Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis

Rickettsial Disease Diagnostic Testing and Interpretation for Healthcare Providers

This video provides information on rickettsial disease diagnostic methods for healthcare providers, including what tests are available and when it is most appropriate to collect samples. This video focuses on the use of polymerase chain reaction (or PCR) tests, and the indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay for rickettsial disease diagnosis.

Clinical Diagnosis

- Early recognition and treatment is key.

- Maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for anaplasmosis or other tickborne diseases in cases of non-specific febrile illness of unknown origin, particularly during spring and summer months when ticks are most active. Early recognition and presumptive treatment is important to prevent severe illness.

- Because anaplasmosis can be difficult to diagnose, particularly in the early stages of illness, patients should treated presumptively based on clinical suspicion.

- Always take a thorough patient history, including:

- Recent tick bite. NOTE: Tick bites are often painless. Many people do not remember being bitten. Do not rule out a tickborne infection if your patient does not remember a tick bite.

- Exposure to areas where ticks are commonly found, including wooded areas or brushy areas with high grasses and leaf litter.

- Travel history (domestic and international) to areas where anaplasmosis is endemic.

- Laboratory confirmation is helpful for disease surveillance and understanding burden of anaplasmosis infection in the United States.

The diagnosis of anaplasmosis often is made based on clinical signs and symptoms, and can later be confirmed using specialized confirmatory laboratory tests. Treatment should not be delayed pending the receipt of laboratory test results, or withheld on the basis of an initial negative laboratory result.

Laboratory Diagnosis

- Diagnostic test should be run on those with illness clinically compatible with anaplasmosis. However, treatment should not be delayed on the basis of diagnostic testing.

- The optimal diagnostic test may depend on the timing relative to symptom onset and the type of specimen(s) available for testing.

- Testing for anaplasmosis should be considered for any person with a compatible illness and known risk factors, such as:

- Living in or having traveled to an area with anaplasmosis

- Illness occurring during times of year with high tick activity (spring, summer, or fall)

- Those who remember a tick bite

- Anaplasmosis is a nationally notifiable condition. Correct testing and reporting of anaplasmosis is important to improve our understanding of how common this disease is, where it occurs, and how disease trends change over time.

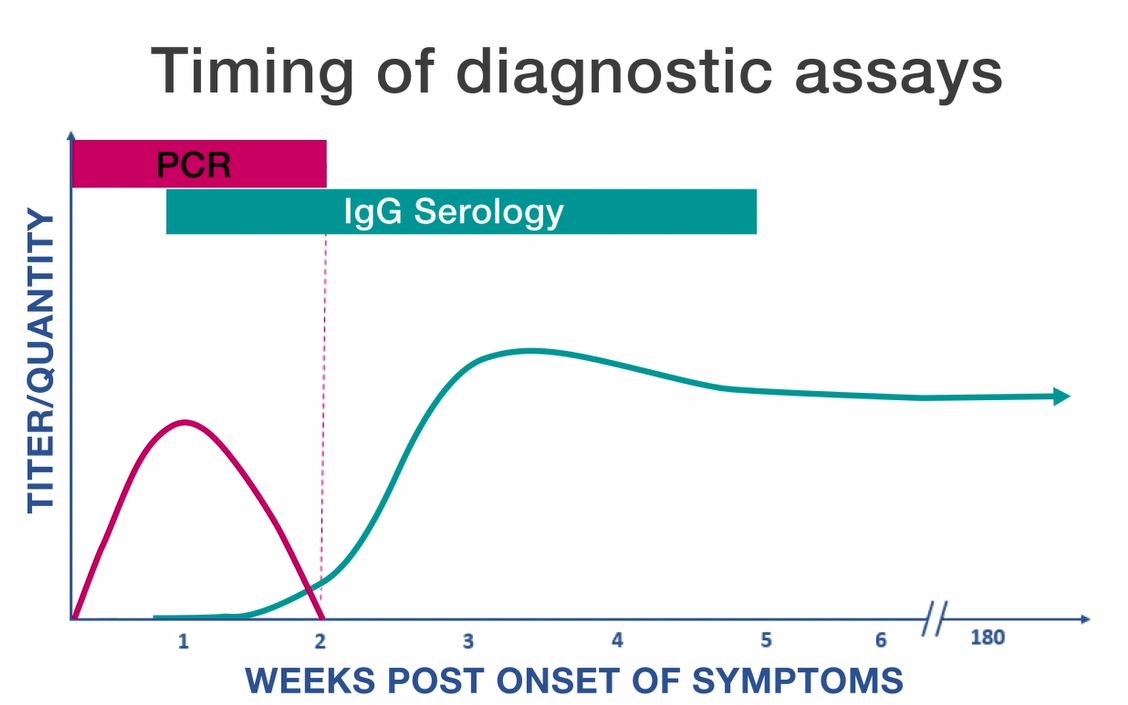

PCR

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification is performed on DNA extracted from whole blood specimens.

- This method is most sensitive in the first week of illness, and decreases in sensitivity following the administration of appropriate antibiotics (within 24–48 hours).

- Although a positive PCR result is helpful, a negative result does not rule out the diagnosis, and treatment should not be withheld due to a negative result.

- PCR might also be used to amplify DNA in solid tissue and bone marrow specimens.

Serology

- The standard serologic test for diagnosis of anaplasmosis is the indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay for immunoglobulin G (IgG) using A. phagocytophilum antigen.

- IgG IFA assays should be performed on paired acute and convalescent serum samples collected 2–4 weeks apart to demonstrate evidence of a fourfold seroconversion.

- Antibody titers are frequently negative in the first week of illness. Anaplasmosis cannot be confirmed using single acute antibody results.

- Immunoglobulin M (IgM) IFA assays may also be offered by reference laboratories, however are not necessarily indicators of acute infection and might be less specific than IgG antibodies.

- Antibodies, particularly IgM antibodies, might remain elevated in patients for whom no other supportive evidence of a recent rickettsiosis infection exists. For these reasons, IgM antibody titers alone should not be used for laboratory diagnosis.

Photo/Bobbi S. Pritt, Mayo Clinic

Persistent Antibodies

- Antibodies to A. phagocytophilum might remain elevated for many months after the disease has resolved.

- In certain people, high titers of antibodies against A. phagocytophilum have been observed up to four years after the acute illness.

- Between 5–10% of healthy people in some areas might have elevated antibody titers due to past exposure to A. phagocytophilum or similar organisms.

- Comparison of paired, and appropriately timed, serologic assays provides the best evidence of recent infection.

- Single or inappropriately timed serologic tests, in relation to clinical illness, can lead to misinterpretation of results.

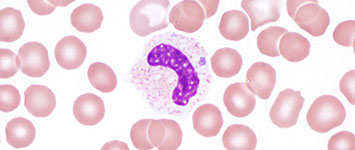

Blood-smear Microscopy

- During the first week of illness a microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear might reveal morulae (microcolonies of anaplasmae) in the cytoplasm of granulocytes and is highly suggestive of a diagnosis.

- However, blood smear examination is relatively insensitive and should not be relied upon solely to diagnose anaplasmosis.

- The observance of morulae in a particular cell type cannot conclusively differentiate between Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species.

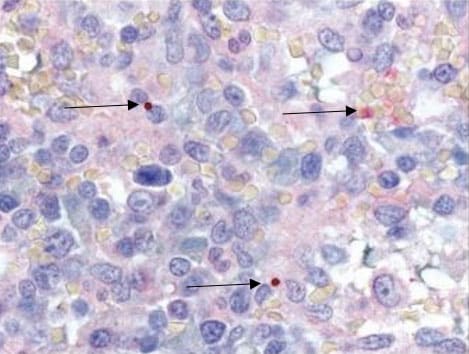

Photo/CDC

IHC and Culture

- Culture isolation and immunohistochemical (IHC) assays of A. phagocytophilum are only available at specialized laboratories; routine hospital blood cultures cannot detect the organism.

- PCR, culture, and IHC assays can also be applied to autopsy tissue specimens.

- If a bone marrow biopsy is performed as part of the investigation of cytopenias, immunostaining of the bone marrow biopsy specimen can diagnose A. phagocytophilum infection.

For more in-depth information about diagnostic testing, see: Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis — United States: A Practical Guide for Health Care and Public Health Professionals (2016) pdf icon[PDF – 48 pages]