How Connection Equals Detection in Tanzania’s Cholera Outbreak

September 6, 2018

Tanzania Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC) meeting to coordinate response efforts.

November, 2017: A responder in Tanzania’s emergency operations center spots something alarming on a weekly laboratory report.

One of the country’s labs has identified a resurgence of cholera in the Kigoma region. Although other surveillance systems have not yet picked up the new cases, the lab report is clear, and the information triggers immediate action.

YOU CAN’T FIGHT WHAT YOU CAN’T SEE

Undetected, cholera can spread like wildfire in a community. Like many of the world’s most frightening diseases, confirming cases quickly and responding right away is key.

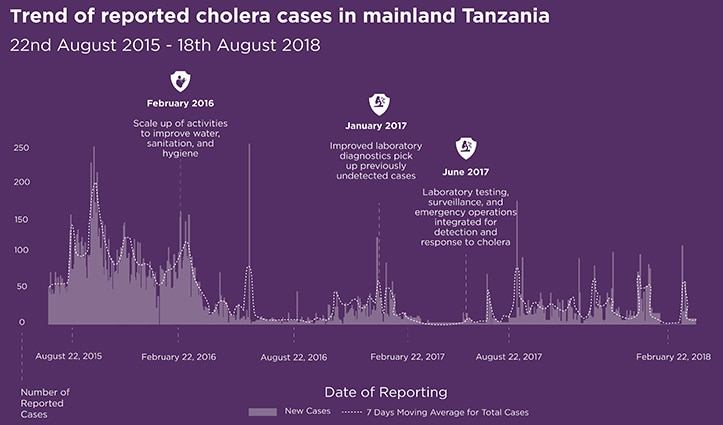

Tanzania has been battling a widespread outbreak of cholera since August 2015. It isn’t the first for the country, which has suffered periodic outbreaks since 1974, costing thousands of lives. At the time the current outbreak began, Tanzania had no emergency operations center to coordinate a response, limited electronic nationwide surveillance system to monitor diseases, and few laboratories with the ability to confirm and report suspected cases.

It was around this time that the world took a big step forward in stopping infectious diseases through the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA). Against a backdrop of real and present danger, with the momentum of the GHSA, Tanzania began working with global partners to strengthen its ability to respond. With the outbreak growing, Tanzania fought back by using the nationwide Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system and creating a Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC) to coordinate response efforts. Importantly, Tanzania also began improving the ability of its laboratories to accurately diagnose and report new cases.

BOOSTING LABS TO SAVE LIVES

Particularly at the local and regional levels, Tanzania’s laboratory workers had very limited access to the training and supplies needed to detect cholera. Many suspected cases were not being confirmed, and underreporting remained an urgent challenge. In partnership with CDC and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM), Tanzania’s Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly, and Children embarked on a program to boost the capacity of the country’s labs.

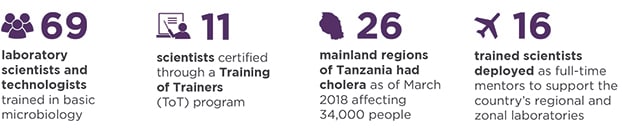

Experts conducted on-site training in basic microbiology, enabling lab workers to test for cholera and other priority diseases. Detailed checklists helped uncover and address critical gaps in processes, while master lists of standard operating procedures and supplies ensured that quality standards were being met. By June 2017, through GHSA funding, 69 laboratory scientists and technologists had been trained in basic microbiology, with 11 certified through a Training of Trainers (ToT) program and another 16 deployed as full-time mentors to support the country’s regional and zonal laboratories.

“THAT’S WHERE THE LAB DATA BECAME CRITICAL”

Thanks to these trainings, Tanzania’s labs are now able to accurately gather and report lifesaving outbreak information to the PHEOC. Between September and December 2017, the PHEOC’s review of laboratory data led to early identification of cholera in Kigoma, Dodoma, Mbeya, Rukwa, and Dar es Salaam, before it was captured by syndromic surveillance systems.

“That’s where the lab data became critical,” says Wangeci Gatei, a Health Scientist supporting lab systems in Tanzania. “Cholera cases are now being identified in the labs, complimenting IDSR and enhancing real time biosurveillance. The PHEOC is able to get the information and quickly mobilize control measures.” As of March 2018, cholera had flared across all 26 geographic regions in Tanzania and affected more than 34,000 people. But the country’s global heath security efforts are helping to stem the epidemic’s tide by creating systems that equal faster, smarter response.