* Beginning in 2014, a competitive insurance marketplace will be set up in the form of state-based insurance exchanges. These exchanges will allow eligible persons and small businesses with up to 100 employees to purchase health insurance plans that meet criteria outlined in the Affordable Care Act (ACA §1311). If a state does not create an exchange, the federal government will run one in that state.

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Tobacco Use Screening and Counseling During Physician Office Visits Among Adults — National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005–2009

Corresponding author: Ahmed Jamal, MBBS, Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, 3005 Chamblee Tucker Rd, MS K-50, Atlanta, GA 30341. Telephone: 770-488-5077; Fax: 770-488-5848; E-mail: jze1@cdc.gov.

Introduction

Tobacco use continues to be the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States; cigarette smoking accounts for approximately 443,000 premature deaths annually (1). In 2009, the prevalence of smoking among U.S. adults was 20.6% (46 million smokers), with no significant change since 2005 (20.9%) (2). In 2010, approximately 69% of smokers in the United States reported that they wanted to quit smoking (3). Approximately 44% reported that they tried to quit in the past year for ≥1 day; however, only 4%–7% were successful each year (4). Tobacco dependence has many features of a chronic disease: most patients do not achieve abstinence after their first attempt to quit, they have periods of relapse, and they often require repeated cessation interventions (4). At least 70% of smokers visit a physician each year, and other smokers visit other health-care professionals, providing key opportunities for intervention (4). The 2008 update to the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence recommends that clinicians and health-care delivery systems consistently identify and document tobacco use status and treat every tobacco user seen in a health-care setting using the 5 A's model: 1) ask about tobacco use, 2) advise tobacco users to quit, 3) assess willingness to make a quit attempt, 4) assist in quit attempt, and 5) arrange for follow-up (4). The PHS guideline also recommends the following as effective methods for increasing successful cessation attempts: individual, group, and telephone counseling; any of the seven first-line medications for tobacco dependence that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); and provision of coverage for these treatments by health-care systems, insurers, and purchasers (4). However, clinicians and health-care systems often do not screen for and treat tobacco use consistently and effectively (4).

The Healthy People 2020 objectives for health systems changes related to tobacco cessation include increasing tobacco screening in office-based ambulatory care settings to 68.6% from a baseline of 62.4% among persons aged ≥18 years in 2007 (objective TU 9.1) and increasing tobacco cessation counseling in office-based ambulatory care settings to 21.1% from a baseline of 19.2% among current tobacco users aged ≥18 years in 2007 (objective TU 10.1) (5). An overall Healthy People 2020 objective for adult cessation is increasing recent (i.e., within the past year) smoking cessation success by adult smokers to 8.0% among adults aged ≥18 years who have ever smoked 100 cigarettes, who do not smoke now, and who last smoked ≤1 year ago and among current smokers who initiated smoking at least 2 years ago from a baseline of 6.0% among adults aged ≥18 years in 2008 who ever smoked 100 cigarettes, who do not smoke now, and who last smoked ≤1 year ago and among current smokers who initiated smoking at least 2 years ago (objective TU 5.1) (5).

This report summarizes data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) that address the three Healthy People 2020 objectives (increase screening, increase cessation counseling, and increase overall cessation success) and tobacco medication provision by patient- and physician-related characteristics and presents trends in recent successful cessation among adult smokers by whether they visited a doctor in the past year. These results can be used by researchers and health-care providers to track and improve adherence to the PHS clinical practice guideline on tobacco use and to learn of opportunities for tobacco cessation as a covered health benefit.

Methods

To estimate the percentage of office-based physician visits made by adults aged ≥18 years with documentation of screening for tobacco use, tobacco cessation counseling in the form of health education ordered or provided during those visits, as well as tobacco cessation medications ordered or continued during those visits, CDC analyzed data from the combined 2005–2008 NAMCS. NAMCS is a national probability sample survey of outpatient visits made to office-based physicians that measures health-care use across various health-care providers.

The NAMCS sample included 96,232 outpatient visits among persons aged ≥18 years, ranging from 21,220 visits in 2005 to 27,169 in 2007. The NAMCS estimates for tobacco use screening and tobacco cessation counseling and medications among visits by adults aged ≥18 years were analyzed by patient demographics, tobacco use status, type of health insurance, counseling and education provided, medication continued or ordered, and other physician- or visit-related characteristics. Demographic characteristics include age, sex, and race/ethnicity; length of visit; and type of health insurance (private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid or State Children's Health Insurance Program [SCHIP], self-pay, or other [workers' compensation; no charge or charity; other sources of payment not covered by private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid/SCHIP, workers' compensation, self-pay, and no charge or charity; or unknown]). Physician-related characteristics include practice type (solo or other), specialty, and whether the physician was the patient's primary care physician (determined by response to the question, "Are you the patient's primary care physician/provider?").

For the 2005–2007 NAMCS, respondents who were eligible both for Medicare and Medicaid were categorized as Medicaid recipients for type of health insurance; however, these respondents were classified as Medicare recipients in 2008. To account for this change, the 2005–2007 payment type variable was recoded to be consistent with the 2008 classification for primary expected source of payment. For all survey years, nonphysician providers, federally employed physicians, and physicians in anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology specialties were excluded. The basic sampling unit for NAMCS is the physician-patient encounter or office visit. For physicians whose major professional activity was patient care, only visits classified by the American Medical Association or the American Osteopathic Association as office-based, patient care were included. The survey methods and sampling frame has been described elsewhere (available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_scope.htm#namcs_scope). Additional information on the NAMCS microdata file documentation also is available (ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NAMCS).

NAMCS defines tobacco use as documentation in the medical chart that the patient is a current user of tobacco, including cigarettes or cigars, snuff, or chewing tobacco. Tobacco cessation counseling is defined as information given in the form of health education to the patient on topics related to tobacco use in any form, including cigarettes, cigars, snuff, and chewing tobacco, or on exposure to secondhand smoke. Tobacco cessation counseling includes information on smoking cessation and prevention of tobacco use, as well as referrals to other health professionals for smoking cessation programs. Medication use includes medications that were ordered, supplied, administered, or continued during the visit. Only medications related to tobacco cessation were analyzed. These medications were entered as free text for each visit and were limited to no more than eight prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications. The tobacco cessation medications included nicotine replacement therapy (i.e., nicotine patch, gum, lozenge, nasal spray, and inhaler), bupropion, and varenicline.

To estimate recent smoking cessation success among persons aged ≥18 years, CDC analyzed data from the 2005–2009 NHIS. NHIS is a periodic, nationwide, household survey about the health and health care of a representative sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. The NHIS sample during 2005–2009 included 128,608 adults aged ≥18 years, ranging from 21,781 in 2008 to 31,428 in 2005. Recent smoking cessation success was defined using the Healthy People 2020 definition (objective TU 5.1) (5): former smokers who had ever smoked 100 cigarettes, do not smoke now, and last smoked 6 months to 1 year ago were considered to have had recent smoking cessation success. Former smokers who had ever smoked 100 cigarettes, do not smoke now, and last smoked ≤6 months ago and current smokers who initiated smoking at least 2 years ago were considered to have had unsuccessful recent smoking cessation. Recent smoking cessation success was analyzed by whether the respondent had visited a physician within the last year.

All analyses were conducted using statistical software to account for the complex sample design of both NAMCS and NHIS. Data from NAMCS and NHIS were adjusted for nonresponse and weighted using the 2000 U.S. standard population to provide national estimates of outpatient visits with tobacco screening, tobacco cessation counseling, cessation treatments and successful cessation, respectively; 95% confidence intervals were calculated for both surveys to account for the multistage probability sample design. For NHIS, linear trends were examined using orthogonal polynomial contrasts. Statistical significance of differences between those who saw a physician and those who did not was determined using a t-test, with significance set at p<0.05.

Results

During 2005–2008, adults aged ≥18 years made an estimated annual average of approximately 771 million outpatient visits (an estimated total of 3.08 billion visits during 2005–2008 combined) to office-based physicians, ranging from 720 million in 2006 to 799 million in 2007, of which an average annual estimate of approximately 483 million (62.7%) included tobacco screening, an estimated total of 1.93 billion visits during 2005–2008 combined (66.9% in 2005, 61.6% in 2006, 58.7% in 2007, and 63.6% in 2008) (Table). Of the visits in 2005–2008 that included tobacco use screening, 17.6% (340 million visits) were made by current tobacco users (17.2% in 2005, 18.3% in 2006, 19.6% in 2007, and 15.4% in 2008).

The prevalence of respondents who received tobacco screening varied by race/ethnicity; Hispanic patients were less likely to receive screening for tobacco use (57.8%) during office-based physician visits than were non-Hispanic white patients (64.1%). Screening also varied by insurance status. Patients with private insurance (64.8%), Medicare (62.0%), Medicaid or SCHIP (63.4%), and self-payers (charges paid by the patient or patient's family and not reimbursed by a third party) (63.7%) were more likely to receive tobacco screening than were patients with workers' compensation, classified as no charge or charity, or covered by a source other than private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid/SCHIP, workers' compensation, self-pay, and no charge or charity, or whose insurance status was unknown (50.2%). Patients who visited their primary care physician were more likely to receive tobacco screening (66.6% of visits) than patients who visited a physician who was not their primary care physician (61.6% of visits). Screening also varied by physician specialty. Patients visiting general or family practitioners (66.4%) and obstetricians/gynecologists (69.6%) were more likely to receive screening than patients who visited physicians in other specialties (58.2%), excluding internal medicine, cardiovascular disease, and psychiatry.

Patients aged <65 years, men, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and persons of multiple races were more likely to be current tobacco users than were Hispanics and Asians/Pacific Islanders. Patients who were identified as current tobacco users also varied by type of health insurance, with visits made by those with Medicaid/SCHIP (33.2%) and those who were self-payers (26.6%) more likely to be current tobacco users than those with private insurance (17.1%) or Medicare (12.5%). In addition, patients who were screened for tobacco use by their primary care physician were more likely to be current tobacco users (18.7% of visits) than patients who were screened by a physician who was not (16.2% of visits). Patients who visited certain physician specialists were more likely to be identified as current tobacco users (general or family practice, 21.9%, and psychiatry, 23.4%) than patients who visited other specialists, excluding specialists in internal medicine, cardiovascular diseases, and obstetrics/gynecology (15.5% of visits).

Among the patients who were classified as current tobacco users, 20.9% received tobacco counseling during their physician visit. Visits that included tobacco counseling varied by patient's age, with patients aged 45–64 years receiving a higher percentage of counseling (22.7%) than patients aged 25–44 years (17.9%). Among all outpatient visits for current smokers identified by screening, visits that included tobacco counseling also varied by type of health insurance; patients with private insurance (20.8%), Medicare (22.4%), Medicaid/SCHIP (22.8%), and self-payers (23.5%) were more likely to receive counseling than patients who had workers' compensation, were classified as no charge or charity, were classified under other sources of payment (i.e., other than private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid/SCHIP, workers' compensation, self-pay, and no charge or charity), or whose insurance status was unknown (12.5%). Visits that included tobacco counseling also varied by whether the physician was the patient's primary care physician (26.9% of visits) or was not (15.5% of visits). Likewise, visits that included tobacco counseling varied by physician specialty; visits to internal medicine physicians (32.5%) and cardiovascular disease specialists (35.4%) were more likely to include counseling than visits to general or family practitioners (23.5% of visits) and obstetricians/gynecologists (19.7% of visits). Outpatient visits of ≥20 minutes were more likely to include counseling (23.6%) than those of <20 minutes (18.6%).

Among the patients who were identified as current tobacco users, 7.6% received a prescription or an order for a medication associated with tobacco cessation. An order for a cessation medication varied by health insurance, with patients who had private insurance more likely to receive a prescription or order for cessation medication (9.7%) than patients with Medicare (5.5%). An order for a cessation medication also varied by physician specialty; psychiatrists were more likely to include an order for a cessation medication (17.7%) than other specialists. (Psychiatrists had a higher proportion [95.2%] of orders for bupropion, which can be used both as an antidepressant and as a tobacco cessation medication, than all specialists [57.7%]). Of visits with a medication order, 95.4% of the visits had an order for one cessation medication, and 4.6% had an order for more than one cessation medication. Among patients who were identified as current tobacco users and received a prescription or order for a cessation medication, 97.3% of the medications were for prescription drugs (bupropion, 57.7%; varenicline, 38.7%; and nicotine nasal spray and inhaler, 0.9%).

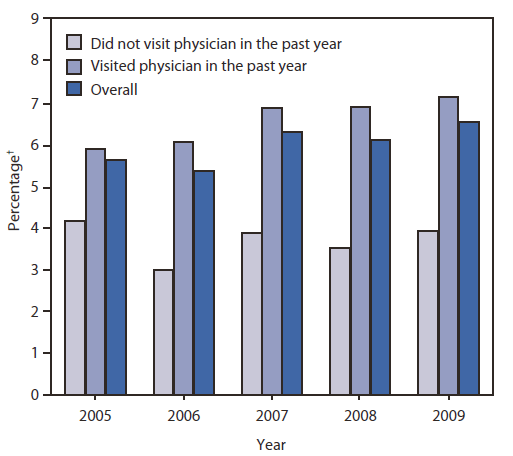

The prevalence of recent smoking cessation success increased significantly from 2005 to 2009 (p<0.05) among adult smokers aged ≥18 years overall and among those who visited a physician in the past year (Figure). No trend in recent smoking cessation success was observed among those who did not visit a physician in the past year. Overall, prevalence of recent smoking cessation success was 6.6% in 2009 (7.2% among those who visited a doctor in the past year and 3.9% among those who did not visit a doctor in the past year [p<0.001 by t-test]).

Discussion

This report indicates that although tobacco use screening occurred during the majority of adult visits to outpatient physician offices during 2005–2008 (62.7%), among patients who were identified as current tobacco users, only 20.9% received tobacco cessation counseling and 7.6% received tobacco cessation medication. The 2008 update to the PHS Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence concluded that to increase tobacco cessation rates, it is essential for clinicians and the health-care delivery system to consistently identify and document tobacco use status and treat every tobacco user with cessation counseling and any of the seven FDA-approved first-line medications (except when medically contraindicated or with specific populations for which evidence of effectiveness is insufficient, such as pregnant women, smokeless tobacco users, light smokers, and adolescents). The Healthy People 2020 objectives for health systems changes related to tobacco use include goals for increasing both tobacco screening and tobacco counseling among tobacco users in office-based ambulatory care settings (objectives TU-9.1 and TU-10.1).

The demographics of patients who were classified as current users of tobacco were similar to those among all U.S. adults who use tobacco (2). The findings in this report indicate that screening for tobacco use was lower among Hispanic patients than among non-Hispanic whites, a finding that is similar to findings from another study using 2001–2005 NAMCS data; in that study, lack of insurance did not explain the ethnic differences (6). Possible explanations for the lower prevalence of tobacco screening among Hispanic patients might include cultural and language differences between the patients and physicians, factors that have been identified as barriers to cancer screening (7). Medical school curricula should include training to address these barriers to preventive services for Hispanic patients as well as other patient populations whose members are underrepresented among physicians (8,9).

Tobacco counseling among adults aged 25–44 years was less prevalent than among older patients. This finding is notable because younger smokers are more likely than older smokers to have tried to quit in the past year and are less likely to succeed in quitting (10). Successful quit attempts begin to occur, on average, at age 40 years, and the percentage of former smokers among those who ever smoked ≥100 cigarettes (an indicator of successful cessation) also increases with age (10). Some physicians might believe that younger patients are not seriously interested in quitting (10). However, tobacco information also should be provided to patients who seem unwilling to quit as a way to encourage them to think about quitting (4). Although tobacco cessation is beneficial at any age, intervening as early as possible is important because quitting at age 50 decreases by half the smoking-related health effects, and quitting at age 30 prevents almost all of the effects to the level of a never smoker (11,12).

During 2005–2008, patients who were current users of tobacco who had an unknown health insurance status or other selected types of health insurance (workers' compensation, no charge or charity, or other sources of payment not covered by private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid/SCHIP, workers' compensation, self-pay, and no charge or charity) were less likely to be screened for tobacco use (all visits) or receive counseling than self-pay patients and those with all other types of insurance (i.e., private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare/SCHIP). The PHS guideline concluded that persons who have insurance that covers treatment for tobacco use are more likely to receive treatment than those who do not (4). Tobacco dependence treatments (both counseling and medication), whether provided as paid or covered benefits by health insurance plans, have been shown to increase the proportion of smokers who use cessation treatment, attempt to quit, and successfully quit (4). Neither private insurers nor state Medicaid programs consistently provide comprehensive coverage of evidence-based tobacco interventions (4). For example, in 2009, although 47 (92%) of 51 Medicaid programs offered coverage for some form of tobacco-dependence treatment to some Medicaid enrollees, only five states offered coverage of all recommended pharmacotherapies and individual and group counseling for all Medicaid enrollees (13). A Healthy People 2020 objective (TU-8) is to increase Medicaid insurance coverage of all evidence-based treatments for nicotine dependency to all 50 states and the District of Columbia (5).

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 as amended by the Healthcare and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (referred to collectively as the Affordable Care Act [ACA]) and other national initiatives will increase tobacco cessation treatment coverage (14). As of October 1, 2010, as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA §4107), state Medicaid programs were required to provide tobacco cessation coverage to pregnant women enrollees with no cost sharing. Effective January 1, 2013, state Medicaid programs that cover prevention services recommended as grade A or B by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force with no cost sharing will receive an enhanced federal matching rate (ACA §4106 ); evidence-based smoking cessation services are grade A recommendations (14,15). Effective January 1, 2014, the Affordable Care Act will also bar state Medicaid programs from excluding FDA-approved cessation medications, including OTC medications, from Medicaid drug coverage (ACA §2502). As of July 2011, Medicaid began allowing states to apply for 50% administrative match funds for telephone quitline services provided to Medicaid enrollees. Also as a part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA §1001), as of January 1, 2014, newly qualified health insurance plans operating in the exchanges* are required to offer their members cessation coverage without cost sharing (16). This requirement also applies to grandfathered plans that were in existence before that date if they undergo substantial changes (17). As of August 25, 2010, Medicare began offering cessation counseling as a covered benefit to all its members; previously, only Medicare enrollees who had already developed tobacco-related disease were eligible for counseling. Effective January 1, 2011, the Affordable Care Act (ACA §4104) also ended Medicare coinsurance requirements for any covered preventive service that is recommended with a grade of A or B by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, including cessation services (14). In addition, as of January 1, 2011, all federal employees began receiving comprehensive cessation coverage through the Office of Personnel Management and the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program. (Additional information on this benefit is available at http://www.opm.gov/quitsmoking.) This new benefit can serve as model for comprehensive tobacco cessation coverage for state and private insurers. Given the decrease in smoking prevalence that occurred after implementation of mandated tobacco cessation coverage for the Massachusetts Medicaid program (18), expanded access to tobacco cessation services and treatments are likely to reduce the prevalence of current smoking among U.S. adults and the related adverse effects.

Other substantial barriers interfere with clinician assessment and treatment of smokers, including lack of knowledge, lack of time, inadequate payment for treatment, and lack of institutional support for routine assessment and treatment of tobacco use (4). The findings in this report indicate that both physician and visit characteristics were related to the likelihood of screening and counseling for tobacco use occurring during a visit. Patients visiting their primary care physician had a higher likelihood of receiving tobacco use screening and cessation counseling than patients who visited a physician who was not their primary care physician, perhaps because the primary care physicians were providing more routine care than specialized care, and tobacco cessation counseling might have been provided as part of a wellness or preventive care visit. In addition, primary care physicians might have had a more established relationship with their patients and felt more comfortable addressing tobacco use than other physicians. General and family practitioners and obstetricians/gynecologists were more likely to screen for tobacco use during patient visits than physicians in other specialties; however, they were less likely to provide tobacco counseling than internal medicine physicians and cardiologists. These differences might be related to the reasons patients visit cardiologists and internal medicine physicians; they might be more willing to make a quit attempt as a result of an acute medical event or a smoking-related health problem (4). More research is needed to identify factors that affect the provision of tobacco screening and counseling in various medical specialties, particularly among obstetricians/gynecologists because of the substantial effects of tobacco on reproductive health, as well as the associated costs (19,20).

The frequency of tobacco counseling was higher among physicians who spent ≥20 minutes with a patient. Lack of time has been noted as a barrier to clinical interventions, and total treatment time is an important determinant of tobacco cessation success. Although clinicians can increase quit rates among patients with even minimal interventions (<3 minutes), the effectiveness of counseling increases with the intensity of the intervention (i.e., session length) up to a total contact time (which might span multiple visits) of 90 minutes (4). Health-care systems can support physician interventions by instituting effective systems-level changes that make screening and brief cessation intervention a standard part of every office visit. According to the Guide to Community Preventive Services (21), provider-reminder systems increase health-care providers' assessment and treatment of tobacco use in a range of clinical settings and populations. Provider reminder systems remind or prompt providers to screen and treat patients for tobacco use and can be implemented as chart stickers, vital sign stamps, medical record flow sheets, check lists, or as part of electronic medical records. The PHS guideline further recommends that health-care providers offer medication and counseling referrals such as quitlines for patients who are willing to make a quit attempt or offer additional treatment to help patients quit (4). Other patient characteristics, such as educational attainment and language preference, which were not included in NAMCS, might play a role in delivery of health-care services such as tobacco screening and counseling that could be examined in future studies.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, tobacco counseling might have included any information on tobacco or exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke as well as referrals to tobacco cessation programs. Because most adult established smokers (>80%) begin smoking before age 18 years (22), the assumption that most information provided to adults focused on cessation is reasonable. However, separately assessing both the provision of actual tobacco cessation counseling (i.e., problem solving and patient skills training) and referrals to smoking cessation programs would have enabled tracking the use of the of 5 A's more effectively (4). The lack of documentation might be a particular problem in the provision of advice to use OTC medications. Among visits by tobacco users during which a cessation medication was provided, the majority were prescription medications (97.3%). In contrast, OTC medications were the most commonly used cessation therapy that was effective among U.S. adults smokers who made a serious attempt to quit in the past year in 2005 (23). This difference might have resulted from a lack of advice to use OTC medications or lack of documentation of this advice. Some medications that were recommended by the physician might not have been documented. Therefore, OTC medications might be underreported. Second, data collection was limited to entry of eight medications. However, this did not seem to be a barrier to listing all the cessation medications a patient was offered among those who were identified as current tobacco users; tobacco users had, on average, 2.5 medications listed during each visit. Third, because bupropion can be prescribed as an antidepressant, whether a prescription for bupropion was for tobacco cessation or a mental illness is unclear. Bupropion accounted for a larger proportion of the cessation medications among psychiatrists (95.2%) than among all physicians (57.7%); therefore, it is more likely these prescriptions were to treat mental illness rather than tobacco use. Fourth, this analysis might be limited because quality and completeness of reporting varied over time, and changes in recommended tobacco cessation medications changed; for example, varenicline was approved first by FDA in May 2006. In addition, the differences from year to year in the quality of reporting and persons who completed the form might have resulted in differences in the percentage of patients screened for tobacco use. For example, using 2001–2004 NAMCS data, a previous study (24) reported that outpatient screening for tobacco use is 68.2%, higher than the 62.7% in this report. These findings might underestimate or overestimate the prevalence of tobacco screening, cessation counseling, and successful quit rates. Additional research is needed to understand differences in reporting over time. Finally, NAMCS data are primarily obtained through self-reporting by physicians and include no record validation.

Conclusion

Tobacco use screening and intervention is one of the most effective clinical preventive services, both in terms of cost and success (4,25), and is an important component of a comprehensive strategy for increasing tobacco use cessation. As part of its National Tobacco Control Program, CDC recommends that states implement policies and other effective community-based strategies that increase tobacco cessation, in addition to working with health-care systems, insurers, and purchasers of health insurance to expand coverage for tobacco cessation and implement health system changes that support these effective clinical interventions (12,21). Other effective community-based interventions for increasing cessation include increasing the unit price of tobacco products, conducting mass media campaigns combined with other community interventions, providing telephone counseling, and implementing smoke-free legislation (12,21). These interventions are critical for decreasing tobacco use among adults because most persons who try to quit typically do not use any effective services (18,26). Therefore, public health programs should implement a comprehensive tobacco cessation strategy by using policy and media interventions to promote cessation among tobacco users while simultaneously providing affordable, available, and effective services (including counseling and medication) to those who want help to quit (12,21,27).

Acknowledgments

This report is based, in part, on contributions by Stephen D. Babb, Office on Smoking and Health, CDC.

References

- CDC. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. MMWR 2008;

57:1226–8. - CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR 2010;59:1135–40.

- CDC. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR 2011;60:1513–19.

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. Available at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/index.html. Accessed March 30, 2012.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco use objectives. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicid=4. Accessed March 30, 2012.

- Sonnenfeld N, Schappert SM, Lin SX. Racial and ethnic differences in delivery of tobacco-cessation services. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:21–8.

- Garbers S, Chiasson MA. Inadequate functional health literacy in Spanish as a barrier to cervical cancer screening among immigrant Latinas in New York City. Prev Chronic Dis 2004;1:A07.

- Manetta A, Stephens F, Rea J, Vega C. Addressing health care needs of the Latino community: One medical school's approach. Acad Med 2007;82:1145–51.

- Monroe AD, Shirazian T. Challenging linguistic barriers to health care: students as medical interpreters. Acad Med 2004;79:118–22.

- Messer K, Trinidad DR, Al-Delaimy WK, Pierce JP. Smoking cessation rates in the United States: a comparison of young adult and older smokers. Am J Pub Health 2008;98:317–22.

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004;328:1519.

- CDC. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2007. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/index.htm. Accessed March 30, 2012.

- CDC. State Medicaid coverage for tobacco-dependence treatments—United States, 2009. MMWR 2010;59:1340–3.

- University of Wisconsin Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention. Summary of selected tobacco, prevention, and public health previsions from H.R. 3590 and H.R. 4872. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention; 2010. Available at http://www.ctri.wisc.edu/Insurers/HeathReformTobaccoSummary.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2012.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women. Rockville, MD: US Preventive Services Task Force; 2009. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstbac2.htm. Accessed March 30, 2012.

- Cassidy A. Health policy brief: preventive services without cost sharing. Health Affairs, December 28, 2010. Available at http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=37. Accessed April 6, 2012.

- Merlis M. Health policy brief: 'grandfathered' health plans. Health Affairs. October 29, 2010. Available at http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=29. Accessed April 6, 2012.

- Land T, Warner D, Paskowsky M, et al. Medicaid coverage for tobacco dependence treatments in Massachusetts and associated decreases in smoking prevalence. PLoS One 2010;5:e9770.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. How smoking causes disease: the biological and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010. Available at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/tobaccosmoke/report/index.html. Accessed March 30, 2012.

- Adams EK, Miller VP, Ernst C, Nishimura BK, Melvin C, Merritt R. Neonatal health care costs related to smoking during pregnancy. Health Econ 2002;11:193–206.

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The guide to community preventive services: tobacco use prevention and control. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/comguide/index.htm. Accessed March 30, 2012.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2009. NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434.

- Curry SJ, Sporer AK, Pugach O, Campbell RT, Emery S. Use of tobacco cessation treatments among young adults smokers: 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1464–69.

- Ferketich AK, Khan Y, Wewers ME. Are physicians asking about tobacco use and assisting with cessation? Results from the 2001–2004 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Prev Med 2006;

43:472–6. - Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med 2006;

31:52–61. - Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med 2008;

34:102–11. - US Department of Health and Human Services. Ending the tobacco epidemic: a tobacco control strategic action plan for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health; 2010. Available at http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/tobacco/tobaccostrategicplan2010.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2012.

FIGURE. Percentage of adult smokers* aged ≥18 years who recently quit smoking, by whether persons visited a physician in the past year — National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005–2009

* Number of adults who ever smoked 100 cigarettes, do not smoke now, and last smoked 6 months to 1 year ago. The denominator included number of adults aged ≥18 years who have ever smoked 100 cigarettes, do not smoke now, and last smoked ≤1 year ago and current smokers who initiated smoking at least 2 years ago.

† Age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. census population.

Alternate Text: This figure is a bar chart that shows the percentage of adult smokers aged ≥18 years who recently quit smoking and whether the persons visited a physician in the past year (National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005-2009). The chart shows that the prevalence of recent smoking cessation success increased significantly from 2005 to 2009 among adult smokers aged ≥18 years overall and among those who visited a physician in the past year. No trend in recent smoking cessation success was observed among those who did not visit a physician in the past year. Overall, the prevalence of recent smoking cessation success was 6.6% in 2009 (7.2% among those who visited a physician in the past year and 3.9% among those who did not visit a physician in the past year.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents.

This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version.

Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr)

and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.

Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371;

telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to

mmwrq@cdc.gov.