surgeries, described below, do not cure tricuspid atresia, but they help restore heart function. Sometimes medicines are given to help treat symptoms of the defect before or after surgery.

Septostomy. A septostomy may be done within the first few days or weeks of a baby's life. The procedure creates or enlarges the atrial septal defect, the hole between the right and left upper chambers (atria). This allows oxygen-poor blood to mix with oxygen-rich blood, so that more oxygen-rich blood can get to the body.

Banding. If the baby has other heart defects along with tricuspid atresia, there may be too much blood flowing to the lungs. Thus, not enough blood can go out to the rest of the body. Too much blood in the lungs can damage them. If this is the problem, surgery may be done early in life. The surgeon will place a band around the main pulmonary artery going to the lungs. This will help control blood flow to the lungs. This banding is a temporary procedure and will likely be removed.

Shunt Procedure. This surgery usually is done within the first 2 weeks of a baby’s life. Surgeons create a bypass (shunt) from the aorta to the main pulmonary artery, allowing blood to get to the lungs. If the aorta is small (i.e. baby also has d-TGA), the surgeon will also enlarge the aorta at this time. After this procedure, an infant's skin still might look bluish because oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood still mix in the heart.

Bi-directional Glenn Procedure. This usually is performed when an infant is 4 to 6 months of age. This procedure creates a direct connection between the main pulmonary artery and the superior vena cava. The superior vena cava is the vessel returning oxygen-poor blood from the upper part of the body to the heart. This allows blood returning from the body to flow directly to the lungs and bypass the heart.

Fontan Procedure. This procedure usually is done around 2 years of age. Doctors connect the main pulmonary artery and the inferior vena cava. The inferior vena cava returns oxygen-poor blood from the lower part of the body to the heart. This allows the rest of the blood coming back from the body to go to the lungs. After surgery, oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood no longer mix in the heart and an infant’s skin will no longer look bluish.

What to expect long-term

Infants who have these surgeries are not cured; they might have lifelong complications. If the tricuspid atresia is very complex, or the heart becomes weak after the surgeries, a heart transplant might be needed. Children who receive a heart transplant will need to take medicines for the rest of their lives. The medicines help prevent rejection of the new heart.

Babies born with tricuspid atresia will need regular follow-up visits with a cardiologist (a heart doctor). These visits can help monitor their progress and check for other health conditions that might develop as they get older. As adults, they may need more surgery or medical care for other possible problems.