Key points

- Varicella (chickenpox) is an acute infectious disease caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

- The most common chickenpox complications are bacterial infections of the skin and soft tissues in children and pneumonia in adults.

- The most effective prevention for varicella is chickenpox vaccination.

Cause

Varicella is highly caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV), which is a DNA virus that is a member of the herpesvirus group. Primary infection with VZV causes varicella. After the primary infection, VZV stays in the body (in the sensory nerve ganglia) as a latent infection. Reactivation of latent infection causes herpes zoster (shingles).

Who is at risk

People at risk for severe varicella include:

- Immunocompromised people without evidence of immunity to varicella.

- Pregnant women without evidence of immunity to varicella.

- Newborns whose mothers have varicella from 5 days before to 2 days after delivery.

- Premature babies exposed to varicella or herpes zoster.

Incubation period

The average incubation period for varicella is 14 to 16 days after exposure to a varicella or a herpes zoster rash. It takes from 10 to 21 days after exposure to the virus for someone to develop varicella.

How it spreads

The virus can be spread from person to person by direct contact, inhalation of aerosols from vesicular fluid of skin lesions of acute varicella or zoster; and possibly through infected respiratory secretions that also may be aerosolized.

A person with varicella is considered contagious beginning 1 to 2 days before rash onset until all the chickenpox lesions have crusted. Vaccinated people may develop lesions that do not crust. These people are considered contagious until no new lesions have appeared for 24 hours.

Based on studies of transmission among household members, about 90% of susceptible close contacts will get varicella after exposure to a person with disease.

Although limited data are available to assess the risk of VZV transmission from zoster, one household study1 found that the risk for VZV transmission from herpes zoster was approximately 20% of the risk for transmission from varicella.

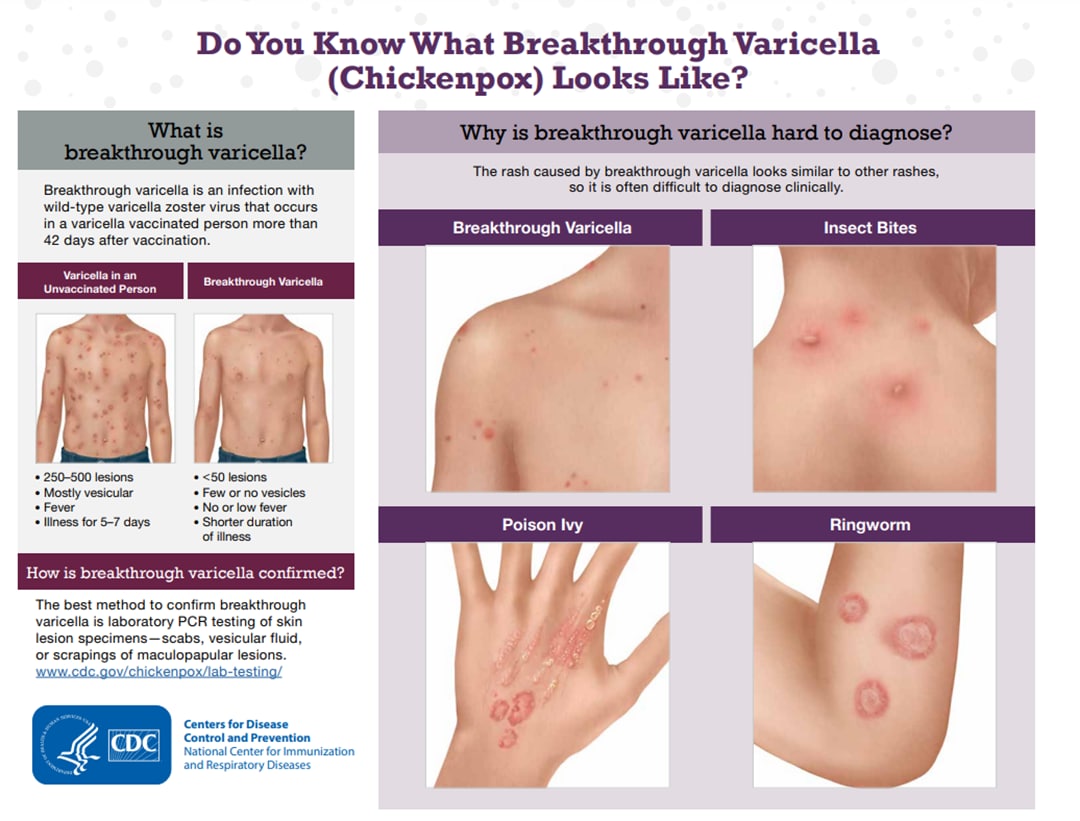

Breakthrough varicella is also contagious. One study2 of varicella transmission in household settings found that people with mild breakthrough varicella (<50 lesions), who were vaccinated with one dose of varicella vaccine, were one-third as contagious as unvaccinated people with varicella. However, people with breakthrough varicella with 50 or more lesions were just as contagious as unvaccinated people with the disease.

Disease rates

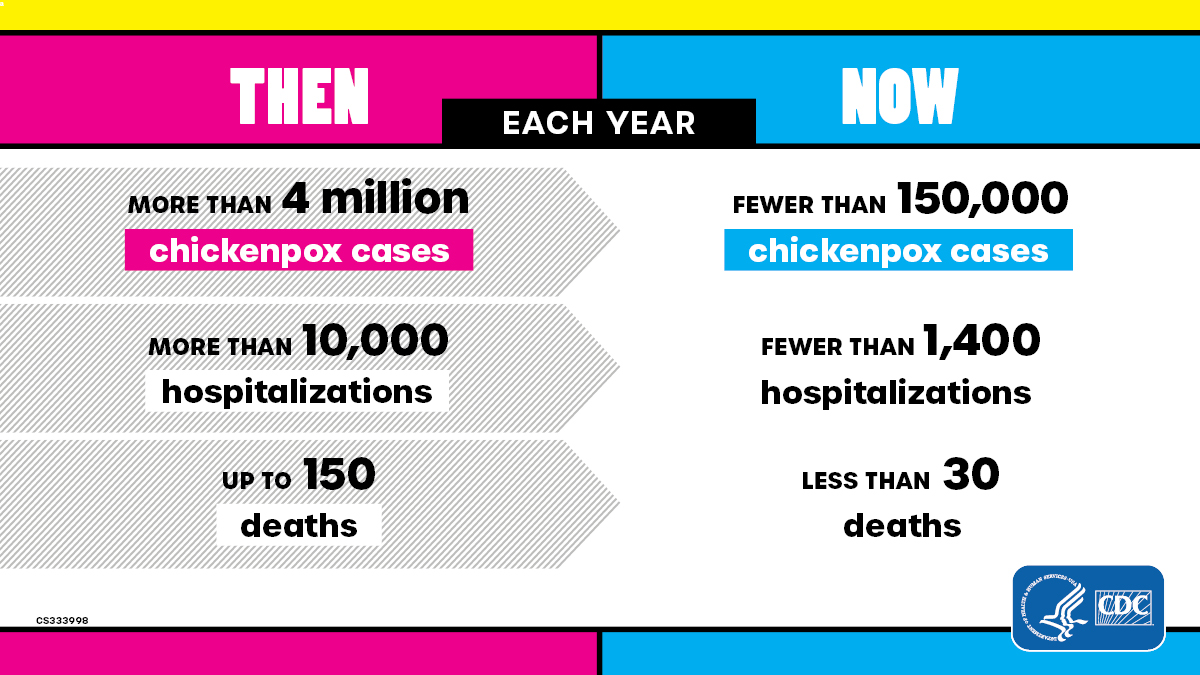

Prior to vaccine introduction:

Varicella used to be very common in the United States and contributed significantly to the burden of childhood disease. In the early 1990s each year:

- More than 4 million people got varicella

- 10,500 to 13,500 were hospitalized

- 100 to 150 died

More than 90% of cases, 70% of hospitalizations, and about half of the deaths occurred in children.

To see post-vaccine era disease rates, read about the impact of the U.S. varicella vaccination program.

Clinical features

A mild prodrome of fever and malaise may occur 1 to 2 days before rash onset, particularly in adults. In children, the rash is often the first sign of disease.

In unvaccinated people, varicella progresses rapidly from macular to papular to vesicular lesions before crusting.

The most common chickenpox complications are bacterial infections of the skin and soft tissues in children and pneumonia in adults.

Breakthrough varicella occurs less frequently among those who have received 2 doses of vaccine; compared with those who have received only 1 dose.

Prevention

CDC recommends 2 doses of varicella vaccine for all children, adolescents, and adults without evidence of immunity to varicella. Those who previously received one dose of varicella vaccine should receive their second dose for best protection against the disease.

Nosocomial transmission of VZV is well-recognized and can be life-threatening to certain groups of patients. Reports of nosocomial transmission are uncommon in the United States since the introduction of varicella vaccine.

Patients, healthcare providers, and visitors with varicella or herpes zoster can spread VZV to susceptible patients and healthcare providers in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and other healthcare settings. In healthcare settings, transmissions have been attributed to delays in the diagnosis or reporting of varicella and herpes zoster and failures to implement control measures promptly.

Although all susceptible patients in healthcare settings are at risk for severe varicella and complications, certain patients without evidence of immunity are at increased risk.

Testing and diagnosis

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) laboratory testing information applies to testing and diagnosis of primary VZV infection (varicella) and reactivation (herpes zoster). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the most helpful laboratory test for confirming cases of varicella. PCR can detect VZV DNA rapidly.

Patient management

Isolation

Healthcare providers should follow standard precautions, airborne precautions (negative air-flow rooms), and contact precautions until lesions are dry and crusted. If negative air-flow rooms are not available, patients with varicella should be isolated in closed rooms. They should have no contact with people without evidence of immunity. Patients with varicella should be cared for by staff with evidence of immunity.

Impact of U.S. varicella vaccination program

The varicella vaccination program has dramatically decreased virus circulation and increased community protection.

- Varicella hospitalizations and deaths declined 94% and 97%, respectively, among people 50 years old and younger.

- The greatest decline in cases was among people 20 years old and younger who were born during the program, with 97% drop in hospitalizations and more than 99% drop in deaths.

- The risk of shingles is significantly lower among vaccinated children, including those who are immunocompromised.

- There is about an 80% lower risk of shingles among healthy vaccinated children compared to unvaccinated children who had wild-type varicella.

Disease prevented and dollar saved

During the first 25 years, the U.S varicella vaccination program saved 118,000 life-years, at net societal savings of $23.4 billion and prevented an estimated:

- 91 million cases

- 238,000 hospitalizations

- 1.1 million hospitalization days

- 2,000 deaths

For every $1 spent, the estimated return on investment is $1.70; however, the benefits of the investment will continue to accrue beyond 2020.

- Seiler HE. A study of herpes zoster particularly in its relationship to chickenpox. Journal of Hygiene. 1949;47(3):253-262. doi:10.1017/S002217240001456X.

- Seward JF, Zhang JX, Maupin TJ, Mascola L, Jumaan AO. Contagiousness of varicella in vaccinated cases: a household contact study. JAMA. 2004 Aug 11;292(6):704-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.704. PMID: 15304467.