Wildfires in California: A Critical Use Case for Expanding State Capacity and Sharing Information Across Public Health Jurisdictions

Disaster Response, Environmental Exposure, Collaboration

In 2018, California experienced its most destructive wildfire season on record.1 More than 25 million acres of California wildlands are classified as very high or extreme fire threats—a risk area covering more than half the state.2

At the onset of the fires, California’s decentralized and independent public health jurisdictions were in various stages of becoming part of CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP). NSSP scientists contacted Sacramento, San Mateo, and other affected sites to propose technical assistance, guidance, and resources for monitoring wildfire events. Epidemiologists in Sacramento and San Mateo counties quickly adapted the wildfire-related syndrome definitions and surveillance techniques. They set up monitoring and response plans and formed data-sharing relationships across jurisdictional lines.

California’s use of syndromic data during the 2018 wildfire season formed cross-jurisdictional relationships and a desire for regional collaboration and information exchange around emerging areas of syndromic surveillance. The state’s experience demonstrated the utility, reliability, and timeliness of syndromic data for monitoring and characterizing wildfire-related health impacts. Funding from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program supports the use of syndromic surveillance in improving the nation’s public health.

Public Health Problem

In 2018, California experienced the most destructive wildfire season on record, with 7,571 fires burning nearly 1.7 million acres, over 23,300 damaged or destroyed structures, and 93 confirmed fatalities.1 The Camp Fire, which began on November 8, 2018, in east wind-driven fire-prone wildlands in Butte County, Northern California, was the deadliest wildfire in California history and sixth-deadliest U.S. wildfire to date.1 Today, more than 25 million acres of wildlands—a risk area of over half the state—are classified as a very high or extreme fire threat in California.2

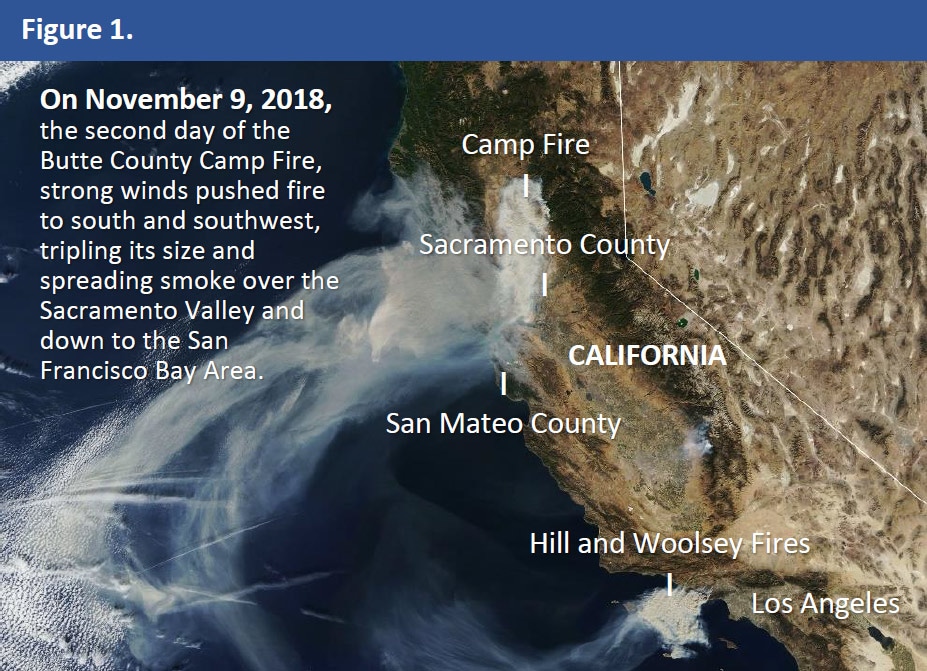

As the smoke from the Camp Fire spread south, Sacramento County, located about 88 miles downwind, observed 24-hour maximum fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations exceeding 260 μg/m3 (on day 8 of the 18-day event), with 11 consecutive days exceeding “Unhealthy” Air Quality Index (AQI) levels (24-hour average PM2.5 >65.5 μg/m3). San Mateo County, located about 200 miles downwind, experienced 7 days with concentrations exceeding “Unhealthy” AQI levels.

Figure 1. NASA Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) Worldview. Natural-color satellite image of the November 2018 Butte County Camp Fire taken by the MODIS instrument on the Terra satellite on November 15, 2018. Available from: https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/. Accessed April 4, 2019.

Actions Taken

In California, participation in the CDC National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP) is decentralized, with independently participating local health jurisdictions in various stages of planning, onboarding, and production. During the Camp Fire, CDC NSSP contacted Sacramento, San Mateo, and other affected sites to offer technical assistance, guidance, and resources. This included sharing Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-based Epidemics (ESSENCE) queries and visualizations that had been developed by Washington State Department of Health (WA DOH) epidemiologists to monitor wildfire events in their state. The support enabled Sacramento and San Mateo counties to rapidly leverage, adapt, and extend wildfire-related syndrome definitions and surveillance techniques that had demonstrated utility and value; define specific monitoring and response needs that differ based on wildfire proximity and magnitude; and establish relationships and direct lines of communication with other sites.

Sacramento County

Sacramento County Public Health used a modified version of the wildfire smoke query developed by WA DOH to monitor the number of emergency department (ED) visits related to wildfire smoke exposure. Using ESSENCE, Sacramento also monitored ED visits for other wildfire-related health and emergency response concerns using queries shared by CDC NSSP, including all respiratory syndromes, asthma or reactive airway disease (RAD), Butte County resident visits, and overall increase in ED visits, among others. Combined with air quality data (PM2.5), this information was shared with public health officials to provide situational awareness for public health messaging. In Sacramento County, the number of ED visits related to wildfire smoke exposure increased on the days where air quality was poor from wildfire smoke (Figure 2). The percent of ED visits for any respiratory-related health condition also increased with poor air quality. During this time, a higher percent of Butte County residents was also seen in Sacramento County EDs, with some mentioning the terms “Paradise” or “evac[uation].”

Lessons Learned: Strategy for Setting Up a New SyS Domain

San Mateo County Health sought advice from San Diego County Health and Human Services Agency,* an early adopter of the BioSense Platform and other SyS tools with extensive experience conducting SyS for the 20033 and 20074,5,6 San Diego wildfires. San Diego’s work served as a foundation for initial surveillance and helped inform the development of a standardized strategy for establishing a new SyS domain:

- Conduct a brief review of the literature and verify assumptions and considerations with subject matter experts and health officials.

- Define priority populations and receptors (the individuals or populations that could be adversely affected by the event) based on event-specific sensitivity, susceptibility, vulnerability, and variability.

- Select endpoints and determine whether there are existing subsyndromes or chief complaint (CC) and discharge diagnosis (DD) categories for those endpoints. If not, then define a new syndrome and develop and test custom queries.

- Validate candidate queries using the Chief Complaint Query Validation (CCQV) tool (assess the percent of probable records captured by each word in the query).

- Conduct enhanced SyS, active case finding, event-monitoring, or retrospective surveillance by using ESSENCE and other sources of complementary, contextual, or confirmatory (3C) surveillance data.

- Provide a situational report (at scheduled intervals or as needed) to officials, with notification of any sudden or sustained alert activity, clinically compatible or suspected cases, or unusual occurrences that may warrant public health investigation or response.

San Mateo County

San Mateo County public health officials were primarily interested in monitoring for acute respiratory health effects and ED surge capacity in response to sustained smoke plume days and elevated AQI levels. Since San Mateo County Health had no experience conducting SyS to monitor for health effects of wildfire smoke exposure, San Mateo County epidemiologists and informaticians consulted scientists from CDC NSSP, California Department of Public Health (CDPH) Environmental Health Investigations Branch (EHIB),† California Department of Public Health (CDPH) Climate Change and Health Equity Program (CCHEP),‡ and Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) Climate and Respiratory Health Workgroup. San Mateo County observed increases in weekly percentage of ED visits (Figure 2) for possible smoke exposure or smoke inhalation, asthma or RAD exacerbation, and other respiratory health effects associated with wildfire air pollution exposure, with the highest percentage of patients in the 0–4 years and 25–49 years age groups. Among participating EDs, the county’s safety net hospital had the highest average daily percentage of ED visits for all respiratory syndromes, excluding influenza-like illness and pneumonia. There was also a higher than expected increase in weekly percentage of ED visits for wildfire-related smoke exposure and smoke inhalation§ with mentions of “smoke” or “fires,” such as “coming in for asthma due to smoke,” “requesting inhalers due to smoke,” “follow up after smoke/fires,” and “using albuterol to help control symptoms does help but get triggered by the extra smoke.”

Figure 2: (A) Wildfire smoke-related ED visits, Sacramento County, July–December 2018; (B) All respiratory-related ED visits, Sacramento County, November–December 2018; (C) 24-hour maximum PM2.5 concentrations in San Mateo County and California wildfires, February–December 2018; (D) percentage of ED visits due to asthma or RAD in San Mateo County during the October 2017 Northern California Wildfires and 2018 Camp Fire, February–December 2018.

† Sumi Hoshiko, Research Scientist, Environmental Health Investigations Branch, California Department of Public Health

‡ Jason Vargo, Lead Research Scientist; Meredith Milet, Epidemiologist; Climate Change and Health Equity Program, California Department of Public Health

§ Mentions of wildfire-related smoke exposure and smoke inhalation were queried using the following ICD-10-CM codes and terms: X01, exposure to uncontrolled fire, not in building or structure (includes exposure to forest fire); T59.811, toxic effect of smoke, accidental (unintentional); J70.5, respiratory conditions due to smoke inhalation

Outcome

Figure 3. California participation in CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP) by county, May 2019.

To continue building on the capabilities developed during the Camp Fire, San Mateo County responded to a CSTE call for proposals to develop a climatic exposures and respiratory health outcomes pilot. The proposal was selected for funding, along with proposals from the WA DOH and Propeller Health. With CSTE support, San Mateo County initiated development of a wildfire and respiratory health software application for public health officials, which will include a suite of tools for near real-time situational awareness and data-driven decision making. The application includes a vulnerability index builder; a SyS dashboard; data streams dashboard powered by ArcGIS, ESSENCE, Google BigQuery, Data Studio, and R Shiny; and a wildfires and health surveillance resource repository.

The cross-jurisdictional relationships that were formed during the Camp Fire, the recent CDC NSSP/CSTE Data Sharing Workshop Series, and desire for regional collaboration and information exchange around emerging areas of SyS reignited efforts to establish a California-wide BioSense Platform user group, which was formed in July 2019 with several CDPH partners and membership from Nevada, Riverside, Sacramento, San Diego, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, and Yolo counties. To date, the group has held two statewide calls to discuss regional data and resource sharing and has developed a survey of SyS capabilities and BioSense Platform participation that will be distributed statewide to local public health agencies to assess the current state of SyS in California.

References

1. California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. Incidents [Internet]. Sacramento (CA): California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. 2018 Incident Archive [cited 2019 Sept 19]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2018/

2. California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. Community wildfire prevention and mitigation report: In response to Executive Order N-05-19 [Internet]. Sacramento (CA): California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, 2019 Feb. Executive summary; p. 2. Available from: https://www.fire.ca.gov/media/5584/45-day-report-final.pdf

3. Johnson JM, Hick L, McClean C, Ginsberg M. Leveraging syndromic surveillance during the San Diego wildfires, 2003. MMWR [Internet]. 2005 Aug [cited 2019 Sept 19];54(Suppl):190. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su5401a36.htm

4. Ginsberg M, Johnson J, Tokars J, Martin C, English R, Rainisch G, Lei W, Hicks P, Burkholder J, Miller M, Crosby K, Akaka K. Monitoring health effects of wildfires using the BioSense system – San Diego County, California, October 2007. MMWR [Internet]. 2008 Jul [cited 2019 Sept 19];57(27):741-747. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5727a2.htm

5. Hutchinson JA, Vargo J, Milet M, French NHF, Billmire M, Johnson J, Hoshiko S. The San Diego 2007 wildfires and Medi-Cal emergency department presentations, inpatient hospitalizations, and outpatient visits: An observational study of smoke exposure periods and a bidirectional case-crossover analysis. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2018 Jul [cited 2019 Sept 19];15(7):e1002601. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002601

6. Thelen B, French NHF, Koziol BW, Billmire M, Owen RC, Johnson J, Ginsberg M, Loboda T, Wu S. Modeling acute respiratory illness during the 2007 San Diego wildland fires using a coupled emissions-transport system and generalized additive modeling. Environ Health [Internet]. 2019 Nov [cited 2019 Sept 19];12:94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-12-94

Lessons Learned

California’s use of syndromic data during the 2018 wildfire season helped launch syndromic surveillance (SyS) capacity-building initiatives among local public health agencies to—

- Demonstrate the utility, reliability, and timeliness of syndromic data for monitoring and characterizing wildfire-related health impacts;

- Establish channels for cross-jurisdictional communication, collaboration, resource exchange, and technical assistance;

- Explore regional data sharing and integration opportunities;

- Increase participation and engagement in professional workgroups and communities of practice focused on SyS, applied public health informatics, and data science;

- Develop partnerships with academic institutions, technology companies, and other governmental agencies with subject matter expertise in wildfire-related SyS and air quality monitoring;

- Design workflows to integrate multiple information sources;

- Develop standard messages for communicating SyS use cases, applications, benefits, and limitations to public health, health care, and emergency response authorities; and

- Expand wildfire-related SyS preparedness capabilities to include surveillance during Public Safety Power Shutoff events.

Contacts

San Mateo County Health

Epidemiology Unit

Office of Public Health Data, Surveillance, and Technology

Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance

www.cdc.gov/nssp

This success story shows how NSSP

- Improves Data Representativeness

- Improves Data Quality, Timeliness, and Use

- Strengthens Syndromic Surveillance Practice

- Informs Public Health Action or Response

The findings and outcomes described in this syndromic success story are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Syndromic Surveillance Program or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.