Connecting Networks to Solve the Mystery of Zika

April 30, 2019

GUATEMALA: Nurse Karen Orozco loading new tablets for capturing data on febrile illness patients as part of a community surveillance study. Photo: Joe P. Bryan

In 2014, when the Zika virus (ZIKV) emerged as a global public health threat, nine countries were particularly well poised to respond.

CDC country offices in China, Egypt, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Kenya, South Africa, and Thailand, were working on or setting up activities to conduct surveillance on acute febrile illness (AFI). These country offices, as well as Peru, which has a partnership with the U.S. Navy, analyzed and interpreted the AFI data and used it to develop and implement strategies to protect people’s health and improve their well-being.

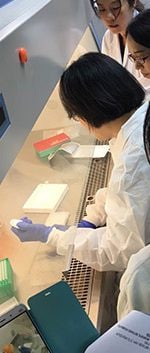

CHINA: Training on the AFI Taq Man Array card—by Liu Jie from UVA—in Guangzhou, Guangdong CDC. The card was used to test for multiple pathogens from blood samples collected from patients enrolled at each of the five AFI sentinel surveillance hospitals. Photo: Zhang Yuzhi

These AFI surveillance activities used data from local health centers and hospitals to identify and characterize sources of fever, one of the major symptoms of ZIKV infection. Using existing or new AFI surveillance systems and working with local officers, CDC was able to rapidly form a worldwide surveillance network across four continents to examine the global distribution of ZIKV.

In addition to not having to create a new global ZIKV surveillance system, CDC and its partners also leveraged existing activities in the nine countries to conduct research to evaluate two new laboratory tests for ZIKV.

LEVERAGING EXISTING PLATFORMS

KENYA: Rapid diagnostic tests were set up for AFI laboratory testing (bottom right, next to the white box). Photo: Nailah Smith

The work conducted allowed for the quick identification and characterization of some of the first ZIKV cases in Guatemala and India. In countries like Thailand, where ZIKV had been circulating for years, monitoring for adverse health effects and trends of the virus helped develop recommendations for public health activities and interventions. In countries where mosquito- or tick-borne virus (including ZIKV, dengue, and yellow fever) circulation is common, the public health research activities offered the opportunity for rapid evaluation of new ZIKV laboratory tests. Thanks to this worldwide network, experts quickly gained a better understanding of who got infected and why, health risks to local populations and travelers, and possible regional differences in disease outcomes. They also discovered causes of unknown fevers across the world and were able to use this new information to adapt and strengthen surveillance and laboratory systems, further advancing global health security.

The success of harnessing the AFI surveillance activities to study ZIKV underscores the benefits of regional coordination of surveillance and research, and highlights the value of using existing globally connected surveillance systems as a platform to study and respond to emerging disease threats faster and smarter than ever before. In a world where a disease can circle in the globe in a matter of hours, it is vital to have global networks of scientists who can unravel the mysteries of new diseases and develop solutions to them just as quickly.