Tracking Lassa Fever Across Three Countries

April 30, 2019

Team members review records as part of a health evaluation in Nigeria. Photo: Tamuno-Wari Numbere

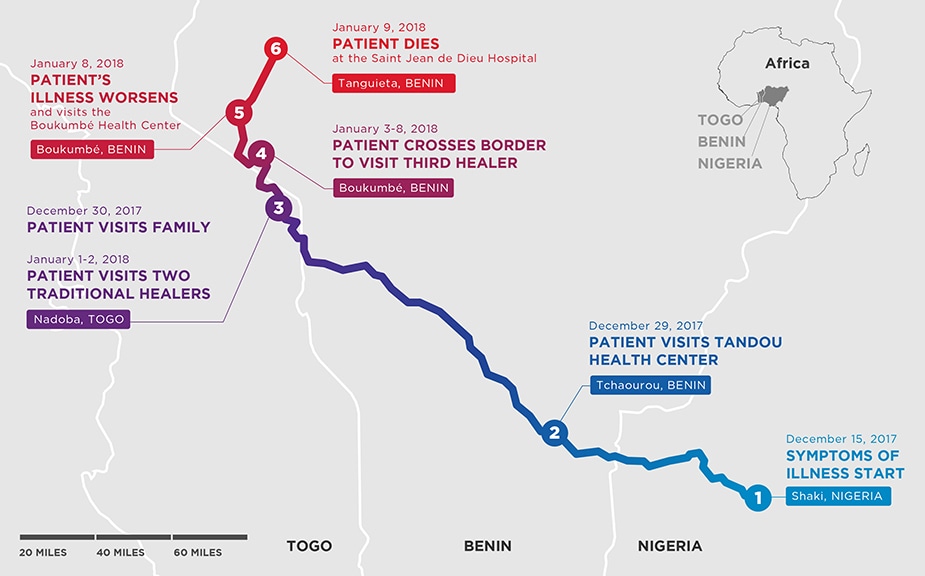

When a Beninese migrant worker fell ill in Nigeria in December 2017, he decided to return to his parents’ home in Togo for care. His condition deteriorated during his trip through Benin.

On his trip he stopped at Tandou Health Center in Tchaourou, Benin, was attended to by two health care workers, and continued his trip. He arrived home in Nadoba, Togo but his condition worsened and he went to several traditional healers near his home in Togo, as well as another health center in Boukombé, Benin, which referred him to the nearest hospital, Saint Jean de Dieu Zone Hospital in Tanguiéta, Benin. Here the attending doctor immediately suspected a hemorrhagic fever.

The patient was placed in isolation and a blood sample was sent to the national laboratory of Cotonou for diagnostic testing. He died the following day and laboratory tests confirmed he had Lassa fever. Public health workers in Benin immediately notified their colleagues across the border in Togo, and worked together to identify and follow fifty-five contacts, 23 in Togo and 32 in Benin.

This tragic story of a very sick man traveling across three countries caught the attention of Lesley Chace, CDC’s support lead for Francophone West Africa Field Epidemiology Training Programs (FETP). She wondered if the man had infected others on his journey and if Nigeria and Benin were communicating with each other about this epidemic-prone viral hemorrhagic fever. Nigeria had an ongoing Lassa fever outbreak that had peaked in October 2017. About 10 days after the man died, Benin declared a Lassa fever outbreak with 21 cases, including four deaths.

Lassa fever is endemic in many West African countries and shares some characteristics with Ebola. The last Lassa fever outbreak in Benin occurred in February 2017 and involved someone traveling from Nigeria. The frequent movement of people across the Benin-Nigeria and Benin-Togo borders makes it imperative for the countries to foster both formal and informal communication and information sharing.

CONNECTING ACROSS BORDERS

When the outbreak started, both Benin and Nigeria had established successful FETPs that, with support from CDC, allowed information sharing and collaboration, an opportunity Chace wanted to capitalize on. For nearly 40 years, CDC has worked with ministries of health worldwide to develop country- and region-specific FETPs, building a cadre of more than 14,000 skilled disease detectives in over 70 countries. These FETPs, modeled after the CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service program, provide “boots on the ground” to respond to natural disasters and disease outbreaks, as well as to conduct hundreds of investigations, including surveillance evaluations and planned studies.

“With FETPs, we are building professional networks of similarly trained epidemiologists who can learn from each other and call on each other for epidemiology support,” said Chace. “This situation where a person with Lassa fevertraveled across borders presented an excellent opportunity to strengthen communication and collaboration in the face of a possible outbreak affecting several countries.”

CDC FETP Africa Region team lead Ken Johnson moved swiftly to link the leadership of Benin FETP to Nigeria FETP to share information. “Collaborations like these are made easier when there are FETPs in each country. A disease recognizes no borders, but joint efforts between two or more FETPs can facilitate a stronger response and save lives,” said Johnson. CDC’s efforts helped the two country programs to share information and situational updates that informed each country’s outbreak response and prevention efforts.

In West Africa, all three tiers of FETPs—Frontline, Intermediate, and Advanced—continue to lay the foundation for cross-country and regional collaborations to respond to disease threats and outbreaks. By sharing knowledge, skills, and experiences, FETPs and their trainees can potentially accomplish more than if they worked alone. Working collaboratively creates opportunities for countries to share best practices and lessons learned from epidemiology work. Through these exchanges, they gain a more harmonized approach and increased capacities to improve the health security of the population.