Training Epidemiologists in Guinea to Respond to Infectious Disease Outbreaks, from Ebola to COVID-19: A First- Person Account by Dr. Salomon Corvil

April 5, 2022

A Guinea FETP resident briefs health workers about the signs and symptoms of Ebola so they can detect suspected cases in 2021. Photo: Salomon Corvil/CDC

In November 2016, Salomon Corvil, MD, MPH, a graduate of the two-year Haiti Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP), moved from his native Haiti to become the field coordinator for the FETP-Frontline and FETP-Intermediate in Guinea.

The FETP is a service-based program that trains public health workers in the principles and practices of field epidemiology. FETP’s objective is to strengthen public health systems around the world by training epidemiologists, or “disease detectives,” in disease surveillance, laboratory management, emergency response, and outbreak investigations. To strengthen surveillance and epidemiology capacity at all levels of the public health system (from local to regional to national), the FETP model comprises three tiers: Frontline, Intermediate, and Advanced. During Dr. Salomon Corvil’s time in Guinea, he has made a significant impact by strengthening the FETP, as he describes below. Here, Dr. Corvil reflects on his involvement with FETP over the past decade, both in Guinea and his native Haiti.

An FETP resident looking for Ebola contacts in the community during the 2021 Ebola outbreak in Guinea. Photo: Salomon Corvil/CDC

During the 2014‒2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic, the shortage of experienced field epidemiologists in Guinea, and in the region in general, became quite evident. To help remedy this situation, CDC and its partners worked with the Guinean Ministry of Health to establish an FETP in the country. As a result, in 2016, I became the first resident advisor (RA) for both FETP-Frontline and -Intermediate in Guinea through a contract managed by the African Field Epidemiology Network. My main work is to train surveillance officers in basic epidemiology.

I believe I was chosen because of my decade’s worth of experience with FETP. I became involved with the program in 2011, when I enrolled in the first Haiti FETP-Basic (now called Frontline) group. I eventually graduated from FETP-Intermediate and -Advanced as well. The Haiti and Guinea FETPs have a commonality: both were launched after an urgent public health crisis of unprecedented magnitude. In Haiti, the FETP was launched after the January 12, 2010, magnitude 7 earthquake. So, I was already familiar with the challenges of starting a program under difficult conditions. In addition, I am a French speaker, so my background and experience were an ideal fit for Guinea.

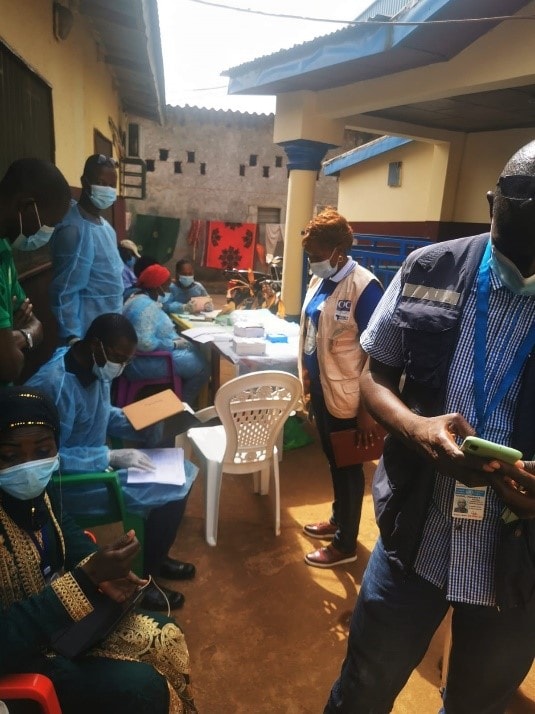

FETP residents conduct COVID-19 vaccination activities in Conakry, the capital of Guinea in 2021. Photo: Salomon Corvil/CDC

On average, I train between 42 and 54 people (combined) per year who are divided into FETP-Frontline and FETP-Intermediate. Participants are healthcare professionals that include nurses, physicians, and veterinarians. Because Guinea doesn’t have its own FETP-Advanced, those who want to continue to the advanced level join the program in the African country of Burkina Faso. It is a regional program that trains residents from several Francophone countries in West Africa. So far, three Frontline graduates have enrolled in the advanced Burkina Faso FETP and received a master in public health degree from the Université Joseph Ki-Zerbo, in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Five more Frontline graduates are currently enrolled in that same program.

When I was asked to become the RA in Guinea, I was thrilled and eager to be involved in the program. I knew that my experience in Haiti would be very helpful. Since the beginning of the program, the capacity to conduct disease outbreak investigations and analysis has greatly improved. The country is able to better respond to outbreaks and the surveillance system has been strengthened. This is evident when you compare the 2014‒2016 Ebola response with the 2021 Ebola response.

During the first outbreak, it took four months to identify the first person who caught the disease, but during the second outbreak it took only 15 days. The first epidemic spread to 31 districts in Guinea and neighboring countries. The 2021 outbreak was contained in one district called N’Zérékoré, in the Forest Region of Guinea. The first outbreak lasted for two and a half years and ended with more than 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths in West Africa. The second outbreak lasted four months with 11 survivors and 12 deaths. Finally, during the 2014‒2016 outbreak, public health officials struggled with making decisions because they were unfamiliar with how to handle an epidemic, but in 2021 decisions could be made swiftly because Guinea had experienced disease detectives. The outbreak was declared officially over on June 19, 2021.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) is now firmly in charge of outbreak responses. In the past, partners led data management and vaccination efforts. Previously, there were few investigation reports, and they were of poor quality. Now, I’ Nationale de Sécurité (Guinea’s National Agency for Health Security [ANSS]) has publicly recognized FETP for the quality of the investigation reports.

Similarly, the quality of the surveillance system has greatly improved. For example, in 2017, an FETP-Frontline trainee conducted a data quality audit and found that one facility had registered more than 100 confirmed measles cases but never reported this in the surveillance system. We were able to integrate this facility into the surveillance system and conduct a mass vaccination campaign to stop the outbreak. In addition, the work of the graduates of the first two Frontline cohorts led to more than 200 facilities being integrated into the surveillance system, which led to 98% of facilities reporting on their surveillance activities regularly, compared with only 69% responding before the integration.

Guinea FETP residents are leading discussions with community members on the COVID-19 pandemic in the sub-district of Youkounkoun in 2021. Photo: Salomon Corvil/CDC

In addition to the 2021 Ebola outbreak, Guinea also had to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. I’m working on the COVID-19 response now by helping the MOH with the preparedness and response plan. I provide technical support for the COVID-19 surveillance guidelines as well as help with the daily Situation Response Reports and some data analysis to guide the response.

It is very gratifying for me to witness the direct impact the FETP has had in Guinea from day one and to know that those who are responsible for the surveillance of infectious diseases have the knowledge they need to make the right public health decisions based on science and facts. The capacity to handle a public health crisis of any magnitude is important now, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.