What to know

Meet our people, our partners, and see the challenges and successes of creating a world that is both healthier for all and more secure for Americans where they live, work, and play.

Articles

Stopping an Outbreak in Its Tracks: Polio Response in Mozambique

Photo Essay: Measles, a Dangerous but Preventable Childhood Illness

Photo Essay: Urgently Working to Find and Vaccinate Children Worldwide

Partnering to Increase Hepatitis B Birth Dose Vaccination in Africa

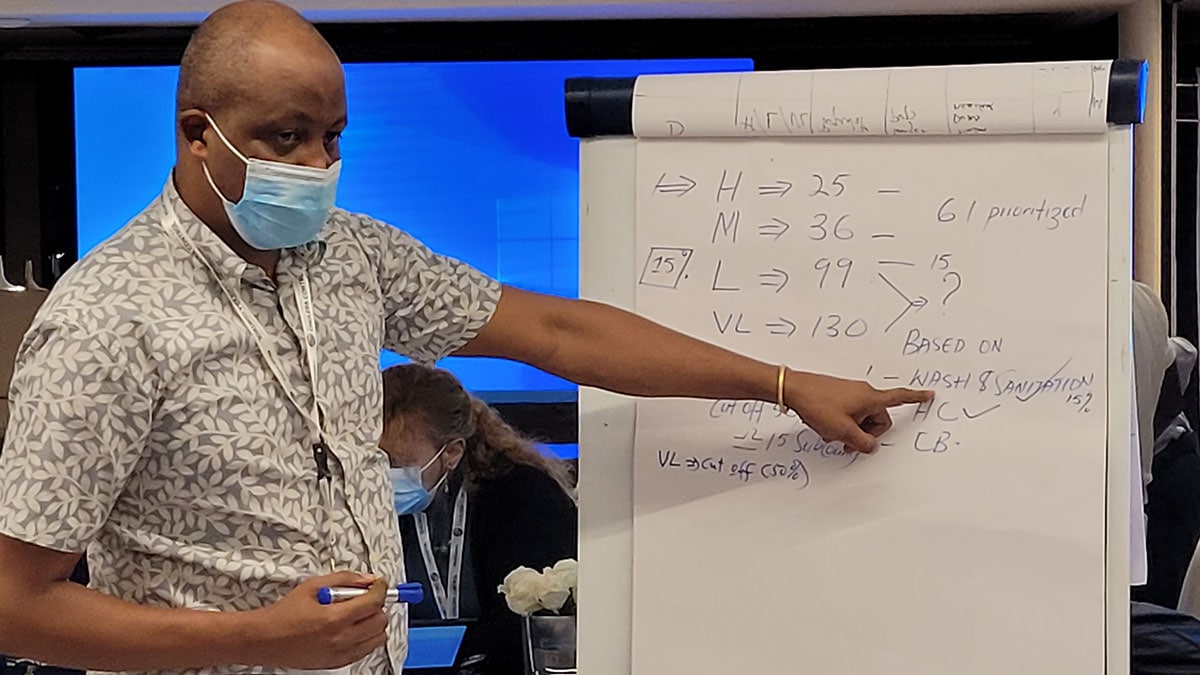

Multi-year Planning for Oral Cholera Vaccines May Help Prevent Deadly Outbreaks

CDC Evaluates and Shares Lessons Learned from HPV Vaccine Introduction in Three Countries