Stories from the Field

Partnering for Vaccine Equity

Photos courtesy of El Buen Samaritano

Our partner network works in communities across the U.S. to reduce disparities in immunization, increasing vaccine confidence and uptake. Learn about successes, challenges, and lessons learned from partners’ COVID-19 vaccine work.

For additional success stories from partners funded by the Partnering for Vaccine Equity program, check out the Stories section on the Vaccine Resource Hub.

The COVID-19 Pandemic is revealing many heroes in public health dedicated to keeping Americans safe from disease and saving lives. The Southern Nevada Health District’s (SNHD) Office of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion is a CDC partner doing heroic work when it comes to reducing disparities in adult immunization. SNHD is located in Las Vegas, Nevada and serves 2.3 million people, which is over 75% of the state’s population. In April 2021, SNHD began a COVID-19/Flu project with partner organizations, funded via the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) initiative. The goal is to increase vaccine equity by reaching project priority populations:

- African American adults (13.1% of the population)

- Hispanic adults (31.6% of the population)

Project activities are comprehensive and include an assessment of needs, equipping influential messengers, engaging the community, and distributing vaccines.

Needs Assessment

Getting started requires a true evaluation of needs. To do that, SNHD worked with a firm out of the University of Nevada Las Vegas – The Nevada Institute for Children’s Research (NICRP). Maria Azzarelli, Manager of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion for SNHD said “lucky for us we’ve worked with NICRP for over 10 years conducting needs assessments,” adding “we were able to jump into this project and started learning about what the community was thinking – it was a very exciting and dynamic time, and there was a lot to learn.”

NICRP worked on a map that overlayed a social vulnerability index with rates of completed vaccines in Clark County, where Las Vegas is located. This helped to confirm and identify the zip codes and populations with the lowest vaccination rates. NICRP staff used the map to determine priority locations to conduct a COVID-19 and Flu Vaccination Survey in September 2021. Survey responses were collected from priority populations (98 African American and 87 Hispanic survey respondents). Overall, low levels of vaccine hesitancy were found, but of those who were vaccine hesitant, the most common reasons included the COVID-19 vaccine was too new, there was not enough safety information, and concern over side effects. Respondents largely viewed flu vaccine as unimportant.

NICRP then put together a focus group with young African American/Non-Hispanic Black adults (ages 18 to 35) because this group represented those most at risk of being newly infected with COVID-19 at that time. This focus group built upon the findings of the COVID-19 and Flu Vaccination Survey to better understand disparities in vaccine uptake. Here are some key findings:

COVID-19

Among those who accepted COVID-19 vaccines, focus group participants shared the following reasons:

- Protecting the health of themselves and others

- Having been directly impacted by COVID-19

- Resuming life and getting back to normal

- Viewing access to vaccines as a privilege

- Being able to visit family members who are vulnerable to contracting COVID-19

Among those who delayed obtaining COVID-19 vaccines, focus group participants shared the following reasons:

- Did not view it as a high priority

- Planned to get vaccinated, just not right now

- Did not view the vaccine as a solution to the problems revealed by the pandemic

- Had low access to health care

Among those who refused the COVID-19 vaccine, focus group participants shared the following reasons:

- Afraid of long-term vaccine side effects

- Had preexisting health conditions

- Followed the advice of a health care provider*

Flu

Many focus group participants reported accepting the flu vaccine simply because it was offered to them when obtaining COVID-19 vaccines. Other motivators for accepting the vaccine included:

- Protecting their health

- Following work requirements

- Routine

Participants shared several reasons for flu vaccine hesitancy, which included:

- Fear of side effects

- Past experiences with side effects

- Not viewing flu vaccines as routine or normal in their family

- Not viewing flu vaccines as necessary

- Never occurred to them to get a flu vaccine

SNHD gathered feedback from community partners as well. Azzarelli emphasized, “we couldn’t do this without relationships we had prior to the pandemic – relationships with community partners, businesses, and faith community,” adding, “we knew the value of community health workers like promotores that speak the language of our community, answer questions, and provide feedback to us – it’s been a wonderful relationship.”

Equipping Influential Messengers

SNHD used the information gathered in the needs assessment to train 230 community-level spokespersons to combat misinformation and support vaccine uptake among Clark County residents. These spokespersons included community health workers, faith and cultural leaders, barbers, beauticians, business owners, radio DJs, and other public figures. Azzarelli said “there was a huge void in our community regarding flu vaccination and the importance of it. Our needs assessments were showing many people felt that flu vaccination was unimportant, they were afraid of side effects. We focused on dispelling myths and explaining the importance of flu vaccination.” To do that, the influential messengers are provided with information to combat misinformation – they are provided with CDC resources and training. “It’s constant education making sure our community partners are equipped with the latest materials and science,” Azzarelli said.

Engaging the Community

The COVID-19/Flu project continued with the implementation of 11 media campaigns between April 2021 and September 2022 that generated over 28 million TV, online, and radio ad impressions. SNHD also worked with communities and stakeholders to strengthen 131 provider partnerships and participated in 58 community events with more than 19,000 attendees to promote and increase access to COVID-19 and flu vaccination. Azzarelli said “we put a significant portion of our budget into media understanding that you have to be out there utilizing commercial strategies – we’ve done that in English and Spanish and utilized social media platforms as well,” adding that “we’ve also taken an unconventional approach – using barbers, DJs, and promotores.” Messages were posted on Facebook and Instagram. Radio DJs created their own posts using SNHD talking points, but in their styles. Azzarelli points out “we wanted individuals who really believe in this (vaccination), and then didn’t go and promote something contradictory to the pro-vaccine message on their social media platforms.”

Distributing Vaccines

There’s a lot of work that goes into organizing pop-up vaccination clinics. SNHD works with vaccination partner Immunize Nevada to provide these services. These clinics were in a variety of locations focused on the African American and Hispanic communities. “We weren’t trying to reach thousands of people in one location – we focused on hard-to-reach people.” Azzarelli said that brings challenges. “[Communities] that are most in need often have multiple barriers to accessing resources. Vaccination partners dealt with hecklers – their job is hard enough.”

The pop-up vaccination clinics are placed with an emphasis on access. These clinics are in places that people can walk to such as community centers that are close to public transportation. “Most feedback is positive – people express their gratitude for pop-up clinics in their neighborhoods,” Azzarelli said.

The work is ongoing and yielding positive results. Between April 2021 and September 2022, 147 mobile pop-up clinics were facilitated serving zip codes with low vaccine coverage rates. 4,253 COVID-19 vaccines and 1,009 flu vaccines were administered with 95% of vaccinated individuals identifying as African American or Hispanic. Azzarelli sums up the point of these efforts: “If we weren’t available in their neighborhoods, many people would not get vaccinated.”

Looking Ahead

SNHD remains committed to achieving vaccine equity. Azzarelli believes one of the key lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic is keeping relationships strong in the community so that when health emergencies happen in the future, a strong trust has been built. “Developing relationships in areas of highest need is so important in advance of anything happening. We need to work on those relationships to tackle many other public health issues, and not wait for the next pandemic to come.” She also believes COVID-19 brought inequity to light: “we need to utilize the momentum to build upon the gains in vaccine equity during this pandemic.”

*Note: With the exception of very rare cases where an individual has a contraindication for COVID-19 vaccination (such as a severe allergy to one of the vaccine ingredients), CDC recommends COVID-19 vaccination for everyone ages 6 months and older. For more information, see: Clinical Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination | CDC

Locally driven partnerships and community-designed solutions are essential for addressing the root causes of health disparities and ensuring health equity. However, it takes time to build trust within many communities that are underserved and experience distrust of governmental institutions. The approach of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ (ASTHO) is to develop community-driven solutions designed to provide leadership opportunities, technical support, and advocacy for community action programs. This type of public health/community action partnership is a model that can be applied nationwide. The regional presence and capacity of Community Action Program agencies (CAPs) to reach deeply into communities are an often-untapped resource for public health. They enable public health to work more directly with community members and community organizations on a more local level.

CAPs are non-governmental community-based agencies working with the governmental health and human services system. Authorized under the 1964 Economic Opportunities Act, state health and human services departments contract with CAPs using the federal Community Services Block Grant (CSBG). CAPs have a long history of assisting people experiencing economic insecurity and housing instability, as well as providing support for people living with disabilities. They serve people in every age group – from infants in Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program clinics to young children in Head Start to seniors receiving heating assistance and home care. CAPs also have the infrastructure in place to handle administrative functions on behalf of smaller nonprofits, such as procurement, payroll, and fiscal management.

With funding from the CDC, ASTHO is working with the National Community Action Partnership to engage five CAPs and their respective networks of local community action teams in five geographic areas:

- Pickens Community Action – Pickens County, AL

- Enrichment Services Program, Inc. – Russell County, AL and Troup and Stewart Counties, GA

- Community Action Partnership of Kern – Kern County, CA

- Community Action Program for Central Arkansas—White County, AR

- Palmetto Community Action Partnership – Berkeley County, SC

ASTHO CEO Michael Fraser says, “the result of this work will be instrumental in informing future vaccination efforts in our member states and territories.”

These CAPs take evidence-based strategies to increase vaccine equity and tailor them to their own communities. For example, in Berkeley County, South Carolina, Palmetto Community Action Partnership works with the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (SCDHEC) and Fetter Health Care Network (Fetter) to promote vaccination during patient visits. SCDHEC provides nursing outreach teams who administer on-site vaccinations at events throughout Berkeley County. Fetter administers flu vaccines at its income-based health clinic in rural Berkeley County, and patients are encouraged to receive them through ASTHO’s Vaccine Equity Project. Palmetto Community Action Partnership held COVID-19 vaccination events during the summer with a focus on fun. A “Sports Extravaganza” vaccination event was held at a recreation facility in Moncks Corner, South Carolina featuring retired NFL players and members of the Charleston Southern University football team. A “Community Day” in partnership with Jean Angels at Berkeley High School featured food trucks, jump castles, and a partner resource fair.

The CAPs mentioned above are addressing vaccine hesitancy by working with local leaders to serve as trusted messengers. These include faith-based leaders, local providers such as physicians but also community health workers and emergency medical technicians (EMTs). They are also engaging their local medical and nursing schools to build up the next generation of providers as vaccine champions.

These CAPs are seeking to dispel distrust and misinformation by sharing credible information through as many means as possible: through social media, traditional media, and most importantly through one-one-conversations at local health fairs and vaccine clinics. Their trusted messengers share stories of how and why they were vaccinated. In addition, the CAPs meet the holistic needs of their community members by addressing the social determinants of health: they provide food, housing, and utilities assistance, job training programs, and childcare for low-income families. With their reputation as trusted resources, and their extensive network of local partnerships, the CAPs reach those harder-to-reach segments in their communities.

ASTHO’s new partnership with these CAPs serves as a promising example of public health/community action collaboration to improve the health of individuals in the community and increase vaccine equity in areas that face disparities. ASTHO believes such partnerships can be replicated to address other types of health equity issues such as chronic disease prevention or improving community resiliency.

Over 1 million people have died from COVID-19 in the United States (U.S) with higher rates among racial and ethnic minority groups. There are over 60 million Hispanic people in the U.S. accounting for nearly 20% of the country’s population. Over the course of the pandemic, the Hispanic population experienced 1-and-a-half times more cases of COVID-19, over 2 times more hospitalizations, and nearly 2 times more deaths in comparison with White, non-Hispanic groups. See more here.

Communities RISE (Reach, Immunizations, System Change for Equity) Together is an alliance of partners connected to over 2,400 organizations across the nation working to address barriers to COVID-19 vaccination. RISE connects health departments with community messengers and builds communications campaigns to address misinformation and disinformation regarding vaccines. Somava Saha is Executive Co-Lead with RISE, and she says you have to trust the people who are involved in their respective communities. “The people closest to the ground know what is going on, and you trust them to tell you what people are feeling. When you allow those you trust to lead the strategy you get to different results.” Saha adds, “RISE was created in the context of the pandemic to assure that our communities of color and communities experiencing inequalities don’t get harmed but are able to lead the response in their neighborhoods. We brought together 10 national partners to work with Black, Indigenous, Hispanic, and other communities to create that response.”

Latino Health Access (LHA) is one of those partners. LHA continues to work with the medical community in south metro Los Angeles, CA to bring COVID-19 testing, education, and COVID-19 vaccine to some of the hardest hit communities in Santa Ana, Anaheim, and San Juan Capistrano. LHA is a non-profit organization serving the Orange County community for nearly 30 years through services ranging from diabetes self-management classes, emotional wellness assistance, and advocating for policy change to improve people’s lives.

The vaccination gap within Hispanic communities is compounded by a variety of challenges (or barriers) including language barriers, no internet access, difficulty getting access to vaccines, transportation issues, and mistrust in the health care system. LHA Chronic Illness Program Coordinator Guillermo Alvarez emphasizes, “once you break that trust, it’s very hard to get back.” He adds that Hispanics in his community needed a way to talk about their concerns or fears, and community leaders and trusted public figures could help with that. This is where promotores come into play. Promotores are Hispanic community members who receive specialized training to provide basic health education in the community. Promotores are stationed throughout communities in common places like churches, grocery stores, and schools. Promotores are able to expand their reach by engaging community members outside of typical health systems, and by addressing concerns about getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

COVID-19 Vaccine Concerns Expressed by Community Members

- I do not want the virus injected in me

- I have heard people have died after receiving the vaccine – what will happen to me?

- Will I get COVID after getting vaccinated? Will I get sick?

- I have a medical condition – is it safe for me to get the vaccine?

- Reading or hearing information that creates fear of the vaccine.

There were a lot of hurdles to overcome in getting the Hispanic community vaccinated – especially the way vaccines were distributed. Alvarez says, “the big vaccine clinics that were put up by our county were far away from the most vulnerable communities that needed access. They were also in languages our communities couldn’t understand. A lot of it was in technological terms and a lot of our community doesn’t even have email so being able to register for a vaccine was a barrier.” Alvarez went on to say, “in the Latino community a lot of the parents depend on their kids to make doctor’s appointments, and this was highlighted during COVID vaccine distribution. If the parents didn’t get help, what were they to do at that point?”

There were also concerns that Orange County did not properly include underserved communities in its vaccination distribution plans which focused on COVID-19 vaccine POD (Point of Dispensing) sites at Disneyland and the Anaheim Convention Center. Maria Cervantes is the Director of Partnerships and Strategic Communications with LHA. She points out “most of the POD sites were drive through and many in our community don’t have cars, so they couldn’t just walk up to a POD and get taken care of.” The original idea behind the POD sites was to increase the number of vaccines that were distributed. Cervantes wonders whether proper consideration was given to the difficulty low-income and underserved community members would experience in trying to get to the POD sites.

LHA found ways to address these hurdles. They partnered with local clinics to bring COVID-19 vaccines to communities. Alvarez says, “We did it at parks, we did it at apartment complexes, we did vaccination clinics in parking lots, and at churches. We would take a week or two to advertise the event and then collaborate with different partners such as grocery stores and school districts just to get word of mouth.” They also had clinics on weekends and holidays. Alvarez said they started the clinics later in the day, and kept them open into the early evening, so more people could come. They utilized holidays, such as MLK day and President’s Day, because that was when community members were off and could get vaccinated. Cervantes was especially pleased with one particular effort to get people vaccinated. “We created a vaccination float that we took to these very needy communities. We let people know we were coming with a megaphone and played music. We brought information in their respective language and an environment of happiness. We brought the clinics to them- it helped make people more comfortable.”

LHA also worked to provide a van to shuttle older adults to and from clinics. Only 2-3 people were taken at a time so they could socially distance. There were also times when someone driving to work would drop off a family member to receive a vaccine. LHA would pay a ride sharing service to take that person home. Alvarez says many in these communities live paycheck to paycheck so missing any work to get vaccinated was definitely a reason people didn’t get vaccinated. “In Santa Ana County, where we are based, it’s very common to have 2, 3, or 4 families living together to share the rent because it is so high. Many of these people prioritize work over getting a vaccine because they can’t afford to miss a paycheck for fear of getting evicted.”

A lot of LHA services are created from a need in a community. Alvarez says listening to the promotores is important. “When our promotores say there is a service that is needed in the community, that’s when LHA does its best to find a way to solve that need or gets grants to help solve it. We did so much for community members other than just setting up appointments. We set up a call center, we set up a contact tracing center. Because our community members had technological issues, we had our promotores go to them and let them know if they tested positive and then they made sure they had everything they needed to isolate properly.”

So, what does Alvarez think is his organization’s biggest success during the pandemic? “It is training our promotores to use technology. That was a barrier at first for our participants and internally as well. Some of our promotores didn’t have a lot of formal education. Some didn’t know how to read or write; some didn’t know how to use computers so being trained to use Google voice and Zoom was important. We have a data base system where promotores enter all of their own data so that is a success story.”

He adds, “Hopefully COVID comes and goes but the tools we are giving them will stay with them for any other project they are given in the future – whether it be diabetes, emotional wellness, or civic engagement these are tools they are going to be able to take.”

Alvarez says there were lessons learned as well. “Hopefully this (a pandemic) doesn’t happen again, but if it does, we understand a lot more about how to get the word out. Also, involve the community before developing any plan or solution. They will be able to provide 95-98% of the answers you need and when you involve them you build trust.”

Cervantes adds, “The biggest lesson learned to me is staying true to the mission and bringing health equity to the impacted communities.”

This content was also posted on COVID-19 Vaccine Community Features | CDC.

“Burnout is real.” That is what Julian Graves with CDC partner organization RAO Community Health (RAO) in Charlotte, North Carolina says about the challenges of COVID-19 communication two-and-a-half years into the pandemic. As COVID-19 and Seasonal Flu Coordinator, Graves and his colleagues at RAO wanted to provide a unique forum for young Black men to speak about the pandemic and the issues they face. Ashley Carmenia is RAO’s Health Equity Director, and she tells her team to “get creative – don’t be afraid to think outside of the box because conventionalism isn’t going to get you anywhere.”

So, what did the team come up with? A barbershop talk. Barbershops hold a special place in the Black community. They are a long-standing community hub seen as a safe place for raw, honest conversation – including health discussions – while getting a haircut.

The barbershop talk provided a platform for four young influential Black men living and working in the Charlotte area:

- Demetrius Ross, Barber and Manager at The Duck’s Feet Preen and Co.

- Jamall Kinard, Executive Director of the Lakewood Neighborhood Alliance

- Johnathan Hill, Vice President of Public Relations and Communications with 100 Black Men of Charlotte

- “No Limit Larry,” Morning Radio Host, Power 98 FM

Graves moderated the barbershop talk, which lasted 44 minutes. During that time the men discussed COVID-19 and its effects on the Black community.

There were some definite takeaways from the conversation. The men didn’t know what to think about the pandemic at first, but soon they understood the severity of COVID-19 when family members got sick. Ross talked about his uncle dying of the disease. Hill described his own experience with COVID-19 and being scared while battling a fever for several days. The speakers also talked about the importance of going to the doctor for regular checkups. No Limit Larry, the radio host, says “when Black fathers don’t go to the doctor, it affects their kids,” adding “what they see is what they’ll be.” You can experience this compelling conversation in a video of the barbershop talk here.

The barbershop chat provided a forum for candid conversation about issues in health that affect the Black community. Many Black men do not trust government health messages. Hearing from trusted messengers in their communities can help persuade them to get vaccinated and to see a doctor for routine checkups. Carmenia says it is important to work with trusted messengers because “doctors and nurses don’t have 2-to-3 hours to sit with people and talk to them about their concerns, so it’s important to get out in the community and listen.” Carmenia also emphasizes the vital role of trust. “We found that working with community-based partners and organizations that have already been on the ground facilitates trust in the community better,” she says.

The barbershop talk video was released in mid-May and was distributed on RAO’s website, Vimeo channel, Twitter, and Instagram accounts. The video was also shared on the Instagram profiles of the four men interviewed. As of mid-September, the video had earned more than 63,0000 ThruPlays (the number of times the video was played for at least 15 seconds) on Facebook. There were also 840 plays on Instagram Reels. That success led Carmenia to host a conversation with four influential black women in a Charlotte area gym which will be available on RAO’s website later this year.

RAO strives to tie in much of its CDC-funded Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) work into efforts to increase vaccine confidence, as well as educating community members on good habits to improve their overall health. These efforts include providing annual flu vaccines and helping people get primary care providers. Carmenia knows all too well the health dominoes that fall – “African-American men experience higher rates of heart disease, obesity, and diabetes. These comorbidities make this population more likely to have serious COVID-19 symptoms.” RAO hopes the barbershop talk and future communication campaigns can help address barriers to vaccine administration and enable a more holistic and equitable approach to health care.

Vaccination rates for Hispanics are often lower than rates for other racial and ethnic groups. Efforts to encourage COVID-19 vaccination among Hispanic populations in the United States often face substantial barriers. These barriers include access to information about the vaccines, language accessibility, and transportation challenges. Additionally, many individuals within these groups lack health insurance and state identification, which pharmacies and other clinics often request. The Hispanic Center of Western Michigan (The Hispanic Center) is a nonprofit organization working to remove barriers to getting vaccinated. The region they serve includes Grand Rapids, the largest city in western Michigan and the second-largest city in the state. Hispanic people make up nearly 17% of the population of Grand Rapids, which is comparable to the overall population of Hispanic people in the U.S. (18%).

The Hispanic Center collaborated with Michigan’s Community Foundation of the Holland/Zeeland Area, the University of Michigan Health-West, and the Kent County Health Department to provide COVID-19 vaccines to Hispanic residents from November 2021 through January 2022 via weekly mobile vaccine clinics. In total, 165 doses were administered in November and increased to more than 330 doses per month in December and January. To ensure success, these organizations had to be intentional about addressing the following barriers to vaccination.

Provided equitable access to information. The Hispanic Center worked to build community trust by sharing flyers conveying COVID-19 information in grocery stores and homes, and by having one-on-one conversations with many of the people receiving the information. Center staff also provided information at school meetings, and they regularly shared information and videos on social media.

Developed accessible and inclusive educational materials. The Hispanic Center assists multiple organizations with translating and interpreting COVID-19-related materials, including information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and local health departments. Elizabeth Hickel, Communications and Development Coordinator with the center, says, “Translations are available here at the Hispanic Center for over 80 languages, and we have a team of over 50 interpreters.” Interpreters assisted nurses, and Spanish-speaking volunteers helped people with vaccination registration and in understanding the overall process. In addition, the center worked with bilingual doctors and community members to create educational videos in Spanish about COVID-19 vaccination. This content was shared by local and trusted Spanish-speaking media outlets that included radio stations, newspapers, and social media.

Addressed transportation challenges. The Hispanic Center provided bus passes for people coming to the mobile vaccination site in the center’s parking lot. There is a bus stop just a block away from the center. The center also contracted a bus for two months to pick people up from their homes and bring them to the site. This improved accessibility for people with transportation barriers and those who don’t have access to a mobile phone to request Uber, which was providing free rides to get vaccinated.

Eliminated the requirement of a state identification and/or proof of health insurance at vaccine clinics. This was extremely important because Hispanic people are the largest population segment without health insurance coverage in the nation. Hispanic people with undocumented immigration status may fear their information will be recorded and shared with immigration authorities. Hickel adds, “Questioning people about their health insurance makes them more hesitant to move forward with receiving the vaccine. A large portion of our community members do not have health insurance, do not have a primary care physician, and do not receive routine check-ups and vaccinations due to the costs associated with each visit. By providing solely vaccines at the Hispanic Center, and removing those questions, we were able to give access to this service to the community.”

This collaboration was successful because governmental institutions and healthcare providers partnered with community-based organizations that have the trust and cultural sensitivity to affect real change among vaccine-hesitant populations in the communities they serve. The center’s comprehensive efforts to vaccinate people against COVID-19 remain strong. Learn more.

In the spring of 2021, when recommendations for COVID-19 vaccination were expanded beyond higher risk populations, many eligible adults in Ohio tried to get their COVID-19 vaccine as soon as they were available to them. However, many others facing language barriers and other challenges were not getting vaccinated as quickly.

That’s when organizations like Asian Services in Action (ASIA) stepped in. ASIA is a health and human services agency serving the Asian American/Pacific Islander community of northeast Ohio. ASIA’s International Community Health Center partnered with the Cleveland Department of Public Health, Cleveland Department of Aging, and Cove City Church to host a pop-up vaccination site in “AsiaTown,” an area of low English-speaking proficiency just a few blocks east of downtown Cleveland.

How did ASIA get the word out? ASIA Chief Executive Officer Elaine Tso said that Ohio’s state government had recently hosted a local mass vaccination site (MVS). She said, “ASIA team members heard from members of the community over WeChat (a Chinese instant messaging and social media app) that language access was a barrier at the MVS. As soon as the location, date, and time of our event were confirmed, we broadcasted it over WeChat for community members to sign up, and they did.” Flyers were also posted to inform the public in Chinese, Nepali, Ka’Ren, Burmese, and Swahili.

The first of two ASIA pop-up vaccination events took place on Sunday, April 18, 2021, when more than 200 people received the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine at Cove City Church. Tso said, “translators were available at the clinics, or a phone call away, for 55 different languages and dialects.” The church is within walking distance for many residents who live in AsiaTown, which made it more convenient for them to get vaccinated if they did not have access to transportation or had trouble scheduling an appointment to receive the vaccine at other sites.

In addition to the challenges of a language barrier and transportation, lack of childcare can also be an obstacle preventing adults from getting vaccinated. However, having the pop-up vaccination event on a Sunday helped. Tso said, “I watched multiple baby strollers and toddlers while their moms were getting vaccinated.”

The day for people to receive the second dose of COVID-19 vaccine fell on Mother’s Day, so ASIA and its partners promoted a pop-up clinic as a Mother’s Day event for people to come with their families. Nearly 200 people returned to Cove City Church in the pouring rain on May 9, 2021, to get vaccinated. Many AsiaTown residents brought their mothers to receive the vaccine, and families who received vaccines together celebrated with a special photo at the site. For the two pop-up vaccination events, nearly 400 people were fully vaccinated.

ASIA remains committed to COVID-19 vaccination efforts. The organization’s International Community Health Center provides vaccines and testing in Cleveland and Akron. Tso emphasizes ASIA’s determination to help protect people – “We don’t vaccinate just for ourselves, we vaccinate for our family, friends, and neighbors. When we strive together for immunity, we protect our community and show our love to the important people in our lives.”

Partnership for a Healthy Lincoln (PHL), in Lincoln, Nebraska, knew that in order to promote vaccination to COVID-19 to racial and ethnic minority communities and help them overcome vaccine hesitancy, the message needed to come from well-known, respected, and trusted members of their communities.

Through supplemental grant funds from CDC’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program, PHL supported outreach efforts by funding community health workers and vaccine coordinators within specific cultural partner organizations to provide evidence-based education, dispel misinformation, and offer vaccine clinics. PHL also launched a compelling messaging campaign in April 2021 that promotes vaccination in those communities by collaborating with Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian cultural and community centers, faith leaders, and community advocates. The messaging campaign continues and includes digital ads, social media, bus and billboard campaigns, radio, and TV.

In partnership with members of Lincoln’s Black clergy, PHL supported vaccination clinics and promoted public awareness through multiple mediums. Billboards featuring Black clergy in diverse neighborhoods brought positive attention within faith communities.

Messaging featuring a Black Pastor and prominent Black community members on the sides of Lincoln’s city buses resulted in television news coverage on Nebraska’s largest CBS affiliate, KOLN/KGIN. The station has the most watched news programs in Lincoln, and its coverage area stretches across 42 counties in southern and central Nebraska – almost two-thirds of the state’s geographical land area.

Vaccine clinics in local Hispanic churches hosted by PHL’s partner, El Centro de las Americas, reached additional members of the Spanish-speaking community. Billboards and bus sides featured trusted Hispanic doctors, teachers, and community advocates promoting vaccination in Spanish.

Internet video and banner ads featuring Black and Hispanic health care professionals and community advocates resulted in a substantial increase of new visits to PHL’s English and Spanish vaccine information pages on the PHL website, HealthyLincoln.org. (click pictures to play). As the ad campaign began in April 2021, there were 33 combined visits to those pages. One month later, combined visits jumped to 2,835.

“Our lives matter. Black Americans are more likely to get infected and die from COVID, but we don’t have to,” said Sanford Bradley, Sr., an outreach specialist and nonprofit director, in a public service announcement from PHL.

“As a doctor, I was one of the first to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. It protects me, my family, and my patients,” said Dr. Horacio Alvarez Ramirez (in Spanish) in another public service announcement. “It’s our best chance to return to normal.”

Korean immigrants and the wider Asian community faced significant communication obstacles when New York City began administering COVID-19 vaccines in the spring of 2021. Language barriers impacted communication among the vaccine administrators, registration staff, and Asian community members. Additionally, a lack of digital literacy among older Asians was a challenge. Many did not have an internet connection or an email account to register in the vaccination appointment portal. Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York (KCS) stepped in to help bridge these gaps.

KCS’s community engagement activities, which included hosting a New York City vaccine center, provided culturally sensitive services to community members. KCS workers educated them about the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination and helped address any concerns. A key issue with getting people vaccinated was helping them with the registration process. Registrations were done online and over the phone, but many older Korean and Chinese immigrants didn’t have access to computers. KCS set up a phone line for people to call and ask questions and/or get registered for a vaccination appointment. The “KCS Vaccine Angel Project” enhanced those efforts. Two staff members, along with three to four volunteers, responded to inquiries about COVID-19 vaccines. They answered questions about safety and side effects, made appointments, and followed up after vaccination. Through this project, KCS reached out to over 2,000 people during a two-month period in the spring of 2021 and directly set up vaccination appointments for about 750 people.

KCS provided additional help with adult vaccinations as the rollout began. An outreach team went into the community and provided information on local testing and vaccination sites. KCS hosted a vaccine center operated by Centers Urgent Care in the borough of Queens. The site was open 7 days a week and provided around 160 daily doses of COVID-19 vaccine during the spring of 2021. When demand for vaccinations started to go down during the summer, the vaccine center moved from appointment-based operations to accepting walk-in appointments.

KCS partnered with Hyo Shin Bible Presbyterian Church of Flushing, New York (in Queens), where parents inquired about COVID-19 vaccines when they became available for children 5 years and older. KCS provided Korean speakers to the Church’s after school academy and Sunday bible school to answer questions on vaccine safety and vaccine truck hours. Providing Korean speakers addressed a significant language barrier, which aided vaccination efforts. KCS also hosted several town halls with licensed doctors and medical experts to answer questions about COVID-19 vaccines in many languages, including Korean, Hindi, Mandarin, and Spanish.

KCS’s website declares, “KCS’s mission is to be a bridge for Korean immigrants and the wider Asian community to fully integrate into society and overcome any economic, health, and linguistic barriers so that they become independent and thriving members of the community.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, KCS realized the importance of community centers as convenient, comfortable, and trusted venues. These centers became vital to racial and ethnic minority communities. Community health workers speaking their languages are great resources to promote vaccination. All of these initiatives, including street outreach activities where masks and sanitizers are given out, reinforce the trust in Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York as an important community partner.

The Eastern Crescent area of Austin, Texas reports the highest rates of poverty, unemployment, and uninsured individuals in the metro area. The population of the Eastern Crescent is historically and primarily made up of communities of color. The ZIP codes within the Austin Metropolitan area which have a majority Latino population fall in the Eastern Crescent.

Throughout the pandemic, rates of COVID-19 infection in the Eastern Crescent have exceeded those in the rest of the Austin area by more than 100 cases per 100,000 members of the population. The Eastern Crescent reported lower vaccination rates than the rest of the Austin area, as well. In May 2021 – when nearly 57% of all Austin area residents had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine – only 44% of residents in the Eastern Crescent had received a vaccine dose.

Access, more than attitudes, was a key driving force in the vaccination disparities in the Austin area. While the total population living in the Eastern Crescent is roughly equivalent in size to the population living in the rest of the Austin area, there are 26% fewer vaccine providers in the Eastern Crescent than in the rest of the Austin area. In fact, 13 of the Eastern Crescent’s 40 ZIP codes do not have a single COVID-19 vaccine provider.

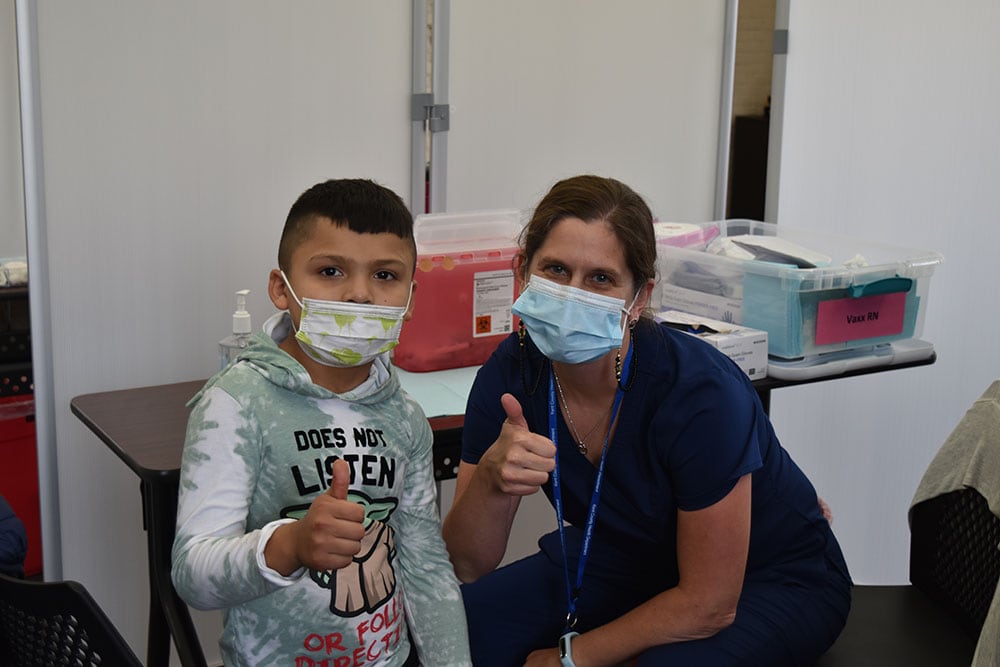

To address these disparities in access, El Buen Samaritano (El Buen), an outreach ministry of the Episcopal Diocese of Texas serving the Latino community of Central Texas, has specifically focused its vaccination campaign (the clinics as well as related outreach and education efforts) on the Eastern Crescent area.

El Buen was founded in 1987 to improve access to food and health services while focusing on the systemic factors and social determinants of health that negatively affect Latinos and immigrants. El Buen provides an array of programs and services that enables the community to engage in a critical social support network via adult education, workforce development, youth afterschool academic support, leadership and development summer camps, health access and promotion, financial and rental assistance, and food security (in the form of a year-round food pantry).

El Buen and its partner organizations have a long history serving the Latino and low-income communities in Central Texas and are trusted providers. While El Buen works with clients throughout Central Texas in its programs, 88% of the people who have received vaccines at El Buen’s vaccine events have been residents of the Eastern Crescent area.

These vaccine clinics have generated significant demand, with wait times for drive-through events exceeding 90 minutes. To maintain client satisfaction during the wait time, organizers tied in themed events, such as celebrations for Dia de los Muertos and Thanksgiving.

The results of this tailored outreach have improved vaccination rates. As of January 2022, more than 75% of the Eastern Crescent’s residents had received at least one vaccine dose compared to only 44% in May 2021 and comparable to the 75% one-dose vaccination rate in Texas at that same time.

El Buen regularly surveys its clients—the vast majority of whom are Latino and residents of the Eastern Crescent—and in the most recent survey, only 18% of respondents indicated they remain unvaccinated and hesitant to become vaccinated in the future. Additionally, clients at El Buen’s vaccine clinics are twice as likely to indicate a transportation, time, childcare, or eldercare constraint as a reason for delaying their vaccination than distrust in the vaccines or healthcare industry.

Despite the improvements in vaccination uptake and vaccine confidence among its clients, El Buen remains aware of the continued need for vaccine access and work still to be done. The Eastern Crescent’s vaccination rates still lag behind the rest of Austin, where nearly 85% of the population have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose.

El Buen continues to refine its approach to reach the residents of the Eastern Crescent who remain unvaccinated, as well as to provide booster doses to those who have been vaccinated. Outreach campaigns for vaccination clinics are integrated into the organization’s other activities and focus on Spanish-language, culturally relevant communication. By conducting its vaccine clinics at a time and location that is convenient for its clients, El Buen strengthens its position as a trusted community partner to engage individuals and increase vaccine uptake.

To solve problems facing individual communities, community-level outreach and collaboration are key. They are also the foundational principles for the Partnering for Vaccine Equity program, which supports more than 500 organizations in a shared effort to increase vaccine confidence and uptake via influential messengers. Finding people and organizations that are trusted by the community and who can provide culturally appropriate information that resonates with the community of interest is critical.

The National Network of Public Health Institutes (NNPHI) supports projects that address the systemic disadvantages experienced by racial and ethnic minority groups, rural communities, and communities that face a disproportionate burden of adverse outcomes from public health threats. In the fall of 2021, NNPHI announced funding (via CDC) for “National Infrastructure for Mitigating the Impact of COVID-19 within Racial and Ethnic Minority Communities: The Vaccine Equity Project.” The request for proposals (RFP) prompted a robust response from community-based organizations.

After a very competitive proposal process, NNPHI selected five organizations as subrecipients of its CDC funding, each receiving $600,000: the African Family Health Organization, Project HEALINGS in Minnesota, The Dolores Huerta Foundation, The Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan, and Public Health Solutions. Through the Vaccine Equity Project, these organizations provide resources and support to their communities of focus – including racial and ethnic minority groups (such as Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, and American Indian/Alaska Native Tribal populations), as well as immigrant and rural communities.

To maximize awareness and interest among community-based organizations, NNPHI sent out “heads up” messages through social media a month in advance so that community-based organizations would be ready to apply. NNPHI also promoted the funding opportunity with a graphic, which included multiple languages and shadows of faces in profile. This graphic intended to capture attention and highlight that the money was intended for organizations that serve a wide array of racial and ethnic minority groups and that may not have considered applying for opportunities like this in the past.

NNPHI held three two-hour open online forums with potential applicants to help them understand what they needed to do and how to write up proposed strategies to engage communities and improve vaccination uptake. The organization also made sure the RFP was written at an appropriate reading level, used inclusive language, and was free of technical terms and jargon by pilot testing the RFP with community partners. NNPHI developed detailed guidance on how community-based organizations could demonstrate their creative ideas and deep knowledge of their communities. For example, the guidance offered the option of submitting a video narrative instead of or in addition to text.

When it was ready, the RFP was released through NNPHI’s network of public health institutes, on social media, through subject matter experts, and other collaborators. The distribution email asked recipients to forward the RFP to organizations they collaborate with, along with community representatives. NNPHI also set up a dedicated inbox to field questions about the RFP.

Learn more about The Vaccine Equity Project and the award winners here.

To send questions or comments about the program, send an e-mail to PHEBranch@cdc.gov.