How Do I Prescribe PrEP?

- There are three US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved PrEP medications.

- PrEP is highly effective when taken as prescribed.

- Any licensed prescriber can prescribe PrEP.

- Assess your patients to identify candidates for PrEP.

- PrEP is a safe method for HIV prevention.

- PrEP isn’t right for every patient.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has comprehensive guidelines for prescribing PrEP.

PrEP is short for pre-exposure prophylaxis. It is the use of antiretroviral medication to prevent getting HIV. PrEP is used by people without HIV who may be exposed to HIV through sex or injection drug use.

Consider PrEP as part of a comprehensive prevention plan that includes a discussion about using PrEP as prescribed, condom use, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and other risk-reduction methods.

Three medications have been approved for use as PrEP by the FDA. Two consist of a combination of drugs in a single oral tablet taken daily. The third is a medication given by injection every 2 months.

- Emtricitabine (F) 200 mg in combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) 300 mg (F/TDF—brand name Truvada® or generic equivalent).

- Emtricitabine (F) 200 mg in combination with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) 25 mg (F/TAF—brand name Descovy®).

- Cabotegravir (CAB) 600 mg injection (brand name Apretude®).

These medications are approved to prevent HIV in adults and adolescents weighing at least 77 lb (35 kg) as follows:

- Daily oral PrEP with F/TDF is recommended to prevent HIV among all people at risk through sex or injection drug use.

- Daily oral PrEP with F/TAF is recommended to prevent HIV among people at risk through sex, excluding people at risk through receptive vaginal sex. F/TAF has not yet been studied for HIV prevention for people assigned female at birth who could get HIV through receptive vaginal sex.

- Injectable PrEP with CAB is recommended to prevent HIV among all people at risk through sex. CAB is given as an intramuscular injection. CAB for PrEP is started by administering the first injection followed by a second injection 1 month after the first. CAB injections are given every 2 months thereafter.

When taken as prescribed, both oral1-3 and injectable4,5 PrEP reduce the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99%. Oral PrEP has also been shown to reduce the risk of getting HIV from injection drug use by at least 74%, when taken as prescribed.6,7

| Transmission Route | Type of PrEP | Effectiveness Estimate | Interpretation |

| Sexual | Oral PrEP1-3 | ~99% | Consistently using PrEP as prescribed ensures maximum effectiveness. |

| Injection Drug Use | Oral PrEP6,7 | ≥74% | This estimate is based on tenofovir alone and not necessarily when taken daily. Two-drug oral therapies and taking oral PrEP medication daily may increase its effectiveness. |

Summaries of clinical trials showing the efficacy and safety of both oral and injectable PrEP are included in Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2021 Update—A Clinical Practice Guideline.8 For more information on evidence related to daily, consistent, and on-demand oral PrEP use, visit CDC’s HIV Risk and Prevention Estimates page.

Tell all your sexually active patients about PrEP and how it can protect them from getting HIV. Telling all sexually active patients about PrEP will increase the number of people who know about PrEP and may also help patients overcome embarrassment or stigma that could prevent them from telling their health care provider about their HIV risk factors.9-14 Prescribe PrEP to anyone who asks for it, including sexually active adults and adolescents who do not report HIV risk factors.

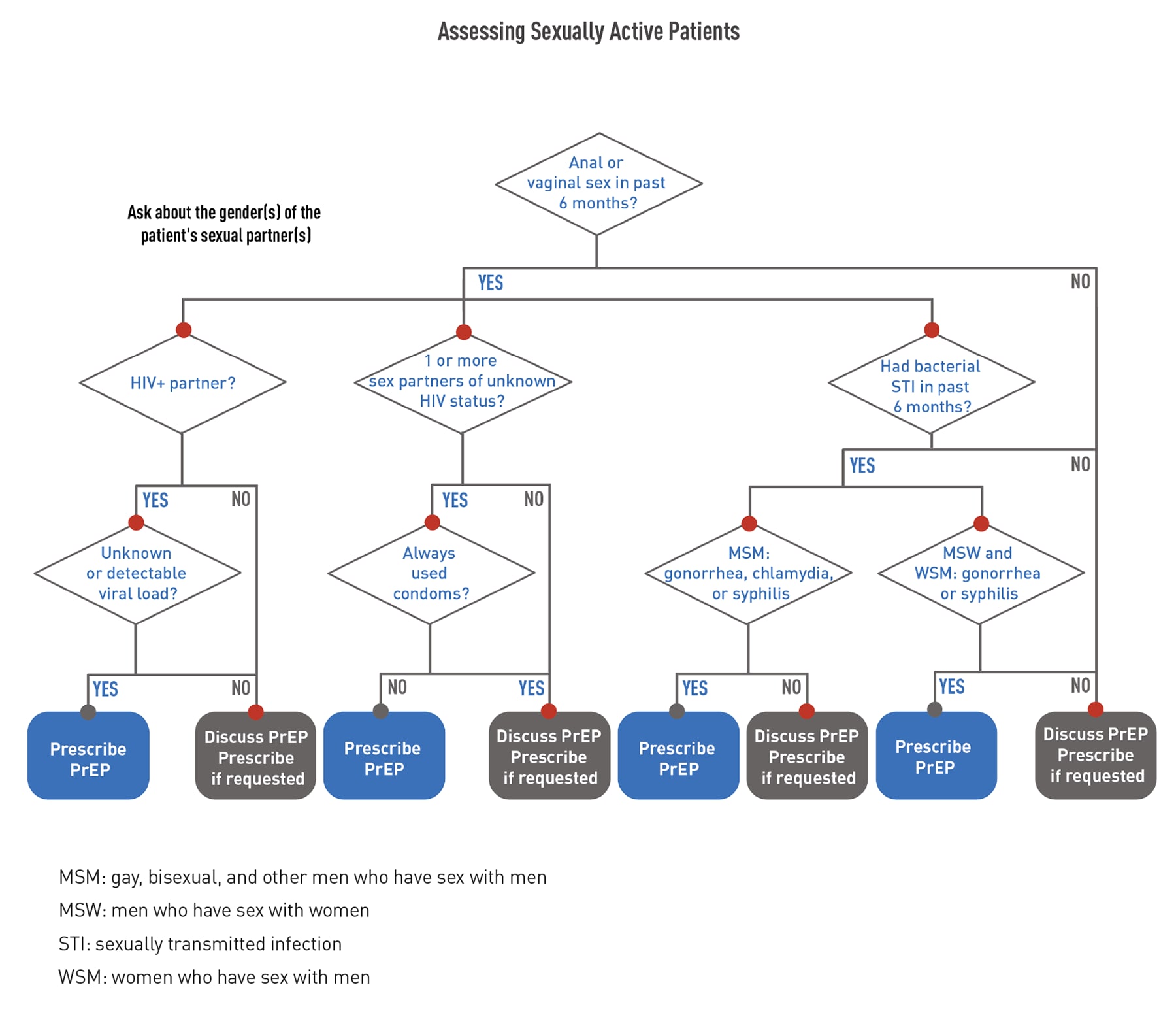

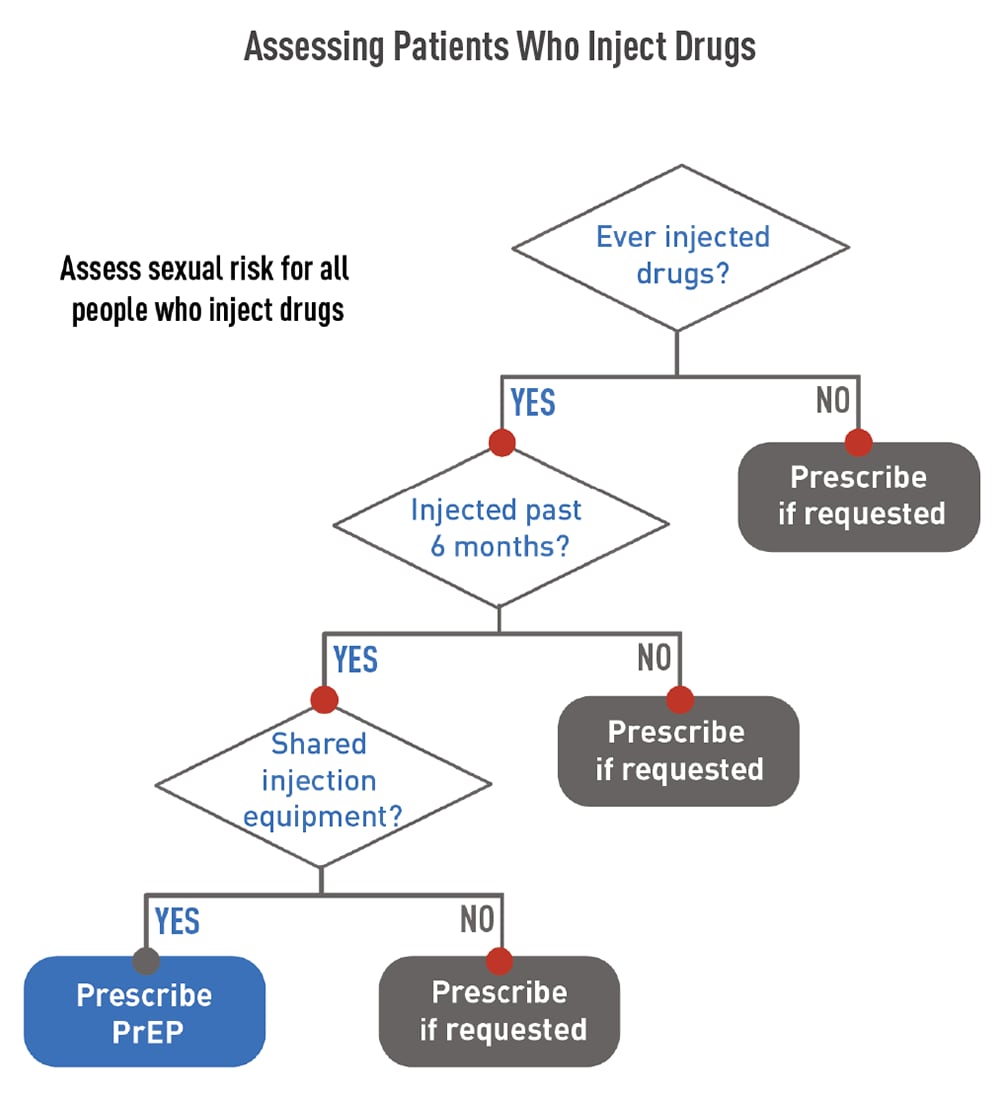

Whether or not a patient asks for PrEP, it is important to take a sexual and substance use history. This information is essential to understand each patient’s risk of getting HIV, if PrEP might be right for them, and what other risk-reduction services should be offered.

Sexual health is an essential element of overall health and wellbeing, yet health care providers and patients often do not discuss this topic. Learn how you can help to remove the stigma around discussing sex and normalize these conversations.

Use the following flowcharts to assess patients before offering PrEP.

Before prescribing PrEP, perform the required baseline assessments. Click through the tabs below to access information about each type of assessment.

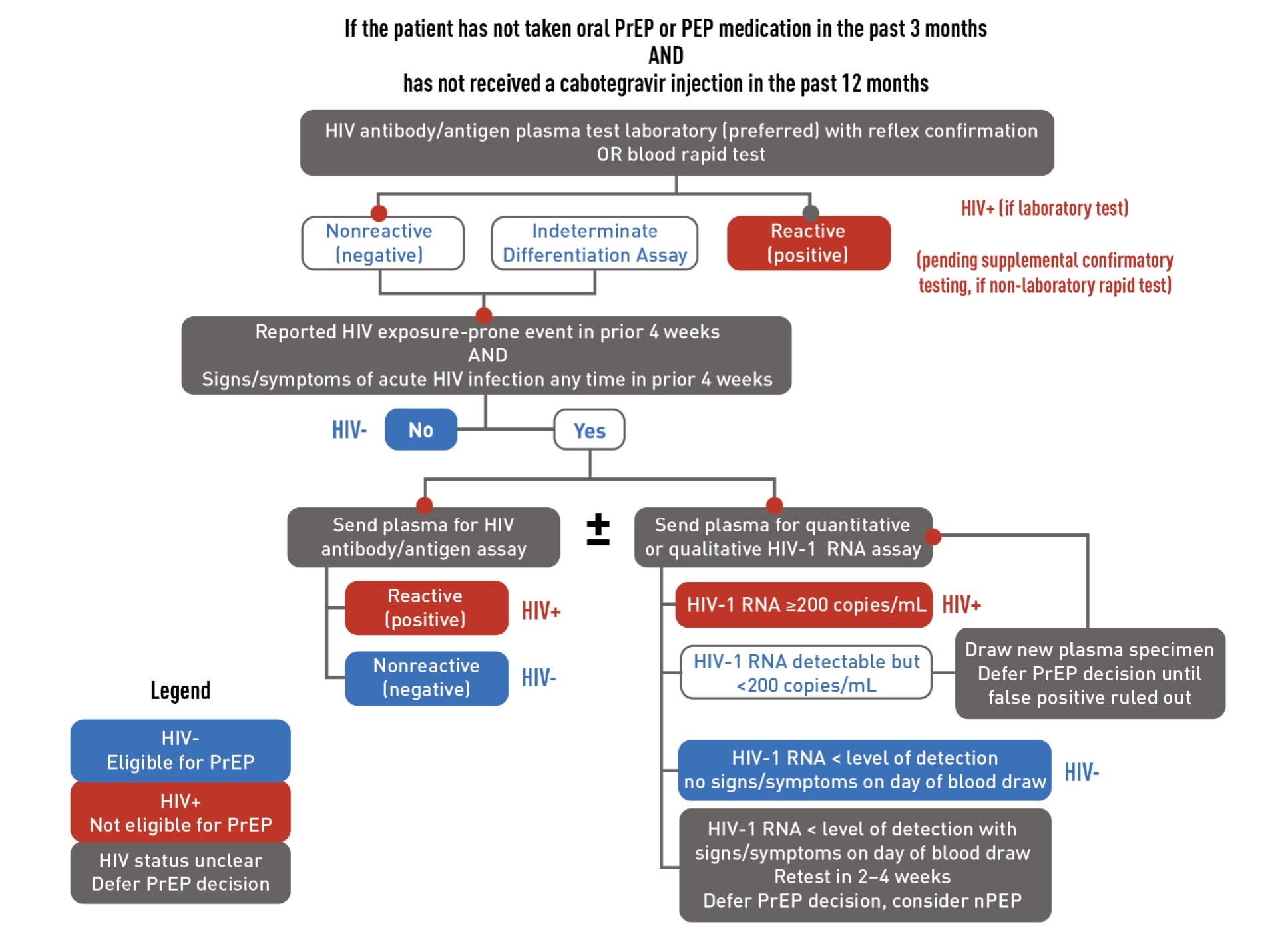

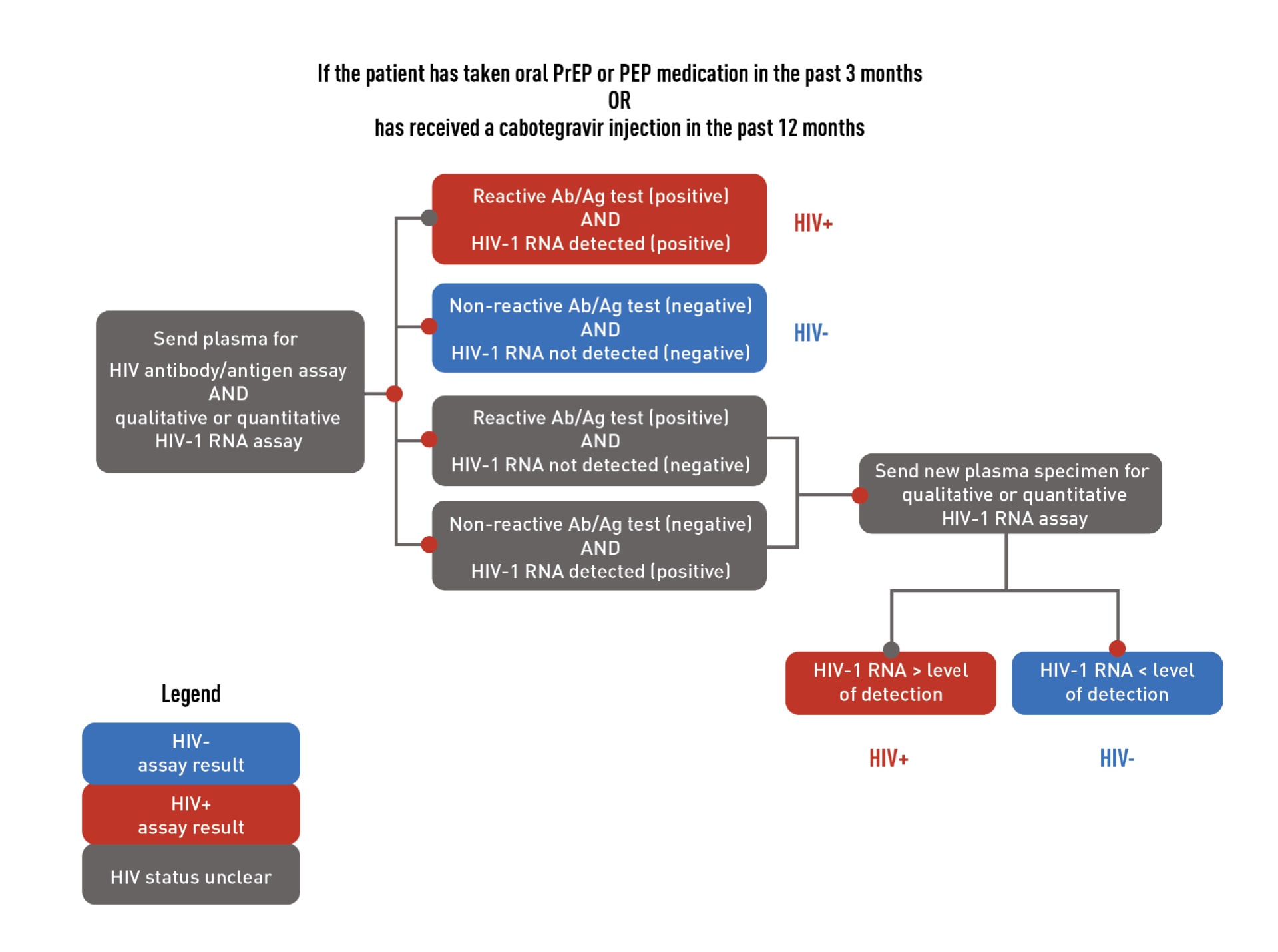

HIV testing is required to confirm that patients do not have HIV when they start taking PrEP. Required testing differs for people who have or do not have recent antiretroviral PrEP or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) use. Recent use is defined as taking oral PrEP in the last 3 months or receiving a CAB injection in the last 12 months. Download the flowcharts below to learn more about required HIV testing.

- For patients who are starting or restarting PrEP after a long stop, test using an HIV antigen/antibody test (a laboratory-based test is preferred).

- For patients who are taking or have recently taken PrEP, test using an HIV antigen/antibody test and a qualitative (or quantitative) HIV-1 RNA test.

Download the flowcharts below to learn more about required HIV testing.

If a patient has a negative antigen/antibody test and an undetectable HIV-1 RNA test (if applicable) confirming they do not have HIV, PrEP can be prescribed. However, if a patient has both a positive antigen/antibody test and a detectable HIV-1 RNA test confirming that they have HIV, link that patient to HIV care and treatment. If results are discordant or ambiguous, a new blood specimen should be obtained for retesting, and PrEP should not be prescribed until true HIV status is confirmed.

You can accomplish the required HIV testing by one of two methods:

- Drawing blood, sending it to a laboratory for testing, and getting the results before prescribing or continuing PrEP; or

- Using a rapid, point-of-care, FDA-approved fingerstick HIV antigen/antibody blood test and drawing blood to send for laboratory testing. PrEP can be prescribed or continued based on a negative rapid antigen/antibody test result while awaiting laboratory test results.

Avoid using oral rapid tests to screen for HIV when considering offering or continuing PrEP because they are less sensitive than blood tests and may not detect recent HIV infection.16 A listing of FDA-approved HIV tests, specimen requirements, and time to detection of HIV infection is available from CDC.

Since PrEP is indicated for people at risk of HIV acquisition, acute HIV infection should be suspected in patients who were recently exposed. Ask all PrEP candidates with a negative or indeterminate result on an HIV test about whether they have experienced any signs or symptoms of viral infection in the preceding month or on the day of evaluation.

If your patient reports signs/symptoms of acute HIV infection within the prior 4 weeks, the following options are suggested:

- Test the patient with a combination antibody/antigen assay. Ideally, use a laboratory-based method. If a point-of-care antigen/antibody test is used and is non-reactive (negative), PrEP can be started while waiting for confirmatory laboratory test results.

- Test the patient’s HIV-1 RNA. If the patient has a measurable viral load that is <200 copies/mL, they may have HIV or a false-positive test result. PrEP should be deferred while testing is repeated on a new blood specimen. If the viral load is below the level of detection of the assay for the second blood specimen, and the patient has no signs/symptoms on that day, the first HIV-1 RNA test result was a false positive. The patient is considered to not have HIV, and PrEP can be started.

Tests to screen for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis are recommended for all sexually active adults before starting oral or injectable PrEP.

Oral PrEP. For patients taking F/TDF or F/TAF as PrEP, assess kidney function before starting PrEP.

When used as PrEP, tenofovir can cause decreases in kidney function that are generally small, usually remain within the normal range, and are of no known clinical significance.16,17 These small decreases typically return to earlier levels when the patient stops taking the medication.18,19 Occasional cases of acute kidney failure, including Fanconi’s syndrome, have occurred.17,20-23 Therefore, all patients considered for oral PrEP must have their kidney function assessed at PrEP initiation and periodically thereafter so that oral PrEP can be stopped, if necessary.

Kidney function should be assessed by using the Cockcroft-Gault formula with the patient’s serum creatinine value to calculate their estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl)24:

- F/TDF is approved for use in people with eCrCl >60 mL/min.

- F/TAF is approved for use in people with eCrCl ≥30 mL/min.

Injectable PrEP. For patients taking CAB, kidney assessments are not needed.

Emtricitabine and tenofovir can be used to treat active hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. However, in people with active HBV, stopping these medicines can result in a rebound of HBV replication leading to liver damage. HBV infection is not a contraindication to PrEP, but all people considered for oral PrEP with F/TDF or F/TAF must be screened for HBV. Patients with active HBV infection should be educated about the risks of stopping oral PrEP without appropriate follow-up so that if they stop using oral PrEP, their liver function can be closely monitored for reactivation of HBV replication.

For patients taking F/TAF as oral PrEP, assess cholesterol and triglyceride levels before starting PrEP.

PrEP has not caused serious short- or medium-term safety concerns.1,4,25,26

Oral PrEP. F/TDF as PrEP is considered generally safe for people who are pregnant or breast/chestfeeding.27 If a patient who is or may become pregnant has concerns, discuss those concerns with the patient. Then, decide together if the risk of getting HIV through sex or injection drug use is sufficiently high to use PrEP, knowing that pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of getting HIV.28

Daily oral PrEP with F/TAF is recommended to prevent HIV among people at risk through sex, excluding people at risk through receptive vaginal sex. F/TAF has not yet been studied for HIV prevention for receptive vaginal sex.

Because F/TDF and F/TAF are eliminated by the kidneys, prescribe these PrEP medications only to patients without severe kidney impairment. Co-administer oral PrEP with care in patients taking other drugs eliminated by the kidneys. Examples of drugs eliminated by the kidneys include acyclovir, adefovir dipivoxil, cidofovir, ganciclovir, valacyclovir, valganciclovir, aminoglycosides, and high-dose or multiple nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drugs that decrease kidney function may also increase serum concentrations of tenofovir or emtricitabine.27,29 Instead of oral PrEP, CAB injections are recommended for people who have serious kidney disease with eCrCl <30 mL/min.

Injectable PrEP. In clinical trials, injection site reactions (e.g., pain, tenderness, local skin swelling) were frequently reported following CAB injections.30 Patients should be informed that these reactions are common, are generally mild or moderate, and do not last long.

Although there are PrEP medication and dosing options to meet patients’ differing needs, PrEP isn’t right for some patients.

Oral PrEP isn’t the right choice for:

- People with HIV. Health care providers must confirm that patients are HIV negative before starting PrEP. Excluding people with acute HIV infection is critically important so that they do not develop drug-resistant HIV because they took PrEP medication while in the early stages of HIV. F/TDF and F/TAF are appropriate parts of a regimen to treat HIV but must be combined with additional antiretrovirals to provide effective treatment.

- People with severe kidney impairment. Before prescribing oral PrEP, providers should confirm that each patient’s eCrCl is high enough, using the Cockcroft-Gault formula:

- ≥60 mL/min for F/TDF or F/TAF.

- ≥30 mL/min for F/TAF.

2-1-1 dosing of oral PrEP is also known as event-driven, intermittent, on-demand, or coitally timed PrEP. Although this dosing option can be used by adult men who have sex with men (MSM) prescribed F/TDF, it is not approved by the FDA and is not recommended by CDC.

It is not right for:

- People other than adult MSM. The 2-1-1 dosing method has only been studied in adult MSM.

- People with active HBV infection. Episodic F/TDF exposure can cause hepatic flares in people with active HBV infection and should be avoided.

Injectable PrEP isn’t right for:

- People with HIV. Health care providers must confirm that patients are HIV negative before starting PrEP. Excluding people with acute HIV infection is critically important so that they do not develop drug-resistant HIV because they took PrEP medication while in the early stages of HIV infection. CAB must be combined with other antiretroviral medication to provide effective treatment for people with HIV.

- People with sensitivity to CAB. CAB should not be given to people with a history of hypersensitivity reaction to CAB.

You can access CDC’s comprehensive guidelines for prescribing PrEP in A Clinical Practice Guideline for PrEP8 and the Clinical Providers’ Supplement for PrEP.27

The Clinical Providers’ Supplement for PrEP contains additional tools for clinicians providing PrEP, such as

- Patient/provider checklists.

- Patient information sheets.

- Provider information sheets.

- HIV risk screening assessments for gay, bisexual, and other MSM and people who inject drugs.

- Supplemental counseling information.

- Billing codes.

- Practice quality measures.

Routine HIV screening is endorsed by:

The US Preventive Services Task Force has given PrEP a grade A recommendation.8 This grade indicates that their review found high certainty that the net benefit of this service is substantial. For more information, view the full recommendation rationale.

If you have questions about PrEP or need prescribing advice, consult the National Clinician Consultation Center PrEPline by calling 1-855-448-7737 (Monday–Friday, 9:00 AM–8:00 PM ET).

1 Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Update of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820-829. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6107918/

2 Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng J-H, Rower JE, et al. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2013;29(2):384-390. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3552442/

3 Mayer KH, Molina, J-M, Thompson, MA, et al. Emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (DISCOVER): primary results from a randomized, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):239-254. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9665936/

4 Landovitz RJ, Donnell D, Clement ME, et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):595-608. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2101016

5 HPTN 084 study demonstrates superiority of CAB LA to oral TDF/FTC for the prevention of HIV. HPTN: HIV Prevention Trials Network; November 9, 2020. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.hptn.org/news-and-events/press-releases/hptn-084-study-demonstrates-superiority-of-cab-la-to-oral-tdfftc-for

6 Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;381(9883):2083-2090. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(13)61127-7/fulltext

7 Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. The impact of adherence to preexposure prophylaxis on the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. AIDS. 2015;29(7):819-824 https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2015/04240/The_impact_of_adherence_to_preexposure_prophylaxis.8.aspx.

8 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

9 Qiao S, Zhou G, Li X. Disclosure of same-sex behaviors to health-care providers and uptake of HIV testing for men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(5):1197-1214. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6142161/

10 Petroll AE, Mosack KE. Physician awareness of sexual orientation and preventive health recommendations to men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(1):63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4141481/

11 US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Illicit Drug Use. Accessed August 20, 2013, https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

12 McDonell MG, Graves MC, West II, et al. Utility of point of care urine drug tests in the treatment of primary care patients with drug use disorders. J Addict Med. 2016;10(3):196. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4880495/

13 Chasnoff IJ, Landress HJ, Barrett ME. The prevalence of illicit-drug or alcohol use during pregnancy and discrepancies in mandatory reporting in Pinellas County, Florida. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(17):1202-1206. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199004263221706

14 White D, Rosenberg ES, Cooper HL, et al. Racial differences in the validity of self-reported drug use among men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:146-153. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4104302/

15 Deutsch MB, Glidden DV, Sevelius J, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in transgender women: a subgroup analysis of the iPrEx trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(12):e512-e519. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352301815002064

16 Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. Renal function of participants in the Bangkok tenofovir study—Thailand, 2005–2012. Clin infect Dis. 2014;59(5):716-724. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/59/5/716/2895408?login=true

17 Mugwanya KK, Wyatt C, Celum C, et al. Changes in glomerular kidney function among hiv-1-uninfected men and women receiving emtricitabine–tenofovir disoproxil fumarate preexposure prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):246-254. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4354899/

18 Emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Prescribing information. Teva Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2020. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.tevahivgenerics.com/globalassets/emtricitabine/pdfs/tg-42450_emtricitabine-and-tenofovir-disoproxil-fumarate-tablets-promo-pi-for-use-electronically.pdf

19 Truvada. Prescribing information. Gilead Sciences; 2020. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.gilead.com/-/media/files/pdfs/medicines/hiv/truvada/truvada_pi.pdf

20 Antoni G, Tremblay C, Charreau I, et al. On-demand PrEP with TDF/FTC remains highly effective among MSM with infrequent sexual intercourse: a sub-study of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Presented at: IAS Conference on HIV Science; July 23-27, 2017; Paris, France.

21 Saag MS, Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2018;320(4):379-396. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6415748/

22 Mugwanya KK, Wyatt C, Celum C, et al. Changes in glomerular kidney function among HIV-1-uninfected men and women receiving emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate preexposure prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):246-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4354899/

23 Tang EC, Vittinghoff E, Anderson PL, et al. Changes in Kidney Function Associated With Daily Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine for HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Use in the United States Demonstration Project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(2):193-198. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5762266/

24 Wassner C, Bradley N, Lee Y. A review and clinical understanding of tenofovir: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus tenofovir alafenamide. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2020;19:2325958220919231. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7163232/

25 Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399-410. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3770474/

26 Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immun Def Syndr. 2014;66: 340-348. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4059553/

27 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update: clinical providers’ supplement. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-provider-supplement-2021.pdf

28 Thompson KA, Hughes J, Baeten JM, et al. Increased risk of female HIV-1 acquisition throughout pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective per-coital act analysis among women with HIV-1 infected partners. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:16-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5989601/

29 US Preventive Services Task Force. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2203-2213. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2735509

30 Apretude. Prescribing information. ViiV Healthcare; 2021. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://gskpro.com/content/dam/global/hcpportal/en_US/Prescribing_Information/Apretude/pdf/APRETUDE-PI-PIL-IFU.PDF